Cover Story

Jeffrey Joe Morin: A Big Ol’ Heart

Jeffrey Joe Morin. Photo by Steve Covault

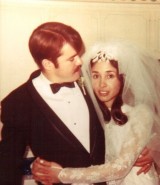

Jeffrey Joe and Andi on their wedding day.

Jeffrey Joe with Veronica May of the Forget Me Nots

Photo by Dennis Andersen

“You’re going to make a record with me!” These were the words that Jeffrey Joe Morin heard coming from a very enthusiastic and determined Steph Johnson when he was performing with his band the Forget Me Nots last year. Johnson, of course, is San Diego’s brilliant and beautiful soul and jazz singer, distinguished by her award winning recordings and busy performance schedule, the Steph Johnson who was on the cover of last month’s Troubadour.

On the other hand, Morin has won no music awards and has never made a recording of his own. Though he has played music for most of his life, for years Morin and his guitar have been found more often at small jams or friendly gatherings than on stages or music festivals. Johnson’s enthusiasm for Morin and his music, however, is not all that surprising. In the last few years this self-taught musician has received a great deal of attention and accolades from San Diego’s music community, and some of this town’s most prominent musicians, such as Joe Rathburn and Gregory Page (see sidebar), sing his praises as a performer and songwriter.

Morin would most readily be described as a balladeer, favoring the gems of the Great American Songbook. At any of his performances you’re likely to hear the songs of Hank Williams, Rodgers and Hart, Marty Robbins, and Cole Porter. He sings the hits of Broadway as well as the musical favorites that have spilled out of all the juke joints and honkytonks of this country’s back roads and byways. A tenor, Morin never seems to put much effort into singing. The lyrics and melody seem to flow from him very easily. Surprisingly, even when he doesn’t have a microphone and his guitar isn’t amplified, as it is for some house concerts and smaller performance venues, both his voice and guitar have a great deal of presence and fill a room without any trouble.

It doesn’t matter who is singing or what is being sung — though it probably helps if it is an old country or jazz standard — Morin can join in harmony almost instinctively. “It’s just second nature to me,” he says. “I have that knack. It can be two or three people singing; I can come along and find that third note. I can find that fourth note,” he says. He learned harmony as a child when he was trotted off to church. “I got everything I know about harmony from the Lutheran hymnal. The hymnal was so simply laid out it was like shape note singing. I could tell where I needed to be to sing.”

A large man — some folks say that he reminds them of a big teddy bear — Morin speaks slowly, clearly, and softly, like a person who has spent his life teaching small children. As he speaks, his arms don’t move much. If he has his guitar with him, his hands never stray far from the strings or neck of the instrument. Being a player and a picker for over 50 years, Morin looks exceptionally comfortable with an acoustic strapped over his shoulder. Whether he is sitting or standing, he seems to cradle his dreadnought in his arms. He strums sometimes but for the most part he fingerpicks while his left hand goes up and down the fingerboard to find those minor ninth and augmented sixth chords of the jazz standards in his repertoire.

Besides singing and playing guitar, Morin blows a pretty mean harp. His harmonica work can be found on a couple of Joe Rathburn CDs, and Morin just recently completed some recording for Beston Barnett for one of Barnett’s Art Hurts recordings. “It was one take!” he says, revealing the surprise he finds in the very short recording session. Like the guitar, the harmonica has been with Morin most of his life. “My father had a harmonica. I remember he used to play “Isle of Capri.” I fiddled with it sometimes. When I was in the Navy in San Francisco, I bought one, a Hohner Marine Band. I just played it until I got good at it. Anymore I think I’ve gotten pretty damn good at it, too.”

Morin conveys a great deal of emotion in his performances. Particularly on the soulful ballads or old-fashioned torch songs that he favors, his brow furrows and a crack comes across in his voice when he reaches the heartbreaking bridge or chorus. Steeped in jazz traditions, he often sings behind the beat, way behind the beat, sometimes stretching a phase into the next measure.

Johnson followed through with her promise of recording with Morin. With the working title of Big Ol’ Heart, the two have been in the studio adjusting microphones, pushing buttons, and laying down tracks for several months, with the plan of releasing the recording sometime this fall. The story goes that Morin was already set to make a recording with another San Diego musician, but that project fell through when Morin’s musical partner left town. Always the balladeer of standards and classics, the CD project is prompting Morin to write tunes of his own. Until recently he had only written two songs: “Without Your Love to Hold Me Back,” a sweet and ironic love song, and “Big Red Lips,” another love song, but one that is bluesy and pretty gosh darn funny.

“For me it has always been about he guitar. Guitar playing came easy to me,” Morin says. “I actually don’t like writing songs. Writing a song is like construction for me. I get going and I find that I have too many ideas. Computers have made it easy. I do a lot of cutting and pasting when I’m working on a song.” Morin estimates that he has written up to eight songs for the recording project. Along with Johnson, he is working with the multi-instrumentalist powerhouse Leo Dombecki to record and produce the CD. Besides the songs he is writing, a recent financial windfall has allowed Morin to buy the rights to four or five standards, such as “Stardust,” which he plans to include on the disk.

“My mom threw my father’s guitar in the street.” Morin says, laughing at the memory. “He came home with a guitar instead of a paycheck,” he continues. Despite this introduction to impulse buying and family discord, Morin wound up with a guitar of his own, shelling out three dollars for his first acoustic when he was a child. “From the first time when I was 11 or 12 years old I could play from what I’d seen other people do, how to form chords, and all that. I didn’t have to think about it. The more I watched, the more I learned,” he says. In 1959 Morin bought a Harmony guitar, one of their sturdy Sovereign models, on a trip to a pawnshop in the seedier end of Stockton. The purchase set him back $12 (equal to about $93 today).

As far as being a bluesman or balladeer, Morin started out in life with an advantage. His parents had a record collection that exposed him to a wide variety of music. “My father was a blues and rockabilly fan. He had a pretty strange record collection, at least for a white guy,” he says. “My dad had a Coleman Hawkins record and I remember listening to Hawkins play and thinking that he was singing through the saxophone. Mom listened to orchestral music. She had 33s and 16s of Tchaikovsky and other classical music.” This musical cornucopia that his parents provided to their son left an impression on him and helped him develop his catholic musical tastes. Morin is just as comfortable talking about his love of Django Reinhardt and the Hot Club of Paris as he is showing his appreciation for Arthur Rubenstein or even Merle Haggard, for that matter.

Though he is of the baby boomer generation, the age group that venerated singer/ songwriters as though they were rock stars, Morin was never drawn to the Subterranean Homesick Fire and Rain type of music. He likes the old-time standards. For inspiration he also draws on the singers who sang those songs from way back when, mostly the female singers like Jo Stafford, Dinah Shore, Doris Day, and Pearl Bailey. For the fellahs who influenced him Morin names Johnny Mercer, Dean Martin, and Hoagy Carmichael. He admires Martin for the Rat Packer’s vocal strength, and “everything that Carmichael sang seemed so effortless,” he says.

As his father was a career Navy man, Morin is one of those military brats who comes from everywhere, having grown up in California, Minnesota, and a few other spots on the map. He even spent some time as a child on the tiny island of Guam. By the time he was hitting junior high and high school age, the family was in the San Diego area, settling in Imperial Beach. Morin began performing in high school when he joined his first rock band, Cathy and the Casuals. The band played music for high school dances and a few other events. Morin loved music, but at the time was plagued by stage fright, a musical handicap that would continue to plague him for years. He played rhythm guitar rather than putting himself in the spotlight of being a lead guitarist.

Soon after his time with Cathy and the Casuals, as the exotica and Pacific islands craze swept across the country, sprouting the tiki bars that served up those very sweet alcoholic drinks, adorned with those cute little umbrellas, Morin donned a Hawaiian shirt and played ukulele with Pete Auclaire and his Polynesian Serenaders. “We had a ten-woman dance troupe!” he says, recalling the grass skirt-clad hula-dancing unit. The ensemble performed around the San Diego area, which also included a broadcast from a television station south of the border in the wee hours of the night.

After high school Morin was drafted into the Army. Because his father was in the Navy, he made a few phone calls and got his son into that branch of the service. After flunking out of electronics school in San Francisco, Morin was assigned to be a deckhand in the San Francisco Bay. He later worked out of Hunter’s Point Naval Shipyard as a craft master for tugboats. Since this was in the middle of the sixties, the Navy shipped Morin off to Vietnam, where he was stationed on the Cua Dai River, 40 miles south of Da Nang. He describes his wartime tasks as “sinking boats and getting shot at.”

In the seventies Morin found himself playing Dobro with sometimes health food advocate, sometimes Merry Prankster, and full-time wild man Gypsy Boots. He says, “I worked for this fellow doing architectural drawing. His name was Vince. At the time I was in a bluegrass band, and we mostly played pizza parlors. One day Vince says to me, ‘We’re going out to the cowboy ranch.’” The cowboy ranch was an orphanage where Morin’s friend grew up. Every year this friend, Vince, sponsored a benefit for the ranch. “I remember there were clowns and circus acts. It was a big production. Gypsy Boots was there. He was also somehow connected to the NFL, and each year he would show up at the ranch with 100 footballs. I remember watching him. He could throw a football a hundred yards!” Morin hooked up with Gypsy Boots and joined Boots’ band. Morin and his new bandmates convinced Boots to change the name of the band from Gypsy Boots and the Hairy Hoots to Sherwin Williams and the Chemtones. As he recalls his time with the counterculture icon, Morin says, “The guy never turned off,” as he launches into an imitation of Gypsy Boots. Morin’s eyes grow big and his hands shake like Soupy Sales in the depths of a Benzedrine rush.

Morin deliberately decided not to choose music as a career. “I looked at people doing it and I thought ‘how can they sing the same song the rest of their lives?’” he says. “And so many of these people wind up with next to nothing after spending years playing music.” For his day gigs, he has held several positions, including skippering a tugboat in the San Francisco Bay. Earning a degree from CalArts in design, Morin has has had experience colrizing old black and white movies and has been an art director and a technical illustrator in the aerospace industry. Fat City, the steakhouse down by the San Diego waterfront, which historians are currently trying to preserve, Morin designed the interior neon lights for the restaurant. These days he works as a mechanical designer in what he says is the “coolest job of all,” though he jokingly describes his position as a designer of gizmos; he conceives of and draws up the plans for robots that are the workforce handling biological samples. These miniature R2D2s work and run their errands in super-cooled refrigerators that are kept in at minus 112 degrees Fahrenheit.

Jeffrey Joe Morin is married to a beautiful woman. Her name is Andi, and they met when Morin was in the Navy. He says, “I was living with these other sailors in San Francisco. Four coeds at San Francisco State lived downstairs. One of them was Andi. We met in the elevator a few times and saw each other around the building. One day I was home on the back stairs and she was home on the back stairs, too. We walked to the beach together. I think our first real date was going to a W.C. Fields film festival at a theater in San Francisco that showed silent films.” Morin and his wife have two grown children, a son and a daughter.

Though he has performed solo or in a number of bands, performing as opposed to simply playing music has not been the prime focus of his life. Anyone who has plucked a guitar or banjo and sat in on a jam or a song circle in San Diego has probably swapped songs or jammed with Morin. For years, in the early seventies, he was a regular at the weekly jam at Candelas, the Los Angeles music shop, famous for its fine classical guitars. “We might have everybody there, or it might be just me and another guitar player, but it was me and the same five guys every Wednesday for the better part of ten years,” he says.

After the years spent singing at home or in friends’ kitchens, Morin says that he made a very deliberate decision about 20 years ago to go out and perform. “I had to make a conscious decision to go out and play. I get really bad stage fright. I sweat and stammer and I needed to not be that way,” he says. “I can sit around in the kitchen on my own or with a few other people and I play; that’s no problem. But a roomful of people, Jeez!”

He had been playing music at Java Joes, the coffeehouse that was instrumental in launching the careers of Steve Poltz and Jewel Kilcher, when the original Java Joe’s was located in a Poway strip mall. “When Java Joe’s moved to Ocean Beach, a lot of the musicians who had been playing there gravitated over to Mikey’s. After I’d played there a few times, Mikey asked me to play Wednesday nights there,” he says. Many a Wednesday night saw Morin playing to three teenagers and six cups of coffee, but he persisted with the gig for about a year. “I wanted to keep doing it for the people who would show up for me. I wanted to keep doing it for the people who liked me,” he says.

Mikey’s in Poway lasted several years. When it closed, much of the folk music singer/songwriter action shifted to the Golden Goose, a coffeehouse in the old town section of Lakeside. The move turned out to be another creative turning point for Morin. “The Golden Goose is where I met John Bosley. It was John who told me that I needed to start writing songs,” Morin says. “I showed him what I had of my first song, ‘Without Your Love to Hold Me Back.’ He touched it up a little, and it was helpful to me by showing me how to better write a song.” Bosley and Morin started performing together and were soon joined by bassist Jack Johnson. The trio performed extensively throughout San Diego as Johnson, Bosley, and Morin or under the more text message friendly name JoBozMo.

For the past year or so Morin has performed with the Forget Me Nots, As Morin tells it, the inception of the Forget Me Nots goes back a couple of years ago. Local singer/songwriter Lindsay White’s grandparents had met over a National Steel guitar. When they passed away recently, White inherited the guitar. “With this guitar, no matter what they did, the only kind of music that came out of it was 1930s music,” Morin says. “So Lindsay and her musical partner, Veronica May, started writing songs in the 1930s style.” The band added San Diego’s soulful singer/songwriter Allegra Barley and Allegra’s father, Mr. Barley, as well as Kristine Vandenberg. Morin says, “They hooked up with me because when you think of old songs you think of Jeffrey Joe.” No longer a performing unit, the sextet played frequently at Catherine Beeks’ San Diego Acoustic Alliance.

As he has worked to overcome his natural stage fright, Jeffrey Joe Morin is now performing and receiving the recognition as a musician that has eluded him for decades. Be they the old songs of the American Songbook or the news songs that he is writing, be it a solo performance or singing harmony in a trio or quartet, he plans to keep performing for his audiences. “It’s pretty simple what I do,” he says. “Give the people who like me what they want.”