Yesterday And Today

I’d Love to Turn You On: A Brief History of Psychedelics

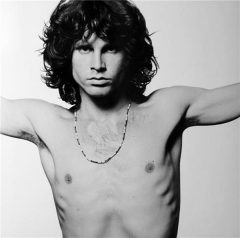

There’s the known. And there’s the unknown. And what separates the two is the door. And that’s what I want to be. I want to be the door.

– Jim Morrison (1943—1971)

And the lonely voice of youth cries: What is truth?

– Johnny Cash (1932—2003)

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.

– William Blake (1757—1827)

I get high with a little help from my friends.

– John Lennon (1940—1980) & Paul McCartney (1942—)

Call it whatever you like: the Summer of Love, the Summer of Discontent, or the Vietnam Summer. But no matter which way the nomenclature billows in the breeze, it is impossible to have a substantive understanding regarding the events of 1967 without exploring the significant impact that drugs had on world culture, in particular, psychotropic drugs.

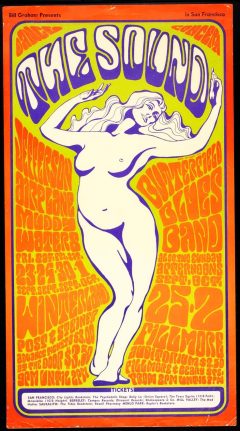

Whether sober or intoxicated, to take a gander at the surreal, graphically undulating handbills and posters of the late 1960s, and interpret the amorphous blobs of text (announcing the next series of musical performances at the Fillmore and Avalon ballrooms in San Francisco) is to be immersed in psychedelic culture. And to swim upstream within the electric Kool-Aid current of Stanley Mouse or Rick Griffin’s mystical calligraphy and extract meaning from its perpetual motion requires a special pair of shamanistic goggles: i.e., adopting the role of a fellow visionary.

To move from the romantic existentialism of William Blake to the lysergic musings of Allen Ginsberg, James Douglas Morrison, Robyn Hitchcock, and Julian Cope is to understand that psychedelia neither began nor ceased in the 1960s. In fact, humankind has been exploring altered states of consciousness for longer than we can remember, with mystics, healers, and poets throughout the ages embodying what the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia proclaimed after his first LSD experience: “I knew there was more going on than what they were telling me!”

To explore the nature of consciousness is one of the trickiest, significant, and sublime meditations we can partake in as human animals. What exactly did George Bernard Shaw mean by his statement: “Thought transcends matter?” Subatomic physics and the laws of thermodynamics state that all matter is a form of energy. And, according to the law of conservation, energy can neither be created nor destroyed. Energy may change form, and energy can certainly flow from one place to another. We can harness it, store it, regulate it, control it, and direct it, but much like consciousness itself, we still don’t know what energy is. The psychedelic experience is analogous to a Zen koan: an enigma wrapped in a riddle. That’s just one of life’s mysteries that we’re still seeking to unravel.

****************

You can thank the mass media for many things over the long course of our evolution, but there wouldn’t be a “Summer of Love” without Life magazine, et al., heavily promoting such hype in the first place. Similarly, we can also thank the mass media for the perception–or, rather, the skewed perception–of how psychotropic substances impact human consciousness. The difference between education and propaganda can veer between subtle and extreme, and is typically predicated upon what your particular political agenda happens to be. When it comes to the politics of the two most influential alphabet agencies within the United States government–the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)–power and control have long been the name of the odious game that these rogue factions deal in.

Controlling the black magic money markets of international finance and the overall torrent of information that reaches the general public are just two of the myriad ways that the dark forces of these agencies act against the well being of the world’s population. And the overall fear porn that the mass media promotes in the name of “news and information” continues as an absurd farce that only the most discerning can see through for what it is: at best, a parade of trivial characters and events to distract us, and at worst, a disinformation campaign in order to propagate lies to support a murderous system of greedy exploitation. In addition to raping and pillaging the natural resources of our planet, the end result of said exploitation is that the man and woman on the street is literally and emotionally taxed with supporting nefarious black budget operations and endless wars around the globe allowed by our ignorance and/or willful bigotry. This supports a despicable value system that allows such elitist campaigns to occur under the farcical banners of “freedom,” “liberation,” and “democracy.” It’s a joke as stale as Henny Youngman yammering, “Take my wife, please.”

If information is power, and indeed it is, those who control the flow of information are positioned to hold dominion over the unenlightened. Ignorance is the worst form of Achilles Heel, and the only antidote to being vulnerable to the propaganda of psychopaths is to wake up and become educated. That requires questioning every single idea that is perpetuated in our public discourse, with critical, rational, and analytic thought.

Nowhere is this more important than in discerning how and where our perception of what constitutes “reality” comes from. Our mass media is really an industry of fascism that attempts to singularly define your reality for you. And the wonderful thing about free will is that you can choose to hand your power over to outside agencies and blindly be led by the nose to wherever your masters choose to take you, or you can be the captain of your own ship and steer the course of your life’s path based upon the experiential wisdom of knowing your true place in this world. And to know your true place in the world requires the fundamental understanding of how we all create this collective reality, based upon what we choose to integrate into our consciousness and what we choose to project outwardly into the multiverse. Or, as Bob Dylan said in 1963: “You can be in my dream if I can be in your dream.”

****************

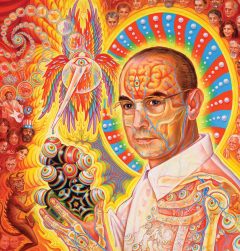

On November 16, 1938, a 32-year-old chemist named Albert Hofmann first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) while investigating the chemical and pharmacological properties of ergot, a rye fungus rich in medicinal alkaloids, for Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland. Hofmann set the compound aside for five years, until April 16, 1943, when he had “a peculiar presentiment” that it would be “worthwhile to carry out more profound studies.” While re-synthesizing a new batch of LSD, he accidentally absorbed a small dose through his fingertips and experienced a “remarkable, but not unpleasant, state of intoxication…characterized by an intense stimulation of the imagination and an altered state of awareness of the world.

“As I lay in a dazed condition with eyes closed, there surged up from me a succession of fantastic, rapidly changing imagery of a striking reality and depth, alternating with a vivid, kaleidoscopic play of colors. This condition gradually passed off after about three hours.”

Intrigued by the experience, Hofmann intentionally ingested what he believed to be a miniscule amount (250 micrograms) of LSD three days later, on April 19, 1943. Less than an hour later, Hofmann experienced sudden and intense changes in perception. He asked his laboratory assistant to escort him home and, as use of motor vehicles was prohibited because of wartime restrictions, they made the journey on bicycles. “I had great difficulty in speaking coherently,” he later recalled. “My field of vision swayed before me and objects appeared distorted like curved mirrors. I had the impression of being unable to move from the spot, although my assistant told me afterwards that we had cycled at a good pace.”

Hofmann’s condition rapidly deteriorated as he struggled with feelings of anxiety, alternating in his beliefs that his next-door neighbor was a malevolent witch, that he was going insane, and that the LSD had poisoned him. For a while he feared that he was losing his mind. “Occasionally I felt as if I were out of my body. I thought I had died. My ‘ego’ was suspended somewhere in space and I saw my body lying dead on the sofa.”

Eventually Hofmann’s mood shifted, and he was able to explore the hallucinations in a state of relative calm, enjoying the synesthetic effects of seeing sound and hearing visuals until he fell into a fitful sleep. The next morning he awoke feeling perfectly fine. In fact, he was more than fine–he had a heightened sense of his environment and a deeper appreciation for sights, sounds, and smells. Hofmann had successfully navigated the world’s first acid trip.

****************

Although Albert Hofmann didn’t understand it at the time, LSD had opened a Pandora’s Box into the unconscious of the human mind, the Universal Mind–what some might refer to as a Jungian archive of archetypes containing the knowledge of all antiquity. After filing a report of his experiment with his superiors at Sandoz, they pondered the commercial applications of this new compound. As LSD is similar in its structure and effects to mescaline, Sandoz began marketing the drug in 1949 to the psychiatric community, believing LSD (like mescaline) to be a mimicker of psychoses in mental patients. Sandoz believed it had two potential purposes: 1) “Analytical–to elicit release of repressed materials and provide mental relaxation, particularly in anxiety states and obsessional neuroses;” and 2) “Experimental–by taking LSD himself, the psychiatrist is able to gain insight into the world of ideas and sensations of mental patients. It can also be used to induct model psychoses of short duration in more normal subjects, thus facilitating studies on the pathogenesis of mental illness.”

Regardless of the usefulness and/or potential harm to be found in Freudian psychoanalysis, (for more on that subject you are referred to We’ve Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World’s Getting Worse by James Hillman and Michael Ventura)–leave it to the CIA to take LSD and experiment with its use in interrogations and torture, in order to learn how to control and program the mind and destroy the will of a subject.

The secret, black budget operations that the CIA has engaged in since its charter in 1947 are voluminous, and few are more odious that the CIA’s mind control program MK-Ultra. Officially sanctioned in 1953 and allegedly halted in 1973, MK-Ultra has become synonymous with the ideas in Richard Condon’s 1959 political thriller novel The Manchurian Candidate, where mind control and brainwashing can be used to create unwitting political assassins and super soldiers. Through the Freedom of Information Act, the depths of the CIA’s chicanery were eventually exposed in Martin A. Lee’s and Bruce Shlain’s Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. The MK-Ultra program used numerous methodologies to manipulate brain activity and mental faculties, including the surreptitious administration of drugs (especially LSD), hypnosis, sensory deprivation, isolation, and verbal and physical abuse, as well as other forms of psychological torture. The scope of the MK-Ultra project was enormous, with research undertaken at 80 institutions, including the participation of 44 colleges and universities, as well as hospitals, prisons, and pharmaceutical companies.

To study the history of the 20th century is to understand the infinite array of techniques by which the human psyche can be terrorized, imprinted, and radicalized. In 1945, prior to the advent of MK-Ultra, the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency was established and given direct responsibility for Operation Paperclip, where more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians, many of whom had leadership roles in the Nazi Party, were recruited and brought to the United States to gain a military advantage in the burgeoning Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Several other secret U.S. government projects grew out of Operation Paperclip, including Project CHATTER, and Project BLUEBIRD. But none were more significant in terms of international espionage and terrorism against domestic dissidents than MK-Ultra.

****************

Inevitably, there were a significant number of casualties strewn along the path of the government’s reckless and sadistic experimentation in its quest for an interrogative truth serum, but the deepest irony to the CIA’s attempts at mastering the art of mind control is that it inadvertently turned some of its test subjects into full-blown bohemian seers–cultural renegades who managed to spark a variety of social revolutions throughout America and abroad. Apparently, blowback is an unintentional bitch.

Some of the most famous figures of the 1960s are notorious specifically because of their involvement with psychedelic drugs. And nearly every single one of them has managed to be linked in some fashion with the CIA, the FBI, or in Aldous Huxley’s case, the British Intelligence agency MI6. In The Doors of Perception, Huxley’s slim volume from 1954 about his experiences with mescaline, he breathlessly proclaimed that the psychedelic vision was “how one ought to see.” The Doors of Perception, and its follow-up essay, Heaven and Hell, aroused a generation of truth seekers, including the Doors’ Jim Morrison, rock’s premier acid poet, who was subsequently inspired to use Blake’s quotation as the moniker for his quartet of renegades. Without LSD, there would be no protagonist canceling his subscription to the resurrection, or imploring you to take a chance, and break on through to the other side. The first two Doors LPs are unparalleled masterpieces, and they owe much their innovative mastery and mystery to the wonders of psychedelic drugs.

But nine years before Jim Morrison got his hands on a vial of LSD and spent the summer of ’66 tripping on a Venice, California rooftop, there were the CIA-sponsored experiments going on up north at Stanford University where an aspiring young writer named Ken Kesey was being given psilocybin, LSD, the superamphetamine IT-290, and Ditran in a clinical setting–it was turning his latent literary aspirations into artistic gold. After being psychedelicized, the boy wonder of Perry Lane used his newly imparted visions to crank out his meditation on the human condition. And he called his stab at the great American novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. It became a critical success and a New York Times bestseller, and Kesey dove-tailed its financial and cultural cachet into a countercultural movement that set America reeling. Thanks to the CIA’s drug program, and the generosity of several underground chemists in the Bay Area, particularly Augustus Owsley Stanley III, we wouldn’t have had Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, the Trips Festival, the Acid Tests, or the Grateful Dead. (Speaking of the Grateful Dead, lyricist Robert Hunter was also a part of the same Stanford drug experiment as Kesey.) You can also attach the gonzo journalism of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, and the all-dressed-up-but-nowhere-to-kill Hell’s Angels to the list of those culturally impacted by Kesey’s absurd, superhero scene of lysergic derangement. Fellow chemists Tim Scully and Nicholas Sand are also essential to the overall arc of the psychedelic Sixties (as documented in the film The Sunshine Makers), and thankfully, much of Kesey’s attempts to reach FURTHER are captured for posterity in the prim prose of novelist Tom Wolfe in the indispensable Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. You’re either on the bus or you’re off, and if you want to find out how weird the Sixties could get, this is a mandatory excursion that must be experienced.

****************

On May 13, 1957, Life magazine published an article by R. Gordon Wasson that documented the use of psilocybin mushrooms in the religious rites of the indigenous Mazatec people of Mexico. Wasson’s article ignited a curiosity about psychotropic substances throughout America, which included Dr. Timothy Leary, a professor of psychology at Harvard University. In August of 1960, Leary traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico, and consumed psilocybin mushrooms for the first time. Leary later wrote that he “learned more about his brain and its possibilities [and] more about psychology in the five hours after taking these mushrooms than in the preceding 15 years of studying and doing research in psychology.” Leary returned to Harvard in the fall of 1960, and along with his associate Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass), began a series of cutting edge research programs, including the Harvard Psilocybin Project, and the Concord Prison Experiment, where Leary successfully used psilocybin as a means of transforming the consciousness of violent, long-term, repeat offenders. This, of course, was before October of 1966, when LSD and psilocybin were still legal in the U.S. Eventually, Leary and Alpert were fired from Harvard over the controversy that the pair’s methodology was causing: largely due to Leary’s proselytizing and a laissez faire attitude about following Harvard’s strict academic protocols. After his dismissal, Leary reinvented himself as a “stand-up philosopher,” touring college campuses throughout the U.S. to become the most famous figure of the 1960s associated with the promotion and ingestion of LSD as a spiritual sacrament. He was immortalized in the Moody Blues song “Legend of a Mind,” but his repeated insistence that everyone who was within earshot “turn on, tune in, and drop out” inspired Richard Nixon to describe him as “the most dangerous man in America.”

To the status quo of capitalist consumption, Leary was indeed dangerous, and more than a little bit reckless, but his true danger lie at how much influence he was wielding within the therapeutic, scientific, and artistic communities. There are some who think that Leary was just another shill for the CIA, and promoting drugs as a means of disabling and taking down the Marxist radicals of the New Left. But the fact remains that the very nature of perception was shifting among a great many people due to Leary’s message, and it called into question the mechanics how we create the world around us. From Lee and Shalin’s Acid Dreams: “The notion that LSD could be used to treat psychological problems seemed downright absurd to certain scientists in light of the drug’s long-standing identification with the simulation of mental illness. Those who operated within the psychotomimetic framework did not recognize that extra-pharmacological variables–inadequate preparation, negative expectations, poorly managed sessions–were responsible for the adverse effects mistakenly attributed to the specific action of the drug. (According to the model psychosis scenario, there was really nothing to manage; just dose them and take the reaction.) They were appalled to learn that some psychotherapists were actually taking LSD with their patients. This was strictly taboo to the behaviorist, who refused to experiment on himself on the grounds that it would impair his ability to remain completely objective.

“The chasm between the two schools of thought was not due to a communications breakdown or a lack of familiarity with the drug. The different methodologies were rooted in conflicting ideological frameworks. Behaviorism was still anchored in the materialist worldview formalized by Newton; the psychedelic evidence was congruent with the revolutionary implications of relativity theory and quantum mechanics. The belief in scientific objectivity had been shaken in 1927 when physicist Werner Heisenberg enunciated the ‘uncertainly principle,’ which held that in subatomic physics the observer inevitably influenced the movement of the particles being observed. LSD research, and many other types of studies, suggested that an uncertainly principle of sorts was operative in psychology as well, in that the results were conditioned by the investigator’s preconceptions. The ‘pure’ observer was an illusion, and those who thought they could conduct an experiment without ‘contaminating’ the results were deceiving themselves.”

In 1964, Leary coauthored a book with Alpert and Ralph Metzner called The Psychedelic Experience. Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, it was a manual intended to assist novice trippers with the predictable challenges of navigating “The Other World.”

A psychedelic experience is a journey to new realms of consciousness. The scope and content of the experience is limitless, but its characteristic features are the transcendence of verbal concepts, of spacetime dimensions, and of the ego or identity. Such experiences of enlarged consciousness can occur in a variety of ways: sensory deprivation, yoga exercises, disciplined meditation, religious or aesthetic ecstasies, or spontaneously. Most recently they have become available to anyone through the ingestion of psychedelic drugs such as LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, DMT, etc. Of course, the drug does not produce the transcendent experience. It merely acts as a chemical key–it opens the mind, frees the nervous system of its ordinary patterns and structures.

The Psychedelic Experience was a boon amongst those who were seeking to ground the LSD experience into a systematic methodology, and perhaps the most important acid freak to take heed of Leary, Alpert and Metzner’s cosmology was head Beatle John Lennon, who took their instructions and channeled them verbatim into the psychedelic masterstroke, “Tomorrow Never Knows.” “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream–it is not dying.” Lennon would later claim to have taken acid over 1,000 times, becoming fairly adept at listening to the color of his dreams whilst surrendering the harshest aspects of his ego. The drug’s influence can be felt on much of the Beatles’ output, from “The Word” on Rubber Soul to “Because” on Abbey Road. In fact, the most significant music of the Sixties owes a large debt to psychedelic substances for its inspiration, including (but certainly not limited to) Bob Dylan’s 1965—67 output, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the Byrds, Love, The Who, the Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and scores of other artists. For a primer in psychedelic music appreciation you are directed to check out the two indispensable Nuggets box sets from Rhino Records (featuring liner notes and curation by Ugly Things publisher Mike Stax), as well as MOJO magazine’s compilation Acid Drops, Spacedust & Flying Saucers (Psychedelic Confectionery from the UK Underground 1965—1969).

****************

It is true that by the end of the Sixties, the great drug experiment that occurred, due to the auspices of the CIA, the mafia, and other independent agencies, turned rancid when the psychedelic insights of marijuana, LSD, and psilocybin gave way to the insidious emotional ghetto of STP, PCP, methamphetamine, and heroin abuse. By 1971, Hunter S. Thompson was already surveying the cultural debris of the drug culture, as noted in his the 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. “We are all wired into a survival trip now. No more of the speed that fueled the ’60s. That was the fatal flaw in Tim Leary’s trip. He crashed around America selling ‘consciousness expansion’ without ever giving a thought to the grim, meat-hook realities that were lying in wait for all the people who took him seriously. All those pathetically eager acid freaks who thought they could buy Peace and Understanding for three bucks a hit. But their loss and failure is ours too. What Leary took down with him was the central illusion of a whole lifestyle that he helped create–a generation of permanent cripples, failed seekers, who never understood the essential old-mystic fallacy of the Acid Culture: the desperate assumption that somebody, or at least some force, is tending the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Actually, as brilliant as some of Thompson’s prose is, he managed to get that particular assumption wrong. (Perhaps it was the abundance of Wild Turkey bourbon influencing his consciousness?) There is someone tending the light at the end of the tunnel, and that someone is everyone–the thousand points of light that cosmologist Carl Sagan spoke of is the need for every individual consciousness to step up to the plate and understand that they are the Divine source of all being.

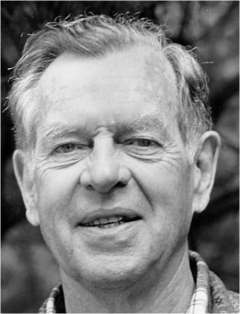

That is certainly the message espoused by two of the 20th century’s greatest promoters of psychedelics: Terence McKenna (1946—2000) and Robert Anton Wilson (1932—2007). The bedrock of McKenna’s highly opinionated elucidations is the ritualistic and sacred use of psychedelic substances. McKenna was a modern-day shaman, and the revolutionary ideas that he brought back from his psychic explorations are a staggering affront to the dogmatic twin towers of science and religion. During his entire career as a learned ethnobotanist, he insisted that the “politics of ecstasy,” i.e exploring your own consciousness, ought to be encouraged rather than demonized. “The politically most potent thing that you can do for somebody is to educate them, to give them the facts,” he said. “The spiritual realm in practical terms means the imagination, [which is] the frontier of our species. It is a race between education and disaster. We’re going to either burst out into a millennium of freedom and caring and decency, or we’re going to toxify the whole thing and turn it into an ash heap. And the responsibility falls largely on us.

“Outlandish things are going on inside the psychedelic experience. It seems to imply that the world is whatever you say it is, if you know how to say it right.

“Science is really the plumbing level of reality. It doesn’t catch the integrated nature of language, the evolution of fairy tales, the dynamics of love affairs, the quintessence of genius. These are the things that, as human beings, structure and constellate and guide and inform our world. And science has nothing to say about these things. In fact, the evidence is building that our style of society is the historical equivalent of a temper tantrum.

“The path out of the Dark Wood in which we find ourselves is cognition, thought, getting smart fast. We have to dance, sing, calculate, and drum our way out of the circumstances into which we have fallen. Poised as we are between crisis and promise, it is a metaphor for the transformation of the planet and human psychology that must take place if we are to provide a sane future for our children.”

****************

There is still much to be learned and integrated about psychedelics and the nature of our individual and collective consciousness. Although there is no “last word” on the subject, the 2010 documentary DMT: The Spirit Molecule, is a revelatory investigation into the politics of exploring your consciousness through the psychotropic substance dimethyltryptamine (DMT)–a simple compound found throughout nature, which has profound effects on human consciousness.

DMT is the psychoactive ingredient in Ayahuasca, and considered a sacramental right by the UDV (the Beneficent Spiritist Center União do Vegetal, in Portuguese: Centro EspÃrita Beneficente União do Vegetal), whose practices are protected under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. As author Graham Hancock points out, “DMT is astonishingly widely available in plants and animals all around the world, but so far nobody really knows why it’s there. Or what its function is. But Ayahuasca is much harder for the power structures that we have now, it’s much harder for them to put down, because it has been a part of legitimate religious and spiritual practice for thousands of years, certainly in the Amazon. And we can’t just dismiss all that as primitive mumbo-jumbo and superstition. We have to get to grips with that on its’ own terms.

“Our society values alert, problem-solving consciousness, and it devalues all other states of consciousness. Any kind of consciousness that is not related to the production or consumption of material goods is stigmatized in our society today. Of course, we accept drunkenness. We allow people some brief respite from the material grind. A society that subscribes to that model is a society that is going to condemn the states of consciousness that have nothing to do with the alert problem-solving mentality. And if you go back to the 1960s, when there was a tremendous upsurge of exploration of psychedelics, I would say that the huge backlash that followed had to do with a fear on the part of the powers that be that if enough people went into those realms, and those experiences, the very fabric of the society we have today would be picked apart, and most importantly, those in power at the top would not be in power at the top any more.”

Between 1999 and 2001, I spent a couple of years formally studying the Pachakuti Mesa tradition of Peruvian shamanism with don Oscar Miro-Quesada, co-author of the book Lessons In Courage: Peruvian Shamanic Wisdom for Everyday Life. During the course of those studies, I was a member of a small group lead by Miro-Quesada on two fantastic adventures: a fortnight spent in Peru and Bolivia as 1999 crossed over the dateline into Y2K; and a month in Tibet for the Saga Dawa Festival, the Buddhist New Year in June of 2000. Central to those experiences were shamanistic rituals involving ayahuasca, utilizing a set of spiritual principles that make it possible for the individual to align their free will with universal, cosmic law. As an expression and expansion of personal empowerment, the Pachakuti Mesa is a profound divination system. Shamanism, as described by Miro-Quesada on The Heart of the Healer website, is “the art of seeking and maintaining balance between humans and nature, between the seen and unseen. At the heart of shamanism is balance; without balance, healing cannot occur. In the industrialized world we are living profoundly out of balance with ourselves, each other, and nature. Lack of balance is causing rampant destruction of cultural and biological diversity, as well as profound physical and psychological illness.”

Or as McKenna puts it, “A shaman is someone who has seen the end. A shaman is somebody who has seen it all.”

As Joseph Campbell relates in the Power of Myth series, most of the ills of contemporary society stem from the social engineering that occurs when we are hoodwinked into transforming our fellow human beings from a “Thou” into an “it.” If psychedelics teach us anything, it is that all sentient beings are sacred. This is a reality that I, personally, glimpsed through my various psychedelic explorations, including many trips on LSD, but the truth of that perception really rang true to the core of my being after becoming indoctrinated into the austerity of practicing Vipassana meditation. When utilized in the proper, non-dogmatic spirit of a scientific observer, Vipassana is capable of revealing profound insights into the ever-changing nature of reality. Vipassana is a process that is never ending–it is not a place that you arrive at. That is what many of the psychedelic warriors from the 1960s took away from their experiences–that they could reach even higher states of being and gain much greater clarity into the nature of existence through intelligently contemplating oneself through the science of yoga and meditation. And learning how to turn life itself into a meditation will decrease the probability of being manipulated by the dark forces in this world. Much like psychotherapy, psychedelics are a means to get you from one riverbank of understanding to the other–they are not a means to an end. The music and art and culture of psychedelia are capable of mirroring the infinite possibilities within all of us–and when you understand that, that’s when you are really experienced. Peace.