Featured Stories

Havana Jam ’79: One World Under a Groove

The year was 1979, and the relationship between America and Cuba was contentious at best, as U.S. Representative Ted Weiss made a concerted effort to introduce a bill that would bring an end to the U.S. trade blockade against Cuba and hopefully resume normal diplomacy between the adversarial nations. Even though it was a noble effort on his part, it did nothing to ensure these economic sanctions would ever be lifted against our Caribbean neighbor to the South. That same year, Fidel Castro delivered one of his most historic speeches in an oration to the United Nations, where he heavily criticized the increased propagation of nuclear missiles.

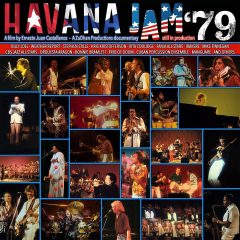

Somehow, the music industry acted as a kind of goodwill ambassador to bridge the cultural chasm that existed between both countries during that volatile chapter in world history. In 1979, a core group of American musicians, along with CBS Records President Bruce Lundvall and several of his colleagues at the label, traveled from New York to Havana, Cuba to represent the United States in a grand-sweeping cultural exchange. The music festival, spanning the course of three days in March of that year, would unite some of the industry’s most renowned artists from both the U.S. and Cuba in concert. The roster of stars on the Cuban side included Pacho Alonso, Juan Pablo Torres, Los Papines, Irakere, Orquesta Aragon, and more. On the American side, Stephen Stills, Bonnie Bramlett, Trio of Doom, Kris Kristofferson, Rita Coolidge, Weather Report, the Fania All-Stars, the CBS Jazz All-Stars, and Billy Joel fleshed out the billing in one of the most important musical overtures to ever bestow Rock and Roll. It was called “Havana Jam.”

The San Diego Troubadour recently spoke with renowned author and filmmaker Ernesto Juan Castellanos, who shared information about the project he is spearheading, by way of the documentary Havana Jam ’79, which captures the events of the music festival that took place March 2-4, 1979 at the Karl Marx Theater. At the time this interview went to press, the film is still a work-in-progress.

Born on February 14, 1963 in Regla, “a small but very popular town near Havana,” but now residing in Miami, Castellanos reflected on life, family, the Beatles, and Havana Jam ’79, the film that shines the white-hot spotlight on a chapter in rock ‘n’ roll history that witnessed the U.S. and Cuba uniting together in song 40 years ago.

Looking back on your beginnings, what was it personally like for you to grow up in a country defined by its communist origins?

I was born four years after Castro took power, so there was a lot of trial and error in the social process being built. Like any other Cuban kid, I was indoctrinated from an early age. Of course, the country tried to follow a Soviet line and everything having to do with the U.S. was considered bad and decadent. It was precisely my two older brothers who opened the doors for me to the world of rock and the Beatles, who were also considered a bad influence for the Cuban youth, in spite the fact they were British and not Americans. But I would be lying if I told you that I didn’t have a happy childhood, despite the scarcities and government-imposed censorship.

What kind of impact did Fidel Castro have on your early years?

Castro didn’t mean much to me in my early years. I cared more about children’s games than politics. The doctrine imposed on children back in the day was mostly about Che Guevara. I remember there was a slogan that all children had to repeat every single day for years like parrots before starting classes: “Pioneers in favor of Communism, we shall be like Che.”

For many young Americans attending high school, there is a certain predictability that outlines one’s adolescence and completion of education as they reach graduation. But for you, as a student living and studying in Cuba, life was more than just formulating a plan to zip through high school and then settle on a chosen occupation immediately after graduating from high school.

I attended high school a bit far from my house, as there were no high schools in my neighborhood. It was precisely in high school when I fell in love with the syndicated radio show “American Top 40,” hosted by Casey Kasem. I would listen to the show twice every weekend, on Saturdays and then again on Sundays, on a couple of Miami radio stations that had a very clear signal in Havana–WGBS and WQAM. I listened to Miami radio stations every day, something that got me in trouble with the authorities more than once. Back in the ’70s, whoever listened to or played American music and wore long hair and jeans, fell into the “fearful” category of “ideological diversion,” a term implemented by the Stasi in the German Democratic Republic and passed on to the Cuban Ministry of the Interior. Many young people were incarcerated or expelled from schools after being labeled as “ideological diversionists,” because they fancied American culture. Rock music and the Beatles were the spark that encouraged me to learn English so that I could understand the lyrics. So, when it was time for me to decide what to study in college right after high school, I picked English.

It has been noted that you are a purveyor of “all things Beatles.” When, exactly, did you jump on the Beatles bandwagon and embrace them as artists?

It was precisely my older brothers who opened that door for me. They would bring Beatles albums home back in the late ’60s, early ’70s, and played them on our old record player. I grew up with that music as my playground. As I mentioned before, it was through the Beatles that I learned English faster than I did at school. Of course, you couldn’t buy American or British music in Cuban record stores, so an underground passing around of records developed very quickly, as I believe happened in other Soviet bloc countries. My older brother had a childhood friend who was a steward with the Cuban airlines, and he had all the Beatles discography. So, I would go to his house on a regular basis and copy the whole Beatles catalogue to cassettes. Through the years, I became a Beatles expert. In 1996, through a mutual friend, I managed to convince the Cuban Minister of Culture to let me organize the first Beatles Colloquium ever held in Cuba. For almost four decades, since Fidel Castro came into power, no one had ever spoken publicly or officially about the Beatles or rock ‘n’ roll in Cuba. To make a long story short, in a four-year span, I brought to Cuba John Lennon’s original band, the Quarrymen, Beatles photographers Jan Oloffson and Robert Freeman, the Beatles official biographer Hunter Davies, Beatles expert Peter Nash, and producer George Martin. From being a fan, I eventually became the Beatles authority in Cuba, and the Beatles became a job to me. I published four books about them, and my initial work, four years earlier, led to the dedication of a statue of John Lennon by Fidel Castro himself, on December 8, 2000. However, I didn’t do this alone. A very faithful group of friends supported me during those years.

Those tomes about John, Paul, George and Ringo…care to divulge their titles?

Sure! I’ve authored the following: Los Beatles en Cuba: Un Viaje Magico Y Misterioso, El Sargento Pimienta Vino A Cuba En Un Submarino Amarillo, John Lennon En La Havana With A Little Help From My Friends, and La Guerra Se Acaba Si Tu Quieres.

Of all the Beatles, who do you personally identify with the most?

That’s a hard question, as they were all good and had their own personal touch. But if you ask me again, I will tell you that I’ve always identified more with John Lennon.

Who or what turned you on to the idea to pursue the arts, literature, writing, and filmmaking, when you began exploring your creative perimeters?

It was precisely the Beatles Colloquia that opened doors to the world of literature for me. I wrote those four books about the band and a number of stories in Cuban magazines and newspapers. In the early ’90s, I had started to work as a producer and location manager for many British and U.S. film and news crews that went to work in Cuba. It was there where I developed my passion for news and documentaries. So, when I wrote my books, I wrote them from a journalist’s point of view: interviews, travel stories, chronicles, etc. I never went to film school or even studied journalism. I learned the craft by diving headfirst into the real world. Then, I was the Cuban producer for most of the foreign bands that played in Cuba in the 2000’s: The Manic Street Preachers, Audioslave, Kool and the Gang, and Simply Red. And in 2007, I was part of the production team at the Live Earth concert in London.

Let’s discuss Havana Jam ’79. What prompted you to become involved with the event that awakened a culture oppressed by its Communist regime? How familiar were you with the American artists who performed at the Karl Marx Theatre in Cuba on March 2-4, 1979?

Ten years ago, a friend asked me to write a story about the 30th anniversary of the Havana Jam to publish in one of Cuba’s top newspapers. So, I interviewed the multi-Grammy award winner, Chucho Valdes, who was the front man for Irakere back then, and his story was so amazing that I decided to borrow a camera from a friend, and I started to interview all the Cuban musicians and execs who were still around. I didn’t attend Havana Jam. Keep in mind, it was not a public event, and I heard about it the week afterward, when a friend told me he had gone to a concert where one of the bands filled the stage and the front rows of seats with a weird, thick smoke. People started to run, thinking there was a fire. Of course, I didn’t believe him back then. Years later, while shooting the documentary, I learned that he was talking about Weather Report.

Then, I heard from different sources that Billy Joel had played. Being an “American Top 40” fan, of course, I knew who he was. I also knew of Rita Coolidge and Kris Kristofferson, and I associated Stephen Stills with Crosby, Stills and Nash. I didn’t know the rest of the musicians. The Fania All-Stars was not my thing, as jazz wasn’t either. I only regretted having missed Billy Joel. Now, here in the U.S., I have managed to interview Billy Joel and his band members, plus other musicians and CBS execs. I have collected a lot of stories, documents, video footage, music, and photos. I fall in love with the project more and more every day, as I discover how wonderful that festival was for all those involved. I haven’t heard anything but good memories. Everyone talks about the Havana Jam with passion, and I’m pretty sure I’m helping tell the history that hasn’t been told properly. And at the same time, I’m paying my respects to Bruce Lundvall (the organizer of Havana Jam), who made it all happen and to those who were there and are no longer with us.

It’s amazing how much territory you’ve gained and covered while you’re currently involved with the Havana Jam ’79 project. It’s no small feat as you work tirelessly to ensure that this documentary gains momentum and gets out to the masses. How did you go about securing all those iconic images that were taken during the event to now being part of your own personal possessions?

It’s been no easy task, believe me. My first collaborator was the Cuban Ministry of Culture. They gave me access to their photo archives. I personally opened files with negatives that hadn’t been touched in 30 years. A good friend did an excellent job scanning nearly one-thousand black-and-white photos taken by three or four professional photographers at Havana Jam. It was like spotting a goldmine. I had the exclusivity to be the first guy to see all that bunch of photos together. Then came the painstaking process of putting them into specific categories: bands and the dates in chronological order.

My next collaborators were musicians whom I contacted via e-mail. Peter Erskine, Weather Report’s drummer, sent me a bunch of color photos he had taken in Havana. That was amazing. I was still living in Cuba, and Peter gave me the opportunity to see behind-the-scenes shots of musicians behaving like human beings, having fun at the beach, backstage, walking around Havana. Amazing! Then, when I moved to Miami, I contacted Bill Freston, who, in 1979, had been Bruce Lundvall’s personal assistant and confidante. He mailed me all the CBS documentation and photo archives that he still owned.

Another Havana Jam photographer, Benno Friedman, also mailed me his entire Havana Jam archives, hundreds of slides that had so much fungus on them that I had to fly to Havana and trust the cleaning job to my old friend and photographer, Julio Larramendi, who managed to recover them all and leave them in pristine condition.

Another important source was Billy Joel’s archivist, the late Jeff Schock, who also gave me a good bunch of photos, not only of Billy in Havana but also of other musicians. We had started a mutual collaboration a couple of years before. I had previously donated to his archives the audio tapes of Billy’s full Havana Jam concert, something that they didn’t even know existed, as his then-wife and manager, Elizabeth Weber, had prohibited any audio or video recording. But I had managed to find these audio tapes from two different sources, one of them from a journalist friend who had recorded the whole concert on his cassette recorder. Several other people involved in Havana Jam have given me access to their extensive archives, slides that hadn’t been touched in almost 40 years.

Also, James Lipton, who was the director and producer of the documentary that was filmed about the event but never shown on TV, gave tons of his slides; Bonnie Covelli, who was Bill Freston’s secretary, gave me all her photos and archives with interesting information such as rooming details of who doubled up in the hotels with whom, travel schedules, and expenses; and Tor Lundvall, Bruce Lundvall’s son, gave me access to his dad’s archives, photos, and personal Havana Jam memorabilia.

I’ve been blessed with all these collaborations. People who didn’t even know me trusted me with their original slides and documents. That was the fuel that kept me going and that proved just how important and historic this event was, and these people were trusting me with something so personal.

It’s been noted that you interviewed one of Rock’s most beloved, enduring superstars for your documentary. What was it like for you to sit down and talk with Billy Joel, who is still going strong in music with his permanent residency at Madison Square Garden?

Interviewing Billy Joel, not once but twice, has been one of the biggest professional accomplishments I have had in my whole life. Getting him to tell me on camera his part of the story has been incredible. We spoke about many things, but the story of his dad living in Cuba, after many Jews had to flee Nazi Germany to save their lives, was narrated with great affection. His father’s stories about Cuba made him fall in love with the island, since he was a kid.

In the second interview, which was on camera, I brought my son, Dhani, along as my camera and lighting assistant. He was then a sophomore at Loyola University in New Orleans, majoring in violin performance. I asked him to bring his violin with him, as you never know what can happen in an interview like that. The moment Billy saw him get out of the car with the violin, they made an instant connection. When we finished the interview, he invited my son to jam in his living room. They jammed for about 30 minutes or so, and they moved from Cuban music to Classical to Jazz to Blues to Rock and Roll and, of course, a couple of Billy’s songs which my son didn’t know at the time. It was incredible! I have it all on video. To make a long story short, he asked my son if he wanted to join him onstage at Madison Square Garden, playing “The Downeaster Alexa” and maybe “Where’s The Orchestra?” A month later, Dhani played with him in front of 25,000 people at the Garden, making it the very first time a Cuban played with Billy Joel. Together, they made a bit of history there.

What has life taught you the most about being Ernesto Juan Castellanos?

I’m 56 years old, and life has shown me all its colors, sides, hills, and holes. I consider myself a very blessed man. In Cuba, I was an accomplished writer. Moving to the U.S. six years ago has been one of the greatest challenges of my life. Here, I had to start a life totally from scratch. I left behind my days as a writer and journalist. I left behind my house, my friends, and most of my possessions. I left behind my accomplishments to live in a country where nobody knows me or my works. But one of my biggest goals was to give my son the chance to make a future out of his life. He has studied the violin since he was six years old and pursuing his violin studies was his top priority when we came to the United States, the land of opportunity, where the sky’s the limit. Well, six years later, he has just graduated from college as an accomplished violinist. Now, he wants to pursue a master’s degree in violin performance. He is very talented, and he has already played with Billy Joel…he’s waiting for new doors to open.

To find out more about Havana Jam ’79 and to see the trailer for the upcoming documentary, please visit https://m.facebook.com/havanajam79/

Photos courtesy of Benno Friedman.