Yesterday And Today

Frankie Laine: A Century of “Mr. Rhythm”

Frankie Laine

Laine during a radio broadcast in 1949

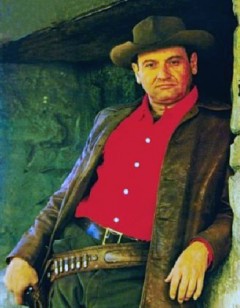

Laine during his “cowboy” days

During his post-World War II ascension to the top of the recording charts as one of the most original voices in jazz and popular music, Frankie Laine picked up the moniker “Mr. Rhythm.” It was a fitting nickname: he rarely stood still, and his seated audiences often jumped out of their chairs to cheer him on.

Sixty-seven years after his breakout hit — and six years following his death at age 93 — Laine will be receiving a nickname with an emphasis on a local angle.The streets of his beloved Point Loma neighborhood will be adorned with banners proclaiming him as “The Prince of Point Loma.” It’s all part of a 100th birthday celebration of a singer who relocated (but never truly retired) to San Diego in 1968. Laine aficionados from international starting points will convene at the Kona Kai Club on Shelter Island for a luncheon/concert on March 24.

Point Loma, Shelter Island, and San Diego Bay are decidedly more picturesque than the humble surroundings of Chicago’s West Side, where Francesco Paolo LoVecchio was born to Sicilian immigrants John and Anna LoVecchio on March 30, 1913. Frankie LoVecchio’s childhood and the adaptation of his professional stage name Frankie Laine were told in Laine’s critically acclaimed autobiography (co-written with popular music historian Joseph F. Laredo) That Lucky Old Son. The book’s title was a gentle pun on one of Laine’s most recognizable ballads, “That Lucky Old Sun.”

As a child, Frankie existed in a word of tranquility and chaos. The former was represented by the singing of Latin hymns like “Stabat Mater” within the safe confines of the Church of the Immaculate Conception. But outside the church doors, a different Chicago existed: a city of speakeasies and mob warfare. Frankie’s father was the barber who would make house calls to give Al Capone a haircut and a shave and lived to tell the experience. Unfortunately, Frankie’s grandfather on his mother’s side, Salvatore Salerno, wasn’t so fortunate; although he often negotiated truces between rival gangs, one side visited him in his grocery store and rewarded him on his conflict resolution skills by killing him in a barrage of bullets. Twelve-year-old Frankie saw his grandfather’s body and the early exposure to the gratuitous violence left him with his most haunting childhood memory.

Music would provide a much-needed alternative. After gaining confidence by singing at family gatherings and teenage parties, the former choirboy pondered an interesting proposition: could he combine the blues singing of Bessie Smith with the stage charisma of Al Jolson? Both entertainers had bowled Frankie over with their talents. The discovery of Smith had come through a happy accident. The LoVecchio family had moved to a new home, where some records had been left behind by the prior occupants. Found among the predominately Italian recordings was a Smith blues 78-rpm disc. In his autobiography, Laine wrote that he had “no idea how the disc made its way into this collection of high class music, but thank goodness it did. I can still close my eyes and visualize its blue and purple label. It was a Bessie Smith recording of ‘The Bleeding Hearted Blues,’ with ‘Midnight Blues’ on the other side. The first time I laid the needle down on that record I felt cold chills and indescribable excitement. It was my first exposure to jazz and the blues, although I had no idea at the time what to call those magical sounds. I just knew I had to hear more of them!’ Jolson’s bigger-than-life personality came over well on the silver screen, as Frankie ditched school one day to see two matinee showings of The Singing Fool.

Frankie had time to work on his act in front of a bedroom mirror. Singing opportunities in Chicago were few and the stock market crash of 1929 severely challenged what little money Americans had for leisurely pursuits. But one of the most peculiar fads in the history of American popular culture allowed Frankie a strange entrance into show business: the marathon dance contests. A Depression Era phenomenon that surprised future baby boomers when it was depicted in the 1968 Jane Fonda movie, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, the marathon broke down contestants physically and mentally. In Frankie’s situation, it earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records, before his name changed to the Frankie Laine of gold record reputation. In 1932, Frankie and partner Ruthie Smith danced a collective 3,501 hours over a stretch of 145 days in a marathon contest held at Young’s Million Dollar Pier in Atlantic City. Frankie outlasted Joie Ray, a former track star in the Olympic Games. “Before the grind started Ruthie and I ate a good meal but didn’t have anything to drink, Laine wrote. “Joie Ray did, and that was his fatal mistake. As the grind extended, so did Ray’s bladder. Inevitably nature took its course and, since the man wasn’t allowed to leave the floor, he wet his pants and was disqualified. Ruthie and I became the world champions and won a very handsome prize.”

As the economy improved, the marathon dance craze faded. Before he walked away from the floor, Frankie performed during break time and met future stars on the circuit, including Red Skelton, Baby Rose Marie (who grew up to play man-chasing Sally Rogers on the “Dick Van Dyke Show”) and an extroverted 14-year-old Anita O’Day. “[Anita] would follow me around like a little puppy after every song I sang and pepper me with questions: ‘Why did you pick that tune? Why did you phrase like that? How come…how come…how come?’” Laine wrote. “Of course, when they found out that she was underage they pulled her right off the floor, but her brief stint in the contest marked the beginning of my association with a lady who became one of our great jazz stylists, Anita O’Day.”

Laine attempted to establish himself in the New York jazz circle but found steady club work elusive. At one low point, he was relegated to spend the night in Central Park — not at one of the landmark hotels but on a rather uncomfortable bench where he survived on a carefully rationed supply of Baby Ruth candy bars. The next show biz plan of attack found him out in Los Angeles. At least he could stay warm while he was pounding the pavement.

During his California years in the ’40s, Laine’s fortune slowly turned for the better. He recorded some singles for the predominantly black Atlas label. Early sessions on Atlas saw Laine backed by Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers, a talented trio featuring guitarist Oscar Moore (King Cole Trio) and pianist Charles Brown, whose sensuous “Merry Christmas Baby” became a yuletide classic. Some of Laine’s most ebullient work remained unheard for decades. Famed recording engineer Wally Heider (Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young; Van Morrison; Tom Waits), came into possession of sealed transcription discs recorded in LA by Laine during the ’40s. They had been found stored in a radio station in Oregon in 1980. Cleaned up for sound quality by Heider and released over several albums during 1984-85, the arrangements swing like crazy, and Laine and the session artists are having the time of their lives.

In 1946, an obscure ballad from the Tin Pin Alley days of the ’30s was resurrected by Laine at Billy Berg’s Nightclub in Hollywood. The song was “That’s My Desire,” a 1931 composition by Helmy Kresa and Carroll Loveday. The results were electrifying: a buzz grew around the room, lines formed outside the club, and a major record label — Mercury Records out of Chicago — came knocking. Gold Records followed in quick succession; “On the Sunny Side of the Street”/ “Blue Turning Grey Over You” (1947), “Two Loves Have I”/ “Put Yourself in my Place” (1947), and “Shine”/ “We’ll Be Together Again” (1948). “That Lucky Old Sun” (1949) was a radical departure for Laine, a spiritual folk song of a man plagued by life’s hardships.

To understand Laine’s startling yet successful transition from hep jazz cat to a Stetson-wearing, rootin’ tootin’ son of a gun, an examination of post-war American popular culture is in order. Cowboy radio serials made a smooth ride from the wireless to television. The ’50s and early ’60s were the golden years of the television western. Take the entire combination of today’s TV diet of CSI crime labs, reality shows, and talent contests, and they would pale in comparison to America’s once insatiable hunger for Old West mythology. There were over 50 television westerns in the ’50s alone.

After the success of novelty songs like “Mule Train” and “Cry of the Wild Goose” — pitched to Laine by his A&R man, Mitch Miller — the singer became identified with western songs when he switched over to Columbia Records in the ’50s. Many a TV viewer has watched the late show to see Gary Cooper in High Noon and to hear Frankie Laine sing the iconic theme (“Do Not forsake me, oh my darling…”) only to discover that the film used Tex Ritter instead of Laine. Ironically, the version by Laine was the better seller of the two. But it was Laine whose voice was heard above Kirk Douglas’ name in Gunfight at the OK Corral or Glenn Ford’s in 3:10 to Yuma. Laine’s jazz fan base were befuddled by the singer’s new home on the range. In hindsight, it was a savvy business move. While many of his contemporaries found their careers slowing down due to the pending rock ‘n’ roll revolution, Laine won the kids over, particularly the younger set who were playing cowboys and Indians in their yards or sporting the Davy Crockett coonskin caps. Just like his famous rendition of “Rawhide,” Laine kept “those doggies rollin…”

Laine’s most fervent fan base turned out not to be in North America but across the pond. In the comprehensive DVD of his life, Frankie Laine: An American Dreamer, Ringo Starr associated the singer with “many teenage experiences, and it was a lot to do with fairgrounds and the teenage madness as you go through. Frankie was always blasting out ‘Jezebel,’” said the Beatles drummer. “He was so powerful, that’s why I loved him. He was just so dramatic and powerful.” Laine’s music also impressed another working class English teen: Bill Wyman, who would later play bass guitar for the Rolling Stones. “I went straight to a record shop in Anerley where I bought an old secondhand wind-up player and a box of needles,” wrote Wyman in his autobiography, Stone Alone. The 16-year-old then bought what he called “my first two precious records: Les Paul and Mary Ford’s ‘The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise,’ which was not new but featured Les Paul’s marvelous revolutionary multi-track guitar playing; and Frankie Laine’s punchy ballad ‘I Believe,’ which went to Number One in America and Britain.”

During his last few years at Columbia, Laine made non-western contemporary recordings designed to appeal to the AM radio youth market. He had at his side producer Terry Melcher (son of one of Laine’s duet partners, Doris Day) who would, a short time later, begin his seminal work with the Byrds. Joining Melcher and Laine was Jack Nitzsche, a hot LA-area arranger whose name would later appear on albums by the Stones, Buffalo Springfield, and Neil Young. 1963 was a memorable year for Roy Orbison and Gene Pitney, two vocalists at their peak whose recordings had the same emotional wallop Laine was delivering to his followers. Laine’s “Don’t Make My Baby Blue,” written by the Brill Building songwriting team of Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, featured the talents of LA’s famed Wrecking Crew session musicians. Although the song would later be given a rigorous workout by British rockers, the Move, sales were surprisingly light for the Laine version. The followup single was “I’m Going to Be Strong,” which ironically was an international smash for Pitney one year later. Fifty years later, the Melcher-Nitzsche sessions featuring Laine are highly sought by Laine fans and ’60s music collectors.

Melcher and Nitzsche were not able to put another gold record on Laine’s wall, but singer-songwriter Marty Robbins did. In the turbulent year of 1969, Laine pulled out all the stops in his riveting version of Robbins’ “Lord, You Gave Me a Mountain.” The ballad became a concert essential for both Laine and one of his life-long fans, Elvis Presley.

Laine understood and appreciated Robbins’ songwriting skill: the former had done some songwriting himself. In the appendix section of his autobiography, a list of his songwriting credits show Laine getting the opportunity to work with some of the most famous names in the Great American Songbook; “What Am I Here For?” (Laine with Duke Ellington); “Put Yourself in My Place Baby” (with Hoagy Carmichael); “It Ain’t Gonna Be Like That” (with Mel Torme); “I Haven’t the Heart” (with Matt Daniels); “Magnificent Obsession” (with Fred Karger); and “Torchin’” (with Al Lerner). Laine’s most frequent collaborator was his arranger and dear friend, Carl Fischer. It took some time for Laine to continue his career with enthusiasm after Fischer’s death at the young age of 41 in 1954. Among the several compositions Fischer and Laine collaborated, “We’ll Be Together Again” has become — by any criteria — an American standard. The names of the artists who have recorded the tune (easily more than 100) reads like a who’s who of jazz and popular music: Louis Armstrong, Kenny Clarke, Stan Getz, Chico Hamilton Trio, Quincy Jones, Stan Kenton, Anita O’Day, Joe Pass Trio, Oscar Peterson, Horace Silver, Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sammy Davis, Jr., Rosemary Clooney, Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, and Tony Bennett.

Laine’s humanitarian efforts outside the recording studio were legendary. He supported Nat King Cole’s TV variety show by being the first white artist to appear, and while Laine’s guest spot inspired Tony Bennett and Rosemary Clooney to follow suit, NBC dropped the Cole series due to low sponsorship support. During the Selma-to-Montgomery era of the Martin Luther King Civil Rights movement, Laine performed as part of a free concert. Laine’s activism took on a local perspective after he and his first wife, actress Nan Grey (who would pass away in 1993) moved to San Diego permanently in 1968. One of his most famous charity drives was providing shoes for the homeless community. Laine’s name also became synonymous with charitable work for St. Vincent de Paul and the Salvation Army. For many years, Laine’s portrait appeared in the lobby of Hillcrest’s Mercy Hospital where he was an emeritus member of the board of directors.

San Diego returned love to the “Lucky Old Son” by presenting him with the 1999 Lifetime Achievement honor at the San Diego Music Awards. Laine gave his last performance in 2005 on a PBS music special singing the song that started it all, “That’s My Desire.” He was happily remarried to a San Diego woman, Marcia Ann Kline, and the couple enjoyed socializing in their Point Loma home. On February 6, 2007, Laine passed away due to heart failure.

The big gala on Shelter Island represents a labor of love for Encinita’s Jimmy Marino (producer of the American Dreamer DVD) who operates JFM Productions. “I created JFM Productions in 1995. My mission was to create broadcast quality film and television products for the national and internationally audience,” said Marino.

With the serene backdrop of San Diego Bay, the 100th birthday celebration at the Kona Kai Club will be jumping with the swing sound of Benny Hollman’s Big Band Orchestra. Hollman and Laine had a close bond as Hollman — whose music resume dates back to San Diego High in the ’50s — served as the singer’s final conductor. Veteran entertainer Bobby Arvon will be the lead vocalist for the afternoon, presenting a set that will encompass the different genres where Laine excelled.

Marino, a professional drummer, also grew up in San Diego, attending Lincoln High and San Diego State. He kept the beat for the Strangers, a local band who had a 1959 chart record with “Caterpillar Crawl” and featured future California country rock legend Joel Scott Hill. When the long, behind-the-scenes planning for the tribute is completed, Marino will time to reflect on his musical mission. “I became a fan when I was just a boy because my older sisters were huge Frankie Laine fans. They bought all his records and played them over and over again. My folks were also fans as they loved that Frankie was also Sicilian. I grew up listening to his music, and when I became a professional musician I respected him all the more. I was able to perform his music for many years before I actually became his producer/ manager. Having a close relationship with one of the greatest singer/ entertainers, was the highlight of my musical career. To be associated with the legendary Frankie Laine was an honor, and the most fulfilling opportunity of my lifetime. Frankie’s legacy is marked by his 21 gold records, over 200 million records sold, five movies, his own TV show, countless appearances on TV shows both here and abroad, singing the title song for several movies and TV shows including ‘Blazing Saddles’ and of course ‘Rawhide.’ Frankie Laine gave the world the gift of his unique voice and his hope was he left this world a better place — ‘That’s His Desire.’”

Frankie Laine’s 100 Birthday Celebration will be held Sunday, March 24, 1 p.m. at the Kona Kai Resort on Shelter Island. Visit www.frankielaine.com for ticket information.

LOCALS LAUDING LAINE

It’s not difficult to track down testimonials to Frankie Laine, especially when they emanate from your own back yard. Here’s what three prominent San Diegans had to say about “Mr. Rhythm”:

“I think that Frank probably was one of the forerunners of . . . blues, of . . . rock ‘n’ roll. A lot of singers who sing with a passionate demeanor–Frank was and is definitely that. I always used to love to mimic him with ‘That’s . .. my…desire.’ And then later Johnnie Ray came along that made all of those kind of movements, but Frank had already done them.” — The late Pattie Page

“He’s one of the best, I think. I don’t think Frank ever really got his comeuppance in terms of standard, as far as fame and making money and all that stuff — like Sinatra and Como and all those guys did, because Frank is in the same ballgame. [He was] way ahead of the younger crowd that came along behind him. I feel that he was cheated a little bit — always felt that way about him, that he deserved more than he got.”

— Mundell Lowe, jazz guitarist

“It was awhile back when Frankie was still with us and celebrating his 75th year that Frankie Laine collectors and fans from all over the world descended on San Diego for a birthday bash and a record collecting mish mash. At Folk Arts Rare Records I had visits from Frankie Laine collectors from Finland, Germany, Italy, Taiwan, Japan, Australia, India, Iran, Argentina, Zimbabwe, and most other parts of the world where his music might have traveled. At the same time I had a collector from Gaza in Palestine and a collector from Tel Aviv in Israel looking through a stack of Frankie’s long play records and 78s and exchanging bits of information about the man. I later told Frankie, when he visited my shop, about this contribution his music had made to peace in the Middle East. I also told him that I had started that week with about a hundred of his LPs in stock and probably near 200 78s and 45s and I sold every one of them. So not only was the contribution made to peace but to the paying of the rent at Folk Arts Rare Records. He told me that he was glad to help.” –Lou Curtiss, Folk Arts Rare Records