Yesterday And Today

Clint Davis’ Journey to the Motherland, Part Two

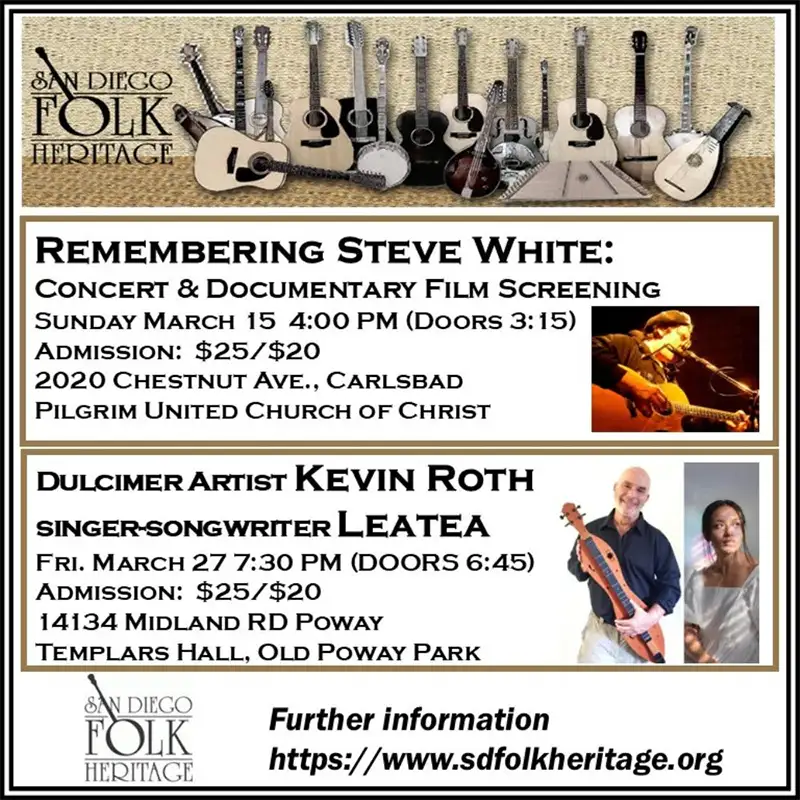

G Burns Jug Band: Batya MacAdam-Somer, Clinton Davis, Jonathan PIper, Tim McNalley, Meghann Welsh. Photo by John Hancock.

Louisville Cemetery at the grave of Sara Martin, the vocalist whose song, “Jug Band Blues,” we recorded on our second album, The Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe. Her previously unmarked grave received this marker in 2014 through the joint efforts of the Jubilee and the Kentuckiana Blues Society.

….in which we learn the fate of San Diego’s G Burns Jug Band as they travel to the historic homeland of jug band music.

Louisville, Kentucky is a special place to me. It has always been a town I knew and explored primarily through music. I grew up in a small community nearby where, like most young rural people, I often lamented that there was “nothing to do.” Going to see a movie, buy a CD, or even buy a pack of guitar strings meant buckling up for an hourlong drive down I-71 (not “the 71,” mind you). But it was worth it. Louisville has always had a thriving music and cultural scene, I suspect, because it is the perfectly sized city: large enough to attract a critical mass of creative artists, but small enough to avoid descending into the baroque excesses of a Williamsburg or Portland.

My dad is a musician and brought me to the city to see his favorite performers and songwriters whenever venues allowed. Included in these trips was an annual visit to the Kentucky State Fair in Louisville. We’d tour the horses and livestock, talk to Freddy Farm Bureau, eat fried food, and Dad would take us to see the Juggernaut Jug Band, a folk revival group that formed in the ’70s and played the fair every year. It was always a fun memory of being a kid but also my introduction to the idea of “jug band music” and its connection to the place in which we lived.

Jug bands and folk music generally didn’t become a big part of my life for years to come, but Louisville remained my source for music. By the time I was in high school and old enough to drive, I was going there at least once a week. I searched for records at Ear-X-Tacy. I bought my first acoustic guitar at Guitar Emporium (we used it on our tour). I went to all-ages shows at the Keswick Democratic Club. I had my first experiences of being part of a music scene: of having bands that I saw often, whose merch I bought religiously, and with whom I occasionally shared a word.

Aside from my personal experience, Louisville is a special place for the music we play because it was home to the first bands with jug-blowers to record. In the 1920s, black bandleaders like Earl McDonald and Clifford Hayes used jugs in bands inspired by the jazz music they heard coming out of New Orleans, and vaudeville blues vocalist Sara Martin used a jug blower on her recordings. Their work would inspire bands in other cities across the South to expand the idea of “jug band music” to incorporate virtually all of black musical culture in America at the time. Depending on the band or even the tune, the recordings of jug bands could span jazz, ragtime, vaudeville, or blues. Most amusingly, so-called “sanctified jug bands” repurposed their whiskey vessels as a vessel for the Lord by backing up gospel choirs.

In other words, jug band music as a style is hard to pin down or define. It seems to exist in between prevailing categories of American music. It’s sometimes too jazzy to be blues, other times too bluesy to be jazz. For blues lovers, even the bluesy jug bands seem to fall between the cracks. Blues history is anchored around images of the southern country bluesman playing acoustic guitar solo on the porch or, on the other hand, the electrified bands of northern cities like Chicago. By comparison, there’s very little love given to the blues mandolin players or blues fiddlers of jug bands from southern cities. All of this in-betweenness is even mirrored in the geography of the old jug bands and their connection to the Mississippi River, which divides the East from the Midwest, and the Ohio River, which sits in between the South and the North.

This history, and more specifically the neglect of this history in the grand narratives of American music, was the impetus for the formation of the National Jug Band Jubilee. Members of the Juggernaut Jug Band, their families, and roots music lovers of Louisville launched the festival in 2005 to bring renewed attention and appreciation to this music through live performance, educational outreach, and historical preservation.

It was a great honor to be invited to the Jubilee, and though I looked forward to it a great deal, I had not anticipated the feeling I experienced as my own personal nostalgia began to overlap with this history which had always felt a little more distant or abstract, as fascinating, wonderful, and fun as it was. Our stay in Louisville began with an afternoon assembly performance organized by the Jubilee at Lincoln Performing Arts School, a cutting-edge publicly funded elementary school with an arts-centric charter. We have played many shows in which I’ve said my few words about the history of jug band music, but at this show, I couldn’t help but remember being the age of those students and hearing that very story myself in that very city. As if that wasn’t reward enough, we were privileged to have roots music scholar and journalist Barry Mazor in the audience, who went on to recount our concert in the Wall Street Journal later that week.

The Jubilee itself was a beautiful event at the Brown-Forman Amphitheater on the banks of the Ohio River with a great deal of my extended family in attendance. Our set fell between the wonderful Ever-Lovin’ Jug Band, with whom we formed a superband with Jim Kweskin last January, and the Juggernaut Jug Band themselves. After the Juggernaut’s set, I found bandleader Stu Helm backstage. We shook hands and he immediately began sharing stories of seeking out and learning from the last of the city’s black jug blowers in the early days of his band.

The following morning, Meghann and I visited Louisville Cemetery, the oldest African-American cemetery in the city and final resting place of many of Louisville’s jug band musicians. It is smaller and more modest than others in the city. As charming as the relatively shaggy, partly unmowed grounds were, its condition seemed to reinforce the necessity of the Jubilee. Until recently, many important black Louisville musicians, jug band or otherwise, had no marker on their burial site. The Jubilee and the Kentuckiana Blues Society have worked together in recent years to correct this by commissioning headstones commemorating the contributions of these individuals to American music.

From there, Meghann and I traveled an hour outside of Louisville to see my family and my hometown. While we were there, spending the last day of our amazing trip, we went to the same place I always go every time I visit home: a lookout point my great-grandfather helped build during the Great Depression for the WPA. From it, you can see all of the town and the massive Ohio River. I sat there a while and let my mind wander a little after a week of constant motion.

I watched the barges float down the river more or less as they have for over a century. I thought about all of that water working its way back to New Orleans where we had started our trip. I thought about all the roustabouts that had spread their songs through the river valleys while working on those boats. I thought about the Old Darling Distillery, which produced bourbon in town in the late 19th century, and wondered if the old musicians ever got their hands on some of their product (where’d you think all those jugs came from?).

There was an all-too-brief sense of clarity and, again, connection between our music, my past, and the history of a place, which will always be, in some sense, home. In the middle of my daydreaming, a lyric came to me from an old jug band song: “You may leave, but this will bring you back.”

Clinton Davis, Ph.D., is a freelance musician and educator based in San Diego. He performs music from a variety of American traditions on guitar, banjo, piano, mandolin, fiddle, and harmonica–most visibly with the award-winning G Burns Jug Band. For information about his music or lessons, visit http://clintonrossdavis.com