Featured Stories

Bob Seger and Bruce Springsteen: A Discussion

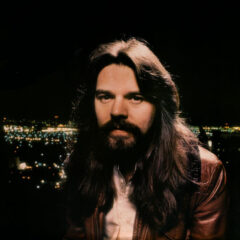

Why Bob Seger isn’t as highly praised as Springsteen is worth asking, and it comes down to something as shallow as Springsteen being the cuter of the two. In areas where we all say it counts—talent—Seger has it over Springsteen by huge margins; he’s a far better singer (one of the most underrated in rock ‘n’ roll), and he’s a superior songwriter. It’s not as if Seger hasn’t vainly dallied with fads and pretentiousness; I have enough old Seger albums to testify that his worst music is as misguided as the grimmest rock music ever released. But he’s been a trouper, a constant tour dog, a tireless professional, and an eternal journeyman who has always added more tricks and licks to his repertoire. The longer he played, the better his singing and songwriting chops became. Springsteen isn’t a phony by any standard, and there’s something likable about the guy even though I think his music is so much less than rock critics find it. His lyrics are an occasionally interesting stew of impressions that are more muddle than the atmosphere, or even mood.

For all his musical fanfare, for all his verbosity and blaring dynamics, Springsteen has always seemed like someone who was on the brink of saying something memorable, only to choke. Seger, in mid-career, dropped any ambition he had to become the next Dylan and Beatles and developed a lyric style as natural and sweetly clear-eyed as anything Chuck Berry himself could have worked out. Seger continued to suffer from lapses of taste and inspiration, of course—remember that he never transcended his journeyman status—and produced some albums where he was witlessly trying to rewrite “Night Moves” over and over, proving nothing other than extended bouts of introspection that didn’t serve Seger well at all as a songwriter. Even so, it’s not unfair to say that even with his aggravatingly erratic output, the best of Seger’s work in a spotty career surpasses Springsteen’s consistently middle-brow rhyme scheming.

Seger did write “Hollywood Nights” in what sounds like a deliberate attempt to write in Springsteen’s drive-all-night style, and it displays Seger’s fatal flaw of trying to write in a voice other than his own. It sounds like The Boss, and likewise sounds crammed with so much pop-culture mythos that it winds up being mush-mouthed like Springsteen’s grander attempts at significance.

Springsteen, though, has fared better when he pares back his excess and gives us some tub-thumping rock ‘n’ roll; “Born in the USA” is a great song because it works on a strong backbone of a relentless beat, and The Boss sounds righteously pissed off. Seger’s epochal “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man” is the model for this, and I’ve no doubt that other Seger songs, including “East Side Story,” “Persecution Smith,” and “2+2=?” were on Springsteen’s mind when it came time for him to write a song that was topical and angry. Seger hasn’t been the most consistent songwriter of all time, but his best work—and there’s a lot of it—easily bests Springsteen’s work for economy, punch, and grit. Seger has often equaled the genius of rock ‘n’ roll masters Chuck Berry and John Fogarty in writing, which constitutes the life pulse of rock—short songs, spiked and fine-tuned rage in the lyrics, and credible, riveting beats to make the two or three minutes memorable, cathartic, and infinitely re-playable.

Seger’s strength as a lyricist is that he’s not introspective and that what he has to say isn’t hindered with club-fingered attempts at metaphor; unfortunately, Seger attempts poetry repeatedly, with laughable results, but his ability to recover these gaffes places him over Springsteen, who has not reined in his grating habits of poet-speak. Springsteen takes too many paragraphs to say “ouch.” Each of his songs, rockers, and ballads are notable for their lack of padding, musical filigree—there are no footprints of “grand music” here—and, lyrically, they are keen examples of the sort of lyrics Seger writes best and effectively—straight talk, unmarred by any reach for metaphysical density, in a voice that is something along the lines of what William Carlos Williams had in mind when he spoke of the American voice. Again, I’ve already spoken to Seger’s faults and inconsistencies as an artist (bloat and bad poesy have visited his muse more often than I care to admit). But he’s been superb much more of the time in his four-decade career, and his best work trumps Springsteen’s output. His best songs show a man that is able at times able to communicate poetically, that is to say sparingly, in plain speech, without the burden of ineffective simile or undirected allusion, the feeling of being alone in the middle of the night—intensely if diffusely—reflecting on the past, growing up awkward, first love, bad decisions, temporary blessings, such as he does in “Night Moves.” What might have been an opera for other writers, what might have been an overstuffed couch of dime store pathos is instead a soft, drifting reflection, atmospheric rather than dramatically self-proclaiming. With its caressing acoustic guitar and Seger’s splendidly bittersweet, whispery husk of a voice, the song is a meditative pause in a life, a moment of fleeting Zen, an intake of breath that is held and released in an audible sigh. There are no conclusions or resolutions, just the sense that the narrator then finds some kind of restful sleep and then arises again in the morning to shave, shower, and go off into the world again to earn his keep.

Where the trend had been for senior rock stars to give their careers a third act, issuing albums wherein they croak their way through The Great American Songbook, graying Blue Collar Hero Bruce Springsteen goes the other way and releases an album of old folk songs, 2006’s We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions. The search for authenticity continues, and the plain-spoken Springsteen—remember when his stanzas tended to be operatic librettos of intemperate desire?—sings it plainly, clearly, simply. No swelling melodies here; no subtle segues or seducing counterpoint.

The folk album, some have said, is suitable for Bruce, as he was never a great melodist anyway when he was doing the songwriting. I’m not a huge fan of The Boss; it takes too much work to reissue the same objections, and after 20-some years of bitching and groaning, I admit to liking music he’s done. Bruce Springsteen isn’t Duke Ellington or even Burt Bacharach as a melodist, but that was never the point of his work since his sound is big, brash, and in-your-face rather than catchy, seductive, or otherwise subdued with subtler chord selection. What he celebrates is the thrill of life itself regardless of the circumstances he was born into. Springsteen emerges as rock ‘n’ roll’s premier fatalist, a citizen/artist resigned to hard knowledge that neither he nor his friends will likely transcend the working class hard scrabble. Accepting what at one point seemed to be his fate, his songs celebrate the fact that he was breathing at all, that he had senses to be stimulated, and that he was going to fill his senses with cars, women, music, and racing down empty roads. For Springsteen, it seems, every sensation of being alive, from celebration to catastrophe, were experiences to be grasped and felt deeply, not unlike Kerouac. Bruce wanted more life, more sensation, more reason to live intensely as he raged and to brood deeper in the gloomier moments than any other working musicians. It could be said that he was a sensation junkie who wanted to cram it all into a single expression, a habit that made much the music unwieldy, overlong, overcooked. His music is equal parts rhythm and blues, Phil Spector, British Invasion, and folk rock, with generous portions of Kerouac, Dylan, and a wee tram of Whitman stirred into the mix. For the sort of blue-collar exhorting he does about love, death, being broke, and struggling for a better future, Springsteen’s melodies are exactly as they need to be at their best, they work as well as anything a popular pop-poet has managed to do.

When his work is crafted, sufficiently edited, and shaped, he’s easily as good as Dylan as a melodist, the equal of Seger, the equal of John Lennon. I have found too much of his music overworked, grandiose, and cluttered with the kind of business indicative of someone who hasn’t found the central theme of what they’re writing about. We see this in poets who compose at length, leaving no trace of a parse-able idea behind them, and one can witness it as well in novelists such as Franzen and D.F. Wallace, who don’t have it in them to cut away the excess so the art may show. Springsteen has this problem as well, a habit of overwriting; the effect in his longer, louder pieces tend to be a little Maileresque, circa mid- to late-sixties, where he keeps preparing to say something profound and yet the message is deferred. I prefer the punchier, grabbier, riff-based rockers he puts forth, or the terser, grainier ballads. The big band material he comes up sinks as fast as any Jethro Tull concept album has in the past. It’s about songs, not the arrangements.

Springsteen singing old folk songs and protest songs doesn’t interest me in the least, although it might be a means for him to ease into writing decent material for his next great period. Dylan landed into a profound late period, as did the Stones and certainly the quizzical Neil Young. Bruce would be a dandy addition to the grand pantheon of old guys. Productivity isn’t, by default, a desirable trait. Talented artists can dilute their impact and lessen the esteem they’ve held in with the rapid issuing of mediocre, substandard, or half-baked albums. Costello and Dylan are prime examples of this, although both songwriters frequently rebound with strong albums after some artistic lagging. There’s an appeal for artists who aren’t in a hurry to release product; I am a fan of Paul Simon’s post Simon and Garfunkel career. Tellingly, Simon released new work at a snail’s pace over the last 30-plus years; he’s a careful writer, and his body of work is therefore rich with strong, moving, intelligently evolving music. His musical ideas work often. The same may be said for Steely Dan, a band I’ve always admired for their consistent excellence in melody, production, oddball melodies, and especially well-crafted lyrics. Being slow to release albums of late places Springsteen in honorable company.