Featured Stories

Anatomy of a Folk Song: Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down

Whose Deal Is It?

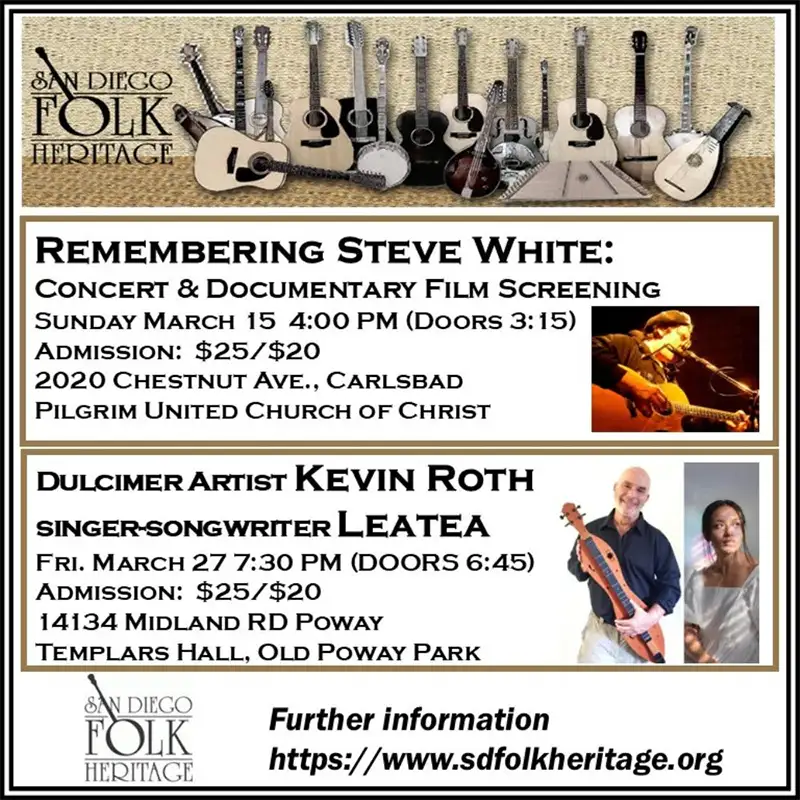

As a songwriter, I am intrigued by what makes a song memorable. Out of all the songs that have ever been sung, why are a handful still being sung generations later? Wouldn’t it be fun to dig into some songs that have endured? Let’s do it! Here’s one called Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down. Like so many classic folk songs, its origins are lost in the mists of time; its first known recording was by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers, in 1925.

The song has gone by other names (The Deal, Deal Rag, and more), and has been recorded by many acts through the years, notably Doc Watson, Flatt & Scruggs, New Lost City Ramblers, David Bromberg, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and Bob Wills (instrumental version). The subject of the song and its structure are flexible enough that singers have performed it with a diverse collection of lyrics, both traditional and original.

Poole Was Cool

Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues was Charlie Poole’s first commercial recording, and sold over 100,000 copies, a huge number for the time. (Unfortunately for him, Charlie was paid per song recorded, not per copy sold!) The verses relate to the traveling musician life and the girl left behind. The chorus brings in the “deal,” presumably referring to gambling at cards. An online search uncovers discussions of what now-forgotten card game might involve someone’s deal going down.

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Down to Memphis, Tennessee

Any old place I hang my hat

Looks like home to me

Now I left my little girl crying

Standing in the door

Throwed her arms around my neck

Saying ‘Honey, don’t you go’

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Done most everything

I’ve played cards with the King and the Queen

Discard the ace and the ten

Chorus

Oh it’s don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Before my last gold dollar is gone

Now where did you get them high top shoes?

Dress you wear so fine?

Got my shoes from a railroad man

And my dress from a driver in the mine

Who’s gonna shoe your pretty white feet?

Who’s gonna glove your hand?

Who’s gonna kiss your lily white cheeks?

Who’s gonna be your man?

Now Papa may shoe my pretty white feet

Mama can glove my hand

She can kiss my lily white cheeks

‘Til you come back again

Charlie Poole gave us a lot besides this song. He may be the original gangster of hillbilly music, creating a template for the country music outlaws since. Based in the Piedmont area of Virginia between the world wars, when he wasn’t a banjo-playing band leader, he was a mill worker, baseball player, and moonshiner. At all times, he was known as a hard-drinking carouser. He had a successful, if not overly lucrative, recording and performing career before drinking himself to death before the age of 40.

His 60 or so recorded songs include enduring folk classics such as “Sweet Sunny South,” “Only Old and in the Way,” “Hesitation Blues,” and “You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me You can find these online or in the San Diego County library on a couple of great CD collections: You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music, which includes original recordings and modern interpretations, and the Grammy-winning labor of love by Loudon Wainwright III High Wide & Handsome: The Charlie Poole Project. Both have extensive booklets.

Besides cover versions of this song, we should mention a couple songs no doubt it inspired: Deal by Garcia/Hunter and Dylan’s When the Deal Goes Down.

What’s in a Song?

Let’s look into the song–the words, melody, rhythm, and harmony or chords.

“Floating lyrics” is a term used for verses that appear across multiple folk songs. Variants of the last three verses above can be heard in a number of songs, including “He’s Gone Away,” “The Storms Are on the Ocean,” “Who’s Going to Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet” (Woody Guthrie), “Hop High My Lula Gal,” and even the classic “John Henry.”

Charlie Poole played the song up-tempo with quite a bit of bouncy syncopation, and others have found it adaptable enough for their own purposes.

The structure of the song is your typical verse-chorus A-B repetition, or sometimes A-A-B or A-A-A-B. Each of the two couplets of the verse has essentially the same melody, and the chorus melody and chords essentially repeat those of the verse.

Charlie Poole’s melody was striking, consisting of an almost immediate jump up of a full octave, e.g., on “around” in the first line, and the first and third “deal” of the chorus. (We find a similar jump in the opening notes of “Little Maggie.”) Other folks have successfully adapted less vocally challenging melodies over the chords used by Poole.

So, if the verses and melody are fluid, the chorus ambiguous, and the rhythm is not especially distinctive, what makes this such an enduring song? I contend that the powerful chord progression is largely responsible.

Ch-Ch-Changes

The song has a four-chord progression that repeats twice in the verse and twice in the chorus. In Roman numeral notation, the progression is: VI—II—V—I

Poole played it in G (always a good key for the five-string banjo!), so the chords are E-A-D-G. In the key of C it would be A-D-G-C.

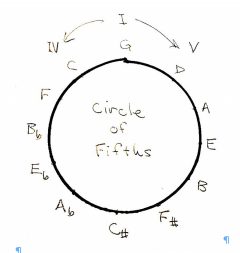

If you’ve played or studied music for a while, you might recognize this as a circle of fifths (or circle of fourths) progression. Let’s digress on that for a minute. If you want more on this subject, there is a wealth of online discussion, a lot of it using words not in my vocabulary. Simply, “I” (the “one” chord) represents the tonic, or key of the song, in this case G. If we go to the fifth note of the G scale and take the resulting chord, “V,” it is D. The V chord of D is A, and the V of A is E. If we continue this process, we eventually get back to G, having traversed all of the chords based on the 12 tones we use in our music. The cycle of fifths!

It turns out, as D is the V chord of G, G is the IV chord of D. So, if we take the same sequence in the other direction, we travel the circle of fourths. In the figure, the chord one removed clockwise is the V (D chord is V in the key of G); one removed counter-clockwise is the IV (C is the IV of G.)

The two chords most closely related to the tonic are the two adjacent ones on the circle of fifths, the IV and V (four and five), based on the fourth and fifth notes of the main scale. (These three chords include all the notes of the main scale, and many folk songs don’t go beyond them. Perhaps you’ve heard reference to a “one-four-five” song, indicating use of only these basic chords.)

For acoustic and psychological reasons beyond the scope of this article (whew!), the V chord creates some tension in the listener, which tends to resolve when followed by the I (tonic) chord. Many, many, many songs use V-I as the last two chords for this reason: it just feels settling.

So, let’s look at the progression in Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down. E-A-D-G. Each one of these is a relative V-I transition. So, rather than a single resolution at the end, we get three! (E-A, A-D, D-G, are all V-I.) Three for the price of one! I believe this is a large part of the subconscious appeal of this song. Plus, at the start of each sequence, we get a transition from the G-E (I-VI), which is dramatic and relatively (no pun intended) uncommon in folk music.

Go Ask Alice

It’s interesting to note this progression is part of the more involved sequence used in “Alice’s Restaurant,” among others. Perhaps we’ll take up that in a later column.

In the meantime, I’ve put together a little video of playing “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” in the key of E on guitar. Sing along if you like! https://youtu.be/pd13-5in7jc