Featured Stories

James Long: His San Diego Musical Roots Stretch Across the Pond

I left San Diego 1963; I was drafted into the armed services. (The Vietnam war was just in its beginning stages.) In 1963, San Diego was a “naval officers’ retirement town,” so to speak. There wasn’t much jazz. The little jazz that was there, we nourished it. When I returned, things had changed quite a bit. I wasn’t on the jazz scene as often as I would have liked. I got married; we had a child. Most of my gigs were of a commercial nature in order to earn money for our family. The jazz scene progressed with me, more or less, in the background.

I was born September 28, 1940. I have a sister, Marlene, who is four years my senior. My mom, I am told, took piano lessons before I was born from a man named Benjamin Franklin Locke. When Marlene got old enough, she also took lessons from him. When I was old enough (six years) I took lessons from him also until I was 16 or 17 years old. I am told he gave me the last lesson he ever taught—he went home and passed away somewhere in his 80s.

Thus, my first instrument was piano. (By the way, my father’s idea of good music was a bloodhound chasing a rabbit! Otherwise, the only other thing he considered music was Mahalia Jackson singing “Silent Night.”)

I attended Sherman Elementary School, and in those days when you were in 4th grade you were allowed to be in the school music program. I started the violin in 4th grade at the age of nine. The teacher, Mr. Perret, (or at least this is how it sounded) traveled from school to school giving instrumental music lessons. (I eventually did the same thing for the El Centro Elementary School District.)

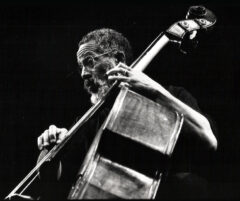

I played violin (and took private lessons) until my 16th year. I always was fascinated sitting in the violin section at how when the basses joined the composition; that was when the “real music” began. So, one day in summer school orchestra (I always went to summer school; I couldn’t get enough) our teacher, Richard Braun (bassoonist in the San Diego Symphony), said we need more basses in the orchestra, who wants to play the bass? I raised my hand. I stood up and took the bass in my hands, fully aware of how much larger it was than my violin, and Mr. Braun said, “This is B flat, James (he put my first finger on the “A” string). “You are a violin player—you can figure out the rest,” and it was “off we go into the wild blue yonder!”

My family came from a Southern Baptist background. But when my sister had some problems in the public school environment, my parents sent her to a Catholic school, knowing that the education system was excellent there. The sisters loved Marlene: they discovered that she was very, very intelligent and determined. Marlene, of course, loved the sisters, also. My sister did so well at the Catholic school that my parents decided to send me there. It is there at Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic School I met my soon-to-be best friend Benny Hollman (that is another chapter of a book).

My sister was so inspired by the sisters that she became, much to my mother’s dismay, Catholic. Not only that, she went to medical school, became a doctor, and thereafter a nun in the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary Order. I call her the “true Protestant” of the family because she went the other way around!

I left Our Lady of Guadalupe mainly because my mother saw that there was no real music program there.

SCHOOL AND MILITARY BANDS

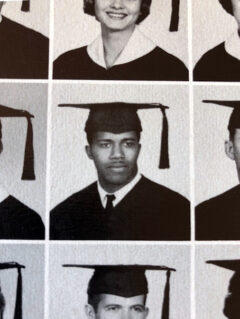

The first time I remember seeing Bob Magnusson, he was playing French horn in the Youth Symphony Orchestra. He was so young that his feet didn’t reach the ground at that time. I am sure that he was absolutely the youngest member. I was the oldest at 17 or 18. Bob’s father was my orchestra teacher in summer school at San Diego High School when I played violin. I graduated in 1958 and attended San Diego State College. During my last years of high school, I also took piano lessons from Adam Cato, an acquaintance of Art Tatum. Adam Cato was an excellent jazz pianist; he helped me develop my technique. He only taught me classical music, saying that at that point, “It was better for my pianistic development.” Preston Coleman, an excellent bassist and guitarist, also taught me a lot about substitution chords and alternative harmonies.

In my high school days I played in a rock ‘n’ roll band called the Velvetones, led by Raymond Rios and later Benny Hollman. There were several other bands like ours. One was led by my good friend George Semper. Arthur Blythe also played in a rock band. He and I would jam at my house sometimes. He made a name on the music scene later and was known as “Black Arthur” Blythe.

When I was at San Diego State College studying to become a music teacher, if you played one jazz lick you were kicked out of school.

After a couple of years, Dr. David Ward-Steinman came to teach there and things changed, thank goodness. He was a known composer. Being of “status” he was allowed to do “modern” things. We even had a little jazz ensemble in which he participated and led. Jim Plank was the drummer. (The last time I saw Jim, he was about 23 years old.) I don’t think we were allowed to use the Music Department rooms, we were somewhere else on campus. I remember that trumpeter Charlie Caudle also participated.

Mike Wofford use to come and play piano in the music building late at night when the other professors were not there. I think Mike was a business major then. Some years later, Jimmy Noone Jr. even gave jazz history courses there.

I graduated in June of 1963. JFK spoke at our graduation, unannounced. It was like an impossible dream. The next day, I boarded a plane to Washington, D.C., to see my sister, Marlene, graduate from medical school. It was a special year.

I taught music for the entire El Centro Elementary School District as a traveling teacher. Hotter than heck. You had to hold your steering wheel with a handkerchief. If you had a flat tire, you had to wait until the sun went down before you could touch it. It was 100° F at midnight—but I have never seen anything more beautiful and special than a desert.

After a year of teaching, I was drafted into the U.S. Army. I was chosen to be a chaplain’s assistant because I could play the piano and sing all the hymns. Then some officers in the Army band heard that I could play piano and bass also. They pulled some strings and I was in the Army band, mainly to play gigs with the officers in the band who were gigging everywhere and making extra money. (I don’t know how they were able to get around the chaplain; chaplains and doctors had the final word in the Army.) The only catch was that I had to play a band instrument. Usually piano players play the glockenspiel, but that post was already taken. I had a choice, play the flute (oh my, too many notes!) or play the tuba. I chose the tuba. At San Diego State, when you become a general music teacher, you had to be able to give lessons on all the instruments. Consequently, I had to learn the flute, clarinet, oboe, trumpet, French horn, trombone, tuba, snare drum, and two of the string instruments. So, I was actually a beginning (more or less) tuba player in the training band. (I said playing the tuba is better than going to Vietnam with a rifle in your hand!)

I played many gigs with the officers of the band, where I got a chance to gig with Bing Crosby at the house of Alexander Graham Bell’s granddaughter. I also played in the Carmel Symphony Orchestra while stationed at Fort Ord, and then some orders came down from above: they needed a tuba player in the 3rd Infantry Division Army Band in Wurzburg—and off to West Germany I went.

We boarded the boat in New York Harbor (the first and last time I have ever seen the Statue of Liberty) with a couple of thousand other soldiers and passengers (we soldiers slept below the decks)—and as the boat pulled away from the dock, there was an Army band playing for our departure. I looked at the band and looked right into the eyes of Benny Hollman, an emotional moment! (Later, after our tours of duty, Benny told me that drummer Billy Cobham was standing next to him in that band.)

On the boat I was singled out to play piano and sing for the church services. Luckily for me, again—because everybody had to rise and shine at 6 a.m., but I was allowed to sleep as long as I wanted to; I just had to be on time for services at 9 or 10 a.m. (I am not really a singer, but at least when I sing in church I am forgiven, I hope.)

Once in Germany, I was a tuba player. All the other tuba players had more experience than I. I had only been playing for about six months plus the few months of training I had at San Diego State College (thanks to Mr. Millard Biggs, the French horn and brass teacher. Mr. Biggs’ son, Gunnar, became, I understand, an excellent bassist). In this Army band the leader of the section would always give me the ugly eye. What is interesting about my position is that I was the only one who completed the job description because I also played string bass, and the others did not. Being the only bonafide bassist in the section, I was left alone. This band went to Holland to play for a special festival called The Four-Days Walk. It was there I met my wife-to-be, Marjanne, so I am writing all of this from Holland because I played tuba in an Army marching band! (And at the time the tuba was broken—I was told just to fake it because there had to be a whole rank of tubas to make things look right.)

Also in this period I had my first official bass lesson. Before this, I was more or less self-taught—but I did play the violin, so strings were no strangers. This lesson was at the Wurzburg Conservatorium. My teacher, Professor Reuschell, told me he was casually flying a plane over France in 1943 and, apparently for no reason at all, they shot him down! Of course, we know the real story was that he was flying a bomber for the Germans during the Second World War. He was a great teacher. He promised me a job in a European symphony orchestra if I would complete my study with him, but I got involved in so many other things and I wanted to go home at one point.

One day with the band, I sat down and played the piano and my whole Army career took another turn. I started gigging with the officers and other band members. Notable players were Clifford Thornton and Joe McPhee, who have made a mark of their own in the free-music sector. Also there was LeRoy Flemming, who later, after the Army, played with Joe Tex and had just became a baritone sax player for Otis Redding and fortunately missed the plane that went down, killing Redding and the others.

While I was still in the Army band I was discovered by a special entertainment unit called the 3rd Infantry Division Glee Club. It was also the favorite group of the general. Some more strings were pulled, and I left the band for the glee club. The glee club did not even have to wear an Army uniform. We got up at 8 or 9 a.m., put on our suits, ate breakfast at the Army cafe, drank coffee, did crossword puzzles, and at 10 a.m. went to the music room and sang for a couple of hours. I was the pianist and bassist for the group (and also sang).

We had a better job than the officers! They had to get up at 5:30 a.m. to inspect the troops. All the rest of the Army guys disliked us (of course). They called us “the damn tweetie birds.” In the Glee Club there were two very fine musicians: a drummer named Gary Stoloff and guitarist Phil Upchurch. I don’t know what ever happened to Gary but, as you probably know, Phil Upchurch was the “other” guitarist in the George Benson band, played guitar for Ramsey Lewis, bass guitar for Donny Hathaway, and for many, many others.

After the glee club, my two-year hitch was up and I returned to the States.

RETURN TO SAN DIEGO

I was substitute teaching at Madison High School for a few months. I sent for Marjanne, and we got married. In the first few years of our marriage, I taught at two junior high schools—O’Farrell Junior High and Bell Junior High. You know, like most (jazz) musicians I had to have “a gig and a hustle.”

I also took lessons from Fritz Hughart, a wonderful teacher, a wonderful bassist and a wonderful, along with his wife, Annette, human being.

When I came back to San Diego, there were new names and faces. One of these names was Butch Lacy; he was the piano player in our Calvin Jackson Big Band. I remember he would really be sweating it out playing Calvin’s charts. At the end of a piece, Calvin would say (not all of the time) to the pianist, “I guess you’ll have to go home and practice this one,” and the poor pianist would be standing there as if he were trying to find a rock to hide under. I am glad that I was only the bass player. I remember that when you would mess up a passage or bumble a part, Calvin would come up to you and pull on your shirt at shoulder level as if he were pulling your stripes off of your uniform and taking you decorations away. Calvin had a funny sense of humor.

Calvin was one of the most brilliant musicians I have ever met. I used to play gigs with him, just bass and piano. He would flip out a bass part of one of his arrangements at a gig with a bunch of terribly high notes and difficult reading passages for a bass player. I would say “Calvin, I will have to study on this at home before I can play it,” and Calvin would say “I had a girl (with emphasis on girl) in New York who could sight read this.”

Even though he would put me through the paces, he was a wonderful and sweet guy. He would come to my house and we would play together. He must have been pretty capable to be the assistant arranger at MGM Studios. He told me once that he got an award for writing or arranging the score for The Unsinkable Molly Brown movie or stage musical. There was also a movie made about and with him comparing writing, arranging, and composing with the realization of architectural structures. I know this for sure because I have seen it on PBS years ago.

I also played at the San Diego County Fair on the Del Mar Fairgrounds in the Del Mar Fair Band under the leadership of Phil Strak. We backed up Lou Rawls, the Mills Brothers, and others. Tony Higgins, my high school orchestra teacher, was a woodwind player in that band. There was a wonderful guitarist whose name was Walt Namuth who is said to have been a guitarist in the pop group the Mamas and the Papas. The same band backed up Jimmy Durante on occasion.

There were people, like myself, who had a regular job and played gigs—like the chiropractor Larry Tain on trumpet. Dentist Charles Hammond, piano. Dentist Dr. Bill Hunter, piano. Policeman Frank Weibel went to Juilliard and played piano.

Then there were the guys who were stationed in the Navy who were an important part of the jazz scene, like Leroy Locke, tenor sax. Carl Evans Sr., all woodwinds (his son was Carl Evans Jr.). The first jazz solo I ever heard played on the tuba was by a Navy guy named Jerry Scheff, who later became the bass player for Elvis Presley.

There was Bill Mays, who called himself Willie Mays then (probably because that was his name). My father would ask him when Bill would call the house, “How many home runs have you hit today?” My Dad always got a big kick out of that. Then there was Ted Williams (another famous baseball name from then). Ted could play touch bass with his left hand, drums with his right hand and feet, and sing like hell. He was a brilliant musician. He stopped playing at one point, went to Wyoming (or somewhere) and broke horses for a living—a bronco buster, I am told.

Clark Gault played valve trombone with his right hand, piano with his left. He was a great arranger. We won a big band contest where Pete Jolly was one of the judges, and another was a heavyweight from the Lighthouse Allstars.

I was in the first Chargers Band under the leadership of Angel Martinez. Soon afterward, it was taken over by Benny Hollman, then my best friend and best man at my wedding. Angel Martinez also had an Across the Border Band with some musicians in Tijuana. The Tijuana chief of police was in it, and the head of the fire department played first alto. It was a great band. Some people had the tendency to look down on our southern neighbors—but these guys were well trained; they could sing everything they played in solfège!

There was Danny Acenas on trumpet. He went to Las Vegas. Sadly, he has left us. His brother was Leo Acenas. Talented bassist Hank Dobbs disappeared into thin air, it seems. Pianist Barney McClure lives now in Washington State and was also the mayor of Yakima City, I believe. Paul Gormley was an excellent bassist. He went to Las Vegas. In those days, Eugene Watson and Maurice Stewart both played piano. There is an excellent pianist and bassist, Richard James, who is still active in San Diego. Ronnie Ogden played drums. Bob Dowd played drums (he became a practicing physician). I don’t know what ever happened to these fine musicians.

Leon Pettis, Manzo Hill, probably Nat Fuget or Preston Coleman on bass, and myself provided the music for the Bob Dale Show then. Manzo Hill was a brilliant alto sax player who became an electric bassist later.

Teddy Picou played tenor sax. Jimmy Noone Jr., was the son of the New Orleans clarinetist Jimmy Noone. On the first gig I ever played with him, he played upright bass also. He also played organ but was primarily known for his saxophone playing. Charles Owens, who eventually went to L.A., taught me my first jazz tune, “Night in Tunisia,” on piano and on bass. Preston Coleman was playing bass. Mark Dresser, the bassist, and I hooked up when he came to Rotterdam playing with trombonist Ray Anderson. Frank Strong played trombone. There is Dwight Stone, trombone, one of my dear friends from the class of 1958 and beyond also, at San Diego State College.

There is Tony Higgins, my high school music teacher who played tenor sax in a Bill Perkins style; Larry Honing played bass.

The bass player for Cannonball Adderley was Victor Gaskin. He, like many others, came from somewhere else and settled in San Diego. I remember we had a group together (before he was with Cannonball) that would rehearse at night in the San Diego State music department. Victor would come to the room, sit down and clean his fingers and fingernails before he would touch his bass. He was then a full-time automobile mechanic.

SETTLING IN EUROPE

After five years of being back in the States (our son Roma was born during that period), we moved to Holland in 1972.

My wife wanted to go back home, and I was also open for a new experience. I figured I would be a full-time musician—but instead I became a grammar school (children from three years of age) through high school music teacher and gigged whenever I could. That was a lot and often, to the point that my wife and son had to slow me down.

I was so busy in that period, at one point I taught at three different schools part-time and played in 10 different bands. For a period, I would teach at the American International School of Rotterdam from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m., go grab a bite at home or elsewhere, and then head to the south of Holland (Holland is a very small country) 30 miles from Rotterdam and teach from 6 p.m. until 10 p.m., go home, grab my bass and play a gig in an after-hours jazz club from 11 p.m. until 3 a.m. the next morning, then be at the school again at 10 a.m.!

It was at this point my wife and son had to slow me down.

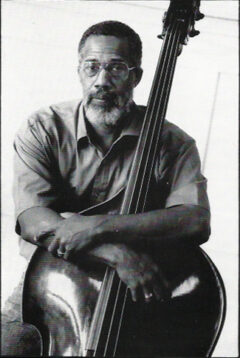

In these years I played at many venues with many people. I was the bassist in a trio of very fine Dutch musicians (Cees Slinger piano and John Engels drums) that accompanied many musicians, a lot of them very, very talented Dutch musicians and also internationally known artists. I did tours with Jimmy Knepper (trombone), Lew Tabackin (sax/flute), Woody Shaw (trumpet), and Johnny Griffin (tenor sax). I performed at the North Sea Jazz Festival in The Hague with Jon Faddis (trumpet) and Bob Brookmeyer (valve trombone). I played other gigs with Max Roach (drums), Alvin Queen (drums), Bruno Castelluci (drums), Scott Hamilton (tenor sax), Teddy Edwards (tenor sax), and Bud Shank (sax/flute). One of my biggest thrills was being able to play with James Moody (tenor sax) as he sang “Moody’s Mood for Love.”

I recorded a CD titled Solar with Don Bennett (piano) and Doug Sides (drums). I also made a record with Clifford Jordan (tenor sax) and “Philly” Joe Jones (drums) titled The Rotterdam Session. This record, for some reason, “got lost” and for a while was a collector’s item. I understand that it might be re-released soon. I am the only living member of that trio.

I also played piano in the band of my dear wife, Marjanne, who was the leader and vocalist. In 1992 there was a special celebration in honor of me being prominent on the jazz scene in Rotterdam for 20 years. Johnny Griffin and Mark Lewis, the leader of the band in which I was the regular bassist, participated in this celebration. My son, Roma James Long, also participated on the bass guitar.

It was in the early 1980s that I connected with Mark Lewis. It was a band where you could find your own personal sound, voice, or purpose with the music. A CD featuring the Mark Lewis Quartet titled Naked Animals, recorded 30 years ago, was just released in 2021.

I’m retired now, still in Holland, but in touch with my friends in San Diego.

This interview was conducted as part of the research into a forthcoming history of jazz in San Diego by Jim Trageser and Michael J. Williams.