Featured Stories

Gospel: From Africa to the Rest of the World, the Sound of Joy and Hope

Golden Gate Quartet

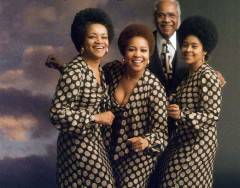

The Staples Singers

It’s unmistakable. The sound is full and lively. And American as apple pie. Whether you’ve been in the pews on Sunday morning or heard the voices of a choir drifting out of the windows of a church or heard its stamp on the voices of Aretha Franklin, Lou Rawls, James Brown, and other soul stars, you’ve heard gospel music.

Traditional scholarship traced the roots of gospel music to Europe, finding the basic song forms and scales used in more than 90 percent of gospel as having its antecedents in songs and musical forms from the European continent. More recent and stringent research has turned this thinking on its head, tracing the music of gospel to Africa. Additionally, Africa contained and continues to hold the mixture of music, religion, and world view necessary for gospel music.

At the time of the first Portuguese and Arab explorers to the west coast of Africa in the 1500s the explorers found a patchwork of organized kingdoms, such as the Wolof States and Asante Empire, and smaller bands of hunter-gatherers. Cultures differed, but there was a commonality of music and dance. And as well, unlike Europe — in which there has been a distinction between music and the body — in Africa there was no separation of music and dance. And for Africans music was inseparable from life. The African concept of music is egalitarian and communal. Concerts by skilled musicians performed to passive audiences are rare in Africa. Everybody sings, and one voice is not thought to be more beautiful than the next. Music is also more bound up in the details of daily living than in Europe. There is also no line drawn between sacred and secular, because all is sacred and all secular. The explorers also noted that lyrics to songs were often improvised, as they are currently with gospel music.

Perhaps the most distinctive influences from Africa on gospel are the “hot” rhythms or polyrhythms employed in African music. European music is characterized by the dominance of a single rhythm, all the instruments or voices adhering to the same beat. African music has accents falling between the down and upbeats. This results in temporal displacement of melodic phrase. To get an idea of the difference, sing “Tea for Two” as an example of a song of European heritage, and “Oh Happy Day” as an example of gospel. While you can feel the rhythm in the former, it’s a lot more fun to tap your toe the latter.

Other aspects of African music found in gospel are alternation of verse and chorus, the use of short musical phrases, a call-and-response format, lyrics with secondary meaning, and improvisation, both lyrically and musically.

Gospel is primarily music of the church, but, ironically, the conversion of slaves to Christianity seems to be one of slow assimilation, rather than one of directed evangelism on the part of white Christians. For the most part, white Christians thought black slaves and freepersons inferior and unworthy of the saving powers of Jesus. Also, the antebellum South seems to be a place in which religiosity of any sort was not a strong part of the culture. Church attendance was not especially valued. Visitors to the South also remarked on the dearth of bibles in southern states.

Though there were spirituals based on Christian New Testament subjects and themes, the larger emphasis was placed on the Christian Old Testament. This is due, in part, to the South being a land of Protestant denominations, which emphasize a Manichean worldview principally based on the Old Testament. Slaves also identified with the story of Exodus, a people freed from bondage in Africa. Howard Thurman recalls in his book Deep River and the Negro Spiritual Speaks of Life and Death how his grandmother, a former slave, forbade him to read from Paul’s Epistles, because when she was on the plantation the local white minister would preach to the slaves with the quote of Paul, “Slaves, be obedient to your masters.”

Long before the American Civil War, the African-American musical form that can be identified as the spiritual took shape. The first mention of spirituals in print goes back to December of 1865, when W.F. Allen, in his article “The Negro Dialect,” published in Nation, mentions “sperituals” and “running sperichils.” Of course, there aren’t any recordings of this music, and even the most extensive research of this music has found only fragmentary descriptions of the way it sounded. Needless to say, many white clergy and missionaries described it as “idolatrous.”

We do get a general outline of the spiritual, that their primary melodic modes were based on the pentatonic scale. At this time there is the identification of the indeterminate third or the “blue” note of the flattened third as well as the flattened seventh. You are probably most familiar with the use of these notes in the blues. Composer W.C. Handy described these notes as giving music a “curious groping tonality” and a “scooping swooping slurring tone.” He identified these notes as evidence of African origins of spirituals and blues.

Spirituals were not sung in unison. Nor was a system of polyphony used. It is best to describe the singers’ approach as one of heterophony, where slaves followed the lead melody for the most part, but allowed themselves to wander away from it as well. Spirituals incorporated the clapping of hands and stomping of feet. Spirituals are congregational and more “organic” than gospel, created and continued orally from worship service to worship service. Gospel has more of an emphasis on artistry and performance. While spirituals emphasized sorrows and suffering, gospels were written with the intent of uplifting people, particularly during the Great Depression.

By the 1930s both blacks and whites had begun to call some music as gospel to differentiate it from older hymns. Older jubilee-style singing, which emphasized harmony over improvisation and rhythm, still dominated the music of church and black performances. Some groups performed in both styles, and some older jubilee songs were transformed into gospel. This was also the time when great gospel singers, such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Mahalia Jackson distinguished themselves and put their personal mark on gospel. Beside choirs, the 1930s saw the rise of the Sensational Nightingales and other gospel quartets.

To get an idea of the difference between jubilee and gospel, there is a YouTube video of the Golden Gate Quartet singing a jubilee of “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho.” The harmonies are tight and the performance is, though lively, relatively restrained when compared to the high-spirited gospel “Somewhere to Lay My Head,” by the Sensational Nightingales (also on YouTube). With the Nightingales, hands clap during a call and response. The “lead” singing is improvisational with a voice that is not traditionally “beautiful” but more like what we have grown used to with blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

Gospel’s popularity waned somewhat in the fifties and sixties. The purely a cappella quartet became rarer, too. The electric bass more or less replaced the function of the bass vocalist, and there was more accompaniment with other instruments, too. The sound of gospel made its way into popular song and performance, with several performers, notably Sam Cooke and Lou Rawls, transitioning to the new music called soul. Some performers, such as Aretha Franklin and the Staple Singers, moved back and forth from performing gospel to popular music.

Besides directing the Martin Luther King Junior Community Choir, Ken Anderson has been the director of the gospel choir at UCSD for the last 24 years. “We do it all. We sing spirituals, gospel, and anthems,” he says. Anderson explains that anthems are more classically oriented than spirituals or gospel music.

In his years as a music director, Anderson has seen gospel music going worldwide. “I do workshops in Denmark two or three times a year,” he says. He lists some of the other countries where he goes to teach gospel: Poland Norway, Sweden, Italy, Czech Republic, the Philippines, and Japan. “The groups over there are very much into gospel. These are trained musicians as well as those wanting an experience of gospel.”

He teaches trained and untrained musicians in the same manner. “The music is not written down,” he says. “Singers learn their parts by rote. Someone will sing a song and the person sings it back. And you don’t have to be a good singer to create a good sound. As a matter of fact, the sound of gospel relies on that bit of untrained musicality. With gospel you’re not aiming for uniformity.”

Anderson says that the overseas choirs sound every bit as authentic as the African-American gospel choirs, with all the hand clapping and enthusiasm. Emphasizing that anyone can sing gospel, he tells the story of an exchange student from Australia who had never heard gospel but joined the UCSD choir out of curiosity. That student became the choir’s featured soloist, even wowing all-black audiences.

Stacey Murray, who just recently joined the Martin Luther King Junior Community Choir, has been singing gospel in church since the age or three. “My mother put me on stage to sing a song,” she recalls. “Right then the choir director said that normally they don’t take on folks so young, but he wanted me in the choir.” In high school Murray sang popular tunes in the school choir. “But with gospel you get into it. You have more freedom to sing. The melody is more vibrant. With gospel I get that inner feeling of music. It touches me on the inside.”

Unless otherwise noted, the information used in this article came from People Get Ready! A New History of Black Gospel Music by Robert Darden, published by Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004.