Featured Stories

Charles McPherson: Weathering the Pandemic with New Album and Ballet Project

As with all of us, veteran alto saxophonist and longtime San Diegan Charles McPherson has seen the ongoing pandemic rearrange his routines in ways neither anticipated nor particularly welcome.

“Everybody’s affected by this, of course,” the jazz icon said by phone last week. “The pandemic has really taken a toll on us: the clubs are closed. Congregating everyone in one room isn’t happening the world over. The main part of our livelihood is affected by this pandemic: no concerts at Carnegie Hall or Lincoln Center.

“For me, I have been practicing a lot—so you can try to squeeze some positiveness out of any situation. I practice more than I have in the last few years.

“I am writing and getting in the mood to write. I am teaching online.”

Despite the challenges, September will see the release of his latest recording, Jazz Dance Suites, followed by an October venture with the premier local ballet company featuring some of the material from the new album.

“The San Diego Ballet is going to try to have a season—either it will be online, or they might be able to do something live. If it happens, it will be late October. The music will be a tribute to Bird [Charlie Parker], and a repeat of ‘Song of Songs,’ one of the suites on my new CD.”

McPherson said his daughter Camille is a featured dancer in the company, and with that familial relationship he’s also become the resident composer for the Ballet. The new production will feature original McPherson material and is being choreographed by Javier Velasco. “He’s a real smart guy,” McPherson said. “Extremely talented, very multi-dimensional. He mixes classical ballet with modern.”

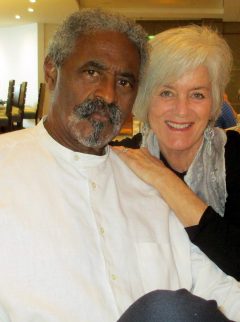

The new album is self-produced with his wife, Lynn. “We recorded it at the famous Van Gelder Studio. I think they have a beautiful sound on the recording. I’m not a real audiophile, but just on that level people are going to really like this. And the musicians are great: Jeb Patton on piano; David Wong, bass; Terrell Stafford, trumpet; Israeli guitarist Yotam Silberstein; and Lorraine Castellanos singing.” (Also on the recording are pianist Randy Porter and drummer Billy Drummond.)

“On ‘Love Dance’ Lorraine is singing in Hebrew. The whole thing is about unrequited love with King Solomon, some darkness and sadness, and unfulfilled stuff. There’s enough emotional variety to express joy and sadness; there’s enough there to put to music.”

While he’s excited about the new album and its release, McPherson is also hoping the public health situation will allow the Ballet to offer its performance live in front of an audience—he said the lack of live performances has been very difficult for him personally.

“In a live performance, the audience is giving you something back—the reaction is informing the performer in a subliminal way. That’s a magical human thing going on there.

“I love to play and perform, I just love it. If I could push a button and do only that, I would do that. I love to play the horn. I would do that all day every day.”

And even after six decades, McPherson said he’s still finding new things to put into his solos when he improvises:

“I keep looking for new melodic themes. One of the hardest things in music is to find melodic ideas that haven’t been done. That’s very hard. And you can’t teach melodicism in college but you can teach harmony. You can teach the elements and functionality of harmony. But you can’t teach the student how to take the best note, because what is the best note? That’s a much more complicated thing, to be melodic and strong and original, and not be mundane or banal. To be insightful and new—that’s hard. It’s easy to be dissonant. It’s as easy to be as dissonant as the universe can stand. It’s not easy to come up with a melodic theme that resonates in the human soul. That separates the genius from the journeyman.”

But he believes the creativity comes from working within the structures that define jazz, not in rejecting them.

“To improvise with form and structure being part of it, and you’re improvising within certain laws. To me, that’s what makes improvising fun, to have the freedom to express yourself within form and structure. Music is a wonderful phenomenon. To take tones and sounds and be able to have so much control that you can do what you want with them…. That’s a fun thing to do. It’s part of the human condition to want to be creative.

“The fact that you have to adhere to some kinds of laws—harmonic—and be free within that is the fun in it. When you play ping pong, the thing that makes it what it is is the net. The net being there and hitting it on the table is what the structure is. Within that, you can be as free and creative as you want.”

McPherson pointed out that jazz is more than just improvised solos, though; there are numerous styles of music around the world that include improvisation.

“A lot of times people think that jazz is only improvisation. See, that’s not true. The prospect of improvisation is just part of the ingredients of what jazz is. I can put country-western on and improvise. But it’s not jazz. Jazz has an identity. It’s a feel that’s different.

“All the notes are the same: a D is a D. I don’t care if Beethoven did it or Waylon Jennings; what makes it different is how it’s treated. The rhythm, the scales, the sonic identification. These things are what give any music an identity. You can say this is Middle Eastern or South American or European or African. There must be something that makes you say this is Hungarian folk music and not Chinese folk music. So, it’s the treatment.

“The old composers improvised. People like Bach would sit down and improvise for hours. Mozart could do that. That’s how he wrote—you have to realize that improvising and writing come from the same part of the brain—it’s just that when you write, you freeze it. Really, when you write a composition, it’s a frozen solo. Improvising is you didn’t freeze it, it’s just stream of consciousness. But it comes from the same part of the mind, actually.”

Which brought McPherson to another love of his, the enduring staying power of the Great American Songbook.

“The reason jazz musicians tend to like the Great American Songbook is that the people writing that music were really good musicians. The harmony is intelligently crafted by a professional, not by a talented guy who gets marketed. Nat ‘King’ Cole was a virtuoso piano player! George Gershwin almost sounded like Art Tatum. Some of these people, a lot of the composers, were Jewish composers from Eastern Europe who learned a lot of that great harmonic knowledge over there, and it’s part of the music. They were informed by people like Rachmaninoff and those composers.

“Not only that, but the lyrics are extremely intelligent, very adult, and deep. You look at the lyrics of some of those old tunes, and the lyrics are very intelligent and for mature adults—not for 15- and 16-year-old people. They’re for people who’ve been in love and know what it is. The poetry is actually really good, and the music is beautiful.

“So, jazz musicians love harmony that’s sophisticated and has a degree of complexity and deepness. We love to improvise on that! We’re improvising on tunes by people who are real musicians! I’ll play original music, which I love to do, but I’ll still play Gershwin. It’s like Bach almost.”

As to the future of jazz, McPherson is grounded in realism. His childhood was the heyday of the Swing Era, when jazz was both dance music and the popular music of the day. He came of age during the Bop era, playing with Charles Mingus as a young man. And today?

“Jazz is considered an esoteric music. It’s not America’s music—it’s born in America, nurtured in America, but it’s not accepted by the average American. It’s here and it will always probably be here. But will it ever be anything other than esoteric?

“I do know that jazz is part of the global fabric of music. It’s obvious that there’s always going to be a percentage of people where jazz resonates with them. I can go to Norway or Taiwan, and there’s going to be some tenor player trying to play ‘Giant Steps.’ However, for 95 percent of the people it doesn’t mean a damn thing.

“The only thing I can take solace in is it’s been here a long time, but I don’t know if it’s going to be a popular form. Jazz is going to be like classical music: people think it’s great, but they don’t listen to it.”