Other Expressions

You’ll Get Pie in the Sky When You Die

It’s hard to think about the history of labor unions in this country without thinking of the music that gave it its soundtrack. The American labor movement of the 20th century used powerful lyrics and catchy melodies to champion the causes of workers who voiced grievances for just wages and dignity. In 1791, the first factory, a textile mill, opened in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. The Industrial Revolution had arrived and, with it, all the miseries of capitalism, wage-slavery exploitation, and greedy owners. Many of the first labor songs were about the textile mills, like “The Factory Girl,” which was written in 1830. Some folks might think that the artists who wrote and sang these songs were obscure, little known singers hoping to one day make it to the “big time.” Well, this could not be further from the truth. Merle Travis penned the wonderful song “Sixteen Tons,” the story of a Kentucky coal miner that became one of the signature songs of Tennessee Ernie Ford (also song by Johnny Cash). Then there is Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, who helped to make famous the African-American folk song “John Henry” about a steel-driving man. Then there are tunes like Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm,” Gil Scott-Heron’s “Three Miles Down,” and Hazel Dickens’ “Fire in the Hole,” among many others. Songs about the laborers’ working conditions, hopes, and aspirations have been sung in America since slaves were brought to these shores in chains in 1619. Doing back breaking work, they sang field hollers based upon lyrics from the Old Testament. Labor songs in the early part of the twentieth century helped to pass the often monotonous hours for thousands of workers who were tenant farmers and mill workers.

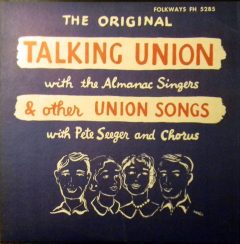

Growing up in Detroit and San Diego, I cut my teeth on labor and protest music from listening to my parents’ records. One that stands out for me was the album Talking Union by the Almanac Singers, a supergroup based in New York City and founded in 1940 by Millard Lampell, Lee Hays, Pete Seeger, and Woody Guthrie. They chose the name because Lee Hays had said: “Back home in Arkansas farmers had only two books in their houses: the Bible, to guide and prepare them for life in the next world and the Almanac, to tell them about conditions in this one.” The Almanac Singers specialized in songs that attacked fascism and racism and that were pro-union. In fact, one of the most famous photos of Woody Guthrie is where he is strumming his guitar and on the guitar was taped the words “This machine kills fascists.” The Almanacs all agreed that their purpose was to use music to aid the fight for social, political, and economic change.

I thought seriously about this when it came time to create my soundtrack for my new documentary film American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs (screening at Grassroots Oasis May 19th). I decided to incorporate some appropriate labor songs I grew up singing, as well as compose tunes in the genre of old-timey fiddle music. The soundtrack was recorded here in San Diego and features Fred Benedetti, Jeff Pekarek, Walt Richards, Elizabeth Schwartz, the Hausmann quartet, myself, and special guest, fiddler Jeremy Kittel.

Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926) was one of America’s greatest labor and union organizers at the turn of the twentieth century, who also ran for president five times for the Socialist Party, which he cofounded with Victor Berger in 1901. In the film, we hear Debs reciting a letter he wrote to Gov. William Spry who upheld the murder conviction of Joe Hill (who was executed despite only circumstantial evidence) of a grocer and his son. Joe Hill, born Joel Emmanuel Hillstrom in 1879, was a Swedish-American labor activist who moved to the United States in 1902. He became an itinerant laborer, joining the I.W.W.–Industrial Workers of the World (co-founded by Debs)–rising through its ranks, traveling, and making speeches. Joe Hill is most famous for the many wonderful poignant labor songs that are still sung around the world today. I include in my film Hill’s song “The Preacher and the Slave” (1913). Like many of his fellow I.W.W. members (Wobblies) Hill was more interested in filling an empty belly than in saving his soul. Hill wrote a parody that ridiculed the Salvation Army who preached “pie in the sky,” the reward awaiting you if you would only meekly take what an unjust situation might mete out.

Long-haired preachers come out every night,

Try to tell you what’s wrong and what’s right;

But when asked how ’bout something to eat

They will answer with voices so sweet:

CHORUS

You will eat, bye and bye,

In that glorious land above the sky;

Work and pray, live on hay,

You’ll get pie in the sky when you die.

In the film, I describe the Lawrence Textile strike of 1912 where Polish weavers–mostly women–opened their pay envelopes to find their wages had been reduced by the owners. Immediately they shouted “not enough pay” and walked off the job. Soon Italian workers (again mostly women) also found out they had been shorted their salary and they too walked off the job. By the next day, 22,000 women, men, and children had left their jobs. The walk-out became known as the “Bread and Roses” strike, based upon labor organizer/activist Rose Schneiderman’s line in a speech she gave where she said, “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.” This inspired the title of the poem written by James Oppenheim, which was then put to music by Caroline Kohslat . Since there was no common language among the workers (most spoke little to no English), singing songs became a unifying factor. “Bread and Roses” became the anthem of the Lawrence Textile strike and is sung throughout the world today.

As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women’s children and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread but give us roses!

Labor songs, protest songs, songs of activism and agitation have played a vital role in the history of the American worker and will continue to as long as there is disparity of any kind in our society today.

American Socialist: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs screens at the Digital Gym on May 11, 12, 13, 15, and 16 at 6pm except for 1pm for the Sunday matinee. The venue is located at 2921 El Cajon Blvd. For further information, go to: digitalgym.org/american-socialist/