Cover Story

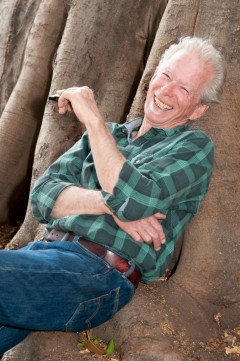

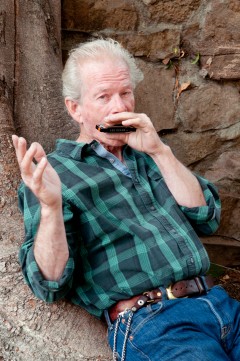

Robert Cowan: Harmonica Man Remembers

Robert Cowan. Photo by Steve Covault.

Cowan and Trombone Shorty

Cowan with the Strawberry Alarm Clock. Photo by Janet Anderson.

With the Neville Brothers in concert

Cowan with Joey Harris & Sara Petite at the Belly Up. Photo by Dennis Andersen.

Cowan with vocalist Whitney Shay

Photo by Steve Covault

POP

“Music has been an enormous part of my life, especially because of my father. I thank him because he brought the music to me,” says Robert Cowan, who will gladly recall “Pop’s” stories and his Bostonia Ballroom buddies from the old days: Ernest Tubb, Faron Young, and Hank Williams among them. Pop could sing like Tennessee Ernie Ford, but he had stage fright.

“These were folks who came out to barbeque with Pop before they had a show. When he was with them, they sang all of the time together, but when they tried to get him up on stage I watched him knock out four men one night trying to muscle him up there, pointing a finger at Faron Young and saying, ‘Never again.’”

Local harmonica veteran Robert Cowan says he is definitely his father’s son. “He was the kind of guy who loved people and, as a result, they opened their hearts to him.

“[Once] along the road, just outside Oceanside — what used to be the Johnson’s flower farm beyond Pendleton — there was a Buick that was pulled over,” Cowan remembers. “Two guys were standing outside of it, and they were Afrocentric. And Pop, being the man that he was, pulled over, because if you’re in trouble, you’re on the roadway.” They needed some help fixing a flat, and Pop was glad to help, changing the tire for them.

“When he finished, he wished them well, and they thanked him upside down, and as he was walking back, and the taller of the two men walked over to Pop and tried to give him a $50 bill. I watched my dad, through the back seat window, say, ‘No, thank you, Mr. Cole. Thank you for the beauty that you have brought me.’ It was Nat King Cole and his brother, who had played at the El Cortez hotel,” Cowan says. “‘This is my home telephone number. Would you do me and my family the honor of letting us take you and your family out to dinner should you ever be in Los Angeles?’ As a result of that, one day my dad did take him up on it and they became fast friends.”

An accomplished artist in other areas, who didn’t become a musician until halfway into life, Cowan has encountered numerous other iconic figures in his musical travels and formed memorable stories and friendships.

“I’ve had incredible good fortune. People have been very kind and very generous, regardless of how we met.”

THE ARTIST AND THE HARP

As a kid who could draw, he was the beneficiary of good training “when San Diego and its educational system valued the arts.” He recalls working as a student on productions in Balboa Park, including on sets for the Old Globe Theatre’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

“I knew right then that that was what I wanted to do.” It was a dream he was able to fulfill later as an award-winning production designer and director in films, television, commercials, and videos (including work on films by directors Ridley and Tony Scott). As an art director in the early days of MTV, Cowan networked with a lot of musicians, and more music industry connections grew from work as a stage designer on two world-wide tours with the Grateful Dead. He got to know Joe Perry while staging Aerosmith’s international “Pump” tour.

Another such contact led to the harmonica. He had known Little Feat guitarist Paul Barrere since before his playing days, when Barrere was a key grip. After front man Lowell George’s 1979 passing, the band’s future was up in the air and Barrere, back working as a grip, gave him a C harp. “’You’re one of the most musical people I know. You can play this,’ and I said, ‘No, man, I’ve tried.’ He said, ‘You’ve got the air for it. That’s a great thing.’”

Just a few weeks later, hired to design Rudy Records music studio in LA for Graham Nash, he was recruited by two engineers to play harmonica on a recording they were making.

“I go, ‘Guys, I’m not a musician.’ And they go, ‘No… come on’ and put me in the green room, put the earphones on me, and played the song — I had to have them tell me when to start and when to stop, because I wasn’t a musician and I wasn’t even really a player. When I finished, they said, ‘Come on in here, come on in here.’” On the way to the control room he met Stephen Stills, who he later had the chance to work and make some unrecorded music with.

The next day, they called in Norton Buffalo to play on the track, because they “needed a name,” despite Buffalo’s protests that Cowan’s version ‘had hit everything on this song.’”

A fan of Buffalo’s, he thanked him, and earned a compliment in return.

“’Well, kid, never stop playing because you really have a unique, beautiful thing that you do.’”

Cowan’s search for a harp mentor early on included John Mayall, who was rebuilding his Laurel Canyon house (with Cowan designing) after it burned in the 1979 Laurel Canyon fire. The British blues legend told him to get harps in all 12 keys, and practice to the car radio.

“Mayall said, ‘You’re playing with the very best musicians in the world. And, more important, the radio is terribly unforgiving. You can’t go back and make that mistake [again] until the song comes around again.’”

He took the advice, started carrying his harps everywhere he went and practiced in his car. The results in his playing showed up soon enough, a few months later at an LA harp contest.

“Lee Oskar, Larry Adler, Eddie Manson, and a number of all-time harmonica players were the judges of this thing; there were about a thousand contestants and it lasted all day long.

“It ended up that my friend and I got best duo — he played guitar and I played harmonica — but I got best harmonica of the day.” Afterward, he introduced himself to harmonica immortal Adler, beginning a friendship that would include playing duets together and a number of lessons. Cowan was beginning to make his mark as a musician.

HARMONICA MAN

Cowan was also developing a style, playing with artists in various genres, and getting exposed to the styles of many others.

“That’s basically where it all came from, and I have pursued it, because I have always wanted to do something musical and I can’t sing a lick,” Cowan says. “The harmonica became my voice, because it is a vocal instrument.

“In that same sense, I never wanted to be Little Walter, I never wanted to be Sonny Boy, I only wanted to be my voice. There’s only one of those cats ever, and their styles opened up worlds for all of us in lots of different genres. I have never really thought of myself so much as a bluesman, even though I have been offered and took that opportunity to go out and do shows with these amazing people, because there was so much more that I also wanted to play.”

Latin music and jazz are among his favorite genres, and he relishes opportunities to play in these styles. He also wonders why the Harp Fest focuses strictly on the blues.

“If you wanted to call it Blues Harp Fest, I could get that. There are cats here that can play Latin, which is one of my favorite things. To get into a horn section and be that guy in what would specifically be called ‘second line,’ like in New Orleans style, where they’ve laid this out, and you play with and around it.

“When I played with second line groups in New Orleans, that was a new thing to me, but being improvisational, what a kick in the pants!” Cowan recalls, “Playing with the more traditional guys, like the Preservation Hall Band, was a wonderful experience going and playing with them; it took me forever in this session to get what was going on, and I had Eubie Blake reach over and grab a harmonica and play the three little notes in this one piece that I was supposed to play, then hand it back to me. And I said, ‘But Mr Blake, why don’t you play it?’ And he goes, ‘Oh no. That’s a hard instrument. I play these.’” [laughs]

Cowan knows his comfort zone — abilities and limitations — as a player.

“When they call to ask me to play, I tell them: You do understand that I’m an improvisational player, what you see is what you get. Before we go into the studio, I let them know, ‘You can let me know when you want me to come in, or, if I may suggest, let me play what I feel and you can just take whatever you want. That’s going to be the easiest way.’”

Playing what he feels has paid off for Cowan, as he goes to jam with veteran studio players in LA.

“They’ve taken me in as a fellow brother in community, it’s kind of like After Midnight in a sense. And I’ve been so lucky to have them like what I do, and I keep going and I keep meeting all of these insanely good and generous players. But then again, it has been my experience, for the most part, that the more gifted the artist, the more generous they really are.”

Cowan has also played with a roots music Who’s Who, in locales that have included New York, Chicago, Austin, and New Orleans. On stage or in the studio, he has worked with Nash, the Neville Brothers, Little Feat, Bonnie Raitt, Taj Mahal, William Clarke, Albert Lee, and the Willie Dixon Band; he may soon be seen again with New Orleans funk band Galactic, as well as Trombone Shorty and his band Orleans Avenue. He also continues to play as a special guest of many local artists.

“There are regional styles and regional heroes. With New Orleans, there are so many styles — it probably has more styles than anywhere that are original. It’s like the differences in blues genres: Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, West Texas, Uptown New York,” Cowan says. “Adjusting your style, or rather adjusting yourself to their style, then playing in the voice that you have — to the tune. I’ve always believed that every song is a conversation. It’s all about listening and responding. What you do not say is as important as what you do say.”

In New Orleans, he became close to the Neville Brothers, playing with them and other Crescent City performers.

“The Nevilles are my extended family. Their children call me uncle, and the brothers call me brother; it is a great honor, for some 30 years now.”

One night Cyril Neville invited him to play at a gig where he was playing with trumpet legend James Andrews, Trombone Shorty’s older brother.

“We play a tune, we play a couple more tunes. You can see that James is looking at the bar. And he goes to me, ‘You want to take over?’ I say ‘Sure, I’ll play a couple of tunes, man.’ And he turns to the audience, then turns to Cyril and says, ‘What do we call him?’ and they both looked at each other and giggled and they in unison said, ‘Harmonica Man.’ ‘We want to introduce you to our friend, Harmonica Man. I know him as Uncle Robert, but we call him Harmonica Man.’ And as beautifully silly as that is, it’s something I treasure with all of my heart. Ever after, whenever I go into a club, everybody knows me as Harmonica Man.”

IN THE WORKS

Cowan keeps busy with his band, little monsters, as well as working with other local artists as a guest artist with a classic rock band and other projects.

“little monsters started out as a project because the people I was playing with, they’d come to town and ask if I had a band, because sometimes they were looking for people to open.” Cowan checked out bands for months and found that too many had two-set shows with a monotonous sound; “Sadly, a lot of it was a three-hour song.”

He started looking for special musicians and gradually found them: guitarist/singers Phil Diiorio and John January, female singers Annette “da Bomb” Magee and Keke Buché, sax man Chuck “the killa” Arcilla, bassist Jodie Hill, and drummer Ric Lee.

“That was the first little monsters band, and it’s taken a couple of machinations since then, but the general theme and the principle of it is that we’re going to take songs and make them our own. We can take a song and almost make it an original, by taking it places that other people haven’t.” The latest version of the band includes Arcilla, January, and singer Ayanna Hobson, Frankie Dee on keyboards and vocals, Dale Davis on bass, and drummer Jack Nathan.

“The reason I put so many players together was that I wanted to do everything from field holla a cappella to big band swing, so everybody had to contribute in singing — and monsterize it.”

“You can sit back safely and go, ‘I’ll do this.’ Why? What are you doing it for if you’re not going to discover new ground?”

Cowan is also working with Verdell Smith, a local writer/singer/guitar player.

“He has a group called Soul Ablaze, and he’s a very talented man. He’s written some reggae-meets-rhythm-and-blues, really spectacular. And I’m behind a girl named Jonnae Thompson, and I’m part of her little background band, called the Playground. She does Erykah Badu, Jill Scott kind of jazz, rhythm and blues; I guess you’d call it soul jazz.”

Other projects on the horizon include a project with former Oingo Boingo/Strawberry Alarm Clock member Steve Bartek as well as a continuing role with the Clock. The excellent musicians in the current band can sound like the New Orleans funk legends The Meters, as well as playing their psychedelic pop singles.

“I’m already on the new Strawberry Alarm Clock album, and I’ve been playing with them as a guest artist for a couple of years now.”

Cowan has his own CDs planned as well.

“I don’t have a name, but the first one I’m doing is more of an Americana/alternative; I’m including songs by local artists as well as some by people that I’ve known or played with, or famous tunes, as covers. It will range from almost folky to country rock; I’ve got the tunes picked out. It’s probably going to be a double CD, because there’s just too much that I want to lay down and, in a sense, I’m inviting artists as my way of thanking them. It’s all covers, some of it originals by the artists who will be playing.”

Steph Johnson and Preston Smith will be featured on “You Don’t Know Me,” made famous by Ray Charles, and musicians from little monsters will appear on the solo projects.

“The second CD is blues and jazz, every kind that I can think of. Everything from Blue Green by Miles Davis to things by Elmore James and my late, great friend Willie Dixon.

I record live. Everything by little monsters is live and we did it in seven hours, the first Monsters album. I get everybody in the studio, we divide everything up so that the engineer can have some control over it. But I believe that whatever you’re going to do needs to be in the moment.”

BRUSHES WITH GREATNESS

Recounting his most memorable or craziest gigging or recording experiences, Cowan is liable to drop some jaws.

Take, for example, when he was working on a play’s stage design in LA and Bill (Count) Basie was among some of the musicians brought in by the play’s music directors (Putter Smith and Red Callender) to contribute some music. After a series of circumstances, he was standing in at the end of the horn circle with his harp.

“They had this guy that they wheeled in sitting… in a wheelchair, at the piano. Little tiny guy, with a hat, and this tall, elegant, beautifully dressed man next to him, just standing. And the guy was amazing. After they played the tune, I went over to talk to the director, and on my way out I passed by the piano and people are talking about stuff. So I played my little bit, and as I’m on my way out, I felt this hand on my shirt, ‘Hey, where you think you’re goin’?’ [gruff voice] ‘Well, I have to go back to the stage; I’m designing the sets for the play.’ ‘No, you ain’t goin’ nowhere, I wanna hear some more of this.’ And I said, ‘But sir, I don’t read, I’m not a musician.’ And the tall, elegant man behind him said, ‘Neither does Mr Basie, he has other people to do that for him.’” Cowan was later invited to play on two as yet unreleased pieces for Basie’s last album project.

Cowan recalls another chance encounter on a trip with his wife, to Telluride, Colorado.

“It’s how I met Buddy Guy. He was playing at this one-gargoyle bar. Heard the music, went by, saw the band; there weren’t a lot of people in the bar, they were just having fun, Cowan says. “So, first set’s over and I walk up and I go, ‘Buddy, I know so and so, I know you know them. I’ll buy you all a drink if you let me play one tune.’ And he goes, ‘Well, what do you play?’ And I opened up my kit and I could see his bass player go, ‘Oh, my God, another harmonica player. Like, please somebody shoot him… security!’ [laughs] And he said, ‘Well, we get our drinks here for that, but a couple of songs in, we’ll have you come up and play a tune.’” The one tune turned into playing the rest of the night.

After Cowan went fishing the next morning, Guy and pals showed up at his room, ate fresh-caught trout for breakfast, and invited him to sit in that night as well. He still plays with Guy occasionally.

HERE IN RIVER CITY

Cowan has a lot of admiration for lesser known but very talented local musicians including harp players.

“Troy Sandow is not only an exceptional bass player, but he says more with less than I think I have ever heard in any harmonica player alive.” says Cowan, who also especially admires “Billy Watson, Lance Dieckmann, Jon Atkinson and Harmonica John” — among local harp men.

Jeffrey Joe is a particular favorite, as a balladeer, harp player, and wit.

“I love Jeffrey Joe, he is incredibly melodic; he’s not only a great balladeer, a wonderful songwriter, and a divine man, but I could listen to the cat play harmonica forever.”

Among non harp players, he admires “Sara Petite, Nena Anderson, and Adrian Demain, anything that those guys are involved in or doing. I also had the privilege playing with the Bastard Sons of Johnny Cash — Mark Stuart has promised me that he will do a tune on my Americana album; he’s the vocalist and the songwriter in that band. Adrian is Nena’s guitar player and is famous in his own right.”

“Thank you, God, that Steph Johnson is getting air time, because you can go to other cities and you can say Steph Johnson and they go, ‘Oh my God, isn’t she wonderful.’ And she’s only going to get better.” Other favorites include jazz players Rob Thorsen and Ed Kornhauser, and Americana artist Ken Lehnig, on whose CD he recently played. Cowan is also a big fan of the Farmers (and Beat Farmers before them), and considers Farmer axeman Jerry Raney “the most relentless” guitarist he has ever heard.

“I think that San Diego has, per capita, more musically gifted people than anywhere else I have ever been. I am so grateful to be here to share in the beauty they bring.”

DIVINE CRAZINESS

“I have had a hundred crazy gigs, but this one was not planned.”

In about 1992, the stars aligned and even Cowan was rendered nearly speechless. He went to an album debut in Hollywood for Jean (Toots) Thielemans’ The Brasil Project.

Thielemans, a friend of Antonio Carlos Jobim, had rounded up some top Brazilian artists for the album, including Ivan Linz, and they were playing some of the tracks.

“They have a break and they’re introducing everybody, and everybody is mingling. I went with a friend of mine who was a writer for the now-defunct Hits magazine. As my friend Joe was talking to and interviewing him [Jean] he goes, ‘Oh, my friend Robert here, he’s a harmonica player and he just loves that Brazilian stuff. You should hear his Brazilian stuff.’ And I’m ready to KILL Joe. [laugh]

“And Jean never missed a beat. He looks at me and goes, ‘Well, if you’re a harmonica player, you have a harmonica on you. Would you care to join us?’ and I’m going, ‘Are you sure?’ ‘Oh, we’d love to have someone come and help us here, I get to play guitar.’ And so they did one of Jobim’s tunes. Now, as I’m getting this invite, I look over in the corner and there’s a small man, immaculately dressed in white. I go, Oh my God. Mayall was there, Leo Kottke was there, Lyle Lovett was there, and this little tiny man dressed in white, and I go, ‘Oh, my God, it’s God,’ and my friends Joe, Jean, and Ivan look over and they start to giggle. Joe goes, ‘What?’ and I go ‘Jobim.’ And he turns around and says, ‘Yes, I am Jobim.’”

After the once-in-a-lifetime set, Jobim invited him to accompany the band to play some more music that evening. Cowan called his wife (an ardent Jobim admirer) to let her know about his chance to play with the Brazilian immortal. She didn’t believe him-her response to his news was, “You are not!”

“He snatches the phone out of my hand and he goes, ‘Yes, I am Jobim. May your husband come and play with us? We just love the way he played, we just played a few tunes. Ah, thank you so much. Your wife wants to talk to you.’

“Well, I get in the limo and I don’t know where the hell we’re going; we’re talking about Brazilian music, which I love, anything Latin. The next thing I know, we’re pulling into the Hollywood Bowl — that was where they were going to go play music. And Jean was a guest, and Ivan was a guest, because it was Jobim’s night. It would be his last performance at the Hollywood Bowl, and Tom [Jobim] was my friend until he passed.”

If Cowan’s musical career can be summarized by one guiding principle, perhaps it is this:

“I know what I am as a harmonica player and I’ve had wonderful good fortune, but I also believe, as my brothers the Nevilles said. The first time I played with them, I looked at Art and I looked at Charles, and said, ‘Is that okay?’ And they went, ‘You’ve got something to say, little brother, keep saying it.’ So I will. If you can’t listen to those cats and glean something from it, then you ain’t listening.”