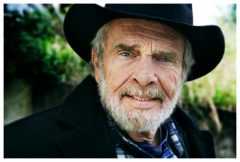

Yesterday And Today

Merle Haggard: A life well-lived

How do we say goodbye to our legends in American music? It’s a hard thing that fate asks for us to do. Especially when it’s an artist who has changed the musical landscape over the course of a six-decade career? For California country singer-songwriter, Merle Haggard, who died on April 6, on his 79th birthday, the goodbye was much like his songs: simple, direct, unadorned, and honest.

According to a report by L.A. Times, the funeral was held at Haggard’s ranch in Shasta County; his beloved bus, the Silver Chief, served to shield the western wind that blew through the intimate ceremony. His home ranch was unusually quiet and somber with the crystal-like mountain peaks of Mt. Shasta hovering over the horizon.

But, like his song “Running Kind,” the day must have felt like a gentle reminder of the man himself who all of his life had trouble staying in one place too long.

Country singer and friend Marty Stuart officiated the service. His band, the original surviving Strangers, were there. Appropriately, Lefty Frizzell’s “I Love You a Thousand Ways” played on the P.A. It was Lefty who Haggard worshiped when he was a 14-year-old juvenile delinquent in and out of trouble. Frizzell was the country singer, whose career peaked in the 1950s, who inspired Haggard’s songwriting and vocal style the most.

Marty Stuart, his wife, country legend Connie Smith, and former Stranger Ronnie Reno sang “Life’s Railway,” “Precious Memories,” and his classic song of the road, “Silver Wings.”

But it was when his old friend, Kris Kristofferson took the stage that the poignancy of Merle Haggard’s passing took root.

In the late 1960s Kristofferson was the polar opposite of Merle Haggard, who had scored a huge hit in his song “Okie From Muskogee.” The song was embraced by the country’s political right in a backlash against student protests over the Vietnam War and all of the trappings of the day’s youth-oriented counter culture. In 1969, Kris wrote a song in response, “The Law Is for Protection of the People,” in which he would ad lib the words: “We don’t need no hairy headed hippies scarin’ decent folks like me and Merle.” They were the hippie and the redneck.

In the years since the two artists grew to be close friends, frequently touring together. One of Haggard’s last concerts was in January, with Kristofferson, in Beverly Hills. As they played that night, Haggard was in the last days of his life and Kristofferson was suffering from years of struggle with severe memory loss.

At the funeral, Kris sang his own words:

Was it wonderful for you?

Was it holy as it was for me?

Did you feel the hand of destiny?

That was guiding us together?

I’m so glad I got to dance with you

For a moment of forever

He then, launched into Haggard’s “Sing Me Back Home,” with the wind blowing through as the lyric sheet blew away from his view.

Marty Stuart joked that it was Merle wanting to break up the somber occasion.

A group sing of “Today I Started Loving You Again” ended the funeral on just the right note on that breezy day near Haggard’s beloved Lake Shasta.

As Merle Haggard was carried to the ages, it is not an understatement to say that we won’t see the likes of him again. We will not. He’s the last of a breed of singers that began with Hank Williams. If, as Kristofferson once said, Johnny Cash was the father of our country, then Merle Haggard was certainly one of its founding fathers.

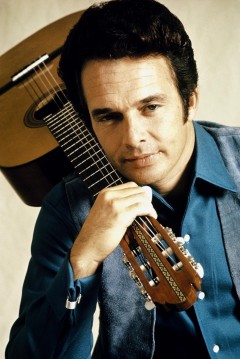

Musically, Merle Haggard was a jack of all trades and a master of them all as well. From lead guitar player to singer, songwriter, fiddle player, poet, and country western innovator, he grew to be one of its brightest stars; it seemed he did it all.

Why did his songs have such depth–even in the country singers of his day–which seems so lacking today. Like Hank , Haggard lived what he wrote and sang. He was there first hand for it all.

He was a vocal stylist that transcended the country genre, he was poet and a lyricist whose only peers would be on the top rung of America’s best country songwriters: Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams, and Willie Nelson. He loved them all. But, he had his writing and singing trademark.

He championed the Bakersfield sound in style, which broke the Nashville sound tradition ten years earlier when Willie and Waylon and the Outlaw Movement showed up. He fearlessly brought in an unlikely fusion of old timey-style jazz and country based on his love for Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. However, he took things further by adding a brass section to the Strangers. They could as easily lapse into New Orleans style jazz as they could play Texas Swing to perfection.

His legacy of 41 number one songs showed how skillfully and seamlessly interwoven an ordinary-sounding song hook can be. He made them real because they were deeply personal yet universal enough to invite us in to enjoy his moments of song. It was as though he was talking only to the listener, telling stories and delivering hard-fought life lessons. With hits like “Today I Started Loving You Again” and “Tonight the Bottle Let Me Down,” he took songs that could have easily been country parodies or rendered as clichés and turned them into an authentic baring of the soul captured in a three-minute song.

Like his Bakersfield compadre, Buck Owens, he was pure California country. If Owens brought in the fusion of country music with blues, rock, and Mexican ranchero music, Haggard gave the sound its content and context through songs that told the stories of his youth exactly as he lived them.

To understand his style and body of work, it’s important to look at the ingredients of his life.

His stories are many–and most of them fairly hair-raising–showing an attitude of risk that on several occasions could have lost him his life. It was an attitude that also brought him artistic success in his music career: the risk taker unafraid to try something new.

Haggard’s travels were broad, wide, and deep into the American psyche. From diary-like songs of his childhood to heart breaking love songs, he journeyed from the Dust Bowl to the Hollywood Bowl with a life-changing stop-over in San Quentin.

By the time he was 20, he had already lived several lifetimes. It is well-told in his entertaining and 1999 conversational autobiography, My House of Memories, which was co-written with Tom Carter.

Haggard’s story reads like a combination of Cool Hand Luke and Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory. He was declared incorrigible during his adolescence and young adult years. At times it seemed that no prison, jail or juvenile lock-up could keep him bound. His escapes were many. He frequently hopped freight trains just for the romance of it. As a juvenile delinquent, he moved fast and hard and a left a trail of bewildered police, prison officials, and all manner of criminals and convicts black and blue from chases and roadside fist-fights.

Haggard was born in Oildale, California, just outside of Bakersfield, in 1937. It was the middle of the Dust Bowl migration when families moved en masse to California to escape the drought and deadly dust. His family came the year before his birth. The references to his early life are scattered through his songs. “Tulare Dust” says it most clearly.

I can see mom and dad with shoulders low

Both of ’em pickin’ on a double row

They do it for a livin’ because they must

That’s life like it is in the Tulare dust.

He was incarcerated 17 times as a teen and young adult.

Music is what saved Merle Haggard from a life of crime and incarceration. His mother gave him his first guitar. His older brother showed him his first chords. His great uncle and family friends taught him more. His enthusiasm for country music was as unstoppable as his magnetic draw toward a criminal life.

It was the song that drew him in. The call of the story through music haunted him.

He seemed tuned into that secret radio station most great songwriters have drawn from that only they can hear. During mandatory classes in the institutions, where he spent much of his teen years, the teachers commented that he seemed to be in a dream world. He would respond that he was making up songs in his head.

His creativity and love for music became Haggard’s redemption. While many country singer-songwriters sang songs about prison and mama; it was a true story when Haggard sang “Mama Tried.” He really did turn 21 in prison.

There were a few events that would help turn Haggard’s life around. In 1953, when he was 16, between incarcerations, he was at a Lefty Frizzell show in Bakersfield and was allowed backstage with a few friends before the show. He sang two songs for Frizzell. The country legend was so impressed he refused to go on stage unless young Haggard was allowed to first sing a few songs. Frizzell then handed young Haggard his guitar. It was the first time Merle Haggard held a professional’s guitar. It had Lefty’s name engraved on it. As Frizzell handed him his guitar without knowing it, he was passing the country music torch to a new generation and to one of its most important future artists.

Many years later, Haggard would buy the same guitar.

Ironically, this happened during the peak of Lefty Frizzell’s career. In the 1960s, as Merle Haggard’s musical fortunes were rising, Frizzell health declined and he died as a result of alcoholism in 1975.

It would be years before another encounter would offer Haggard a new outlook on life.

In 1960, when Haggard was 27 years old and in San Quentin, Johnny Cash performed. It was the first time Haggard saw just how powerful the music was as he watched the eyes of the convicts respond to the show. In interviews over the years, Haggard pointed to Cash’s appearance at San Quentin as being a turning point for him. Something slowly began to change in him and he began turning away from the path of a career criminal and toward a life in music.

Many years later, in the 1980s, Haggard would return the favor. When Cash was recovering from a life-threatening illness, Haggard decided to go off his beaten tour path. He directed his Silver Eagle bus to the Tennessee hospital where Cash was slowly coming out of a near-coma state. Barely conscious, he said that he felt a presence in the room, which was something he couldn’t explain, but he there was a strange sense of comfort there. Then, it was gone. It only lasted a few minutes, as Cash recalled, later saying, “I knew it was Hag.”

Rick Rubin told a bit more of the story in his American Recordings liner notes. Before leaving the room, Haggard leaned over and put his forehead on Cash’s forehead. He then quietly whispered, “Ah, John, it’s gonna be alright.”

Such was the connection between these two country artists.

After his final stay in San Quentin, Haggard entered the 1960s a new man who was compelled to make better choices. The music absorbed him. He was in demand as a lead guitar player around the Bakersfield area and cut demos of his original songs. Some thought he sounded too much like Lefty Frizzell. But, as he continued, he would begin scoring national country hits in 1964, the same year that Frizzell scored his last hit song, “Saginaw, Michigan.”

Between 1965 and 1989, Haggard would record 41 Billboard #1 songs. He also scored 63 songs in the top three.

His career has been unique. He is in the small company of country singers who remained significant through every era of their career. And even with his criminal life behind him, he still managed to foreshadow the outlaw legacy as he defied the rules for traditional country singers and songwriters.

Through his years of success he eschewed any person or group who tried to box him into any political or religious perspective. He was fiercely independent and it showed in his songwriting. While songs like “Okie from Muskogee” and “Fighting Side of Me” spoke to a conservative perspective, his latter day songs like “America First” and “That’s the News” reflect a more libertarian outlook on war and the events of the day.

But these were only one side of his legacy. He took the honkytonk drinking song, so championed by past country singers, and added a twist of irony. This can been heard on the hit song “Tonight the Bottle Let Me Down.”

His drinking songs were many, as were his cheating songs. But, even here he added a new depth to the subject matter on songs like “Go Where the Lonely Go.”

The songs that most reflected his legacy are those that reference the labor camps of the 1940s and his childhood. “Daddy Frank,” “Hungry Eyes,” and “They’re Tearing the Labor Camps Down” capture the Oklahoma migrant experience as well as Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads, only from the point of view of someone who grew up after the migration.

His love songs were poetic and haunting. One of his best, “My Favorite Memory,” is a stirring love song recalling past memories and what’s been lost in a relationship.

His crime songs exceeded those of Johnny Cash in authenticity. “Mama Tried,” “Lonesome Fugitive,” and “Sing Me Back Home” carry a depth of lyric and emotion in an intimate way as they tell the true stories of Haggard’s youth.

There were songs written stylistically for a western swing sound, like ”Cherokee Maiden” and “Rainbow Stew.” Then there were the songs about moving. “Silver Wings,” “Big City” and “The Restless Kind,” to name a few, illustrated the experience of his life on the road.

He wrote from so many different perspectives, it’s as though he really did live several life times.

Even well after his years of number one hits were long past, Haggard experienced a career resurgence helped along by the Americana music movement. It began in 1996 when Iris Dement, Dave Alvin, John Doe, and many others released the tribute album Tulare Dust, one of the unifying and pivotal albums of that movement, which all hinged on love for Merle Haggard.

Over the years he became the elder statesmen of new artists and fans. His legion of growing young fans include artists like Jason Isbell, Chris Stapleton, and Sturgill Simpson.

In the first decade of the new millennium, he released a string of albums that drove home his veteran, grandfather status in the young Americana movement. Even more than his earlier albums, they were focused singer-songwriter affairs with his same flair for making autobiographical subjects revealing and universal. If I Could Only Fly, Roots Volume 1, Haggard Like I’ve Never Been Before, I Am What I Am, and Working in Tennessee showed a veteran artist who simply continued with business as usual, writing and recording brilliant, authentic country songs. Last year, his third duo outing with Willie Nelson, Django, and Jimmie, premiered at #1 on the country Billboard charts.

During his final years, he rarely stopped touring. His family stood by him. Theresa, his wife of 23 years, brought him a new-found peace with the two children they raised together. He was married five times, but it was Theresa who helped him find the family life he missed as a young man and as a country star.

Through a rocky road from labor camps to honky tonks and prisons to country stardom, Merle Haggard never lost sight of his own musical integrity as an entertainer and an artist. He was one of a handful of singer-songwriters in any genre who we can call a national treasure. He is also one who we can easily call a poet and a storyteller.

As the news hit social media on April 6, I felt like I was losing a close personal friend whose music helped me through hard times and good ones as well.

In the end, there really is no way to measure how important an artist like Merle Haggard was to our culture. Time will tell that. His life is a living testament to the power of music, the redeeming value found in the song, and the love that awaits with a bit of faith and the desire to remain true to oneself.