Cover Story

Treading the Boards with Mike Keneally: Maestro masterstroke in 9/8 time

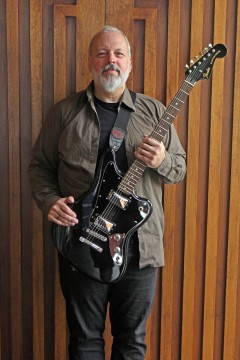

Mike Keneally. Photo by Dan Chusid.

Mike at the piano. Photo by Dan Chusid.

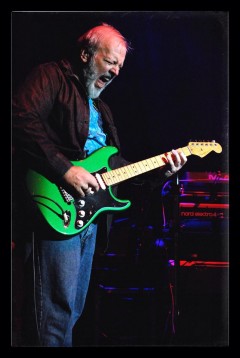

Keneally in action!

Photo by Dan Chusid.

In the liner notes to the 1968 Mothers of Invention album, We’re Only in It for the Money, Frank Zappa instructs all and sundry that, before checking out the ultimate track on the LP, “The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny,” go and “dig up” a copy of Franz Kafka’s short story “In the Penal Colony” and read it before coming back to drop the needle. It’s a classic case of the artist suggesting the proper context to more fully appreciate and experience The Work. Awareness = potential profundity.

It’s a process familiar to any student of art history. Dali’s iconic 1931 painting, The Persistence of Memory, is a powerful image in its own right; to explore the circumstances of how it came to be is to multiply its potential impact upon the psyche, and/or the soul, tenfold. Aided and abetted by an enlarged sense of perspective, in Life, as in Art, understanding frequently ends up as the booby prize, i.e., experiential wisdom masquerading through the maxim that all knowledge is indeed power.

That’s why all art is potentially dangerous and subversive by its unerring ability to undermine conventional attitudes, particularly if those conventions support and encourage the illusion of limitation. Because, in its purest expression, music demonstrates that the only true limit to human endeavor is dictated by the imagination, in tandem with awareness.

Music may, in fact, be the highest form of communication that we currently possess as a race, transcending, as it does, logic and rationale. So — beware of new ideas, for they contain the ability to radically alter your perception of Self, and the cosmology of where you perceive yourself to be, in the universe. Forewarned is forearmed.

In our current pop culture epoch, the necessity for prerequisite contextualizing has never been more vital (in other words studying the narrative strands of history). What you see and hear in the medium of radio and television is truly what you get: a consistent stream of pablum. There is a dire need for alternative sources of information and education — with music appreciation classes almost unheard of in today’s curriculum, it’s a nearly “subversive” act to become educated beyond the bounds of what is authorized in the state and church-sponsored programs of our current “information age.” It’s insanely considered by some to be an act of high patriotism to take George Orwell’s 1984 or the Bible at face value and not read either work between the lines for its poetry or parable.

Well, broadening the context of how to hear organized sounds and silences, simply because new paradigms are being proffered, is just one of the many reasons to rejoice around the oeuvre of San Diegan Mike Keneally — this musical maestro is dangerous in the way that all art is potentially dangerous. The unbridled joy and virtuosic passion, expressed throughout his entire body of work, is a stellar testimony of what can happen when a gifted soul is given a nurturing environment in which to perpetually blossom. Keneally is that rarest of birds: a guy who was encouraged and supported by his family and taught to follow his bliss, remaining courageous enough to trust that the Universe will provide and support his endeavors. Keneally’s history is downright inspirational, and it is the glorious subtext to understanding the profound swath that his mind-blowing discography of 25-plus titles has blazed over the past three decades.

The world at large first heard about him after he snagged a coveted spot as the “stunt guitarist” and keyboardist in Frank Zappa’s last touring group of 1988 (well represented across six Zappa titles). When that stage unit famously imploded in mid-tour, Keneally returned to San Diego and soldiered on with the quartet, Drop Control, featuring his brother Marty on guitar, bassist Doug Booth, and drummer Alan Silverstein. Drop Control was a logical extension of The Tar Tapes, home recordings that Mike and Marty crafted together and released on a series of five cassettes in the ’80s and ’90s. Keneally’s solo debut proper was released on CD in 1992: hat. Since then he has averaged roughly one album per year over the past 23 years. His discography is immense, sprawling, eclectic. The level of quality throughout is staggering and will likely leave you gobsmacked. Highlights along the way have included a trio of live albums (Half Alive in Hollywood, Guitar Therapy Live, and bakin’ @ the potato!); a collaboration with the Netherlands’ Metropole Orchestra (The Universe Will Provide); a piano deconstruction/reinterpretation of the songs of Steve Vai (Vai: Piano Reductions, Vol. 1); two Odds & Sods-style collections of castoffs (Wine and Pickles and You Must Be This Tall); and a high-profile, songwriting collaboration with Andy Partridge of XTC on 2012’s triumphant Wing Beat Fantastic. His current work-in-progress is Scambot, a conceptual trilogy, which he is smack dab in the middle of crafting.

Keneally just came off the road in mid-November after spending the previous 18 months performing 143 concerts around the globe, on the Unstoppable Momentum tour with Joe Satriani, bassist Bryan Beller, and drummer Marco Minnemann. Before the tour with Satriani came to a close, he also played, in October, at the Festival Supreme in Los Angeles with the ongoing fictional cartoon conceit of Dethklok. The “torture” never stops for Mike Keneally.

While it’s true that Keneally may be far from a household name, little or no introduction should be necessary for this incomparable veteran of ensembles that have featured the likes of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Robert Fripp, Steve Vai, Henry Kaiser, and Prairie Prince, to name several upper-echelon music icons that Keneally has traded licks with. Perhaps we should hit the refrain and take it back to the top.

*********************************

Michael Joseph Keneally was born December 20, 1961 in Long Island, New York, the youngest of five siblings, with two sisters and two brothers. Raised initially in the hamlet of Plainview, his family moved to San Diego in the middle of 1970 when he was eight years old. “I got an electric organ for my seventh birthday and I just messed around initially,” he says. “I didn’t have any lessons while I was in New York, but when we moved to San Diego we went to the Balboa Music Center, and that didn’t work out for some reason. We eventually found our way over to the Sears music department. I remember standing in the record department looking at Bloodrock 2, waiting for my organ teacher to come out of this suite of offices in the back. It’s so weird how you remember [things like] that. But eventually I found this organ teacher, Fran Morris, a private teacher who was just incredible, and I worked with her for about four years.

“She taught me a lot of basics of music. She used the Great American Songbook as her curriculum, so I was learning ‘Begin the Beguine’ and ‘Spanish Eyes,’ all this stuff with very rich voicings. So I had all these clustery, strange things in my awareness from pretty early on.

“Learning how to manage that stuff with my hands, I was able to gradually decode more of what I was hearing on the records that I was listening to, which was Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and Yes, and Todd Rundgren — all this stuff that’s like a dense, harmonic thicket. I managed pretty quickly to be able to decipher all the stuff that was on the records. My ears became more of a tool than my eyes when it came to learning music and it became much quicker for me to learn a song off of a record than it would ever be to read it off a chart. When I had my audition with Frank [Zappa] it was solely because of my ear that I was able to get that gig. He specifically put charts in front of me — in one case I struggled to read the first bar and he just took the chart away. In the second case he put down a chart for a song that I knew already and I faked it from having heard it a thousand times, and Frank wasn’t a sight-reader either, so he didn’t know if I was reading the chart or just playing it by ear for the first few bars. He goes, ‘Wait, wait a second.’ [laughs] ‘Are you reading that chart or are you playing it by ear?’ I said, ‘I’m playing it by ear.’ And he got a kick out of that, the fact that I had such passion for his music that it wasn’t a problem for me to call the stuff up, but when he put a chart in front of me, that was a problem. If it was a really tough song I needed two days on my own with the chart before I was ready to play it for anybody. As compared to other people in the world who are sight-reading monsters when you put anything in front of them…

“If it’s a chord progression, I can read a chord progression. But even then, if it gets into a lot of jazz voicings where you’re talking a minimum of six characters in the chord name, that stuff doesn’t just leap readily to my brain. I’m not trained as a jazz player, so a basic part of the jazz vocabulary is not a basic part of my vocabulary, even though I listen to a lot of it and it has certainly had an influence on what I do. And there have been times over the last two decades where I thought I would really love to take some time away from the standard path that I’ve been on and study with a jazz player and just do that exclusively for a few months and see what happens on the other end of that. But the time never presents itself.

“I’m always trying to play something that I’ve never played or heard before. That remains my top priority. That gets more and more difficult the more you continue working with the same vocabulary, harmonically. I find that there are still a lot of areas rhythmically for me to pursue, and that’s where I find myself spending most of my time when I’m improvising or just trying to create something new, bringing more the feel of ‘ah, this is a place I haven’t been before,’ and, ideally, a place that I haven’t even really heard before, because that’s really what I think we’re all after, to some degree. Even though, obviously, the notes are available to me, I find that there are ways in which really, really superb jazz musicians conceive of melodicism that is just so inspiring. That’s what feels like to me where the next horizon resides. It’s so deep. You listen to Wayne Shorter play, or Herbie Hancock, and for some reason vistas are opened in a way that no other music I hear quite does. It’s a place I’d like to spend more time in.”

When you say “a rich voicing,” how would you describe that?

“Well, let’s say that if you’re in the key of C, you could choose to play a C triad, which would be C, E, and G. Or you might choose to play a C minor triad, which is C, E flat, and G. The songs that I would often find myself playing were more clustered. If it’s in the key of C, perhaps I would be playing a G, which is a fifth in the key of C; an A, which is a sixth in the key of C; C itself — the root; D which is the second or ninth degree; and E, which is a major third. So a five-note chord consisting of the fifth, sixth, first, second, and third: very clustery. And if you play that over a C bass then you get a very rich, major chord feel. If you play that over an A bass, all of a sudden it’s a very clustery, haunting A minor feel. So even just changing the bass note, if you play those five notes over a F then it’s a very rich F major 9 and you’re getting into Laura Nyro and Todd Rundgren territory where you would have somewhat more unconventional harmonic choices over a bass note. Brian Wilson, as well, if you listen to the bass lines on Pet Sounds, it hardly ever lands on the root, and it’s one of the things that gives that album its misty, somewhat ethereal and distinct feel. It’s not ‘four-square’ music. There’s a lot of ambiguity in there, and that’s why it keeps people listening. That’s one of the things that has fascinated me in music, the application of chord voicings and what’s happening in the bass underneath that. There are just infinite universes to be explored there and where I find that I am reaching for something more at the moment is melodically. I feel pretty complete in the harmonic and the bass realms. And then as far as melodies on top of that — I mean, I’ve done well — I think I can do way, way better. That’s where I see myself focused most extensively in the time to come.”

************************************

You’re currently working on Scambot 2, that’s like your 19th record as a solo artist, isn’t it?

“Or 25th if you count the special editions of albums that contain a second album. I really like those second albums. Like Parallel Universe, which came with The Universe Will Provide. And Wooden Smoke Asleep and Songs and Stories Inspired by Scambot 1. Those are all three really odd, interesting albums I think. And I do think of them as separate entities, even though they didn’t get a ‘first-echelon’ release.

“But right now, I’m working [exclusively on] Scambot 2. This is the first time in a while where I’ve had only one focus, as far as my solo albums go. The period from Wine and Pickles to You Must Be This Tall, all of that stuff bled into each other and sort of comes from one place, one era.”

Were you creating consistently, and then deciding after the fact, which canvases to put the pieces on?

“Essentially, yeah. There were many songs that I created during that time that I wasn’t absolutely certain where they were going to end up. It started with Scambot 1 as the primary project. And then while I was working on Scambot 1, I began working on Evidence of Humanity, which is a collaboration with Marco Minnemann. And it was clear that the Evidence of Humanity music, because it came from this Minnemann-derived concept, was destined for that album. But as I was working on Scambot 1, I was also heading over to Andy Partridge’s place [in Swindon, England] and writing songs with him. And at that point I didn’t have an overarching vision for where things were going to end up that we were doing; it was just ‘yeah, I’m writing with Andy.’ Because when you have the opportunity to write with Andy, you do it. I wasn’t concerned about what the album cover was yet, you know? And I didn’t know if these songs were going to be part of Scambot. I didn’t know if they were going to be a Mike Keneally album. I didn’t know if Andy was going to be involved in the performing of the thing. At that point it was: we’re just going to write. And then I found, I was working on Scambot 1 and I was going on the road with Joe Satriani a lot and I was going on the road with Dethklok a lot. And… years went by. I had done two writing sessions with Andy: one in 2006, one in 2008. As of 2010 I thought I was going to go over there one more time and have one more session. And then I read an interview online with Andy where he’s saying, ‘I don’t know what the hell Keneally is doing. I keep expecting him to record these things.’ And I’m like ‘really?’ [laughs] I didn’t know.

“So I said, ‘Okay, that’s all the prodding I need from the universe to get this thing done.’ Let’s start recording these songs and see what they are. So, without being particularly concerned about what the final form was going to be, I just started making recordings of the stuff that I had written with Andy up to that point, some of which was in very complete condition, some of which was just the barest snippets of a concept of a song. In particular, the song called ‘Miracle Woman and Man’ was maybe 30 seconds of a musical doodle, which I ended up taking in a completely different direction. But a song like ‘I’m Raining Here, Inside’ or ‘Wing Beat Fantastic’ were essentially completed lock, stock, and barrel in terms of music and lyrics by the time I stopped writing with Andy.”

Would you call those nose-to-nose collaborations?

“Yeah, ‘Wing Beat Fantastic’ certainly was, where every chord and every lyric was written with both of us facing each other and going, ‘Okay, what comes next?’ ‘I’m Raining Here, Inside’ was a different story in that it was a series of lyrics Andy already had in a lyric book, complete. There was no music for it. Andy said he couldn’t figure out at all what sort of musical setting it should have.

“And I went, ‘Okay.’ I put it up in front of me and I just looked at the words and I swear to you in five minutes that record just sang out. I was on piano at that point. And what’s on the record is just what felt to me the only possible thing you could play along with those lyrics. That’s where collaboration is a cool thing. And then there were other things like ‘Bobo’ where we worked on the music together and then I ended up doing the lyrics entirely on my own after I got back to California. Or ‘You Kill Me’ was something where we had the basics of the verses and a chorus idea and Andy had written probably 95% of the lyrics on that one. And then when I got back to California I realized I liked the basic feel of the song but I thought it needed more sections; it needed to get a little more epic. Andy described it as starting out as this campfire acoustic thing and I ended up turning it into a Who record from the Who’s Next era or something. It’s electric and kind of big and anthemic in a way. And I wrote some new musical sections that didn’t have any lyrics yet, I sent those sections to Andy and he emailed me new lyrics to the new music parts that I had written. So in some ways the collaboration continued even after we were thousands of miles apart. And all the songs as I was working on them, I was sending Andy preliminary mixes of the songs in progress. And he was writing back with very specific things: ‘You should try to sing this this way.’ ‘I don’t know about the instrumentation in this part.’ He sort of associate produced from a very remote location.”

Wing Beat Fantastic is such a beautiful record and it really is singular in the sense that it sounds very much like you, but there’s that third thing of collaboration that makes it very unique to your catalog.

“It definitely stands apart. Believe me, I’m aware of it, and as I’m writing songs for Scambot 2 right now [the idea] is always lingering in the background that there’s a real standard there to kind of be inspired by, thanks to writing with Andy. Now that I’m writing on my own again I want to make sure that the stuff doesn’t suffer by comparison. Again, you don’t want to be guided by that kind of competitive thinking when you’re doing a song, but every time I make a record I want it to represent, at least to me personally, some advance in a direction that I haven’t gone before. And I’ve done a lot of records at this point.

“And You Must Be This Tall, which is all the other somewhat ‘peculiar’ music that I was recording at the same time I was recording Wing Beat Fantastic, a lot of the songs that were on You Must Be This Tall were at one time or another scheduled to be included on Wing Beat Fantastic, until Scott [Chatfield, Keneally’s manager and executive producer] suggested to try stripping Wing Beat Fantastic down to its essence and not do so many ‘detours,’ which I’m inclined to do. That’s defined a lot of the records that I’ve made: the ‘quick change.’

The detour as destination.

“Exactly! Exactly. And that’s been great fun for me but with the arguable exception of Wooden Smoke, I hadn’t ever made a record that isn’t so jarring. And part of the cohesiveness to Wooden Smoke is just being shorter. Wooden Smoke is 47 minutes long. As soon as you start getting up into the mid-50 minute range and then 60 and 70 and beyond, it becomes harder to sustain a tone in a narrative, cinematic, flowing kind of way. But with Wooden Smoke I kept it down to 14 mainly short songs and 47 minutes and then I pared it down even more for Wing Beat Fantastic. For the first time in my life I produced a record like what I grew up listening to: a 12 song/40 minute album. It’s the first time I’ve managed to be that restrained. But what I found so satisfying about Wing Beat Fantastic was that at 40 minutes I didn’t feel like anything was missing. You’re basking in the experience you’ve just had, and hopefully when you make it from the beginning to the end of the thing, it was a complete experience that brought you somewhere, that kept you engaged, and maybe offered these moments of real surprise and delight.”

*************************

So, Scambot is still planned as a tryptic, right? Three volumes of discs?

“Yeah.”

Can you describe who or what Scambot is?

“Scambot is a guy. He’s a kind of grumpy songwriter whose consciousness is being controlled by a guy named Boleous Ophunji, who’s a billionaire. He owns a jam company; he makes fruit jam. But he’s also an evil genius who has gotten a hold of Scambot’s consciousness and is able to make him behave any way he feels like, usually for stupid and very self-centered reasons; he’s a very self-centered guy. So, Scambot 1 focuses on some occurrences when Ophunji is getting very aggressive about controlling Scambot’s behavior and Scambot gets hooked up with this avant garde musical ensemble called The Quiet Children. And he has a friend named Kootch who’s a rodeo clown — they get chased around the city. There’s another guy who’s a seraph [part-man part-angel] whose name is Govin. He’s chained by the ankle in a cell in Ophunji’s factory, and he uses his consciousness to make musicians play for Ophunji’s entertainment. So, he’s got this weird sort of Roman emperor decadence about him.

“The first album has this very dense narrative and it’s all a bit ridiculous, and the music sort of reflects that. On the second album I want to pare it away to more essential feelings and emotions in the narrative and also in the music. And then on the third volume I want it to get to a nearly meditative state, where it might even be all instrumental, and it attempts to create all of these plot points strictly coloristically, musically — where it’s abstract but still somehow in a Kubrickian way something about the essence, like the last half-hour of 2001 where if you were to describe what happens there in a standard plot manner, you wouldn’t have much to talk about. But to experience it: you’ve been through something, of feelings being created in you, and it leaves you with some impact. Or at least it does with me. So I kind of see that maybe Scambot 3 will be the equivalent of the last third of 2001: A Space Odyssey [laughs], but in a musical fashion.”

That would be pretty amazing.

“I mean, we’ll see… [laughs] But I do want each successive volume of Scambot to feel clearer than the one before, with the idea of honing in on some sort of essential truth about myself and my relationship to music eventually on Scambot 3, whenever that happens.”

When you say things like the ‘Emperor manipulating the consciousness of Scambot,’ it makes me think about the nature of consciousness, which is one of my favorite themes, and how there’s so many mechanisms in the world that are all about manipulating consciousness. The mainstream media is all about manipulation for a seemingly odious agenda. However, by exercising your own creativity that’s how you manage to transcend all of that enculturalization and programming.

“It’s intriguing. I only have my own case to comment on with any intelligence. When I was at a very impressionable and open stage, I started listening to all of this music. In every case it was a reflection of the consciousness: of the message and the intent and the will of the people creating that music.

“Because I spent more time in that realm, that stuff was imprinting on me more heavily than the stuff that was coming over the TV, although the stuff that was on TV definitely had a huge impact because I spent a lot of time in that realm also.

“Basically you have two diametrically opposed systems: the stuff that was coming over mainstream television and the stuff that was coming through this music, which also needs to be said, was coming through mainstream channels: on Reprise Records, on Warner Bros. Records, and RCA Records, these conglomerates. So in some ways the thumbprint was there as well. I got something from listening to what Ray Davies had to say about war on ‘Some Mother’s Son’ and ‘Mr. Churchill Said’ and ‘Yes Sir, No Sir.’ It definitely affected my value system. I remember early on feeling like ‘yeah, that feels wrong, that feels exploitive, and it feels callous the way lives are treated during wartime.’ That sort of human-as-chess-piece mentality was troubling to me early on, whereas other kids my age would have been very happy and went on to join the military and that was their path and what felt right to them. Early on, as a result of the ‘wicked counterculture,’ which was represented on these records, those messages resonated with me more than the flag-waving approach. I don’t know why. It wouldn’t necessarily have been the choice to make, given my upbringing and the communities that I lived in, but it’s just what felt right.”

******************************

In regards to his 53rd birthday this month, Keneally says, “It’s a little weird… and I can’t say that it gets me down overall. There are times, though, where you shake your head, a very basic ‘where did the time go?’ kind of thing. I still feel very connected to things that happened a long time ago, that almost feel as though they happened last week, so it’s just a little bit difficult to grasp: the mutability of time. The fact that it just goes so much faster as you get older just means that the years pile up alarmingly quick. So, it gives one pause, but basically, what the hell are you going to do about it?” he laughs. “You just keep doing stuff.

“I will say where I feel myself in general at the moment is that I have a great deal of work to do with myself. And I have momentary glimpses of ways to deal with it. I’m still very, very much a work-in-progress. I believe that on balance that what I’m offering the universe is helpful. So I continue in my halting way to try to stay on that side of the meter.”

All of Mike Keneally’s albums are available at Exowax Recordings through www.keneally.com.

Mike Keneally’s music streams lives 24/7 on www.radiokeneally.com