Featured Stories

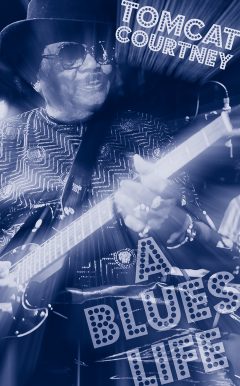

Tomcat Courtney: A Blues Life

Tom “Tomcat” Courtney died last month. He was the Godfather of the Blues in San Diego, and among the last of the OG bluesmen in the world. He was our direct link to Lightnin’ Hopkins, T-Bone Walker, Johnny Shines, Smokey Hog, and all the past greats. He meant so much to so many, and the proof is in all of the musicians in town who revered and respected him. Up until Covid, he still played at least three nights a week…at 91 years old! Tom was not only one of my dearest friends for 30-plus years, he has been one of the most important people in my life since I was 19 years old. RIP Tomcat —Scottie Blinn

Obviously it was a woman that gave him the name Tomcat, and he’s got the scars to prove it. But the man who just celebrated his 87th birthday, surrounded by friends, fans, and some of the best musicians in Southern California, shows no signs of slowing down. His face may reflect a little more wear and tear, but he has the work ethic of a performer half his age. His mind is still sharp, his wit is still quick, and his blues can cut you clean to the bone. Tomcat Courtney is a living, breathing American treasure and has reached the zenith of his genre, that of a revered and respected blues elder.

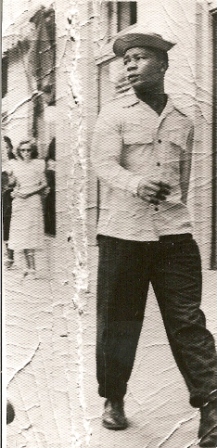

Born in Marlin, Texas in 1929 and relocating shortly thereafter to Downsville, Tomcat is one of the very few surviving bluesmen that grew up in the Texas cotton fields. “That’s what it was,” he says. “I didn’t give it a big thought back then. In ’42, that’s when I left the farm. The same year is when they started drafting everybody into the Army, man, everybody.

Anybody who could walk got drafted into the Army. I was too young.”

Some of Tomcat’s earliest memories are the stuff of legends. Another well known name from Marlin was Blind Willie Johnson? “Yeah, I knowed him,” he nods. “But I was small, you know? I saw him play. I saw Robert Johnson when he was playing in this little old place out in the country. Most of them people played in the fall of the year, when cotton work was plentiful. They had a little change rattling around in their pockets. Back then there wasn’t no money, man. Robert Johnson was playing in San Antonio, Texas and Dallas, that was about 1937 or ’38. Right after that he died, I remember that, heard people talking about it, but I was just a kid about eight or nine years old.”

Who were some of the other musicians you remember from that time?

“Sonny Boy Williamson,” Tomcat says. “My father had a little old joint; it was a barn he made a juke joint out of. Way out in the country you know, it had an old tin roof and when it rained…yaaaaa!!! He laughs, “It was loud, but tin was cheap. But the sound was better or maybe it was me? I don’t know.”

You were just a kid, were you allowed to attend shows at your father’s juke joint?

“Well, they had windows and they opened them up and bolted them up and I’d sit in the window. Especially when Lightnin’ [Hopkins] played. I was more enthused about Lightnin’ than Robert Johnson. I didn’t think about it until years later. Robert was kind of a drunk, he wasn’t jolly… you know what I mean? He played [breaks into song] ‘Went down to the Crossroads, fell down on my knees…’ like tears all the time, but Lightnin’ was jolly. You know the spirit they put into it. I remember that and the boogie he put into it. He had that ‘don-ta-don’ [cadence] to it. He used that quite a bit more than he do on his records, ’cause peoples dancin’.” Tomcat begins to smile as the memories flood back. “So then, when I saw him I wanted a guitar. You see, I had a harmonica, I used to try to blow a harmonica ’cause I saw Sonny Boy Williamson blowing it, you know? [laughing] “He was the first that I saw who sat down and entertained people. He was the best I saw; he talked about so many things, the train… He mostly blowed about lovin’ his woman and kissin’ at night and this and that and makin’ the harp play the thing, make the harp cry.” He sings. “‘Mama!’ and all that, you know?” [He laughs and breaks into song] ‘Now call your mama…Mama, call your mama…Mama!’” [laughing]

How did you acquire your first harmonica?

“My old man got me that harmonica for Christmas or something. But then you could buy a harmonica at Cress’ and all them places, I think they paid like 30 cents or something, a quarter, a cheap one, you know? I blowed the sides off of it and got another one the next year and you know I quit blowin’ that thing for years, but now I blow it now and again at gigs. But after I got a guitar and that guitar was harder to learn than that harmonica. I said, ‘Lawd, I wish Lightnin’ would come back down here.’ So when he did, I said, ‘How do you do that?’” He simulates Lightnin’s style. “De-da-de-dah.

How did you come by your first guitar?

He smiled. “Actually, I got that guitar from a guy who had a garden. Everybody had big gardens and things back then. He had a Stella guitar, the kind Leadbelly and them played, but he had a big, nice one but it had a little hole in it and I said, ‘I sure would like to have that guitar.’ He said, ‘I tell you what, you help me get these weeds outta the garden and I’ll give you this guitar.’ Man, I pulled up every weed out there. I had a pile of weeds that high.” He raises his hand above his head. “He gave me the guitar and I put some old strings on it, and that’s how I started.”

Can you describe the style of blues you play?

“Well, I tell you what happened. After I really started learning the guitar, I kind of started basing it off of Lightnin’ Hopkins. I started singing and playing and wrote a couple of little songs and there was a guy who blowed a horn and he wanted me to play rhythm on the guitar but you gotta learn some chords. I played in G! [laughing] So he taught me a lot of chords and stuff, changes and tuning. He helped me quite a bit on guitar. There was another guy named Charley Lewis, who was the one I really based off of and playing by yourself, the foot thing and all that. He had all that going, man. He never left the farm; he died down there. He was old then, when I was just a kid. He kind of had a style like Blind Lemon Jefferson.”

You saw Tampa Red at your dad’s juke. What do you remember about him?

“He was mostly a singer. I didn’t see him that much because they were mostly in a hurry, on their way to Dallas about 60 or 70 miles from Waco. All they had in Downsville—it was cotton country—was a store or two and a cotton gin and a lot of people came through there on the way to Dallas or San Antone to record.”

Some of Robert Johnson’s most memorable recordings were in a hotel room in Dallas.

“Yeah, some in San Antone and the rest in Dallas. Robert Johnson and Tampa Red were on the same session. People don’t know that, but they were recording at the same time. That’s how they wound up in the same neighborhood. They was in San Antone and then they came to Waco. See, I used to go to Waco; every couple weeks we’d go on Saturdays and I’d see them cats playin’ on the streets. And who inspired me more than all of them, this guy had a washboard. They called him Washboard Sam,” Tomcat recalls. [note: Robert Brown, known professionally as Washboard Sam was believed to be Big Bill Broonzy’s half-brother] “He had a washboard, a guitar, and a harmonica. When that man come around, the police had to move him. He only played in black neighborhoods and streets and they’d block the streets and have to move them ’cause there’s too much traffic.” [laughing] “They’d say, ‘Y’all, l have to move to the next corner ’cause there’s too much traffic.’ [laughing] Them cats would play for tin pennies, nickels and dimes, and a quarter now and then. Them cats were something else, man. They were good.”

It’s my understanding that you literally ran away with the circus?

“You see, right from my house,” he begins to draw out a diagram on the table. “We lived right next to the railroad tracks, and right up here was a cotton gin, the store was over there and the main store was over there where you bought everything. Clothes, groceries, shovels, and picks, like an early Wal-Mart. [laughing] There was a creek and a train trestle. The reason they had a trestle is because they had cows and they would drive the cows across the creek. I used to catch catfish [spreads his hands apart] that big outta that creek. Well, one Saturday we went to Waco and I saw Bojangles dancing. Bill Robinson. You remember these medicine shows; you might have read about them. People selling snake oil, homemade wine, I don’t know what it was made out of.” [laughing] It’s supposed to be medicine, but you’d drink it and get high, and lay down. [laughing] And you didn’t care! [laughing] Anyway, he was dancin’ with one of those things, man. And I would go down to the train trestle and imitate Bojangles every day. I would go down there and imitate the train.” He mimics the sound. “‘Tcha-tcha,tcha…Tcha-tcha,tcha.’ You know the train rhythm? ’Cause there wasn’t nothing else to do, you know? I had my hook in the water and just danced on the train trestle.

Then I got a job tap dancin’ in ’44. Man, I saw a car coming out there, and you didn’t see many cars. And a guy come out there, saying, ‘We’re looking for a kid called Tom, a tap-dancer.’ They wanted to see me dance. Well, at that time my mother had passed and my dad, he was about dead then, you know? I wasn’t nothin’ but a teenager, 15 or 16. Anyway they saw me dance and said, ‘God damn! He can really dance.’ They offered me a little deal of a dollar and a half a night and they’d see after everything. My sister didn’t want me to go. I said, ‘I’m going anyway. They’re going to buy me some clothes!’ (laughing) My sister said, ‘He don’t need to go, he’s too young.’ She made the people sign a statement that they’d look out for me, and they did that. And I ain’t been back there since.”

What circus did you join?

“It was called the Daily Brothers Circus and Minstrel Show. And they used to call me Red Flaps, not Tomcat, when I danced on that minstrel show. They had to learn me how to time-step. They said you had to come out with the group and they showed me and that was it. I was alright by myself.”

Were you playing music during that time?

“No I didn’t play music on the minstrel show. I practiced the guitar but just on my own time. I still had that little old Stella.”

Texas Swing music was all the rage and real popular back in those days; did you ever play that style of music? “When I started in a band, I played up-tempo music and some swing stuff. I just didn’t get into it that much. I was mostly into the boogie style. You know Lightnin’ and John Lee was so prominent and when you go around in those joints in Texas, the juke box had Lightnin’ Hopkins and later on John Lee Hooker. They were just so prominent on the country jukebox. In ’48 or ’49 when John Lee Hooker put out ‘Boogie Chillen’ he’d just about taken over the country blues jukebox. And then Little John Jackson followed about 1950 and put out ‘Rock Me, Baby.’ They all recorded right there together about ’48 or ’49.”

You also knew Ray Charles very early in his career?

“When I first saw Ray Charles all I heard him play was Charles Brown and Nat King Cole. I talked with him and said, ‘Ray, play something different.’ He’d tell ya, ‘Man, I can’t see and I got to live and people seem to like it.’ He said, ‘I got to live,’ you know? He always said that. I was a little older than Ray Charles, about a year. But that sucker, man when I was about 15, me and him started about that age; when I was tap-dancin’ I used to run across him. He was with Lowell Fulson, he had it, man. He had somethin’!”

Let’s talk a little about how you ended up in Los Angeles.

“I was living and working in Flagstaff, Arizona in the late ’50s and playing for lumberjacks,” Tomcat says. “It was nice but in two or three weeks it started snowing. And I was so surprised! [laughing] I didn’t know but Flagstaff was worse than Chicago, man. I didn’t know that. Ain’t this a bitch? And it snowed so bad until everything shut down. Bobby Bland was coming through there on his way to L.A. and Wayne (Bennett) got sick. He was the guitar player, the one on all them records, you know? I had met Bobby Bland in Lubbock, Texas years before. But he said, ‘I gotta’ get a guitar player because Wayne is so sick.’ So, anyway, we went to L.A. and I knew a lot of his songs. He had ‘Further on Up the Road,’ ‘I Don’t Want no Woman Tellin’ me What to Do.’ I couldn’t play it like Wayne, but shit, nobody could play it like that. Anyway, we went to L.A.”

Did you experience any memorable gigs in Los Angeles?

“The Five-Four Club [Ballroom] was closing up. It had been there for years and they were tearing all that out. And before they tore it down they had every band in the world come in to play there for a week. So what happened, B.B., Muddy Waters, Lowell Fulson, Joe Turner, and everybody was playing there during that week, every night. The place was just packed. A big sendoff before it went. They had so many good names, though. They had all the blues players like T-Bone, but T-Bone was living around there then and all the Chicago players. Everybody who had a good name was there.”

So when did you start coming down to San Diego?

“We played down here about three or four times. The first place was called the Black and Tan and that closed, and we played a place right next to it called the Twilight Zone. When I come down here I liked it, but I knew I could get more work in L.A. L.A. and Chicago had more little places you could play in. More after-hour stuff you could get in to. But everybody in Hollywood went there to be movie stars and them that didn’t make it were crooks. So many people went there looking to try to make a living… and so many people went there to be something else. So when I came down here I messed around, I done two or three house parties and had little gigs. I said, ‘Man, these gigs are scarce here’ and I went out to Ocean Beach and there was a place called Peoples in ’69 or ’70. I walked in there and it was a hippie joint. I said, ‘Looky here, man, I’m a blues player.’ He said, ‘I close here on Sunday, I just clean up on Sunday. I’ve got somebody playin’ ‘bout every night.’ Like a folk singer or one or two people and put up a tip jar and a percentage of the bar. And I said, ‘Well, I’ll do that. I’m here.’ He said, ‘Well, if you want to set up and play, we don’t have anyone here on Sunday. And I’d like to hear what you sound like.’ He had a little old PA and I hooked up, had an acoustic guitar, and I miked it up. I just carried that acoustic with me to audition to give ’em an idea what I’m doin’ ’cause when I tell ’em Texas country blues, you know? They want to know what it sounded like. [laughing]

“So I got up there and started playin’ and I saw the guy using the phone. He called like four people and the guys in the back cleanin’ up and he orders some beer. So they got a couple pitchers of beer. Another guy uses the phone and about six more people came. I wind up with like 30 people, man. The guy says this night was better than a week night and they wanna know if I’d be coming back next Sunday? I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll be back next Sunday. The next Sunday it was almost packed and the next Sunday there was people in line and it stayed that way for 15 years. And that’s how I stayed here. It started out as Peoples and a guy bought it and called it the Texas Teahouse. I played there about 24 years, all together. At one place.”

You’ve got to tell us a wild bar or club story before we stop.

“Ah, man, I played in so many places and there were a lot of them. Well, right there in Flagstaff, they started fightin’ them lumberjacks and stuff. The police come in there and almost closed the place up. Man, them dudes be big. I played in places where people were pulling guns and emptied the place. At Peoples one time, a guy come in and cut two or three of us, man. Dude come in there and I think he got four of us, stuck one dude in the side and cut my arm, here. [He points to the scar on his arm] A nut come in there, man, about six or seven years after I started playin’ there.”

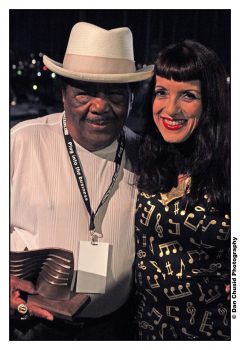

A lot of younger musicians look to you as inspiration and the awards and accolades have come fast and furious in the last 15 years… that must make you feel good?

“Well, I felt all right, but I never paid no attention. I taught a lot of people, but people don’t know it. You know the Mississippi Mudsharks? Scott? Scottie Blinn, he’s such a good guy and I taught him. Man, he can play! The boy can play. When I was at the Teahouse, so many people wanted to learn and I was there for 24 years.”

Longtime friend and fellow guitarist, Scottie Blinn still sits in with Tomcat and shared a few choice memories of the man and the musician. “I’ve known Tom for about 27 years.” Blinn says. “He has my utmost love and respect. I was 19 when I started learning and playing the blues with him—although he’ll tell ya that I was 14. And to this day, when we are in town and have an open night, I’ll still go out and play second fiddle with him. There are so many stories to tell… We had Tom record a song on our second Mississippi Mudsharks CD, Traditional Heavy. He also told stories that we recorded, then interspliced as segues into and out of songs. One story was of a girlfriend he had in Waco, Texas who ran a little house out on the range, and had bought him a Cadillac. One day she got angry with him and chased him through the house with an axe! He jumped out one of the third story window, broke his leg, jumped in the Caddy, and drove as far west as he could… to Ocean Beach. Tom said, ‘Man, that woman was MEAN! She had a graveyard of her own!’”

****************************

Tomcat’s fan base now circles the globe and he starts to laugh as he recalls touring Europe. “Man, that was somethin’ else. I went there a few times, Amsterdam and Switzerland. What happened is I made a CD, Downsville Blues and everybody just dug it over there. Oh, they really appreciate blues, they really appreciate it. Let me tell you, when I got to France I got up and went down to breakfast and all they had was fruit bullshit. [laughing] Looky here man, but when you go to lunch, O-O-O-O lunch and dinner, unbeatable them people’s cookin’. And they got a big thing of wine sittin’ up there. I say, ‘God damn, this shit don’t taste like NightTrain!’ [laughing] They have good wine there, man.”

Amazingly, you still write so much music, nine of the songs on Downsville Blues were originals?

“I just write it… and sing it… shit. [laughing] I saw so many things and lived the way I lived. I went through some hell and stuff, the joints I played.

How do want history to remember Tomcat Courtney?

“I don’t know, man. I think about all these people like Leadbelly, Blind Lemon Jefferson, and T-Bone. I hope they’ll think of me that way: he was a bluesman.”

There’s little doubt about that.

Note: This article first appeared as a cover story from June 2016.