Featured Stories

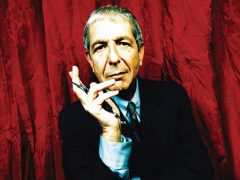

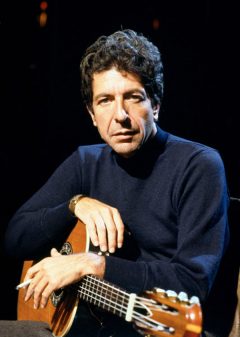

Thoughts About Leonard Cohen

In my mind there was a decades-long debate as to who the best rock and roll poet was: Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen. Being the kind of ersatz pundit who argued passionately for the minority opinion, my champion was Cohen. Critics and audiences and what used to be called Mass Media reached a consensus that gave Dylan the Keys to the Kingdom. All is to say that Dylan has Tin Pan Alley throwing a large shadow over his work. Cohen was part of my teenage soundtrack; the musical commentary in that movie I sometimes imagined would be made about my life. Cohen’s recent passing, of course, demonstrates that he was more than just a short-lived fixture on the album of my life. He was always there, through the years, the decades, making music with every celebration and disaster. Cohen’s music was about growing up and, eventually, growing old. His working premise indicated a desire less to age gracefully than to live fully to the last. This was the rare instance where his work became more profound as I aged–deeper and more nuanced as personal experience matched the literary craft of the songs I admired long and enviously.

His songs made me want to do as he did. I was, though, a callow 17-year-old impatient to grow up and experience heartbreak so that I might wallow in a notion that mine, too, was a life lived fully. In any event, the world that the songwriter laid out in his tunes gave high schoolers much substance to dwell on when our young curiosity turned toward more spiritual and esoteric ideas. Dark rooms full of teenagers, a thick odor of pot and incense, Leonard Cohen’s voice, a rumbling monotone that made you think of a man speaking low or softly who had just then raised his volume enough so that you suddenly heard him speak with alarming clarity of phrase and image and a constant three-chord strum on a guitar. This was my first encounter with the songwriter, an artist who planted the seed in many of us to go into the world and experience it deeply, to contemplate those experiences closely and completely, and to write the inexpressible in terms of the unforgettable. How many of us actually did anything remotely like that is unknown; jobs, marriages, and wars have serious ways of side tracking or eliminating careers as poets. But Cohen managed it in a career that began in 1956 with the publication of his first book, The Spice Box of Earth.

The sacred and the profane were constant subjects in his writing, not so much the arbitrary fusion of unlike propositions mashed together, but rather intermingling the aspects of sensuality and solemnity weaving through each other, elements of the human spirit’s need to experience feel fully alive. Cohen’s chronicle of how he followed his muse over decades–in songs, poems, and novels–reveals a man who, I think, obviously believed in God, a deity, though who might not have a Grand Plan for good people after this life surrenders us to darkness. His Higher Power, though, has a subtle and power sense of Irony. If God is in the details, He is laughing, smirking at least, and wondering what we might learn from the collected experiences that a lifetime accords us.

What inspired the poet in me to come alive and chase the muse of learning how to create suggestive sentences was the expansive flashiness of Dylan’s writing. They were vernacular fireworks that, in their best expression, made no literal sense but still left one with the chilling effect that something was happening that needed a new language to describe the vibe. His songs were public, his lyrics were cast in broad swaths of angular, cubist-bent non sequiturs that were perfect for a generation of youth that vaguely wanted a destiny that would form as all utopias theoretically would, by consensus, without rules, distortions, based on cooperation, in harmony with a natural order that had gotten lost in the rapid shuffle of change since World War II. Cohen was the other extreme, personal, isolated, and reflective to the degree that you felt as though you were invading a private space as you played the albums. It had the effect of walking into a room you thought was empty only to discover someone in there staring into a dark corner of the space, talking to themselves. Cohen felt deeply, considered his affairs, his pilgrimages, and his constant search for experience that might allow him to grow spiritually and so uncover a more profound notion of a love that does not die.

In poems and especially in songs, songs like “Suzanne,” “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” “Hallelujah,” and “Tower of Song,” Cohen comes across as participant and cool observer. Even as his songs’ biographically inspired personas lay their souls bare with nearly embarrassing intimacy, another facet of Cohen’s personality, the poet, the fussy wordsmith, takes stock of each stanza’s events, measures expectations with results and adds the curt flourishes that have always raised this wonderful writer’s lyrics above the merely confessional. There is always the feeling of a man seeking his own idea of truth through the depth of the love he can experience through his wanderings through the world.

He is a pragmatist of the erotic, one could say, entering encounters with full knowledge that each affair and preoccupation are short lived and will add more scars to an already weathered psyche. But this made him richer, he finally thought, better equipped to greet the circumstances of his life in full embrace. This isn’t to say Cohen is philosophically ponderous or didactic. Although his songs are prone to many stanzas, Cohen’s lines and images are crisp, ironic, and demonstrate a masterful use of the snappy line no less agile than what Raymond Chandler’s Marlowe would offer. “Tower of Song,” I think, presents full evidence of this songwriter’s ability to be honest and curtly blunt with his allegories and yet it keep it comical.

Well my friends are gone and my hair is grey

I ache in the places where I used to play

And I’m crazy for love but I’m not coming on

I’m just paying my rent every day

Oh in the Tower of Song

I said to Hank Williams: how lonely does it get?

Hank Williams hasn’t answered yet

But I hear him coughing all night long

A hundred floors above me

In the Tower of Song

I was born like this, I had no choice

I was born with the gift of a golden voice

And twenty-seven angels from the Great Beyond

They tied me to this table right here

In the Tower of Song

In his songs, which I consider the finest of the late 20th century in English–only Dylan, Costello, Mitchell and Paul Simon, have comparable bodies of work–we find more attention given to the effect of every word and phrase that’s applied to his themes and story lines. In many ways, Cohen was a better writer over all. For all his genius and influence, much of what Dylan has released post-John Wesley Harding has been slap dash word-slinging, more prattle than poetry. The contrast with Cohen’s lyrics is remarkable, as there is hardly a careless image, a gratuitous verb, needless intensifier anywhere in his oeuvre. Leonard Cohen began as a writer of books, novels and poems, an occupation performed in isolation where each phrase is contemplated and measured in communicating an emotional architecture. As a lyricist, his bookishness never left him. As a lyricist, he never ceased to be a poet. This cultivated ambiguity that made you yearn for the sweet agony that accompanies a permanent residence in the half lit zone between the sacred and the profane.