Featured Stories

This Is Not an Interview with Gillian Welch and David Rawlings

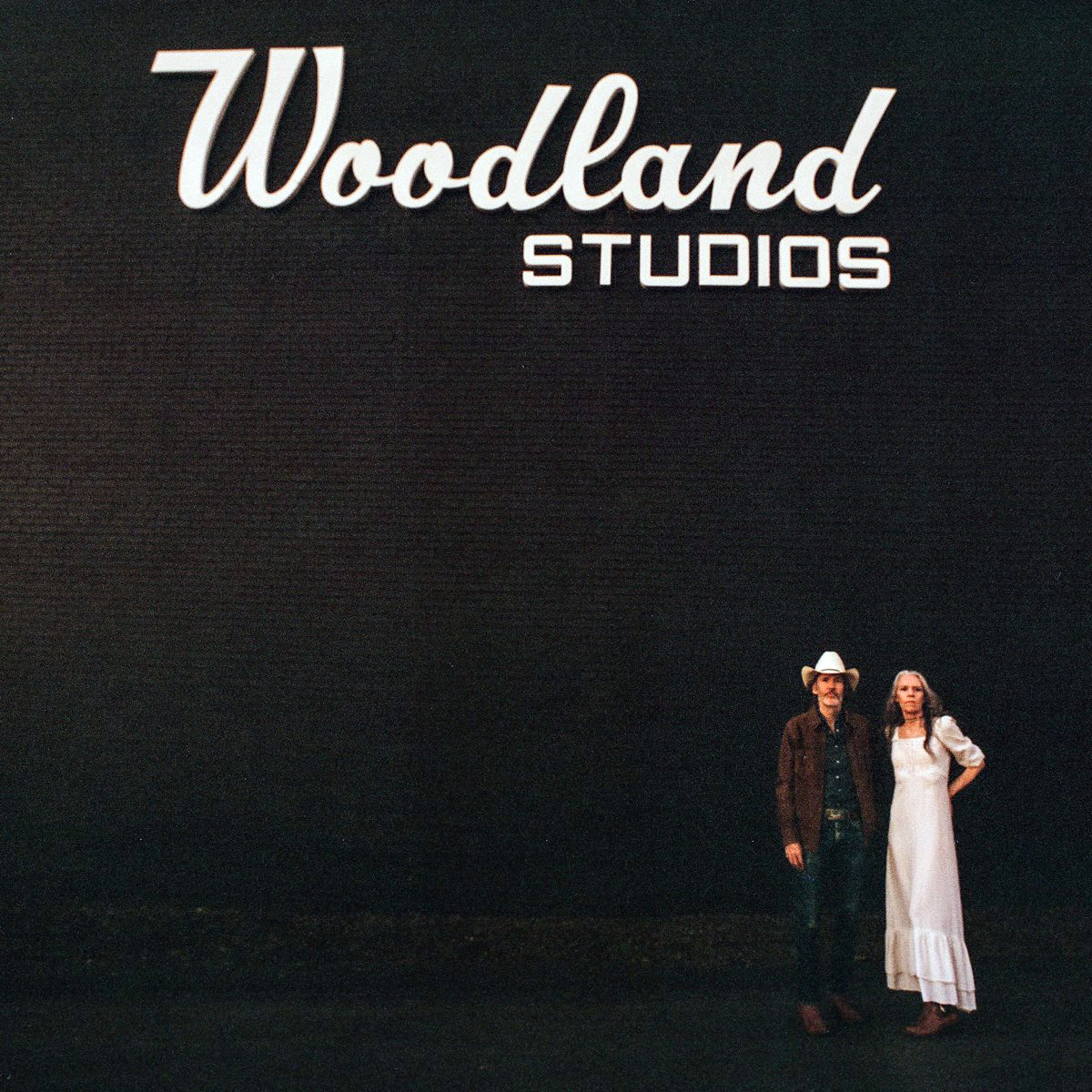

David Rawlings and Gillian Welch. Photo by Alyssa Gafkjen.

It’s been said that a picture is worth a thousand words and by now, there must be a million ways to describe an artist and their music. Still (and I say this as a writer of some experience), words just plain fail to suffice sometimes. Actually, there is one word that kind of covers a lot of ground when we are speaking of the music of Gillian Welch and David Rawlings and that word is “dust.”

I’m not talking about dirt. I’m speaking about the sacred dust of authenticity. A sun-baked patina that covers absolutely everything with arid, acrid, unread hopelessness. Their early songs often felt like antiqued photos in pretty frames…beautiful mementos from a simpler time, with the church-like rural shadings of Appalachia, Texas and the long road ahead. Welch and Rawlings have been digging down deep into the bosom of Americana for over 30 years.

In that time, the duo has released several albums of music together and apart, under their own names or one another’s names. As their discographies have grown, so have the production chops of Rawlings. The two artists eventually purchased a recording studio that had been partially destroyed by a tornado and made it their new creative headquarters. They named their new creative space Woodland Sound Studios.

From the sound of the music (and we’ll definitely be talking more about that), the studio would also seem to feature a wonderfully rare and well-maintained collection of vintage gear. For producer types, even a cursory listen might suggest that a great deal of time and an exacting attention to detail went into the recording of Welch and Rawlings’ latest creation. You don’t just hear all that wonderful dust; you can hear its granules.

Sadly, the Woodland Studio was again destroyed by yet another tornado and these recordings pay homage and testament to the flickering light of human inspiration that can never truly be vanquished by bad luck, misfortune, or even Mother Nature. That album is also fittingly titled Woodland.

The first song and lead single, “Empty Trainload of Sky,” comes on with warm restraint, the two artists’ acoustic guitars setting a wide-panoramic sound stage, at the center of which their voices lock into intimate harmony. All the while, the bass and drums keep gently infusing a softly persistent tension into the vibe. Rawlings plays truly inventive guitar motifs throughout, subtly adding textures like organ and pedal steel and even little shaker eggs to dramatic effect, allowing them to almost seep into these deceptively simple arrangements.

When everything is said and done however, it’s all about the songs and the next tune. “What We Had” is a very formidable contender indeed (despite having a melody very similar to one of Neil Young’s). The bone truth of the song’s chorus relays a message of missed opportunity and remorse.

I used to dream of something unseen

It was something that I thought I wanted so bad

Now I only want

What we had

The lush, aching string arrangement swells mournfully, climbing ever higher with each refrain, as if it were trying to reach the summit of the listener’s feelings and the depth of our regret.

“Lawman” tells a story of surrender and predestined fate:

Now the ground’s gonna freeze when fall is over

Fever gonna burn in a big brass bed

The big iron gonna rust, everything’s dust to dust

Lawman gonna kill my honey dead

Rawlings’ guitar seems to run downhill, its winding figures cascading through the song like a mountain stream, washing over us with a beautiful, if foreboding air of premonition.

The duo bring things into even sharper focus on “The Bells and the Birds,” its tumbling guitar arpeggios and plucked harmonics spinning like airborne carousels as Welch asks,

Listen how the bells ring in the morning

What do they say to you my love?

Some hear a song and some hear a warning

What do they say to you my love?

“North Country” seems to place us in the wheelhouse of the duo’s back catalog, where the style and imagery are comfortably familiar and the message clear and unlabored:

We used to steal away and watch the fireflies after dinner

It’s a slow-motion dream that you never see

Way up in the North Country

The writing is unforced and free of artifice. It describes a treasured time whose minutes are still ticking down somewhere, their words lending a mixture of wisdom, nostalgia, and longing into the mix. The dust mentioned earlier is found within the direct honesty these songs are foundationally rendered from and mired within.

“Hashtag” was written for their friend and mentor Gene Clark, a riff on a joke they shared with regard to the common fate of musicians:

You laughed and said the news would be bad

If I ever saw your name with a hashtag

Mm, singers like you and I are only news when we die

It’s a telling meditation and there is comfort to be found within its acceptance and embrace of life, as well as death. Its a story whose reward is in the telling.

You said time makes the wheels spin

And the years roll out and thе doubt rolls in

In the truck stops, in the parking lots

And the chеap motels

The strings reappear wonderfully, underscoring the question like a road-weary mantra:

When will we become ourselves?

When will we become ourselves?

On “The Day the Mississippi Died,” the bass and drums return, along with banjo and fiddle as a couple takes stock of their failing relationship, eventually throwing up their hands in frustration.

I’m thinking that this melody has lasted long enough

The subject’s entertaining, but the rhymes are pretty rough

So fill ‘em up once again, boys

Fill ‘em up and over the brim, boys

There’s whiskey, but the water’s done run dry

Oh we’re drinking to the end

Of a long, long friend

And the day the mighty Mississippi died

It’s a time-honored sentiment, rendered in a decidedly time-honored style and it feels truly genuine in every way imaginable.

The harmonica-driven “Turf the Gambler” tells the vaguely comic tale of the passing (or possibly not passing) of a poker buddy, in this oddly cinematic ditty.

Rawlings and Welch return to the two voices, two guitars format for the heartbreaking “Here Stands a Woman,”, wherein the protagonist seems to almost apologize to her partner for getting older:

You told me that you loved me

And that would never change

But I’m looking in the mirror

I know I’m not the same

The language is direct and unwavering. You can almost feel her eyes locked in both sincerity and surrender. Elsewhere, she regards life’s impermanence with an air of resignation:

The mother and the father

Who kept me in their care

They’re both gone like the ribbons

That I used to wear

The two performers trade lines throughout Woodland’s final track, “Howdy Howdy,” a tribute to persistence and resilience in a life that’s full of detours.

You and me are always gonna be howdy howdy

You and me always walk that lonesome valley

You and me are always gonna be howdy howdy

It’s a galvanizing musical moment: the two troubadours almost casually reaffirming their commitment to a life lived together, come what may. Considering what has already come their way, I’d say that’s about as strong an affirmation as there is.

Entire publications are devoted to the quest of making recordings that sound like these from Woodland Studios. From a technical, philosophical, and creative perspective, this is as good as it gets.

Gillian Welch and David Rawlings appear Thursday, March 6 at The Magnolia in El Cajon.

Sven-Erik Seaholm is a record producer, singer, and songwriter from San Diego, California.