Featured Stories

Sound Advice: In the Studio with Bob Pruitt

Sound engineer Bob Pruitt in his studio.

It’s said that music can stimulate our brain, change our moods, and spur the imagination. If you were to fuel that creative process with an unlimited curiosity, copious amounts of technical knowledge and then attempt to capture and preserve it all on analog tape; then and only then will you get a sense of the electrical impulses vibrating through Bob Pruitt. Turning a love of music into something tangible has become this man’s art form.

His road as a musician, concert and studio sound technician, and electrical engineer comes from a lifetime of exploration and influence. Tracing his roots directly back to his mother’s piano and his father’s volt meters, Pruitt’s career direction and diversity seemed destined from the start.

As a guitarist, singer/songwriter Pruitt performed and toured so much over the years he says, “It paid for my college degrees.” Those advanced technical skills and qualifications also paid dividends. Bob has worked in both studio environments and mixed live shows with some of the biggest names in blues, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll, from Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, and Albert Collins to jazz great Tito Puente and rocker Joe Satriani to name but a few. And if that’s not diverse enough, Pruitt also taught electrical engineering at the college level for decades and has designed, built, and still runs his own recording studio today.

We started our conversation in Missouri, was it Columbia…Kansas City, where was home?

Pruitt in 2012. Photo by Dennis Andersen.

Well, my real home was more where my family was from; my mom was from Kansas City. She was actually born in Salina, Kansas, and my dad grew up on a farm in northwest Missouri but he got into the Army Air Corps in the ’30s, and we wound up living all over the world. He was in what became the Air Force after WWII. He was a lifer so every three years we moved to another town. Although my family is really Missouri centered, I was born in Puerto Rico and moved to Rome, New York…Tachikawa, Japan, and then in the first grade we were in Realto, California. That’s where I became cognizant of my surroundings at about five or six years old. We lived there for three years, and I grew up thinking what was normal were brown hillsides and red tile roofs and fabulous weather. Then we had the great fortune to be stationed in northeastern France in a town called Laon and I spent my early teens in France, which was a gas. France is great and you learn the language when you live there, and I loved it. Then we were stationed in Madison, Wisconsin which is a cool place, but it was colder than hell in the winter and hotter than hell in the summer. [laughing] When he retired, we moved to northwest Missouri to Maryville, a university town. And that was because dad wanted to put all his kids through college, which he did and that was admirable.”

Were you playing music in your youth?

In my early years I played in bands, starting when I was about 17. But also at that time I got a tape recorder that my brother had sent me from Germany when he was in the Army. Of course, I started fiddling with the tape recorder and my dad’s job in the military was in electronics, so he taught me that stuff when I was in the ninth grade—how to use volt meters, oscilloscopes, and that. And now I’ve got a tape recorder and I’m 17, and the Beatles just came out! Holy Cow!

Was your family musical?

Pruitt in the studio.

My mom was a piano player, and she could sight read; my brothers and I grew up singing and wanting to do music. She taught us how to do harmony together. When we started playing guitar around 1964, we ran across these Beatles songs, some of which were more complex, and I couldn’t figure out the chords. So, I would go down to the music store and buy the sheet music and if I would lay it in front of mom, she could sight read it. [laughing] So we’d sit around and listen to her play it on the piano. Oh, what’s that chord you’re playing, and we could figure out how to transpose it to guitar. My parents were pretty musical, see they grew up in the Kansas City area during the 1930s, and mom lived about 20 blocks south of the jazz district, so she and her girlfriends would walk up there in the afternoon. Think about this, 1932, 1933 at the theaters there, they’d always have a live band that would play before the movies. Some of the bands that were playing…Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, are you kidding? When she was probably 20 years old, she was hearing people like Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Big Joe Turner. So, they had this kind of music on the stereo when I was growing up.

You mentioned you had brothers?

The two guys I used to sit around the piano with my mom were my two younger brothers. I taught them how to play guitar, I learned when I was 16; my brother Dick is three years younger, so he learned when he was 13, and my little brother David was learning when he was 10 or 11. They both grew up to be extraordinary musicians and they formed a band in 1980 that is still together called the Bel-Airs. They play all over the Midwest and they actually lived here in San Diego for awhile. They’re good friends and have toured with Mark Wenner of the Nighthawks out of Washington, DC. I did their very first album at the Land Recording Studio.

Was there a moment in your technical and recording side that you just knew that would be your direction?

The thing that really made me want to be in recording studios was when I was in Realto in the second grade and my older brother comes home with a stack of Little Richard records. WooHooHoo! I heard those records, and something clicked in me. I don’t know what they call this place where that’s going on, but I want to be in the room where they’re doing that!

Spending as much time as you did in and around Kansas City, that part of country is well known for its blues and jazz influences.

Blues, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, country, there are probably 25 active blues clubs in Kansas City and three jams every night, somewhere. Think about that time in the late ’50s and early ’60s, the people that killed me in that era, Little Richard, Richie Valens, the Big Bopper, and, of course, Buddy Holly and Elvis. I think the first one I discovered on my own hanging out at the record store was Roy Orbison, I loved his voice. And just rock ‘n’ roll in general but probably the thing that changed me from listening to just pop music and exploring more blues and R&B was our band getting hired to be in a music festival with Willie Dixon. He was the great producer at Chess Records, and I had the good fortune to mix sound for him at live shows…four times. I love that guy; he was such a lovely man. Our band did a show at this festival right before Willie’s band. I was 19 and I heard this guy up there singing with this fabulous band; it was the lyrics. It was those lewd, double entendres that sucked me in. I heard those songs and said I want to sing music like that! It was way more fun and radical than pop music. And the band, Otis Spann on piano, Big Walter on harmonica, are you kidding me? That was when I was 19 and it changed what I wanted to hear in music. The Bel-Airs, my brother’s band, opened up for Willie Dixon several times around the Midwest and he developed a friendship with Willie. And Willie signed my brother Dick’s Precision bass…Willie Dixon’s signature is on his bass! [laughing]

You had a recording studio in Columbia, didn’t you?

For 15 years, I had a place called the Land Recording Studio; originally it was called Lectric Looney Land but we abridged it and it was officially called the Land Recording Studio. Our band was called Looney Tunes. That was my first studio and that was in Columbia, Missouri.

You worked with a wide variety of artists early on.

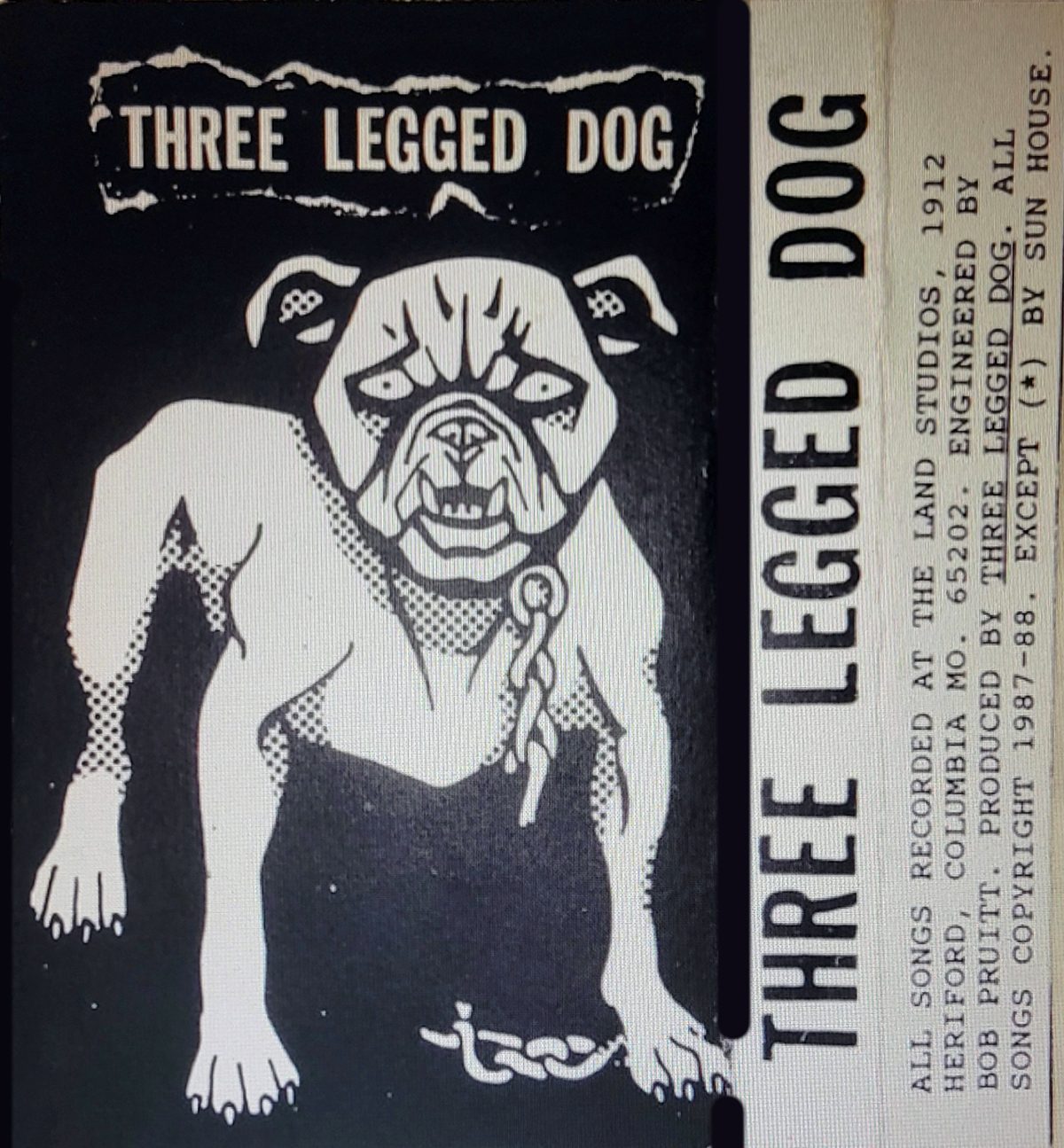

Deke Dickerson became big, and the Bel-Airs have really done a lot. Three Legged Dog and a blind country singer with a group called the Midnight Delights. But it was when I moved to San Francisco that I started recording named artists.

You worked for a number of high-profile recording studios.

The one studio I wanted to go to was in San Francisco—Coast Recorders—because it was one of the few remaining studios built by Bill Putnam. Bill Putnam was the guy who started Universal Studios in Chicago and moved out to L.A. to open up United and Western Studios. Coast was one of the three remaining Bill Putnam rooms and out of the 60 studios that I sent resumes to, Coast Recorders was the only studio that answered my letter. And they hired me, and it was the original Bill Putnam Coast room. It was a killer place, and they were doing recordings for the Concord Jazz label.

You were the house engineer for Coast Recorders and the list of their musicians reads like the who’s who.

Yeah, Ray Brown, Herb Ellis, Scott Hamilton, and Tito Puente, plus some great rock ‘n’ roll folks like Joe Satriani, Chris Isaak, and Edie Brickell.

I moved back to Kansas City and got a job at a studio there called Wheeler Audio and Associates. I also wanted to do some part-time work as a teacher, so I took on a teaching job at Overland Park Community College teaching electrical engineering. It was also around that time I was playing Knuckleheads and playing the clubs around Kansas City with the Blues Demons. I became the Saturday afternoon blues host at Knuckleheads at the Saturday afternoon blues jam. The cool jam in Kansas City is down at the old Black Musicians Hall in the Jazz district. At that jam you could hear people like Kevin Mahogany, Karrin Allyson, and the remaining players from the Count Basie bands.

About how many studio recordings or albums do you think you’ve worked on over the years?

I know, sessions-wise, that I’ve done well over a thousand sessions. I used to do multiple ones every week…for years at the studio. Albums, I don’t know. I’ve probably been involved with over a hundred or so.

You also played in a few bands.

In college one was called Stonehenge, and my band in Columbia was called Hereford Drive. For about eight years, I was touring from Canada to Mexico, from Illinois to Colorado; every Friday and Saturday we were playing another town. It taught me how to play music and I learned about bands on the road, but it also paid for my college degrees. I didn’t have a student loan; rock ‘n’ roll paid for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Are you still teaching?

I retired from full-time teaching in 2018 because I wanted to work in a recording studio again to play music and run a studio. [Bob grins.]

That’s been your road from the start.

I’ve pretty much done both my whole life. Honestly, I feel like I’m walking on a fence, one side of the fence if I fall, that’s the musician and the other side I’m the electronic engineer. I kinda do both…the technical and the musician. I think it’s probably the left and right halves of the brain. It heavily influences what I do technically, because I want it to be very musical.

You’ve worked with so many artists and across multiple genres. Talk about John Lee Hooker.

The legendary John Lee Hooker.

This is so funny… at this one club I used to do sound for they said John Lee Hooker is coming and we want you to do sound for him. In the afternoon I was setting up mikes and things and, at this time, in pop music it was the era when a lot of bands were playing under the name, but you were lucky if any of the original members were going to be there. So, I’m there setting up and the door opens, and this big man walks in, saying “How, How, How!” And I heard that and thought Oh, My God that’s really John Lee Hooker. I ended up doing sound for him probably three or four times; he was extraordinary. The different people I was fortunate to do live mixing for and the one that really sticks to me and that I loved the most was Albert Collins. Wow! What a guy! What a great guy. I was impressed by his flair as a blues musician, his outrageousness, his skill in handling an audience. He was the entire package, electrifying. And another blues guy I was lucky enough to mix for was Albert King.

How did you meet Ray Benson from Asleep at the Wheel?

Asleep at the Wheel’s Ray Benson.

When I ran that studio in Columbia, we had a studio band and there was guy there who was a prolific songwriter. His name was Jerome Wheeler, and he had a band called the Catnip Mouse Band and we recorded Jerome’s songs. He got a gig opening for Asleep at the Wheel in Topeka, Kansas.

It was the middle of the winter, and we loaded up the van and drove over to the big Opera House in Topeka. We set up and played our gig; we did really well because we were so seasoned from working in the studio. But, of course Asleep at the Wheel comes on and they’re fabulous; what a great band. So, we’re packing up and it’s starting to snow pretty good because it’s Kansas in the middle of winter. So, we’re staying at a motel at the side of the interstate there in Topeka, the Ramada Inn. Low and behold, so is Asleep at the Wheel. We discover that the roads are completely impassable due to four-foot snow drifts, and no one can go anywhere so we had to stay overnight and into the next day. The band goes down to the bar to do a little drinking late at night and there’s Asleep at the Wheel down there, too. We hung out with Ray and them at the bar. Years later, I’m in L.A. at the NAAM convention and Ray Benson is at one of the booths. I didn’t think he’d remember me, but I knew he’d remember being stuck in Topeka, Kansas. He says, “Oh, my God, I remember that! I was trippin’ my ass off!” [laughing]

All the people we’ve been talking about and these bands, every one of them were really sweet people. The Asleep at the Wheel folks were wonderful people. The artists that came to Coast Recorders, like Ray Brown, he’s one of my favorite bass players of all time. The first thing he does when he walks into the studio is that he doesn’t walk up to the manager or the engineer or the producer; he walks over to the desk secretary and goes, “Oh Louise, how are you doing? How have you been?” They were just so personable and friendly toward people. The same thing with Joe Satriani and his whole entourage; everyone in the band was warm and wonderful, such caring people. The same with Chris Isaak, they’re nice people to be around and so down to earth.

Talk a little about Gatemouth Brown.

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown

Here is another good rock ‘n’ roll story. I would go out with the Bel-Airs and mix sound for them. One time we went up to Ames, Iowa, and the Bel-Airs were opening up for Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. He was so unique because he’s from Louisiana, but he also lived in Texas so he does Louisiana Cajun fiddle like the best of them, but he also plays rip-roaring Texas blues guitar. So, his sets alternate between fiddle and guitar and he’s great at either one. So, I did the sound with the Bel-Airs and then mix Gatemouth and I’m blown away by him. After his set we’re up in the back room, up in the office with the club owner and the bands. The club owner chimes in and says to Gatemouth. “Hey man, I notice you’re not playing any Muddy Waters songs, what do you think of Muddy?” And Gatemouth says, “That Muddy Waters, you go into a bar feelin’ bad and you hear that music and you come out feelin’ worse!” He then goes, “I play the happy blues.” And he was right, Gatemouth played uplifting stuff. I loved Muddy, he’s probably my favorite of the raw blues players, but that was Gatemouth’s take on it.

When did you get to San Diego?

That was a fortunate thing. At that time, I wasn’t working in a studio, I was working full time as a professor at DeVry University. I taught there for eight years and realized I wasn’t going to get tenure and they could drop me at any time. All the engineers that teach in the United States have a list server that you’re on where you can ask anybody about textbooks or upcoming job openings. One day a job popped up that said we need a professor of electrical engineering at San Diego City College, and they listed off the courses they needed to teach and the degrees they needed to have. And it was exactly me. I came out to interview with them and got the job. I wound up in 2006 teaching at City College for 12 years. It’s a great school. The professor’s there care for their students.

I know you said you’ve retired from full-time teaching, but are you still involved with City College?

Well, they call me up as a design engineer, they have a manufacturing engineering department and they teach assembly line stuff on electronic equipment assembly—circuit boards and electronic products. They have a whole line to teach kids how to do it, but they need a product to assemble. So, the very intelligent head of the department there decided he could attract kids into the department by making guitars. They got together with Carvin and Taylor that have guitar-making routing machinery, so the next semester they teach them how to make guitar amps and they called me in to design a little guitar amp for them.

The Rhythm Jacks (Pruitt second from right).

Billy Lee and the Swamp Critters w Liz Abbott (far right), Troubadour publisher. (Pruitt top, second from left)

You played with a lot of bands out here…the Rhythm Jacks?

That was my first band.

Billy Lee and the Swamp Critters?

Right, I played with them for quite awhile.

Bobby and the Blue Tones?

That was an effort to play more of my own songs, more original tunes.

How did you originally hook up with some of those people?

Well, I used to go to a lot of the jams around town. I think that’s where I met the drummer for sure: Joe Bradetich. And I’ve got to say about Joe is that I listened to a lot of tapes in this business and when I listen to the tapes of the Rhythm Jacks, those drum tracks Joe put down are impeccable; there’s nothing you need to do to them. I met Doug Buchanan, the sax player, at one of the jams. Bassist Dale Earl passed away and that’s when I picked up Doug Pope as a bass player. I met him through the Cajun Band. I met Roger Daschle through the Cajun Band too. Floyd Fronius is an extraordinary fiddle player or violin, whatever you want to call it. I think I heard him around town, just going out to listen to music. I was just amazed at how he played. The last drummer I worked with in Bobby and the Blue Tones is Rich Oberto, who was on the last set of gigs in England. I had been in England three times before with Billy Lee and the Swamp Critters; the people are great and the club scene is great. After being there I wanted to go over with my own band and my own music and to focus on roots American R&B and original tunes.

You had the chance to see Stevie Ray Vaughan early in his career.

Stevie Ray Vaughn

My little brother David had become quite a good guitar player and had moved to Austin and my brother Dick and I went down to visit. David was taking us to all the different clubs in Austin. We went to the Cotton Club and Antone’s, the Hole in the Wall, and all these clubs. This one Thursday night he takes us to this tiny little bar. He says there’s a blues guitarist you’ve got to go hear. We go in this club and it’s really small and we’re the only people there. It was my two brothers and I and his girlfriend…the four of us at a table and a waitress. Up on stage is Double Trouble and Stevie Ray with Johnny Reno on sax. We sat there in that bar drinking beer for two hours and we were the only people in the bar. This guy was incredible and a complete unknown at the time and we walked out of that bar just shaking our heads. I remember us saying to each other, you know I bet you in six months this guy is going to be world-wide. And he was! Six months later, everybody knew who Stevie Ray Vaughan was. [laughing]

What’s the name of your current studio?

It’s called West Land Studio and it’s in honor of the old Land Studio. It’s a full-featured recording studio with an 800 square foot music room so I can take on good size bands, but I offer something others don’t; all the basic tape formats. I’ve got quarter inch, half inch, one inch eight-channel and two-inch 24-track but at the same time with analog. I’ve got 32 channels of digital Pro Tools. So, if you want to do just digital, I can do that. So that’s studio recording, transfers, preservation, and maintenance for your studio.

Where does all the inspiration come from?

A very important source of inspiration for me is my wife, Jeannine. She has to get credit for keeping me up on countless artists new and old and has an enormous knowledge of all the music genres. She knows who plays with whom, who produced it, who wrote the songs, and who they played with before. Jeannine has amassed a massive collection of CDs and vinyl that is my source of inspiration when I learn new songs. She doesn’t play an instrument but when I’m recording a song, I always like to bounce it off her ears to make sure I’m getting it as good as possible.”