Featured Stories

Ragtime and the Golden Age of the Xylophone

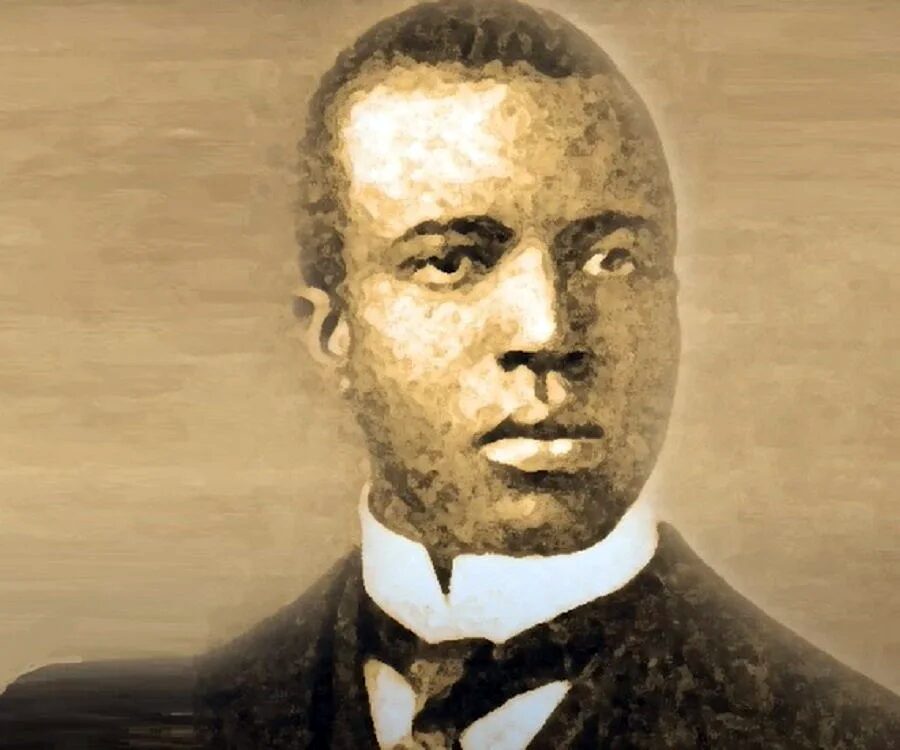

Scott Joplin

When most people think about ragtime music, the first person that comes to mind is usually Scott Joplin, who truly was the king of ragtime music. But ragtime is much more than one person’s accomplishments, even a master like Joplin. In its heyday, ragtime was popular music culture in America. It was everywhere, from the back alleys to boardwalks, equally infiltrating dingy and dangerous saloons to middle-class American homes and even concert halls. Ironically, although ragtime music is upbeat, bouncy, and happy, it could not have existed were it not for one of the most objectionable periods in American history: slavery.

Slaves brought their indigenous musical styles along with them, which included work songs and field hollers. Following a period of acculturation in the New World, spiritual songs evolved and eventually minstrelsy and “Coon” songs were born, the direct predecessors to ragtime itself.

Work songs and field hollers, which can be traced back to the late 17th century, were designed either to accompany the tedium of group labor or to help synchronize the timing of repetitive tasks. Slaves were actually encouraged to sing while working because it increased productivity, which, of course, made and kept plantation owners very happy. Field hollers on the other hand were cries or calls that slaves used while working in the fields as both a method of communication and a means of locating one another. Many slaves, especially those from Africa’s Slave Coast, traditionally used drums to perform this task. However, because they were used to send and receive secret messages, drums were banned from the plantations.

Bert Williams a popular actor during the 1920s, in blackface.

By way of late-night camp and revival meetings, many slaves became Christians and, owing to acculturation with whites and hymnody, soon the African spiritual was born. There were many different classifications of spiritual songs such as sorrow songs (arguably the most famous being “Nobody Knows De Trouble I See”), while more up-tempo songs of jubilation were called jubilees, making up the largest group of spirituals. Regardless of the type, all spirituals dealt with the notion of liberation to some degree. Many of the texts and titles of spirituals made reference to the enslaved Israelites from the Old Testament. Songs such as “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jerico” or “Go Down Moses,” “Tell Old Pharaoh,” and “Let My People Go” were all spirituals that came to both symbolize and parallel the plight of the enslaved Negroes. They also served as emotional nourishment, encouraged positive states of mind, as well as offered hope in light of the terrible conditions American slaves were forced to endure.

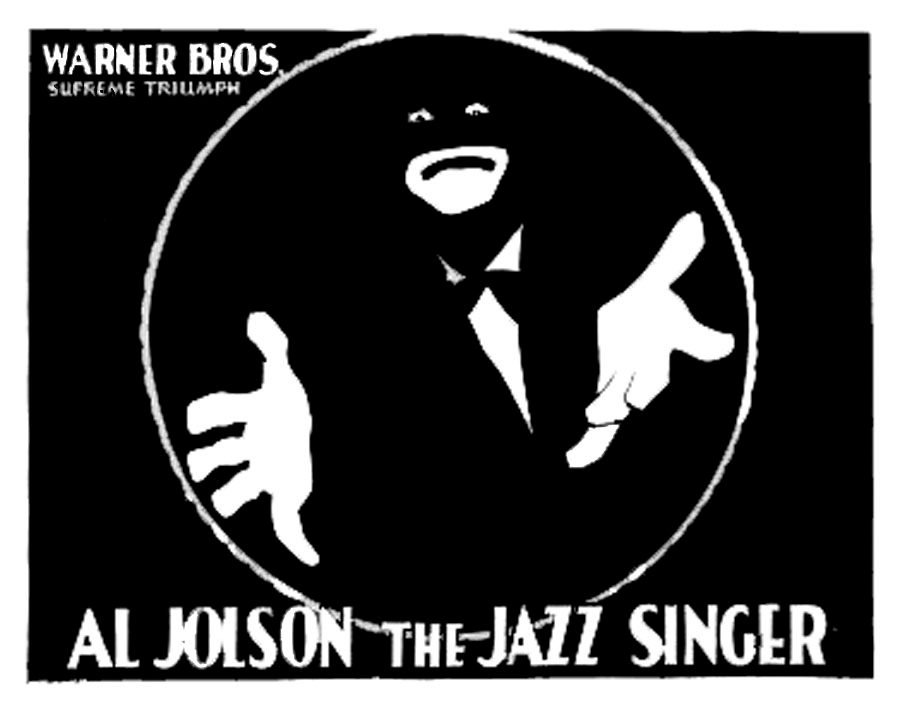

MINSTRELSY

The roots of minstrelsy are as difficult to pinpoint as is ragtime itself. The first documented minstrel show was on February 6, 1843, when four white men performed in blackface and billed themselves as the Virginia Minstrels. Individuals performing in blackface existed in America as early as 1827, but it was the Virginia Minstrels who were the first ensemble to create an identifiable plantation setting through their clothes, makeup, and dialect, which became the framework that turned their individual contributions into a show. Minstrel showmen soon developed certain practices such as performing in blackface made from burnt cork, with exaggerated elliptical mouths outlined in white, and wearing white gloves. Spike Lee’s movie, Bamboozled, gives one a good idea of what a minstrel show was like. The quintessential instruments of a minstrel show were the banjo, the bones, and the tambourine. The show itself would include lively banter, soft-shoe tap dance, banjo soloing, a stump speech (a humorous address by one of the members on a topical subject spoken in black dialect), slapstick, and rousing musical numbers.

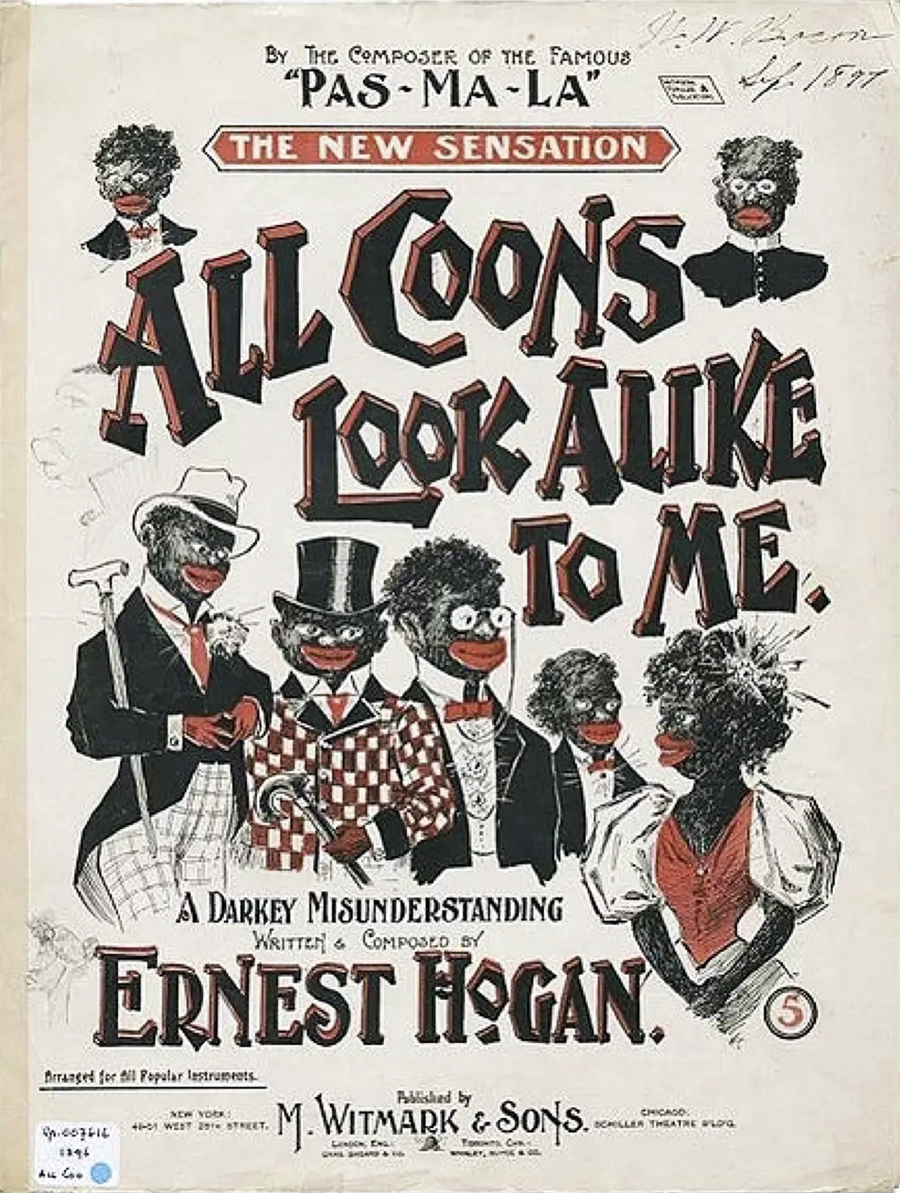

“COON” SONGS AND THE ROOTS OF RAGTIME

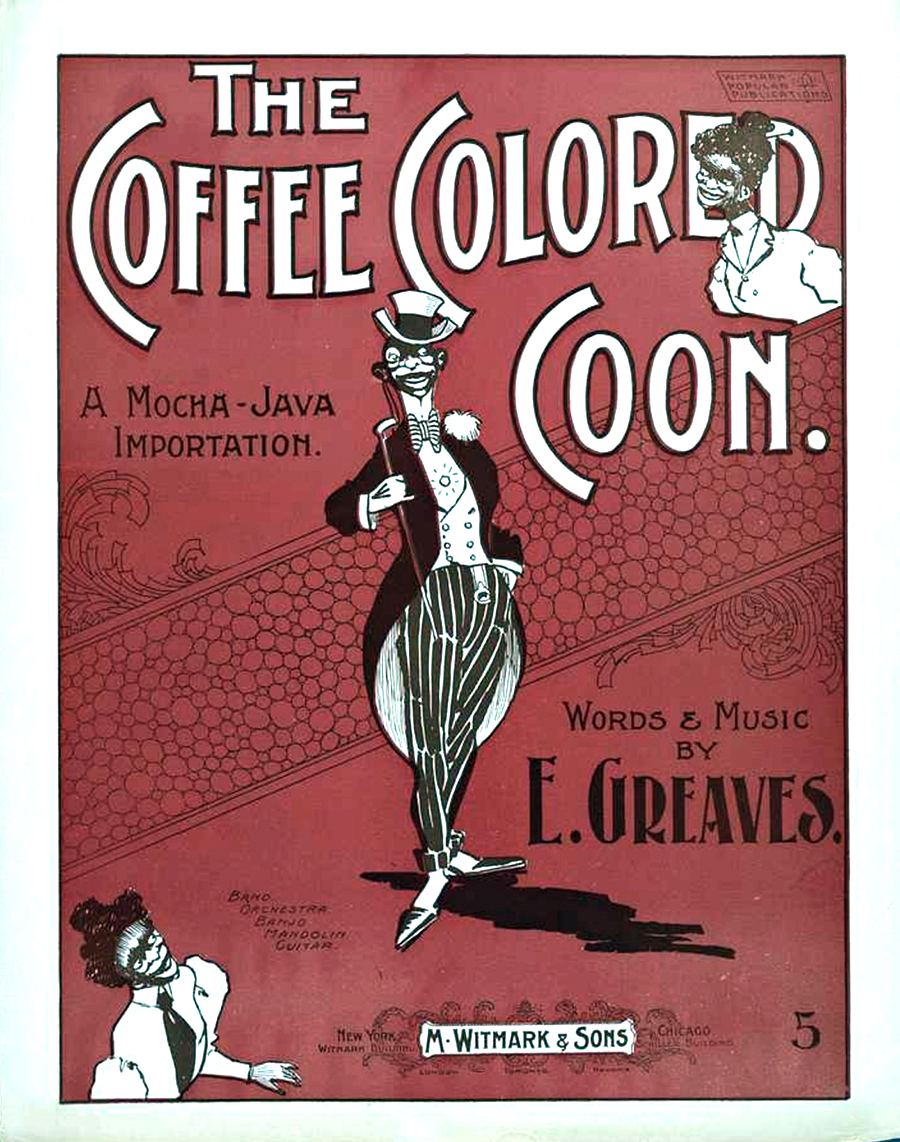

By the 1870s the minstrel show’s popularity was unparalleled in American culture, but it was slowly making a transformation into variety and vaudeville shows by the late 1880s. These types of shows incorporated more visual effects such as slide shows and more dazzling specialty acts like jugglers and tumblers. More important, these shows provided a vehicle for new musical styles, including coon songs and ragtime. It is important to note that coon songs and early ragtime music were seen as the same thing. In fact, Sophie Tucker, usually billed as a “coon shouter” when she appeared in blackface at Pastor’s Music hall, was instead billed as Mary Garden of “Ragtime” when she dispensed the burnt cork but performed the same songs!

The word “coon” itself, from the word raccoon, was a derogatory term coined by whites during the Reconstruction when making reference to blacks. Probably the best known of the coon songs was Ernest Hogan’s “All Coons Look Alike to Me” (1896). Ironically, Hogan, who was himself an African American, did not intend for the song to be racially charged. The song is about a broken love affair in which a woman, who now has a new, wealthier boyfriend, dismisses her old love by saying, “All coons look alike to me.” Hogan, feeling that he had somehow betrayed his own race, died regretting its composition. This song is notable for another important reason—it is the first time the word “rag” appears in printed form. In the published sheet music, an optional arrangement of the chorus states: with Negro Rag Accompaniment. Musically speaking, these songs were characterized by high spirits and rhythmic drive.

There are numerous accounts as to when and how this music became known as ragtime, but it is impossible to know for sure when it was first actually coined. One of the earliest known examples comes in print from 1886, when it was used to describe the rhythm of Negro dance music as “heathenish and ragged.” Another example from the same year came from George W. Cable who described the rhythm of a black dance he saw performed in New Orleans’ Congo Square as “ragged.” Also, in 1888, a Nebraskan banjo player wrote to a banjo music magazine requesting some music with “broken time.” He mentioned that he had heard this music being played by “ear players” (most likely a reference to black musicians who did not read music but played by ear). These examples point toward a syncopated musical style that was understood to have “ragged time.” Hence, it was soon afterward that the shortened term ragtime” was born.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, ragtime music had saturated American popular culture. This new syncopated style of music was infectious indeed! Ragtime, with its African slave roots, was now being played and performed by both amateur and professional musicians alike. More poignant, it had successfully permeated into “white” American culture by way of town bands (Patrick S. Gilmore, 1829-1892, and John Phillip Sousa, 1854-1932, were two such famed bandleaders) and through the manufacture of more affordable pianos. Story-telling, newspapers, and Bible readings were now being replaced by live music in the home where families gathered around the piano.

With the influx of pianos into American homes and the growing number of town bands came unprecedented demands for sheet music. Publishing companies pounced on this demand and made huge money. It is therefore not surprising that piano sales, which peaked in 1909, coincided precisely with the height of sheet music sales. Music publishing companies were releasing the latest and hottest ragtime works just as quickly as they were being composed. Soon after Hogan’s song became popular, the infamous “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899) was published, soon to become one of the highest selling ragtime tunes ever published in America. This work, composed by Scott Joplin and published by John Stilwell Stark (1841-1927) of Sedalia, Missouri, was so enamored by the public that the sheet music went on to sell over one million copies! It is interesting to note that the majority of people learning to play the piano at this time were, in fact, women—usually the daughters and mothers of families who would be taking piano lessons in the home, not the little boys or fathers.

Throughout 1902 most published rags still had obvious references to their black origins and stereotypes, many of which portrayed blacks as stealing, eating watermelon, or even razor fighting. By 1903, there was a 50 percent reduction in black references and, by 1904, less than 20 percent of published rags contained any black references in their titles and artwork. Instead, they showed whites elegantly dressed in tuxedos and gowns dancing in fancy ballrooms.

GEORGE HAMILTON GREEN, NOVELTY MUSIC, AND THE XYLOPHONE’S RISE IN POPULARITY

George and Joe Green.

The era of “novelty” music was fast approaching and the xylophone, which was now being mass produced in America, lent itself well to the added complexity inherent in novelty music. This caused an unprecedented surge in both the demand for novelty music and the xylophone itself. Out of its newfound popularity rose one of its most influential figures, George Hamilton Green, who was born on May 23, 1893, in Omaha, Nebraska into a musical family. A gifted pianist and violinist at an early age, George and his brother encountered their first xylophone in 1901 when George was eight years old. They were so enamored by the instrument that they didn’t stop harassing their parents until they agreed to buy it for them. George made his debut on the xylophone in 1905, with his father’s band in Omaha’s Hanscom Park, playing “American Patrol,” a popular patriotic melody.

Growing up surrounded by music not only exposed Green to the popular music of the day, but it also provided him with a performance outlet. And because of his all-encompassing love for the xylophone, this was the instrument on which he would ultimately leave his musical legacy.

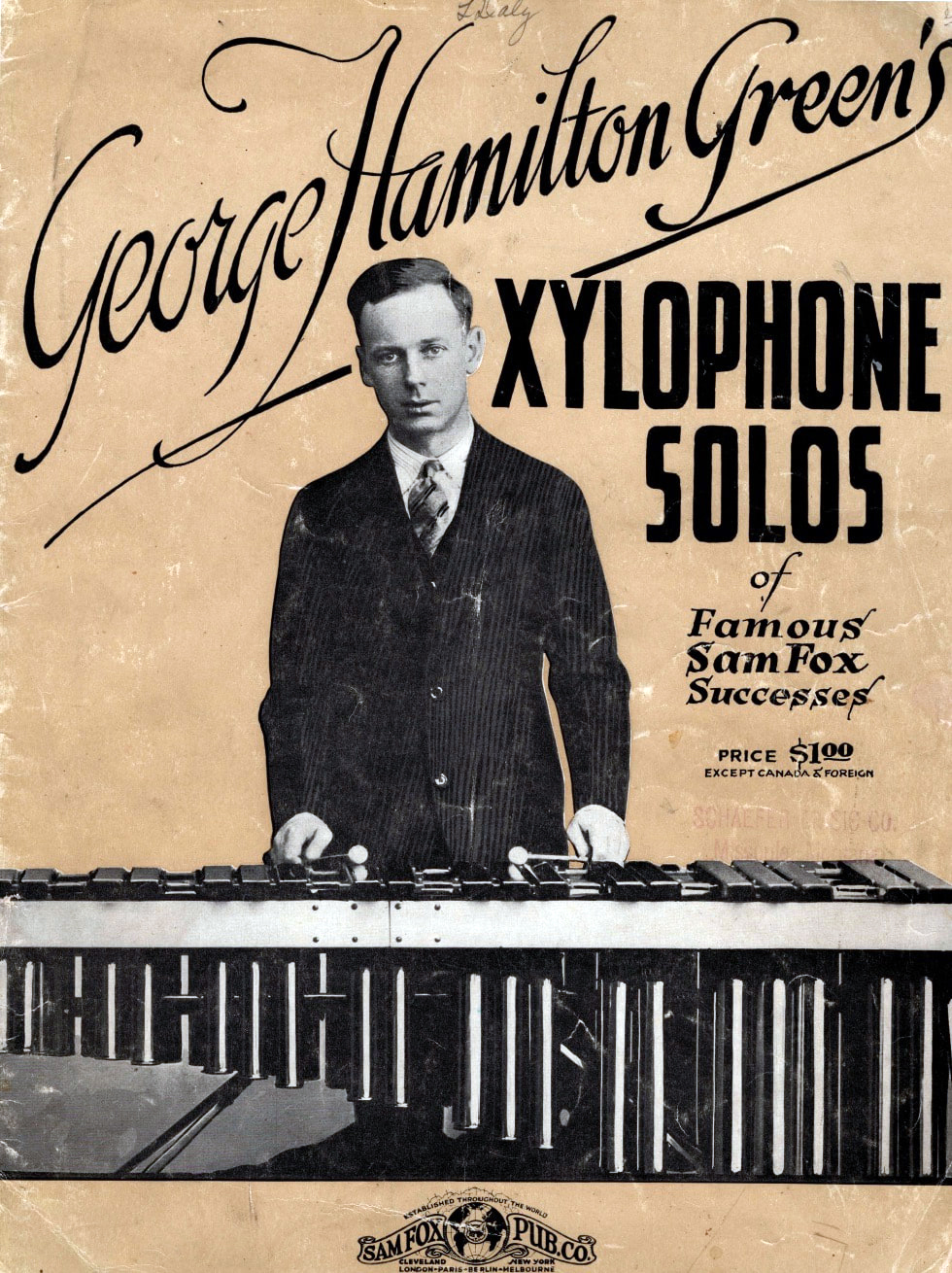

Green’s career as a professional xylophonist can be broken down into three distinct categories: his compositions, his recordings, and, most important, his playing and the development of a xylophone teaching method.

A fascinating history of the Green Brothers.

As it turned out, one of the most preferred instruments to record on early phonographs was the xylophone. Its acoustic properties and articulate nature produced clear recordings for the acoustic phonograph. Although there were other xylophone players hired by record companies, it was George Hamilton Green who was recognized as the greatest of them all.

In 1917, Green made his first xylophone recording for the Edison Company. The end of World War I one year later sparked a dance craze bent on sweeping the nation. The Allies had won, and the boys were coming home. Being in a mood to celebrate, America would see an explosion of both live and recorded dance band music between 1918 and 1925. George Hamilton Green recorded literally hundreds of works in addition to playing in various groups with and without his brother Joe. One particular group, the Green Brothers Novelty Band, recorded frequently over the course of the next two decades and ranged in size anywhere from eight to 16 members with up to three xylophone players! During the 1920s xylophone/marimba bands became very popular, and the Green brothers’ amazing talent on the instrument won them a broad spectrum of fans.

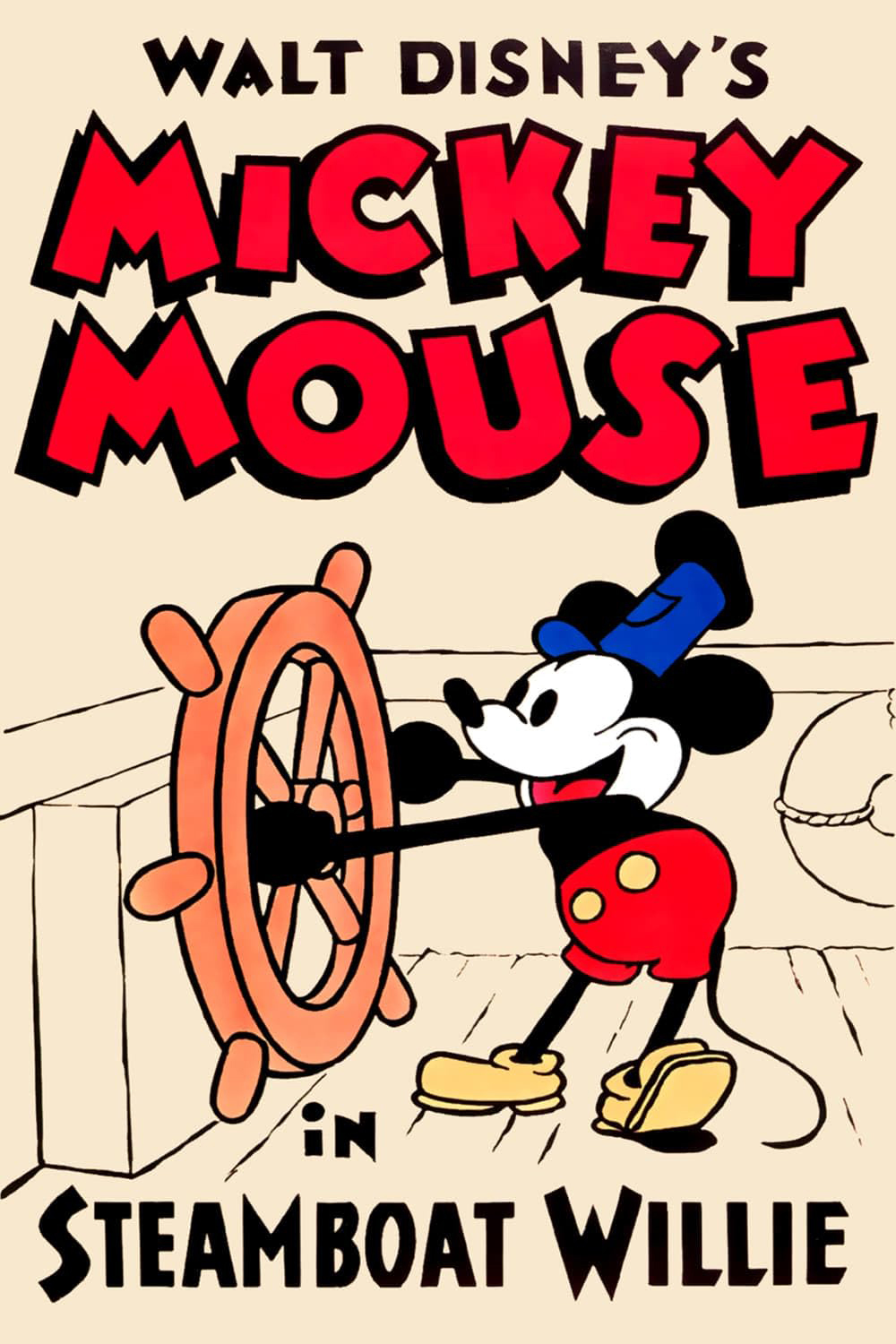

The Green brothers recortded the music for Steamboat Willie as well as two other Disney films.

In addition to recording, Green made many live radio appearances including many on famed bandleader Paul Whiteman’s radio show. A little-known but interesting tidbit is that, in 1927, George and Joe were joined by their youngest brother Lewis (1902-1992) and made history recording music for “Steamboat Willie,” “the Opry House,” and “Skeleton Dance,” Walt Disney’s first animated sound cartoons—a wonderful slice of American music history!

By the mid-1920s few composers wrote purely ragtime pieces. Jazz music was slowly replacing ragtime as the most popular musical style in the U.S., and composers were adjusting to this phenomenon. The influence of blues, when used in a ragtime tune, was clearly audible. Jazz, on the other hand, was what ragtime itself was developing into. It was during this cross-over period that novelty music emerged.

Novelty music included all of the rhythmical elements now found in ragtime music and blended them with chromatic runs (playing side-by-side notes up or down the instrument) and quicker tempos. A more developed harmonic structure formed the overall basis for this novelty music. It was within this period that Green wrote many of his compositions including “The Ragtime Robin,” “Cross-Corners,” and “The Whistler.” The covers for these xylophone solos read “George Hamilton Green’s Jazz Classics for the Xylophone: A Series of Modern Ragtime Solos with Piano Accompaniment,” reflecting the ambiguity surrounding the popular musical genres of the time. The fact that these compositions are still performed by percussionists today attests to both their longevity and creativity. Much of this can be attributed to percussionist Bob Becker (NEXUS, Steve Reich Ensemble) who single-handedly resurrected these tunes in the 1970s by making arrangements of them for percussion ensembles.

Ad for Edison phonographs.

Perhaps Green’s greatest contribution was the development of a systematic study for the xylophone and, with it, the subsequent awareness he was able to bring to the popular music styles of his time. In 1922 George and Joe Green published Green Brothers Advanced Instructor for Xylophone. Still considered standard practice for modern day percussionists, the playing techniques included were not only revolutionary, but it also speaks to the love and understanding both brothers had for the xylophone. What makes this book truly amazing is the level of detail that the Green brothers offer with respect to every aspect of xylophone playing. In 1923 it was George who went on to publish 50 individual lessons, available through mail order, called George Hamilton Green’s New Instruction Course for Xylophone: A Complete Course of Fifty Lessons. This course of lessons focused on a systematic way of applying proper playing techniques to popular music forms, something that was not as thoroughly addressed in the earlier Green Brothers method book.

In 1926, Green followed up his book of 50 lessons with New Series of Individual Instruction Courses for Xylophone and Marimba, providing the tools for learning how to improvise existing melodies. The two books were and still are regarded as the best resources for becoming a better two-mallet player. Although Green revolutionized the way percussionists would forever play the xylophone, he was also interested in creating skilled ragtime players. Although books had already been published that dealt with improvising techniques for the popular music of the day (probably the earliest being Benjamin Harney’s Rag Time Instructor, published in 1897), Green’s was recognized as one of the first to do it during the ragtime/novelty/early jazz era. That Green used the xylophone to apply his methodology to improvisation is secondary; it is the message, not the means.

When one takes into consideration all of Green’s achievements regarding the xylophone within the context of the ragtime music era, it is impossible to deny the impact that ragtime music had on Green or Green’s contribution to the mainstreaming of ragtime music. It is ironic, however, that Green was much more interested in demonstrating to the world that the xylophone was a noble instrument than he was in trying to mainstream ragtime music or become one of its greatest performers. That he achieved both was a byproduct of all his endeavors relating to the xylophone itself. For all the ragtime music he engaged in playing, he performed and recorded an equal amount of arranged classical repertoire. He was even a big proponent of Bach’s Two-Part Inventions, which he would have his students practice, demonstrating that Green thought of himself as a musician (who utilized the xylophone) before considering himself a player of any specific genre of music.

When all was said and done, what Green was most interested in accomplishing was proving to people that the xylophone was capable of realizing a wide variety of musical styles, no different in many ways than the piano. During a 1925 clinic he held in Boston, Green commented on how one should keep the mallets low to the instrument to create a greater degree of accuracy for hitting the correct notes. As it turned out, a few vaudeville players in the audience felt that the job of the xylophone player was to put on a show for audience members—to play in a flashy manner by bringing their mallets high up in the air. Green had no interest in that sort of playing. Green was serious about the xylophone—it was not a gimmicky instrument to him. Rather, he believed it was a versatile instrument, capable of being used in any sort of musical situation, and he spent his professional musical career trying to show this.

Ultimately, it seems that the world did not feel the same way. As technology increased with the advent of the electronic microphone in 1926, the demand for xylophone recordings decreased. Early jazz music was on the rise and the vibraphone eventually took the place of the xylophone in most jazz orchestras. Green also soon found himself losing students to World War II, and many of his network radio concerts were being replaced by newscasts.

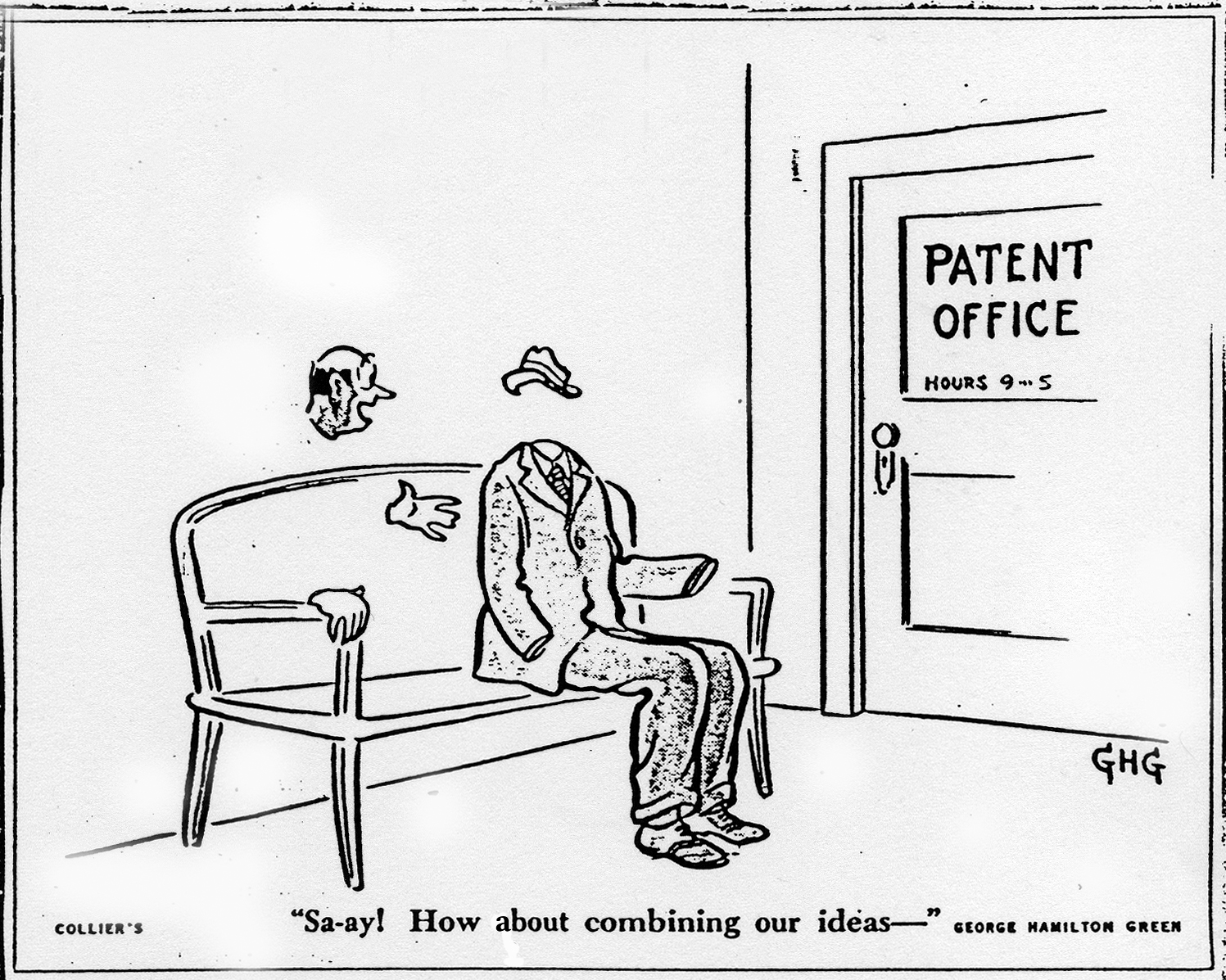

One of George Green’s cartoons following his retirement from music.

George Hamilton Green’s exit from professional musical life has taken on mythic proportions when it was reported that in 1946, during a break in recording from a studio session, Green apparently laid down his mallets and walked out of the studio, never to play the xylophone in public again. Harry Bruer, a famous mallet player in his own right, who was on that same session stated, “He didn’t bother to take his instruments with him, because he knew that he wouldn’t be needing them anymore.” After Green’s untimely retirement, he went on to a successful career as a professional cartoonist, selling his cartoons to such reputable magazines and newspapers as Collier’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and Life.

George Green died on September 11, 1970 and was posthumously inducted into the Percussion Arts Society Hall of Fame in 1983. To this day percussionists worldwide perform his compositions, helping to both promote the xylophone and to keep the wonderful music of the ragtime era alive.

Reprinted from the May 2005 issue of the San Diego Troubadour.