CD Reviews

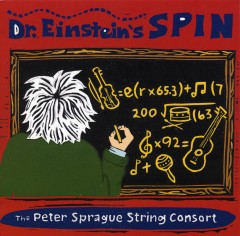

PETER SPRAGUE STRING CONSORT: Dr. Einstein’s Spin

Musical instruments have a funny way of getting stereotyped: banjos are mostly used for playing bluegrass, French horns for classical.

And yet, an instrument is merely a tool. Maybe that’s why some of us get excited to hear John Clark play jazz on his French horn, or Béla Fleck tackle anything and everything on his banjo. And why we delight in hearing Yusef Lateef and Paul McCandless take the marvelous oboe outside its usual symphonic setting.

It’s also why fans of local jazz guitarist Peter Sprague should check out the second recording of his String Consort, Dr. Einstein’s Spin, with the sound of cello, viola, and violin joining Sprague and his longtime associates, bassist Bob Magnusson and drummer Duncan Moore.

Drawing from the same wellspring as his more familiar jazz and Brazilian music playing, Sprague’s work with the string consort isn’t in the realm of traditional classical. It’s closer to what Edgar Meyer did in his Appalachia series of recordings with Mark O’Connor and Yo-Yo Ma: mixing and melding classical influences and instrumentation with jazz, popular,

and rock to achieve a kind of modern chamber.

The album’s title is taken from a three-movement piece about the good physicist. The first movement, “Molecules,” is inspired by Einstein’s early contemplations about the nature of the universe. It is the most modern of the suite, and Sprague utilizes the consort most fully here — creating a sense of motion and energy, with the violins set off against the viola, cello, and bass.

The second movement, “Rainbows,” is, according to Sprague’s liner notes, an illustration of what a relaxing day off might have been like for Einstein. This struck your listener as the least interesting of the three movements, although also the most lush and melodic. While very pretty, it seemed almost a let-down after the creative pell mell of “Molecules.”

“The Expanse” is Sprague’s attempt to capture what it might have felt like to get inside Einstein’s head as he thought about the universe. Sprague avoids the temptation for sweeping musical panoramas or grand thematic statements — instead, it has the same kinetic impulse driving as “Molecules” did, but in an even less linear vein. The lead bounces around the way ideas must have in Einstein’s cranium, and Sprague does a really neat job of pitting the different instruments off one another to create a sense of creative tension.

The opening track, “Mundaka,” is a paean to a surfing spot in Spain, which Sprague has yet to visit. It’s the closest to Sprague’s Brazilian-themed jazz familiar to most listeners. The album closes out with “The End of the Internet,” which is a nice coda to the Einstein suite — modern, uptempo, bright.