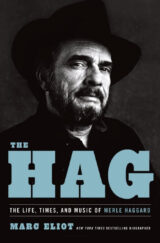

Featured Stories

Our Redneck Poet, Merle Haggard

Book Review

It is sometimes difficult to place popular musicians in a larger cultural context, and this was not the goal of Marc Eliot’s The Hag, an impressively thorough biography of country music icon Merle Haggard. Fans of Haggard—who died in 2016 on his 79th birthday—or country music generally will enjoy The Hag as a celebration of Haggard’s contribution to the “Bakersfield Sound,” a distinctive variation of a genre typically associated with Nashville. Readers may balk at Eliot’s comparison of his subject to Robert Frost, Frank Sinatra, Bob Wills, and Bob Dylan, but they will emerge with a deeper appreciation for a musician who is often undeservedly overshadowed by crossover artists such as Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, and Waylon Jennings.

Haggard was undeniably authentic. His parents were Okies who fled the Depression-era Dustbowl for California’s lower San Joaquin Valley. Left fatherless at age nine, Haggard grew up poor in a converted railroad car alongside train tracks in a town near Bakersfield. Always a rebel and never a good student, Haggard was a chronic truant and serial runaway. Beginning as a boy, he would ride the rails by hopping passing freight trains. A self-taught guitarist who preferred music to books, Haggard loved listening to Lefty Frizzell, Jimmie Rodgers, and Bob Wills. Unfortunately, a rash temper and poor impulse control led to many encounters with law enforcement—and periods of incarceration—even as a juvenile. By the age of 20, he was a convicted felon, serving time in San Quentin prison for armed robbery.

Many country musicians would pose as outlaws, and Cash famously performed at San Quentin (with Haggard in the audience), but Haggard was the real thing. Despite these inauspicious beginnings, within years of his release on parole from San Quentin in 1960, Haggard changed direction and became one of the most successful country musicians in the country. (California Governor Ronald Reagan issued Haggard a full pardon in 1972.) In the following decades, Haggard released over 100 albums, recorded more than 600 songs (250 of which he wrote)—many of them hits—toured extensively, and won numerous awards, including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006 and the Kennedy Center Honor in 2010 (along with Paul McCartney). Haggard even made the cover of Time magazine in 1974, the first country musician to be so featured.

In the late 1960s, Haggard’s gritty, unadorned approach to songwriting—in contrast to the more mainstream “countrypolitan” sound then coming out of Nashville—attracted the attention of influential musicians such as Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards and country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons.

By 1969, America was fraught with cultural turmoil. The so-called hippie movement was in full bloom, as were anti-Vietnam War protests and campus unrest. The Psychedelic Sixties or Age of Aquarius peaked with the Woodstock Festival. Never before had one generation been in such a state of rebellion against its elders. “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman warned.

Following in the path blazed by fellow Bakersfield denizen Buck Owens (whom he ultimately eclipsed), Haggard appealed to an audience made up primarily of middle-class adults with blue-collar or rural roots. This audience—sometimes described as rednecks—was patriotic, conservative, and old-fashioned. In 1969 Haggard released his (arguably) most famous song, “Okie from Muskogee,” which became the anthem for America’s embattled Silent Majority and endeared him to President Richard Nixon. Haggard claimed that the song was a tribute to his father, a failed farmer who grew up near Muskogee, but the lyrics resonated more widely:

We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee

We don’t take our trips on LSD

We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street

We like livin’ right, and bein’ free

We don’t make a party out of lovin’

We like holdin’ hands and pitchin’ woo

We don’t let our hair grow long and shaggy

Like the hippies out in San Francisco do

I’m proud to be an Okie from Muskogee,

A place where even squares can have a ball

We still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse,

And white lightnin’s still the biggest thrill of all

Haggard doubled-down the following year with the equally pugnacious hit “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” which warned:

They’re walkin’ on the fightin’ side of me

Runnin’ down a way of life

Our fightin’ men have fought and died to keep

If you don’t love it, leave it

Let this song that I’m singin’ be a warnin’

When you’re runnin’ down our country, hoss

You’re walkin’ on the fightin’ side of me.

Haggard was far from a one-trick pony. He had 38 Billboard No. 1 hits. His catalog of songs over the years covers the gamut of eternal country themes: drinking (“The Bottle Let Me Down”), hard living (“Swinging Doors”), prison (“Sing Me Back Home”), bad choices (“Mama Tried”), romance (“Today I Started Loving You Again”), loss (“Silver Wings”), poverty (“Hungry Eyes”), trains (“No More Trains to Ride”), struggle (“If We Make It Through December”), and odes to the working man (“Workin’ Man Blues”), rural life (“Big City”), and free spirits (“Ramblin’ Fever”). His duet with Willie Nelson covering Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty” is an all-time classic.

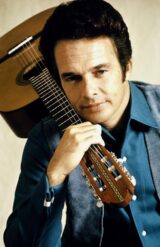

Haggard early in his career.

Yet, despite good looks (Haggard bore a striking resemblance to James Dean as a young man), a beautiful singing voice, instrumental skills, stage presence, and prolific songwriting, Haggard never generated the broad appeal of other artists, such as Elvis Presley’s movie success, the television audience of Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, or Roy Clark (via Hee Haw), or the multi-generational popularity of Kris Kristofferson, Bob Dylan, country-rock groups such as the Eagles, and even Dolly Parton. Eliot does not explicitly spell out an explanation, but the reader can form some conclusions from the abundantly detailed factual recitation in The Hag. Many artists are haunted by demons, which inspire their creativity, and this was certainly the case with Haggard, but those same demons sometimes hindered his success.

Several factors may have contributed to Haggard’s limited appeal. Haggard’s middle-class/blue-collar identification cemented his popularity with that demographic, while alienating him from a broader, younger audience at a critical point in his career. He later toured occasionally with Bob Dylan and appeared at festivals with Willie Nelson, but he always retained his image as a conventional country music artist rather than a hybrid or “outlaw” (although he was once an outlaw). He never grew his hair long a la Willie Nelson, and his beard, by the time he sported one, was not uncommon among country musicians.

Haggard’s old-fashioned song lyrics and his troubled, libertine personal life may strike some as hypocritical, but they reflect the tensions inherent in the generational conflict that roiled the nation during that period.

His stage presence did not translate to the movie (or TV) screen, although he tried. He was headstrong and independent enough to refuse an invitation to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1970 due to his disagreement with the format. He also declined a role in the 1977 blockbuster Smokey and the Bandit.

Haggard (2nd from left) with Johnny Cash, Buck Owens, and Glen Campbell, mid-1970s.

Haggard’s career was not enhanced by an undisciplined and tumultuous personal life. An inveterate philanderer, he was married five times; to the extent that his songs addressed cheating and heartbreak, he was projecting. He also drank, gambled, smoked cigarettes (likely contributing to his eventual heart disease and lung cancer), abused cocaine during the 1980s, and at least by the late 1970s was a closet marijuana user—claiming that his doctor recommended it! Ironically, his felony record was off-putting to some traditional country fans, while—unlike Willie Nelson—he kept his drug use private for many years even though it may have widened his youth appeal.

Early on, Haggard had chosen his cultural “lane” and had to live with that. He was “old school,” and loved traditional country music performed by conventional-looking musicians. Haggard declined to play on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken? project because they were “long-hair hippie types.” Haggard never managed to bridge the “generation gap,” and barely tried.

Haggard was a complex figure. He loved traveling on his bus, which reminded him of riding in a freight car. (He had a life-long fascination with trains.) Unlike many other major country artists, he avoided living in Nashville; he valued his privacy and preferred living in remote parts of California—sometimes on a houseboat. He was a loner, despite his numerous marriages. Even his band was called “The Strangers.” Stubborn and independent-minded, he was not temperamentally equipped to be “directed,” as Colonel Tom Parker had done for Elvis and as Brian Epstein did for the Beatles. He had limited business acumen and made his share of bad decisions, resulting in IRS problems and a bankruptcy in 1992. Nonetheless, Haggard—contradictions and all—was true to himself and managed to achieve remarkable (albeit cyclical) success despite his humble origins, troubled past, and self-inflicted obstacles.

Eliot, who previously wrote a best-selling biography of the Eagles, The Limit (1998), among many other books on popular culture figures, displays considerable familiarity with the music industry, and his detailed book will be of great interest to fans of Merle Haggard or the country music scene in the decades from 1960-2000, the arc of Haggard’s career. Moreover, the life and times of The Hag are illustrative of larger cultural themes that shaped America during that era. He was the voice of blue-collar America during a difficult, disruptive epoch, the informal poet laureate of the nation’s middle class—the working man’s Robert Frost.

The duality between Haggard’s old-fashioned song lyrics and his troubled, libertine personal life may strike some as hypocritical, but it reflects the tensions inherent in the generational conflict that roiled the nation during that period. Poets invoke the readers’ deeply held sentiments and attitudes. Artists convey images and do not pretend to be exemplars. Storytellers entertain the audience with myths and fables. Haggard was a poet, artist, and storyteller—not a preacher. He gave voice to what middle America was feeling without pretending to be a model citizen himself. Musicians are rarely saints, and Haggard was no exception. Many country musicians died young of alcohol abuse or drug overdoses, including Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, and Keith Whitley, but Haggard was a survivor.

That the son of an Okie and an ex-con who served time in San Quentin could count as fans U.S. Presidents as diverse as Nixon and Barack Obama demonstrates the power of redemption in this resilient country. Only in America.

Merle Haggard had a distinct cultural lane that he stuck to: patriotic, conservative, and old-fashioned.

Mark Pulliam writes from East Tennessee. A big law veteran, he retired as a partner in a large law firm after practicing for 30 years. A contributing editor to Law & Liberty since 2015, Pulliam also blogs at Misrule of Law. He considers himself a fully recovered lawyer.

The San Diego Troubadour would like to thank Law & Liberty for permission to reprint this article.