Featured Stories

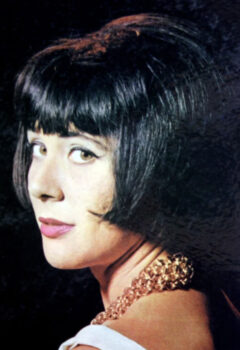

Judy Henske: A Remembrance

“To change the world, you’ve got to be really depressed,” singer-songwriter Judy Henske once told me. “You have to have an attitude that things are really bad, and we have to change them. But I kept cheering up all the time.”

When Henske was a rising folk music icon in the early 1960s, folkies were supposed to be serious, politically committed, and bent on improving the world. Judy took a different path. Instead of protesting the social ills of the moment, she was stomping out the blues on stage, literally pounding her foot into the floors of coffeehouses until the boards cracked. She sang bawdy songs, children’s ditties, murder ballads, mystical lullabies, but no topical tunes. Judy Henske was of her time. But somehow, she was also beyond it.

Judy was a friend of mine for 26 years. When she died on April 27 at age 85, she left behind her a remarkable legacy of music, writing, and storytelling. Her talent, wit, and kindness had earned her a fiercely loyal circle of friends over the decades. Woody Allen (who used her as his model for Annie Hall), Pauline Kael, Eve Babitz, and Shel Silverstein were among those who fell into her orbit. Judy was hilarious, insightful, amazed at the weirdness of the world, and forgiving of its imperfections. She was no Pollyanna; she could be a wicked-smart critic who hated phoniness and slipshod thinking. But more than anything, she liked to laugh at absurdity, and that included the twists and turns of her own career.

San Diego was an early and crucial stopover on her meandering journey. She came to town in 1958, an ex-college student from Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, armed with a banjo and an urge to sing. Judy loved the freedom of the local lifestyle and quickly fell in with the local beatnik scene. The Zen Coffee House and Motorcycle Repair Shop near the corner of Broadway and India Streets became her favorite hangout. There, she mingled with ex-cons and SDG&E employees while she developed her performing skills. At first, she sang in a high Joan Baez-y voice that she came to despise. Judy wanted something gutsier, more expressive. She began to take on the earthier tones of singers like Odetta and Mahalia Jackson as she roared out folk and blues material to espresso-sipping audiences for five bucks a night. Judy was brassy, but she was also brainy—no blushing damsel, she became known for her satiric song intros as well as her hard-belting vocals. Big boned and six feet tall, she cut a striking figure on stage.

By 1960, Judy had moved to Los Angeles and became a featured performer at the Unicorn, one of the city’s premiere espresso dens. Cracking jokes and wailing ballads, she held her own as the opening act of Lenny Bruce, then in the torment final stages of his comedy career. Judy radiated a beguiling combination of toughness and vulnerability, very different from the more genteel likes of Joan Baez or Judy Collins. She made forays back to San Diego as well, gigging at the Upper Cellar among other venues. For a time, she lived in an apartment in Mission Beach near Belmont Park. She dabbled in local theater, playing a stripper in a production of the musical Gypsy at the Circle Arts Theater. Judy was up for almost anything, whether it advanced her in a clear career direction or not. “I was always game,” she said of those days.

From Bob Stane, owner of the Upper Cellar back in the day; current owner of the Coffee Gallery in Altadena.

When Judy came from Wisconsin to San Diego I believe the first coffeehouse she played was mine, the Upper Cellar. She sang on my stage many times during the same time period as Randy Sparks and Mason Williams. I remember that on many occasions her magnificent voice was so “full” that her blues carried from her throat though my club’s walls to the nearby houses in the neighborhood and through their walls to drown out their televisions. Now, that is a set of pipes! I got lots of juicy complaints and a few threats. She should have been world famous for her renditions of old-time blues and murder ballads, and she had a great sense of humor to go with it. However, Judy Henske, and her ilk, along with the coffeehouses and their overload of talent and creativity, never go the credit they deserved and paid their dues with but meager recognition.

A taste of Judy: Till the Real Thing Comes Along

Under the management wing of Unicorn owner Herb Cohen (future manager of Frank Zappa and Tom Waits), she hit the road and landed a gig in Oklahoma City, where ex-Kingston Trio member Dave Guard recruited her for his new group, the Whisky Hill Singers. “When he saw me play, I had a broken collarbone, so I had this big harness,” she recalled. “It didn’t look bad on me—I had all those buckles hanging down. I wore really tight pants and high heels, and that’s why he chose me over Buffy Sainte-Marie. He was looking at her, but she didn’t have the harness.”

Things happened at a fast clip after that. The Whisky Hill Singers quickly fell apart after making one album, freeing Judy up to sign a solo deal with Elektra Records. Her 1963 debut, Miss Judy Henkse, was a live-in-the-studio affair, blending old-time jazz, traditional folk, and gospel, leavened by plenty of droll stage patter. Judy’s fiery take on “Wade in the Water” is the LP’s best-known tune. A year later came High Flying Bird—its yearning title track was an early folk-rock hybrid that became one of Henske’s signature songs. In between these two releases, Judy established herself as a mainstay of the Greenwich Village folk milieu, performing frequently at the Village Gate with the backing of jazz luminaries like Clark Terry and Herbie Hancock. She appeared on national TV (including The Judy Garland Show), survived starring in an ill-fated musical (Gogo Loves You), earned critical kudos (from the New York Times and Newsweek), and turned down a management offer from Dylan’s main man Albert Grossman.

Stardom should have been assured at this point. Yet Judy Henske never quite crossed the threshold of fame. No one denied she had the raw talent or was lacking in charisma. Somehow, though, she didn’t fit the musical pigeonholes of the moment. Bad management decisions and lack of record company follow-through may have played a role as well. No matter. Judy got married (to Jerry Yester of the Modern Folk Quartet and the Lovin’ Spoonful), had a child, and moved back to Los Angeles. She applied her creativity toward songwriting, developing a literate, dark-tinged lyric touch most fully realized on Farewell Aldebaran, her 1969 collaboration with Yester. Released on Frank Zappa’s Straight label, the album’s tunes ranged from ferocious (“Snowblind”) to eerie (“Lullaby”) and sweepingly psychedelic (the title track). Though its strange delights were largely overlooked at the time, Farewell Aldebaran became something of a cult classic. Next, Judy and Jerry formed Rosebud, a folk-rock quintet that released an eponymous LP in 1971. The band—and their marriage—broke up shortly thereafter.

In 1973, Judy married keyboardist Craig Doerge and decided to spend her time raising her daughter Kate rather than pursue a music career. Though she put aside record-making for PTA and Girl Scouts meetings, she did continue to write songs, collaborating with Craig on tunes covered by Bette Midler, Crosby, Stills & Nash, and others. Once Kate was grown, Judy slowly revived her career. She rekindled her San Diego connection in the 1990s, performing at the Adams Avenue Street Fair and contributing articles to the San Diego Reader. (Her piece about competitive pigeon racing is a hoot!) In 1999, she released Loose in the World, her first album in nearly 30 years. Judy’s keen lyric edge and full-bodied vocals remained vital. She continued to write songs and work on her memoirs into her 80s.

That’s the highs and lows of her career—but there was always more to Judy Henske than bios and discographies could easily tell. When I look back over her life and times, I see a folk artist who was never a folkie, an intellectual disguised as a beatnik blues-belter, an enormously gifted artist who couldn’t take the show biz game seriously. In all her disparate aspects, there was an idiosyncratic kind of unity—Judy wanted to go her own way, wherever it led.

“It doesn’t make any difference to me if I’m not the most famous person on earth or if anybody remembers me in ten years,” she said. “That’s not the point. The point is that, in your life, what you hope to find is some kind of self-realization so that you know who you are—you know who it is you are left with, with those aching bones and the eyes that can’t see. So that you know who that is.”

Maybe Judy wasn’t depressed enough to change the world. She did brighten it, provoke it, make it laugh out loud, and think a little. That can’t help but cheer you up, even in the face of personal sorrow or the universal Apocalypse. Judy lived large and drank deep of life. Her legacy is one of defiant joy, stomped out and flung in the face of the blues.