Featured Stories

John Mayall Gave Me Room to Move

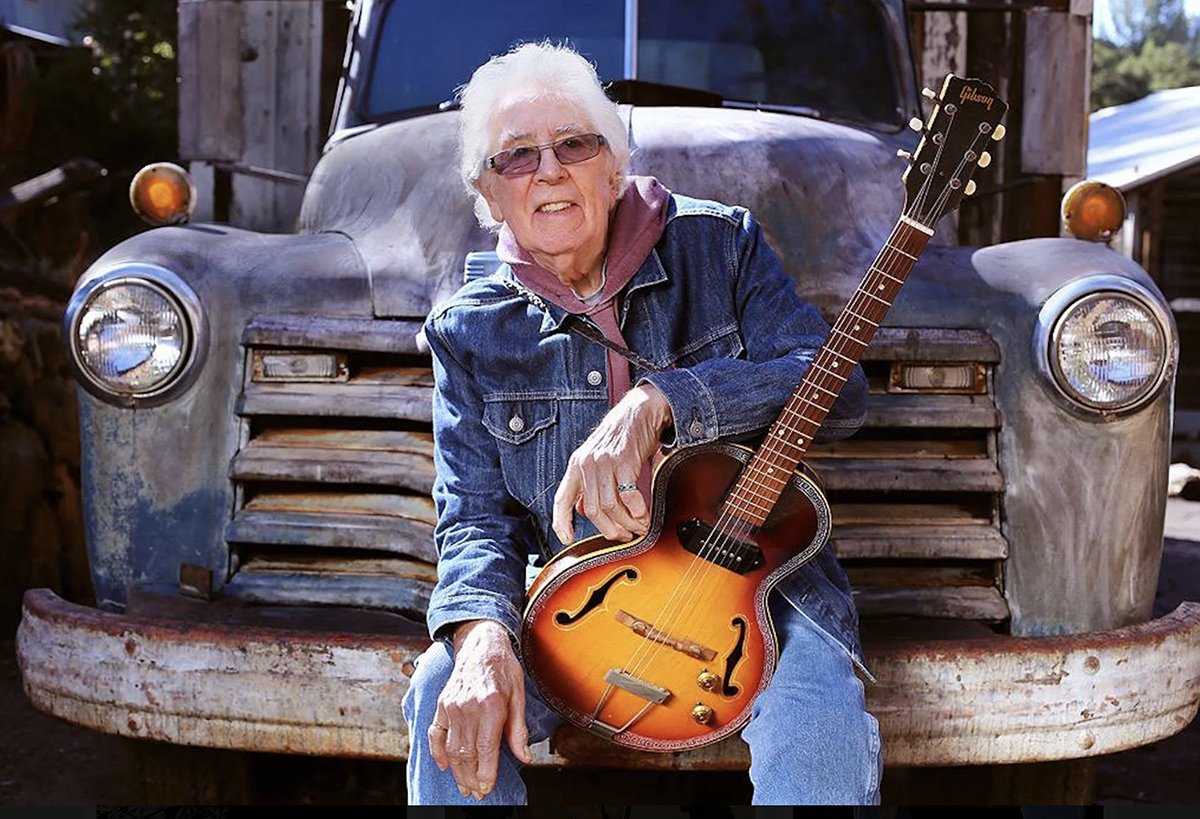

John Mayall at Poway OnStage, 2021. Photo by Dan Chusid.

So, I was scrolling impatiently through the headlines the other morning, sifting through good and bad news, while either laughing or grunting at that morning’s record of events passed by. Then I stopped scrolling. It was a story that featured a flattering photo of veteran British bluesman John Mayall. The only reason why there was a huge photo of Mayall on the news sites gave me a chill, so I read: John Mayall, British blues icon, was dead at 90 years of age. A giant no longer walks the earth.

Born on November 29, 1933, in Macclesfield, Cheshire, England, Mayall’s pioneer work in the earliest days of what became the British blues movement in the sixties marked an historic point in England’s pop music history. He and others, among other pioneers began a revolution of a kind, giving permission to a generation of other musicians to experiment with form, adapt and use musical styles like folk, jazz, blues, classical music and incorporate them into the Big Beat. Mayall formed the influential band John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, which hosted the debut of a brilliant swath of dynamic guitar heroes like Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Mick Taylor, Harvey Mandel, and Coco Montoya.

A constant presence in concert during the ’60s and ’70s, he released 50 or so albums with a constantly rotating, evolving, changing troupe of musicians and players who fit themselves into Mayall’s concepts and made a relaxed yet spikey, tradition-bound but forward-thinking, straight talking but reflective kind of blues expression that soothed, gave hope, and energized the listener. Mayall never achieved the level of success those who followed him did, but it can be argued what we call British rock would be different if he hadn’t been at the beginning. It’s arguable that Mayall was one of the most important music figures of the period.

Mayall’s shadow cast long and large over my young life. He, Butterfield, and Charlie Musselwhite got me hooked enough to learn blues harmonica. Sixty years and hundreds of blown-out harps later, it’s a love affair that continues. Coming upon him and the other white blues revivalists, American and British, changed the direction of my life. John Mayall and his Blues Breakers, on the British side of things, created the whole guitar hero mania that lingers even to this day. An able but unspectacular instrumentalist harmonica, guitar, and keyboardist, he was conversely a brilliant band leader and at times his work gelled to the degree that he was doing something fresh. Mayall and company broke decorum. They sounded alive.

John Mayall and the Blues Breakers, 1960s.

You can hear this on the early Blues Breakers records and later discs that revealed Mayall’s effectively evolving takes on blues music The Turning Point, USA Union. He was a stunning vocalist in the Mose Allison–J.B.Lenoir style—laid back, high-pitched, and no slavish imitation of his heroes. Although not a Butterfield–Musselwhite virtuoso, his harmonica work was appealingly breathy, endearingly folksy, with full chords and splendid slurs and splintery bends that caught the emotion he expressed vocally. What he might have lacked in flash he made up for in texture, rhythm, short runs, and a potent use of pauses between musical phrases that drew you in. There isn’t a modern blues harmonica player alive who hasn’t gone to school on this man’s playing.

Mayall was an able and earnest musician, a chilling and eerie vocalist, a punchy songwriter given to pungent social commentary, but his most demonstrable superpower was his genius as a band leader. His penchant for selecting tasty and distinct blues guitarists and other instrumentalists and allowing those players the full expression of their musical personalities kept the blues grooves fresh and crackling. As with jazz maestros he admired, such as Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers or the ever-morphing Miles Davis, the musicians in his various groups throughout the decades provided Mayall with new frameworks to continually retool his unique style of presenting his music. I give Mayall full credit for putting together crackerjack bands that have, at times, made it possible for him to release first-rate albums. The albums I listen to especially are USA Union, featuring the sadly underrated Harvey Mandel on guitar, Larry Taylor on bass, Sugarcane Harris on violin, and, of course, Turning Point, with the splendid, Paul Desmond-like sax work of Johnny Almond and Jon Mark on acoustic guitar.

Unlike Paul Butterfield, whose early explorations on harmonica extended the expressive range of blues harmonica with fluidity and speed, Mayall’s playing took a different tack. Instead of single-note flurries, he emphasized chords and created a trademarked a “chugga-chugga” kind of rhythm, best noted in his song “Room to Move.” Based on a stirring Latin beat like the classic “Tequila,” the song pops and crackles delightfully as Mayall finds the pocket and stays there. It’s a simple song, with not a lot of technical aspects to it, but what Mayall does is deceptively hard to get. It took me a few years of trying to nail the harmonica parts of the song and to this day the patented Mayall sound eludes me.

Photo by David Gomez.

There are a few of his songs through the years I still refer to when I need a jolt of inspiration, particularly “Television Eye,” featuring Harvey Mandel on guitar from the 1971 Back to the Roots album. A loopy stroll of a shuffle, Mayall’s introduces the theme and mood with some high, lonesome notes on the harp, suggesting a burnished texture while Mandel’s backing throbs and pulses as a well-phased set of chords. Mayall offers a rueful ode to his TV set, a man suddenly aware that all he does is watch the images in dark rooms and finds that he cannot turn away, that he’s addled with a different kind of addiction. Mandel’s solo follows suit and takes full advantage of the room the band leader allowed his soloist. It was here when I decided Mandel was one of the best blues rock players of his generation.

It wasn’t always his harmonica solos or the blustery verve of his guitarists that made the man’s performances memorable. “Broken Wings,” from Mayall’s 1967 album The Blues Alone is a slow and churning song in a minor key, Mayall filling the spaces with the rounded swells of what sounds like a B3 organ, applying thick, resonating chords over his resigned choked-up vocal. It’s a lament for a lost lover who now must deal with the consequences of the decision they’ve made. The keyboard fills the space with a harrowing sound as the progression descends and the volume lowers, fading into a silence as one would imagine a downcast man would lapse into after the last words have been said. I originally heard it in 1967 and it’s been one of doleful melodies that come to mind when old heartaches come back for a visit in the lone, late hours.

That said, it’s a bit of a minor tragedy that we often need to wait for the passing of a musician, a writer, or an artist before most of us take the longer view and realize the depth, gravity, and range of their oeuvres, their lifetime body of work. Admittedly I hadn’t thought about Mayall much in the last ten years, and to be honest I had at times said unfairly critical things about him, But, there was nothing quite like an unexpected obituary to bring history and one’s memory of it into a sharper focus. Which is to say that John Mayall was the necessary man to have around, an artist in the hard reality of the blues, an art of unadorned straight talk about the human condition, and yet one who sought to make the music relevant to the times and temperament he lived in. A paradox, a traditionalist but not a formalist, an innovator but not an avant gardist, a man, a guitar, a harmonica and a voice of undisguised sincerity, singing the blues, carrying the news, inspiring audiences, inspiring others to pick an instrument and create a music of their own.

I bought his albums, I bought a harmonica, and I learned how to play it halfway decently, a voice that gets across what I mean when the words don’t come. So, thank you John Mayall for that gift, and Godspeed.