Cover Story

G Burns Jug Band: Tales of Trains, Tubas, and Washboards

G Burns Jug Band: (front row) Batya MacAdam-Somer, Jonathan Piper, Meghann Welsh, (back row) Clinton Davis, Anders Larsson. Photo by John Hancock.

Busking in downtown San Diego. Photo by John Hancock.

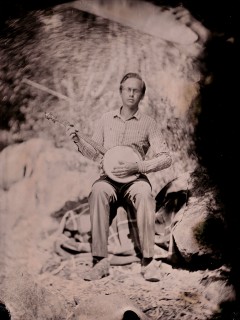

Clinton Davis. Photo by Dave Smith.

Batya MacAdam-Somer. Photo by Dave Smith.

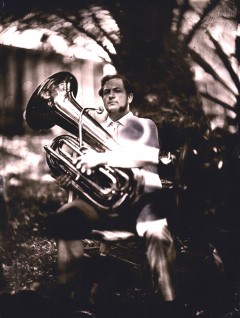

Jonathan Piper. Photo by Dave Smith.

Anders Larsson

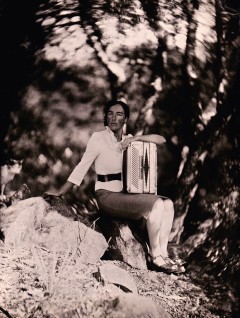

Meghann Welsh. Photo by Dave Smith.

The funny thing about music is that it doesn’t rest so well in history. Because music is a living thing, it challenges us to explore its soundscape, no matter where in history or geography it resides. It is like a comet with a great tail that pulls us into its fiery allure.

Take jug band music as an example.

In the era preceding World War II, especially during the 1920s and ’30s, much of the roots music of the day had been handed down from the years following the Civil War. It came to us through whatever instruments the musicians of the streets and back alleys could conjure and create. If they didn’t have the money to buy guitars, mandolins, or banjos, they made them from cigar boxes, discarded pie plates, gourds, washtubs, and old whisky jugs. The music, which was made predominantly in the Deep South by African-Americans, lay dormant through the middle decades of the 20th Century until it was given a re-birth during the folk boom of the 1950s and ’60s through artists like John Sebastian’s Lovin’ Spoonful, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and the Grateful Dead.

But, for Kentuckian and San Diego resident Clinton Davis, exploring the history of the music of his home town in Louisville was as natural as walking out his front door to climb trees. According Davis, who is enrolled in the ethnomusicology program at San Diego University, exposure to the music of his locale was inspired by his father. “My Dad made sure I grew up hearing good music,” he says. “He would take me to see jug bands that showed the historical connection with where we lived,” Davis recalls. “By the time I got into college, I was studying for a master’s degree in classical piano, but I had a real hunger for pre-war music. I was working at my college radio station,” he says, “and their library was so vast and varied, I learned about all kinds of music. That was when my love for jug band music really began to grow.”

Through his college radio experience Davis found he yearned for something more than mainstream pop sounds. “I find a vitality and joy in the intensity of this music,” he explains. “There’s a depth of feeling that makes playing it very rewarding.”

Today, as he fronts the unique sound of the San Diego-based G Burns Jug Band, he never finds his homegrown music far from his heart. In fact, it’s always just a guitar strum away. And since 2012 he has gathered together a community of musicians to help him realize his dream of playing jug band music. The band has just released a new album, The Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe, with the help of a recent successful Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign.

Along with Davis on vocals, guitar, tenor banjo, and banjolin — a combination of a banjo and a mandolin — the remaining band members, all graduate students in the music department at San Diego University, include Meghann Welsh on accordion, tenor banjo, and vocals; Anders Larsson on percussion, including washboard; Batya MacAdam-Somer on fiddle and vocals; and Jonathan Piper on jug, tuba, and vocals.

While their reputation has grown enough in national old time music and bluegrass festivals to allow them to share the stage with such musical luminaries as Jim Kweskin and Del McCoury, they’re finding enthusiastic appreciation at home. This is evident in their recent nomination for Best Local Recording in the 2015 San Diego Music Awards.

Indeed, it is a well-deserved honor. Their new album authentically captures jug band music in a way that makes it feel immediate and in a uniquely fresh way and current, as though it had been just created today on the front porch of some cabin in the Deep South after an afternoon of emptying a jug of moonshine. Although the band members have a strong musical academic background, it never gets in the way of their performance on this record as they present the feel of an early jug band that has just emerged from a back alley somewhere in Louisville or Memphis. They don’t merely replicate the sound, they have given the music a new life by emulating and embodying the pre-war music of the era. In so doing they have made the music of those early jug bands as relevant today, as an outlet for good times and singing the blues, as they were sung in their heyday.

On familiar songs, “On the Road Again,” and “John Henry” as well obscure nuggets like Ma Rainy’s sex romp “Prove It All Night,” “KC Moan,” and Sarah Martin’s “Jug Band Blues,” the new album, recorded live in the studio at Rarified Recording in North Park, presents the spirit of bittersweet joy and celebration. There is a well-crafted and creative warmth to these sessions that serves as a subtle reminder of the source of this music. It may create a desire in the listener to go back to the original recordings as well as enjoy these present day interpretations. Their sound is infectious and joyfully chaotic as jugs, tubas, and washboards merge with banjos, guitars, and mandolins. The album is distinctly and unmistakably jug band music of the finest kind complete with its own raucous and wooly sensibility.

The history of the music has its genesis in the decades between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War II. While the music was grown in the cotton fields, prison labor camps, minstrel shows, traveling medicine wagons, and by the street songsters and buskers, saloons entertainers and eventually on the vaudeville stage, it was ultimately captured with the advent of recording technology in the early 20th century. Young and old artists alike were brought into the primitive recording studios of the day where they preserved the songs that had been handed down to them for generations. Included in this was jug band music. It also became known as “skiffle” a term that is familiar today when it was used to coin the style of music that became popular in England during the late 1950s. Skiffle even influenced the Beatles.

Clinton Davis’ hometown of Louisville, Kentucky was the first to record jug band music. Although Sara Martin’s 1924 recording of “Jug Band Blues” is often referred to as the first jug band recording, fiddle player; Clifford Hayes’ Old Southern Jug Band recorded songs as early as 1923. Soon, popular recording artists like Jimmie Rodgers included jug band music on their records. The Kentucky style of jug band music is heavily influenced by jazz and blues.

The other landmark region for jug band music was Memphis, Tennessee. The style there was solid country blues. The country style can be heard on the recordings of the Memphis Jug Band, Gus Cannon, Jed Davenport, and Ma Rainy, whose early recordings featured the first appearance of slide guitar via Tampa Red. Ralph Peer, who was responsible for recording the Carter Family, traveled the area with recording equipment, capturing the joyful sounds he heard and sending them out to the world. By 1929, Columbia Records, Okeh Records, and Vocalion Records were releasing jug band music.

As the country moved into the Great Depression of the 1930s, jug band music began to fall silent. After World War II, the musicians began to turn in their unusual instruments to join more traditional blues and jazz bands. It wasn’t long before the unique street music was all but gone in the face of rapid cultural change with the progress of radio and record companies focusing on artists who became stars. When it became labeled as “ethnic” music the result categorized roots music nearly out of existence or at least out of the reach of mainstream (white) audiences. The music was kept a safe distance from popular exposure with their own segregated venues, radio stations, and charts.

However, as a new generation came along in the ’50s, the safe distance created by musical racism began to close in on the bland conformity of the conservative era. As Elvis Presley stepped into Sun Studios in Memphis, rock ‘n’ roll was born, which would set the stage for an even greater explosion, marking the return of jug band music.

Along with rock ‘n’ roll, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s brought in a renewed interest in the music created during the pre-war years. The Folk Music boom of the late ’50s, which grew into an enduring and epic movement of roots music, brought back the jug bands, as the youth of the day went searching record archives for the music of the ’20s and ’30s. It became popular enough to signal a jug band revival that has continued over the last 50 years.

The first jug band recordings of the ’50s folk era was released in 1958 called Skiffle in Stereo by the Orange Blossom Jug Five, which included Dave Van Ronk and Sam Charter in their ranks. In 1963 Gus Cannon’s “Walk Right In” became a #1 hit on mainstream pop charts. Jug band music was back in full force and form with a new generation to champion its roots and bring back to life music born in another century.

No artist did more to spread, modernize and popularize jug band music than Jim Kweskin. His self-named band was founded in Boston in 1963 with friend Geoff Muldaur, who would later bring his wife, Maria, into the fold. The band influenced and inspired young folk singer, John Sebastian, who went on to form the Lovin’ Spoonful, giving a full pop-rock flavor to the music. Most notably, however, was the group of musicians in San Francisco, who upon hearing Kweskin’s music would form their own jug band. Later, they would go electric and call themselves the Grateful Dead.

In the 50 years since the days of Kweskin’s band, jug band music has slowly grown into its own national culture, with festivals and spring and summer competitions. Once considered far outside of the mainstream of national music, today jug band music influences much of what is heard in Americana music through artists like the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Pokey LaFarge. Louisville’s own Juggernaut Jug Band has managed to incorporate pop, jazz, and classical music into the jug band form, covering songs like the Doors classic “People Are Strange,” The Who’s “Pinball Wizard,” and Dylan’s epic “Desolation Row.” It’s all done in expert fun with a trace of early hokum.

G Burns Jug Band represents a new generation of artists devoted to the purity of the sound and form. On The Southern Pacific and the Santa Fe album, the band turns back the musical clock, undoing some of the adaptations done by artists like Juggernaut Jug Band and Jim Kweskin, returning to the blueprint created by the founding artists of jug band music.

At the center of this joyous recreation is the acknowledged front man, Clinton Davis. Along with his own musical heritage growing up in Louisville, he carries a love for the authenticity of pre-war music and its artists. The most revealing comments came during a recent interview when he was asked if the band had considered writing original songs. “Yes, that subject has come up. My feeling is, I don’t want to write anything unless it is as good as these songs we cover.” Of course, that is a daunting challenge, especially with a near endless catalog of songs and styles to work from. For him, this music seems to be almost as sacred as faith and important in a way that suggests the roots of this music runs very deep in his soul.

After graduating with a four-year degree in classical piano, Davis decided to continue his studies at the University of San Diego. Upon arriving, he began recruiting fresh musicians for his vision of an authentic jug band based in Southern California. “I found an openness here to this kind of music that I’m not sure I would find in other places,” he explained. “All of the musicians seemed to come at the right time for the band.” And indeed they did fall into place in a way that allowed for the talented and skilled musicians to learn something entirely new for them.

The members of the band are as interesting as they are diverse. While they are all accomplished musicians in other genres, they had little experience with jug band music prior to joining up with Davis.

Violinist Batya MacAdam-Somer sums it up, “I am a classical violinist by training. I went to Manhattan School of Music for my undergrad and recently earned a DMA at UCSD. I maintain a classical career performing with Quartet Nouveau and other San Diego-based ensembles.” But her cultural family background in Texas allowed MacAdam-Somer a degree of comfort in becoming familiar with jug band music. “I was fortunate to grow up in a rich musical environment that provided me a broad range of influences. I have three siblings who are all musicians — my eldest sister is a violinist and has been fiddling since she was young. We were raised in Houston, a great town for music and certainly a place with ties to folk and country music. So I was definitely drawn to the sounds I heard growing up.

Jonathan Piper has charge of the tuba and the jug. He may be the only jug player in America who holds a Ph.D. His teaching experience includes courses in Western European music from the 1600s. But, his experience with G Burns has been the most unique of his musical life. And while he is a classically educated tubist, the jug became a struggle for him to learn.

“The band started out with me playing the tuba; that’s my instrument. Clint was always pushing me to try out some kind of jug, but nothing ever felt right,” Piper explained. “As frustrating as this was, I felt even worse that we called ourselves a jug band without a dedicated jug player.” But, things would soon change. “Finally, on our first tour, we played a show with the Americans. Their bassist/jug player told me that, in his experience, the trick for brass players coming to jug was that we just didn’t know how hard to blow. He let me borrow his jug for our tour, and I started playing it during busking sessions. That simple advice clicked — the harder I blew, the better it felt and sounded. It can be tricky going between the instruments — jug blowing is way too hard for the tuba, and tuba blowing barely makes any sound on the jug. Now, there are times when I feel more comfortable on the jug. There’s less mechanism between me and the resulting sound, and it almost feels like singing,” Piper said with relief.

For percussionist Anders Larsson, the experience has been equally unique. He is on staff at University of San Diego, however, he met Clinton Davis when the punk-a-billy band Two Wolves, which he drums for, shared the bill with G Burns Jug Band. “When Clint asked me to join I had to give him full disclosure. I told him up front, ‘I don’t play this kind of music.’ My mom was into the folk revival music of the ’50s and ’60s. But, my familiarity with the music was entirely passive. But, the band was looking for a percussionist with a clean musical slate in order to learn the music on its own terms.” Larsson received his master’s degree in jazz studies in New Orleans at Loyola University, the city where much of the jazz orientation of the early jug bands originated. It was there he had experience playing the washboard with Cajun Zydeco bands. “I’ve also learned the spoons and bones, but I have yet to incorporate them into the band in performance,” he said.

One of the critical parts of the story of G Burns Jug Band’s development revolves around the creation of a music scene. When a friend and bandmate of percussionist Larsson gave the band a place to play on a regular basis, the Black Cat Bar became the place to go where they could work out their songs before a live audience without pressure. According to Davis this has been a key part of the band’s history. “The residency at Black Cat Bar has given us somewhere to show up and try out new music,” he said. According to Piper, playing live has been a new experience. “Our shows at the Black Cat have been really important to me, because it has always felt like a safe and supportive space to work on my identity as a jug band musician. Touring feels totally different, since we can’t depend on a rapport with the crowd. But I think we’ve all gotten to a place of confidence and familiarity with what we’re doing that we can count on giving a great performance anywhere we go,” he said.

As a violinist, Batya MacAdam-Somer puts it, “Playing with the band is a blast. I love the sense of abandon I get from the music, sharing that with the rest of the group, and sharing that with the audience as well. Watching people of all ages get up and dance to our music is, for me, sheer joy.”

For Larsson the Black Cat Bar shows have been an important ingredient in the authenticity of the music. “It helps us to put a foot in the real world. Because of the Black Cat Bar and our monthly shows there, the band is not just an academic exercise. You know it’s real when people go there on a Saturday to dance to the music at 12:30 in the morning.”

According to both Davis and Larsson the Black Cat Bar has an old school feel to it without being contrived. It has a vintage feel that gives the band’s music the kind of atmosphere it needs. For G Burns Jug Band, this has been critical to the group’s success.

As the band carries on with the long tradition of pre-war music, there is much to discover, uncover, and recover from the historical archives left behind by the musicians of the past. But, this band of musicians is now in the midst of resurrecting something that is vitally important for us. It is a treasure that cannot be contained merely in history, but must also be expressed by the best and the brightest of us. G Burns Jug Band has proven this to be a reality.