Cover Story

From Across the Pond: Dave Humphries Brings a Bit o’ British to San Diego

The Dave Humphries Band at Rebecca’s: Mike Alvarez, Humphries, Wolfgang Grasekamp. Photo by Jerry Hutchins.

The world, and its inhabitants, is a swirling dialectic of complementary opposites; nationalism distinct from globalism–the sovereign individual in grand contrast to the sprawling collective. It’s a cosmic push me-pull you choreography of capitalism, socialism, communism, and humanism–all trying to tap you on the shoulder, asking if they can cut in and assume the lead, even if they’re a tragically hopeless dancer. We live in a world of closed systems yearning to breathe and break free from dogmatic constraints, aspiring toward the liberty to evolve into a divine representative of the human race without being encumbered by the fascistic governance of the state.

Theoretically, that’s a thin slice of the perspective offered by the official his-story of how the United States of America came to separate itself from the tyranny of Mother England. But Great Britain and the U. S. are rather like Siamese twins: two heads upon the same cultural body that seemingly wish for distinct identities, but in reality moves about with the same arms, legs, torso, and wallet. But if opposites do indeed attract, then perhaps Oscar Wilde said it best when he observed that the Americans and the British have everything in common except the language. A fantastic example of what Wilde was on about is in the interpretation of how the Yanks and Brits have chosen to play rock ‘n’ roll music over the past 70 years. Without Elvis Presley there would be no Cliff Richard. But even the “King” of Tupelo owes a debt to the many artistic visionaries from whom he aped and who came before him. Rock ‘n’ roll remains a moveable feast, a cultural roux where anyone can add their specialty spices to the existing stock and potentially come up with something vital, exciting, and distinctive if their culinary skills are up to the task of transcending the status quo.

It’s true–anyone can connect themselves through the parlor amusement of playing the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” if you put your noggin to the task and connect the dots. But to be one or two degrees removed from the rock royalty of the Beatles is a far more impressive association, and Dave Humphries’ CV glitters with multiple collaborations within the circle of the Fab Four. So much has been made over the years of Humphries’ allegiance and fealty to Liverpool’s finest that you might think he’s some kind of Anglicized one-trick pony. But the last couple of CDs that Humphries has released under the moniker of The Hollywood Project have proven that his musical palate far extends beyond the Lennon/McCartney matrix that he has long been affiliated with. Mellow yet jaunty, with a dash of melancholy at times that leaves an imprint of introspection–there’s a distinct bounce to Humphries’ music, a bit of the old music hall vibe. Because, as the old saw goes, you can take the man out of England, but you can’t take the English out of the man. Even after 22 years as a San Diegan, the native lilt in Humphries’ character and speech hasn’t faded in the slightest. And from my observation point, that is a rather charming thing to behold.

Born on April 18 in Durham City, England, Humphries came of age at the perfect time to have a front-row seat when the bleak austerities of post-war Britain gave way to the kaleidoscopic technicolor of the swinging sixties. “In the early ’60s you didn’t have much music on the BBC, especially rock ‘n’ roll,” says Humphries. “I started getting into music, I suppose, because my dad was mad on Bing Crosby. We had a gramophone, and I liked “I’ve Got My Captain Working For Me Now” as well as his ballads. The first record I bought was in ’62: ‘Return to Sender’ by Elvis.”

Within a few years Humphries started picking out chords on his first guitar. “My dad got a guitar,” he says. “He wanted to sing old cowboy songs like ‘Home on the Range.’ And there was a guy where we lived behind our back garden who had a guitar, and he said he would teach me. But all I learned from him was ‘G’ and ‘C.’

“I used to pretend I was playing the Shadows guitar–Hank Marvin, Bruce Welsh–those two were from the northeast, so they’re a bit like local heroes. And then, of course, the Beatles happened, and at first I didn’t care for them, because they were never off the radio. But then my younger sister Lynda arrived with the Twist and Shout EP [which also included “A Taste of Honey,” “Do You Want to Know a Secret?,” and “There’s a Place”]. She started playing that, and I went ‘Wow! What is this?’ And she says, ‘Why, it’s the Beatles.’ And I’ve been crazy on them ever since. And, as far as the guitar goes, I got a cheap one in ’66–you could get a matchbox between the action of the strings and the fret. You hear stories about people playing ’til their fingers bleed? And so they did.

“My first public appearance was at a little school concert when I was about 15. Me and two other guys were up there and we did three or four songs. I remember doing ‘Can’t Buy Me Love,’ ‘Morningtown Ride’ by the Seekers (because the music teacher wanted us to do that one), and then we did one that we had written ourselves called ‘The Girl from Tomorrow.’ ‘The girl from tomorrow came to my house today, she then found out that I had gone away,’” he recalls with a chuckle.

Humphries went through the typical trial and error of figuring out where he fit into the pre-existing social strata of British society, which is largely determined by how well you do in school. When he didn’t pass his 11-plus exams, he was encouraged to learn a viable trade.

“That’s the cruel thing they used do to kids at the age of 11. If you don’t pass your 11-plus exams they send you to a secondary modern school rather than a grammar school. If you weren’t up to speed, or you were a slower learner, or you were like me and you freak out when you get exams and you fail, that can affect the rest of your life. I don’t regret any of it. But that class thing was still present: ‘Oh, you’re secondary modern,’ like a second-class citizen. They’re always hammering into you ‘Get a trade, get a trade.’ I ended up being a clerical officer for the National Health for a long time until I was trained in the use of computers. I was involved with IT networks and troubleshooting.”

But all the while Humphries was in the corporate world he still pursued his musical aspirations, continually improving his technique as a guitarist. “We had a little band in ’67, ’68. We were just doing church halls, stuff like that. You would go out to see bands and stand in front and watch the guitar player and go, ‘Aaah! What was that chord?’ And you’d write down a little diagram, and you’d have E7 or B7 or a different way of playing D7. And then you’d go home and try to write something around that.

“I started a new job working for the government and one of the guys that I met was a lead guitarist and he said we should do something. That group was called Biffo. We used the shape of a boxing glove as our logo. We were mostly performing in working men’s clubs. But we did audition for a television show and then we got a big one at Dunelm College with 3,000 people in the audience. It was the same stage where I saw the Moody Blues perform On the Threshold of a Dream in its entirety.

“We had a couple of drummers in Biffo that would just up and disappear. It was a bit like that movie This is Spinal Tap. This one drummer, who was a bugger for the bottle, he went for a roll around the kit and fell off the stool! With a pair of feet sticking up. And then later at the same gig we’re playing away, and all of a sudden I couldn’t hear any bass guitar. And the bass player was out in the audience selling bingo tickets. And another time somebody was dancing with his girlfriend. He was off the stage and we could hear some commotion in the middle of a song, and he had this guy up against the wall with the neck of his guitar under the guy’s chin. ‘You leave my girlfriend alone.’ So we changed the lineup after that. We got a better drummer and a new bass player.”

****************

Before Biffo, Humphries had a group called The Idea, and like any other band on the make they had dreams of breaking through to a larger audience. Particularly after they spotted an advert in the New Musical Express and Melody Maker magazines with an improbable photograph of a one-man band singing into a microphone, bass drum strapped to his back, a guitar on his lap, with a record player, reel-to-reel tapes, and a trumpet at his feet. The ad copy makes the following pitch: “This man has talent…One day he sang his songs to a tape recorder (borrowed from the man next door). In his neatest handwriting he wrote an explanatory note (giving his name and address) and, remembering to enclose a picture of himself, sent the tape, letter, and photograph to Apple Music 94 Baker Street, London, W.1. If you were thinking of doing the same thing yourself–do it now! This man now owns a Bentley!”

“So, we decided to go down to London, three of us from The Idea,” says Humphries. “It’s an overnight bus trip out of Sunderland. We had recorded these things in a church hall on a Grundig tape recorder, and we’d seen the advert. We didn’t have our guitars, just a little reel-to-reel tape. And we got to Baker Street and there it was: the windows whitewashed with ‘Revolution’ on one side and ‘Hey Jude’ on the other. But it was closed. It was early September ’68, the single had only been out a week and I had already bought ‘Hey Jude.’ So we get on the tube and go to St. John’s Wood looking for Paul McCartney’s house. We get on the street that Paul lived and he has these big double gates with a bell and barbed wire on the top. We see this women coming down the street and she says, ‘I’m Rose, Paul’s housekeeper,’ shaking our hands and asking, ‘Where have you come from?’ ‘All the way from Durham.’ ‘Well, what do you want?’ ‘Why, we’ve brought this thing for Paul.’ ‘Well, let me take it in and you come back tomorrow and I’ll be able to tell you what he said.’

“So we spent the night and she comes out the next day and says, ‘Will you take it around to 3 Savile Row?’ ‘Paul said that?’ So we danced away down the tube excitedly and found 3 Savile Row. We went down those basement stairs that was eventually the studio that you see in the film of Let It Be. There was Apple green carpet in every room with white walls and grey furniture and in the main reception area they had big posters up of Jackie Lomax and Mary Hopkin and the Fabs.

“But there was no one there in the office except some workmen. After walking around the offices I just stuck the tape under an ashtray on the receptionist’s desk with a little note. And then we came home.

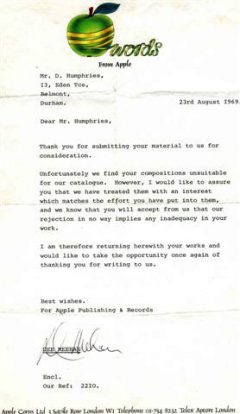

“And then I got a letter a week later from Peter Asher, saying thank you but it’s not what we’re looking for. And years later, Peter Asher is at the Coach House and when the show had finished I had a copy of the letter and I said, ‘Can you explain yourself a bit here?’ And after reading the letter he says, ‘Apparently, I didn’t like it.’ We submitted a second tape to Apple but that one received the same response. I’ve still got the letters with ‘Words from Apple’ on top of the stationery.

“So that story has followed me around over the years. And there’s lots of people who think ‘Oh, Dave Humphries, he’s just Beatles.’ But I only do a couple of Beatles songs normally–unless I’m doing a Beatlefair. I do like to perform ‘Tell Me If You Can,’ a song that Tony Sheridan wrote with Paul McCartney back in the Hamburg days, because it’s never been recorded or released.”

****************

Much as he’d like to downplay it, the Beatles inadvertently led to Humphries moving to San Diego after meeting his future wife to be, artist Robbie Taylor, at a Beatles convention in Liverpool in 1991. Several years later, in 1995, Humphries took a vacation with his cousin Colin and wife, Barbara, to visit California, and the previously platonic dialog with Taylor blossomed into a full-on romance. The two bopped back and forth from the U.S. to the U.K. before getting married at midnight on July 27, 1996 in Las Vegas, after enjoying a Jerry Lee Lewis concert. In one fell swoop he not only gained a wife but a stepson and daughter, and now has four grandchildren that he shares with Taylor. Humphries explains, “John’s a professor of creative writing in Long Beach, and Nikki is a teacher up in Oregon. They are great kids, top class. Once they got to know me they were so supportive, and they love me like a dad. And my mum died five years ago, but my dad’s still in Durham and the kids have all been over there and met me parents.

“When I first came to San Diego Robbie had to educate me a bit because there are different rules about hanging out with people here–you don’t just meet them in the pub like you do in England. You walk around and do other things rather than just be barflies,” he says with a laugh.

“I was playing a bunch of old rock ‘n’ roll tunes when I was still in Britain–‘Sea Cruise,’ Buddy Holly, and things with a saxophone. But when I came over with Robbie I didn’t do much for a while. I had written a couple of tunes, but I didn’t do anything with them until Wolfgang arrived.”

It was in 1999 that Humphries met keyboardist and producer Wolfgang Grasekamp. Grasekamp is a native of Germany who had been performing with the legendary Tony Sheridan, who famously used the Beatles as his backing group when Sheridan recorded a handful of songs in Hamburg in June of 1961. (For a more detailed profile on Tony Sheridan see the October 2012 edition of the San Diego Troubadour.)

“Carmen Salmon, one of the originators of the San Diego Beatles Fair back in the ’80s, said that Tony was coming to play and that he needed a place to stay. So Robbie and I volunteered to put him up. One day when I came home from work there’s Tony Sheridan sitting in my chair drinking my beer. Wolfgang ended up getting married to his [late] wife, Janie Duggan, here in La Mesa, and Tony was back in Hamburg. After the Beatles Fair he rang me up and said we should do something together. And that’s how that started.”

The first project that Humphries and Grasekamp collaborated on was 2000’s Shooting the Breeze. A couple of years later they followed up with the CD Years Away. They have continued collaborating to this day (earning a San Diego Music Award nomination along the way), gaining accolades for 2008’s and so it goes… and 2010’s Hocus Pocus on Joker Lane. The compendium Retro was released in 2014.

But Humphries’ songwriting took an unexpected left turn in 2015 when lyricist and poet Stephen Kalinich asked him if they could collaborate on some songs together, with Kalinich sending his lyrics to Humphries and Humphries crafting the melodies and setting them to music. Kalinich achieved some notoriety in the ’60s and ’70s by writing a handful of songs with the late, great Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, producing the sublime beauty of such tracks as “All I Want to Do,” “Be Still,” and “Little Bird.”

Humphries says, “I met Stevie through a guy called Ken Michaels, who is a DJ out of Connecticut that produces the Every Little Thing syndicated radio show. He came out here to California to meet Stephen Kalinich, whom he had met somehow. I’d given Ken a copy of Retro and we’re driving all over Beverly Hills with Steve in the car. And the chat is going on and then Steve asks who is on the CD player? ‘That’s Dave.’ ‘Dave who?’ ‘Dave sitting in the back.’ ‘Oh! I’ve asked you before: will you do some stuff with me? So I said just send one and we’ll see how it goes, and that was ‘No One Like U’ and it worked out nice so then he sent another couple of lyrics. And that became No One Like U. ”

Produced and arranged by the illustrious Grasekamp, the trio dubbed themselves The Hollywood Project. The collaboration went so well on the first ten songs that they wrote ten more for 2017’s Olympic Boulevard. The result is Humphries’ finest collection to date, maintaining a vibe of melodic introspection that is more compelling with each successive spin.

Since retiring from the workaday world of nine to five, Humphries has maintained a busy schedule performing at such venues as (the currently defunct) Rebecca’s Coffeehouse, Lestat’s, and Java Joe’s. A couple of recent showcase gigs at the Coffee Gallery in Altadena went surprisingly well. “The audiences are so responsive and quiet and appreciate what you do,” says Humphries. “They’re not yapping on and looking at their phones. 25 bucks at the door and its packed–it was wonderful.”

After touching down in San Diego in 1996, Humphries has played at nearly every San Diego Beatles Fair, and this month–on Saturday, March 31–he will be turning in what is bound to be another fine performance with his regular backing ensemble Street Heart, featuring Wolfgang Grasekamp on keyboards, Tom Quinn on lead guitar, Gus Beudoin on bass, Todd Sander on drums, and the ubiquitous Mike Alvarez on cello. Additionally, Harry Nilsson’s son Zak is sitting in on drums for a couple of songs. Zak Nilsson and his brother Kiefo have been diligently keeping the flame alive for their father’s music, spearheading a campaign to get Nilsson into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (“Get Harry in the Hall”). (For a more detailed look at Harry Nilsson’s career and his association with the Beatles, check out the May 2015 edition of the San Diego Troubadour.)

Since 2012, the San Diego Beatles Fair, which originated at the Scottish Rite Event Center, has been revamped and overhauled by a team of volunteers headed up by Salmon, Taylor, and Alma Rodriguez, the owner and host of Queen Bee’s Art & Cultural Center, where the San Diego Beatles Fair has resided for the last six years. “There wouldn’t have been a San Diego Beatles Fair if we hadn’t brought Tony over in 2012,” says Humphries. “That was the year he took ill and he ended up doing an abbreviated performance.” When Sheridan returned to Hamburg, Germany, he recovered from his bout with the flu, but ended up passing away on February 16, 2013, after undergoing heart surgery. “I loved Tony so much. When Robbie and I visited him and his wife, Anna, in Hamburg he took us on a tour of the Reeperbahn, pointing out all the places of historical importance during the Beatles’ time there. ‘There’s where Paul and Pete [Best] were in jail, and there’s the Indian that we always used to eat. And there’s the Indra, and the cinema where they slept when they worked at the Kaiserkeller; this is the church and John was on that balcony [urinating] when the nuns went past. And then we went into Gretel & Alfons, the bar across the street where all the bands used to go for a drink in between sets from the Kaiserkeller. Tony says to us, ‘You wanna go to the bog yet?’ ‘Why?’ ‘So you can go and piss in the same pot Lennon did.’ So I did. And then back to Tony’s place, stayed the night, and we wake up and he’s making us breakfast: bacon and eggs and fried tomatoes–great.”

It was through Humphries and Taylor that Joey Molland from Badfinger came down to perform with Humphries’ band at the 2014 San Diego Beatles Fair. Other distinguished guests have included Denny Laine, Louise Harrison, Billy J. Kramer, and Liberty DeVitto. This year’s special guest will be the original Beatles’ drummer Pete Best, who will perform on Friday, March 30, before the festival swings into high gear the following day.

****************

Besides sharing a common love for art, music, and the Beatles, both Humphries and Taylor are compassionate about animal rights, supporting the Humane Society, Second Chance Dog Rescue, and Friends of Cats. In 2007, they also produced a handful of shows to raise money and awareness for autism. In addition to doing charity work and giving back through various organizations, Humphries says that next to music and family his other passion remains soccer. “I love me Manchester United. And I do like to go down to Shakespeare’s Pub and have a tipple or two.”

Dave Humphries is the true British Invasion, who pours his heart and soul into everything he does. The San Diego music community is lucky to have him, and I for one can’t wait to hear what the sly devil has up his sleeve for his next project. Without a doubt it is bound to make you think, and have you tapping your toes and singing along. And isn’t that what the best music inspires?