Raider of the Lost Arts

Diva

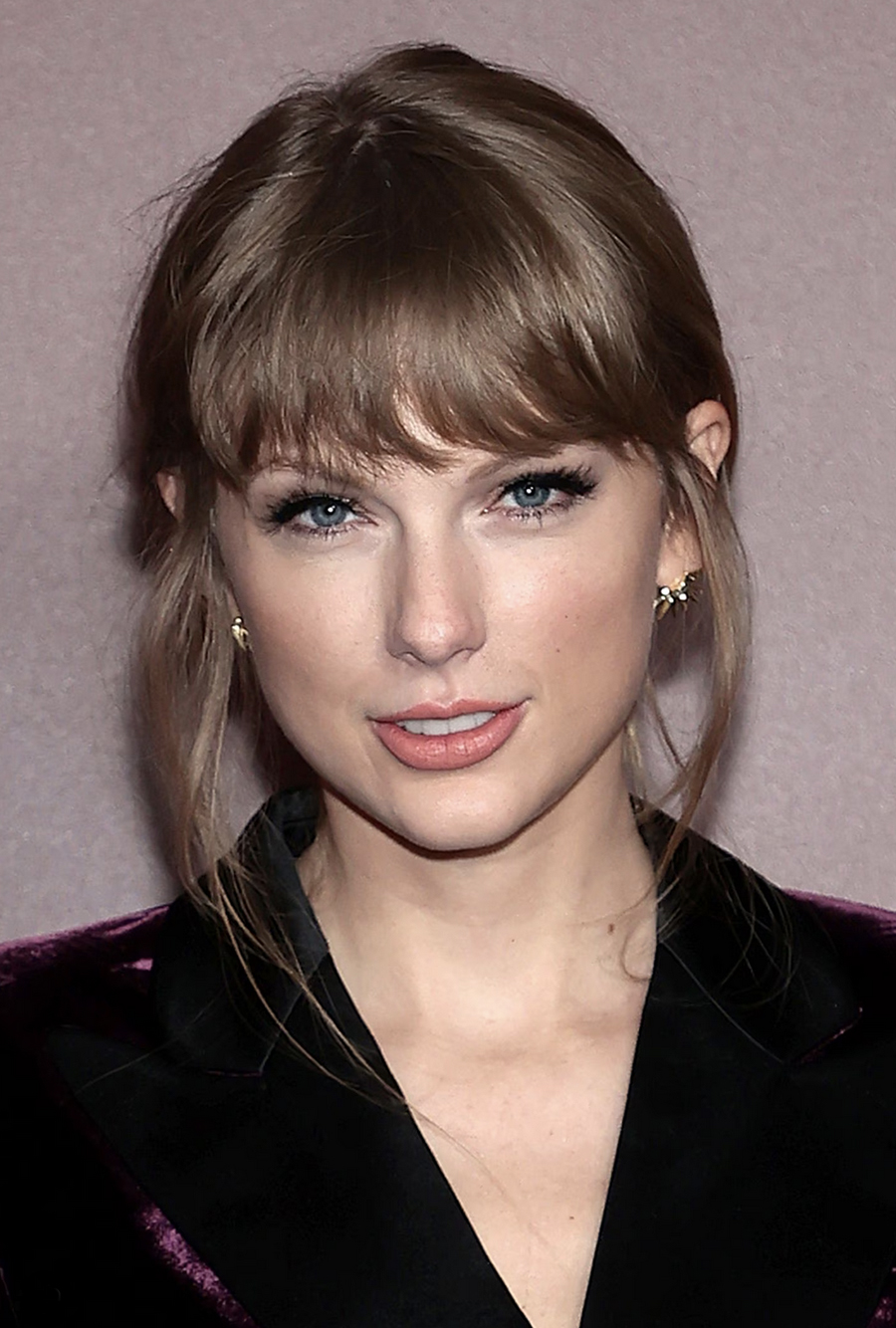

Taylor Swift

There’s something off about Taylor Swift…isn’t there?

Despite possessing the statuesque––and ergo the most expedient––corporeal proportions to satisfy the modern music industry’s criteria for success, and yet after also having brazenly decried various echelons of injustice (including the music industry itself), Swift seems too mousey, subdued, and insubstantial to be a famous pop star, almost like a pre-pig-blood-doused Carrie as the unlikely prom queen in the eponymous 1976 movie.

Swift is the paragon of the modern female pop singer, which appears to be nothing if not a premeditated hybrid of supermodel and stripper; the stage moves are mostly perfunctory catwalk struts, sassy gesticulations, and akimbo poses alongside salacious hip gyrations that leave next to nothing to the imagination but somehow manage to sneak in under the hair-trigger censors’ radar. The wardrobe is sequined bathing suit onesies or variations thereof, and Swift wears them like a tween playing dress-up, trying on the requisite, de rigueur role of empowered provocatrix but unwilling or unable to embrace or embody it beyond rote imitation, just a brief stop on the compulsory costume-change train route of lingering innocence. Her voice is nice, but in an innocuous, ineffectual way; it could be any generic white girl soprano onstage or on the recordings, and by no means does it scream “powerhouse virtuoso.” No one would blame her if she claimed to suffer from impostor syndrome, though the fiercely protective, innumerable throng of “Swifties” would be quick to reassure her to the contrary.

Swift is no prime-era Madonna; for better or worse, she is still very much the unassuming naïf who came up in Nashville at too young an age, having remained herself instead of submitting to the alchemical transformation that most famous people have to undergo and with which they usually have difficulties reconciling, like a child actor, or anyone else who becomes prematurely renowned. Or perhaps, and in line with the metamorphosis into the exaggerated avatar of one’s true nature that fame represents, Swift has undergone the crossover only to emerge the same as before––still vexingly stunted. A few months shy of 34—and just like early-period Beatles—Swift is still writing almost solely about romantic relationships with the puerile giddiness and indignation that has become her stock in trade, the main difference being that she tends to focus all but exclusively on the period immediately after they end, with many of the lyrics reading as self-exculpating kiss-offs to the latest celebrity boy toy.

Sure, she can turn a clever phrase, she’s got earworm hooks (just seeing the title, “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” brings it all rushing back like a resurgent fit of malaria), and is middling to fair with a metaphor, but most of her lyrics read like entries from a love-obsessed teen’s journal, which is why girls across so many age groups have cottoned to her; they are either enviously overeager to reach the age of consent so they can finally understand and relate with the hypnotizing, hyper-romantic words along to which they so zealously sing, or are in the thick of it themselves, or are the parents of these two groups, vicarious veterans of the love wars Swift describes, longing for the taste of erstwhile thrills from the hunkered-down bunker of middle age. And yet a rational listener is hard-pressed to accept that Swift has actually undergone or otherwise earned any of the angst-generating experiences of which she writes, especially the pre-emptively self-castigating, incongruous bravado of a newer song like “Anti-Hero,” which happens to be uncharacteristically introspective:

I have this thing where I get older but just never wiser

Midnights become my afternoons

When my depression works the graveyard shift

All of the people I’ve ghosted stand there in the room

I should not be left to my own devices

They come with prices and vices

I end up in crisis (tale as old as time)

I wake up screaming from dreaming

One day I’ll watch as you’re leaving

‘Cause you got tired of my scheming

For the last time

It’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me

At tea time, everybody agrees

I’ll stare directly at the sun but never in the mirror

It must be exhausting always rooting for the anti-hero

Sometimes I feel like everybody is a sexy baby

And I’m a monster on the hill

Too big to hang out, slowly lurching toward your favorite city

Pierced through the heart, but never killed

Did you hear my covert narcissism I disguise as altruism

Like some kind of congressman? (Tale as old as time)

I have this dream my daughter-in-law kills me for the money

She thinks I left them in the will

The family gathers ‘round and reads it and then someone screams out

“She’s laughing up at us from hell”

She’s no Fiona Apple, Alanis Morissette, or Sinéad O’Connor (RIP), let alone Joni Mitchell or Carole King, who were all more believable as well as eloquent. And yet the gargantuan “Eras” tour crowds have been eating it up as if Swift is their own personal Jesus (anti-heroes don’t do massive stadium tours, honey)…

All of this is why Kanye West saw fit––and was able––to usurp Swift’s crowning moment at the 2009 MTV VMAs on Beyoncé’s behalf. More than just an embarrassing faux pas for both parties, it was a clash of polar opposites, with the unjustifiably swaggering (and in that particular moment ironically non-self-aggrandizing) West in one corner and the waifish Swift cowering like a head-lit deer in the other.

In other words, she may be in the midst of the highest grossing and most grueling tour of all time (with the show clocking in at a Springsteen-esque three hours, one has to at least give her three snaps up for her insane work ethic), and she may have sold millions of albums and billions of streams, but Taylor Swift is no diva.

*******************

It ain’t over till the fat lady sings. —(attr.) Ralph Carpenter

Diva translates to “goddess” from the Latin and often refers to “a celebrated woman of outstanding talent in the world of opera, theater, cinema, fashion, and popular music,” all according to Wikipedia. The definition also alludes to the coin’s dark side in its mentioning of the words “temperamental” and “demanding,” (“troubled” could also easily be appended). The masculine divo saw some use in the early days, way back in the 19th century, but it never quite caught on; something about the feminine embodiment of objective beauty and subjective emotion––not to mention millennia of male oppression––has staked an exclusive claim on this franchise for the fairer sex (and divo reads too much like the quirky new wave band from Akron).

Historically, and in line with the quote and definition above, a stereotypical diva was the often corpulent, always a powerful female soprano or alto in the operas of yesteryear, for whom the composer would write arias to specifically showcase her prodigious talent and grand presence.

Though opera was considered the pop music of its day, the diva concept crossed over to the new pop song genre in the mid 20th century, granting at least some of its privilege and onus to the likes of torch-song crooners like Billie Holiday and Etta James, with Judy Garland, Édith Piaf, Julie London, and others doing their best to keep up. In the ’60s it was women like Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, Cass Elliott, Barbara Streisand, and Dusty Springfield as the latest flag bearers. The standard got passed to Chaka Khan, Patti LaBelle, Cher, Stevie Nicks, Ann Wilson, Kate Bush, and more in the ’70s.

An interesting phenomenon came to widespread prominence in the ’80s and ’90s that would irrevocably change the paradigm:

The emergence of Supermodels.

A fair amount of this revolution could be attributed to the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue’s rise in popularity, and the concomitant increase in visibility of the fashion industry in general, abetted by the likes of Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington and Brinkley, Heidi Klum, Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks, lingerie monger Victoria’s Secret, and a host of others. This sex-sells aspect had been coöpted by pop music early on, but was now eagerly re-embraced in an attempt to guarantee higher record sales for the always-looking-for-a-game-rigging-angle major labels, especially with the advent of MTV in 1981 and the progressively visual way in which we began to consume music.

Not that the preceding ladies weren’t beautiful in their own right, but suddenly women in pop began to look more like runway models than traditional divas. Gone were the gowns and modest dresses of erstwhile eras, replaced by tight-fitting skirts, lycra leggings, and even underwear and lingerie.

Luckily, some of the new breed still possessed the requisite talent and substance. In the ’80s, an artist arose who seemed to embody both the old and new criteria to a tee:

Whitney Houston.

Whitney Houston

Utterly gorgeous and possessed of an astonishingly powerful vocal gift, Houston was the apex diva, the pinnacle of everything we’ve hereafter come to expect from our female pop stars. Highly visible in cinema and fashion as well as music, she was glamorous and down to earth, magnanimous despite exhibiting the all-too-real foibles that would ultimately undo her but which also made her insanely relatable. Even when she fell from grace, anesthetizing herself with well-beneath-her-stature vices as she circled the drain in her toxic marriage to Bobby Brown, we rooted for her comeback, not her downfall like we normally tend to. Her 2012 demise still feels like a tragedy of Princess Diana proportions.

Mariah Carey took up the torch in the early ’90s, carrying it into hip hop’s ascendancy with one of the most expansive vocal ranges and timbres to ever grace a microphone. Capable of supersonic “bell tones” reminiscent of Minnie Ripperton on “Loving You” (though Mariah definitely took it way past that preëstablished end zone), Carey may have been one of if not the first of many diva contenders to collaborate with the popular rappers of the day, using the stark contrast bestowed by the juxtaposition with ruffian spitters like Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Jay-Z to enhance her regal image and garner some street cred to boot. That same intuitive zeitgeist attunement also led her to record an as of yet unreleased, adventurously off-brand grunge album that even now begs to be heard.

Carey’s struggle to break free of her Sony label head and then husband Tommy Mottola was a continuation of the precedent Tina Turner had set to emancipate and empower herself independently of the abusive patriarchy that many divas before and since have also pursued. In fact, overcoming personal and professional hardship––on top of battling persisting misogyny and record industry exploitation––could be part of the diva’s job description.

Along these lines, another section of the CV could pertain to race, as the most prominent of the gifted forerunners mentioned herein are women of color. Having already hit their heads repeatedly against not only the glass ceiling but also the lingering vestiges of the Jim Crow wall, there is something about this subset of women having to overcome higher obstacles and endure wider-amplitude hardships that has exacerbated both the strengths and weaknesses of these particular entrants in this tragic pageant, and has given them grist far and beyond straightforward, saccharine declarations of love and heartbreak for their songwriting mills.

In the late ’90s, a young woman would come along and move things undeniably forward, picking up where Mariah Carey left off as far as being one of the first artists to fully integrate the rhythmic flow––and some of the lyrical tropes, especially of the “diss track” variety––of hip hop into vocal pop music. First as leader of the very much of-the-era girl group Destiny’s Child, then subsequently as a no-surprise-there solo artist, Beyoncé Knowles has become an unassailably monolithic institution in her own right, duly earning the moniker “Queen Bey” with her monster hooks, self-penned lyrics for classic songs, and bedazzling live show dynamism (including her Tina-Turner-on-molly choreography), all performed with a classic entertainer’s panache. Throw in a little creativity-enhancing real-life drama with husband and aforementioned rapper Jay-Z, hold the lid down and press blend, and you’ve got the makings of a diva smoothie.

Thanks to Beyoncé and so many other hopefuls of the ’90s, ’00s, and ’10s (including TLC, En Vogue, Christina Aguilera, Kelly Clarkson, Amy Winehouse, Pink, Adele, Florence Welch, Lady Gaga, etc., et al.), the current pop charts are unequivocally and deservedly ruled by female artists. This is a good thing, some long overdue recognition and remuneration no matter the judgments one might make regarding what they had to do––and the validity of the resulting music––to get there.

*******************

Beyoncé mostly stays out of sight between tours these days, preoccupied with raising three kids and keeping her profligate husband in check, and with nothing left to prove artistically or otherwise. The resulting air of mystery is a heady tonic in our pervasive overexposure culture, but one almost wishes she were just a bit more prolific and visible, considering her genuinely empowering influence on her legion of followers.

Taylor Swift continues to be a summer blockbuster instead of an Oscar contender, the perfect projection target for today’s vast crowds of escape-seeking denizens desiring shallow thrills and externally directed idolatry of a morally nonthreatening but visually enticing golden calf as a distraction from the malaise accrual of ongoing crises. Her approach to self-emancipation from the industry that made her rich and that now, unsurprisingly, holds all of that insanely profitable past work hostage––the rerecording and rereleasing of those previous albums to gain rightful control of her own work––is laudable in its ambitious novelty, but also a dumbfounding shame, as Swift is not only frittering away excessive time, energy, and money, but also passing up a massive gift-horse opportunity to reinvent herself as a full-fledged adult artist who has—both literally and figuratively—finally let go of her sophomoric past. Though “Anti-Hero” represents a promising but hardly surefire harbinger of what might come after the big redo, naysayer pariahs await her “Paperback Writer”––the first song a Beatle wrote that wasn’t about love, or relationships’ beginnings or endings, or themselves, and that required some genuine imagination on Paul’s part––with pessimistic expectations.

What’s needed in today’s society is more along the lines of the all too recently deceased Sinéad O’Connor and her confrontational brand of shout pop (or even “Nothing Compares to You”-type R&B laments, which are more believably heartrending than Swift can seem to muster), but O’Connor appeared to be too much for most punters to take, even well past her scandalous heyday (though the entirety of her life seemed rife with controversy…). People don’t seem to fancy the stark, cutting, unadorned truth very much lately, if they ever did, as it attacks their sedated status quo.

What we need are the true divas, the ones who are genuinely empowering and enriching for audiences as opposed to simply a distracting siphon icon. Future aspirants need to be educated as well as groomed, and should perhaps begin their ascent later in youth so they can stockpile more and varied real life experiences upon which they can draw once fame has ruthlessly transmogrified them into ubiquitous, out of touch pin-ups.

The world urgently needs new heroes of substance, a scarce commodity in this house-of-cards reality, but now doesn’t seem to be the right time. And besides––heroes begin their unsought tenures as part of the vast, anonymous underground, not the reachable-by-one-percent firmament.