Featured Stories

California Young Guns: The Birth of Country Rock, Part 1

This is part one of a two-part series, chronicling the birth and legacy of California country rock. Because the roots of this genre of country music go so deep, and its influence is so far reaching, it’s difficult in a two-part series to cover every detail. Also, the important influences, high-water marks, artists, and current progeny of the form are based on the writer’s own perspective. It is hoped that this series will give country rock some historical perspective and spur the uninitiated to pursue their own musical investigation of this bastard child of country music.

PART ONE

Throughout the 1960s and into the mid-1970s, California, in particular the southern coastal region, became the proving ground for a new, edgy, provocative, and youth-based country music revival. At the time, the interest among baby boomers for this type of music appeared to be a typical Southern California idiosyncracy. But it was destined to become a classic school of country, and things that are classic continue to influence and set a standard over time.

The Maddox Brothers and Rose

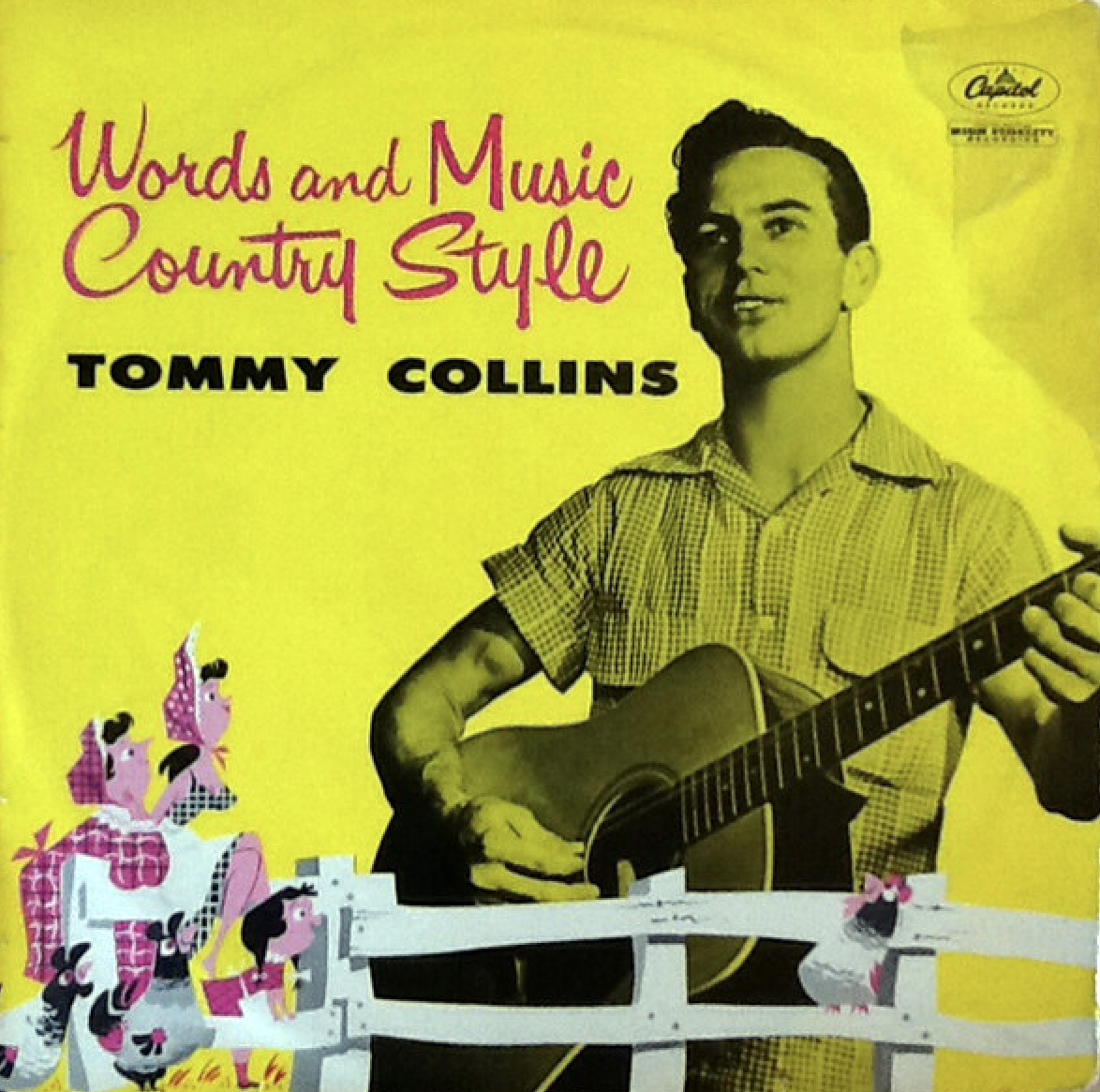

County music historians generally trace country rock to the California’s Central Valley/Bakersfield sounds of the Maddox Brothers and Rose, Tommy Collins, Wynn Stewart, Buck Owens, and Merle Haggard. Though these artists were not country rock per se, they would have a heavy influence on the country rockers. Their music was punchy and required a good, tight four- or five-piece band playing electric instruments. Bakersfield country still possessed that honky-tonk twang that ran counter current to the slick, polished, and increasingly refined Nashville sound of the same era. In the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, Nashville had forsaken much of the traditional country sound in an attempt to gain a wider audience. Back on the West Coast, however, “tele” riffs, pedal steel solos, banjos, and fiddles were still valued in country music. Bakersfield also added distinct electric bass and drums, which gave the music a certain hot-rodded feel.

Throughout the 1960s and into the mid-1970s, California, in particular the southern coastal region, became the proving ground for a new, edgy, provocative, and youth-based country music revival.

Bakersfield acts and country rock were also similar in the way they drew from California’s rich cultural and musical heritage. Present in both were hints of California’s early Spanish and Mexican ranchero tradition. Present was the “Forty-niner” spirit of adventure and wanderlust. Present was the mixed pain and optimism of Dust Bowl refugees. Present was the boom-town spirit of WWII and the post-WWII era.

But there were also sharp differences between Bakersfield country music and country rock—not so much in the musical approach and instrumentation, but more in values and attitude. Indeed, to borrow a term from the time, there was a “generation gap” between the two. When analyzed closely, these differences became more important than their similarities.

Tommy Collins

To begin, Bakersfield stood in proud defiance of Nashville’s control long before Willie and Waylon’s Texas outlaw movement of the 1970s. On the other hand, the young guns were indifferent to Nashville’s music machine; this in itself was quite a powerful statement.

Bakersfield artists were often products of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s. Country rockers on the other hand were more likely to be products of post-WWII affluence. Moreover, the music of Bakersfield had a ready audience in white, blue color, and working-class Californians. Contrast that to the young guns whose music was more egalitarian and whose long-haired life style drew fire from traditional country music fans.

The punch and grit of Bakersfield country could be traced to Elvis and other early rock pioneers. For that reason a few musical historians have included Bakersfield country as part of the overall country rock movement. But it was the Beatles who would separate Bakersfield from the young guns. Indeed, it’s well known that Buck Owens was a Beatles fan, but more than that he was a Hank Williams fan. On the other hand, the Beatles were huge Buck Owens fans, even to the extent that they recorded “Act Naturally,” followed by their own country songs like “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party” and “I’ve Just Seen a Face.” The point is that a Bakersfield artist like Owens enjoyed the Beatles, but their influence never became a major element in his music. The Beatles on the other hand would prove to be as important to country rockers as would the Bakersfield sound. Indeed, without either of the key ingredients of the Beatles or Bakersfield, country rock could never have been birthed.

Bakersfield artists were often products of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s. Country rockers on the other hand were more likely to be products of post WWII affluence.

The Bakersfield sound and its artists were compared and contrasted to the country rockers that emerged from Los Angeles between the mid-’60s to the early ‘70s. Let’s take a look at the first serious attempts to blend country into an existing rock ‘n’ roll format.

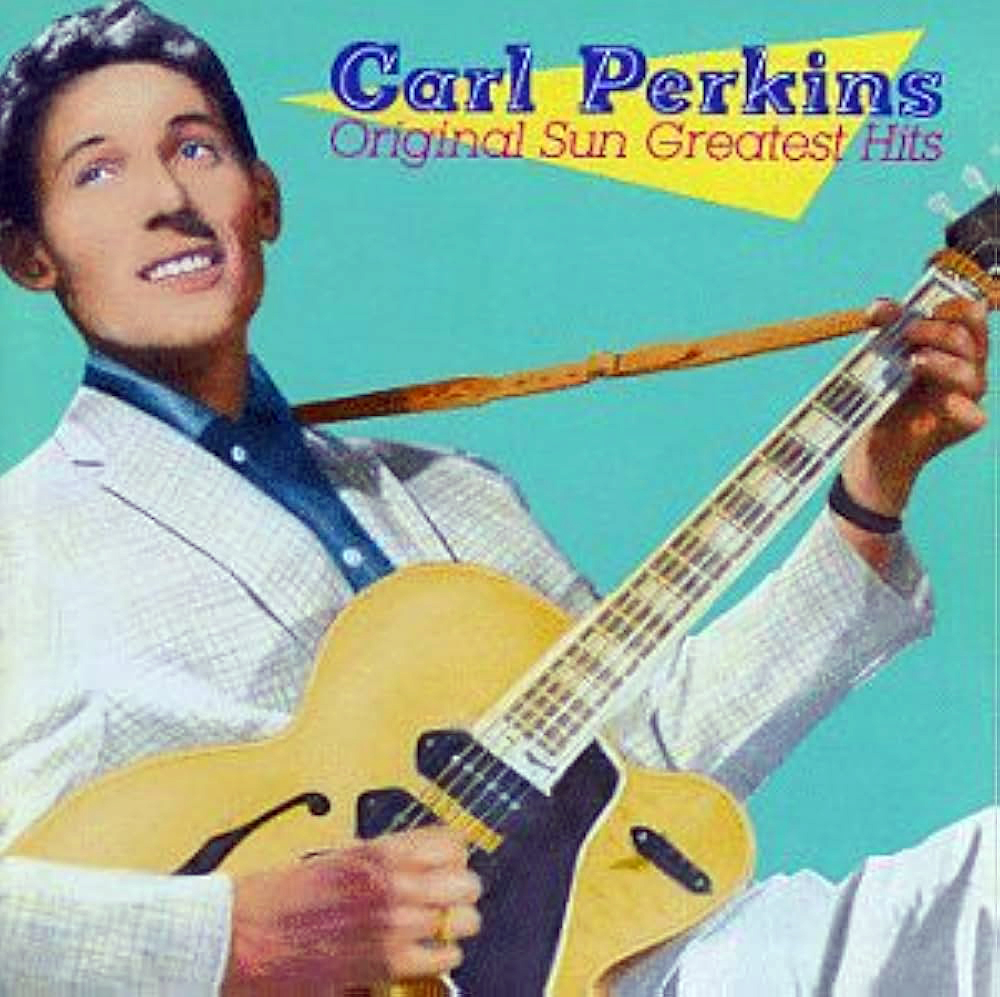

At its inception, country had played a major role in rock ‘n’ roll music. Early rock pioneers like Elvis, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and the Everly Brothers were all heavily influenced by country music. And how could they not be, considering their white, southern roots? Indeed, Sam Phillips’ Sun record label read like a Who’s Who of rockabilly.

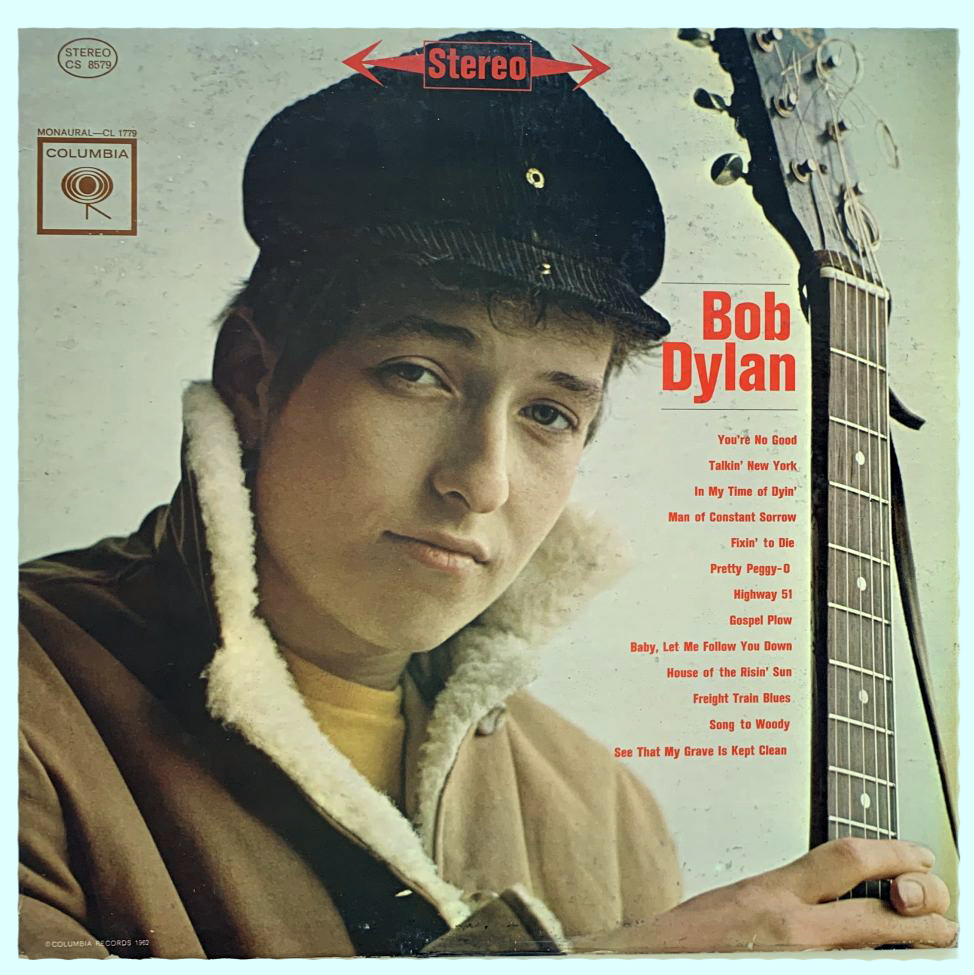

Buck Owens and the Buckaroos

Between 1959 and 1960 the first phase of rock ‘n’ roll had come and gone. Elvis was in the army, Buddy Holly was dead, Jerry Lee was in disrepute, and Chuck Berry was in jail. To fill the vacuum left by the absence of these giants, record companies manufactured the “teen idol.” About the same time acoustic folk music was gaining popularity. Groups like the Kingston Trio; Peter, Paul, and Mary; the Journeymen; the Limeliters; and the New Christy Minstrels became an alternative to the teen idol syndrome. Though most of the music produced by these popular folk combos was highly commercial, it nevertheless provided a link to the music of serious folk artists, such as Jimmy Rodgers, Woody Guthrie, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Bob Dylan.

And then there was bluegrass. Bluegrass, once considered a type of country music, had been shoved aside by Nashville in favor of its new slick, uptown country sound by the late ’50s. Gone from country radio were the sounds of fiddle, banjo, dobro, hot guitar, and high-lonesome harmonies. Though disowned by Nashville, bluegrass found a new audience among hard-core folkies.

Carl Perkins

What does this have to do with California country rock? Among the key figures of the California country rock scene, most would come out of folk or bluegrass circles. Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman, Richie Furay, Gram Parsons, the Dillards, Gene Clark, Clarence White, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou, et. al. were steeped in these musical traditions.

Now, to the influence of the Beatles. When the Beatles hit America in early 1964, it spelled the end for the acoustic folk scene. The Beatles reinvented rock ‘n’ roll by both borrowing from its past and creating a new future. As an electric band, the synergistic energy created by the Fab Four hadn’t been seen since the heyday of Elvis. But underlying the whole Beatle phenomenon was the band’s creativity. Because they wrote their own songs and developed their own sound, there was a solid core of strength, integrity, and creative depth, underneath their cute mop tops and cherubic features. Besides, creating their own musical gems, the Beatles borrowed from America’s rock pioneers. The music of Carl Perkins and Chuck Berry was reintroduced to an American youth who had forgotten or were too young to appreciate country-laced rockabilly when it first appeared.

Bob Dylan, 1962

In response to the Beatles, American folkies formed their own electric bands. The Byrds, Lovin’ Spoonful, Mamas and Papas, and Buffalo Springfield are prime examples of America’s answer to the Beatles. And though these bands enjoyed commercial success, at their heart was the spirit of American folk. By the summer of 1965, Bob Dylan had gone electric and had become a rock icon.

By 1967 strains of country influence could be heard in the music of many of these American folk-rock acts—harmonies, instrumentation, bona fide country licks, rural imagery, and rhythms. Before long, even their dress hinted at country as cowboy hats were seen perched atop the heads of Steve Stills, David Crosby, and Zal Yanovsky. Neil Young took to wearing a Buffalo Bill jacket. Beatle boots were replaced by cowboy boots. Soon albums contained flat-out country songs, such as the Springfield’s “A Child’s Claim to Fame” or the Byrds’ “Time Between.” The Lovin’ Spoonful got a top-40 hit with “Nashville Cats.” But these country cuts were not representative of Nashville at that time, rather they were akin to the punch and twang of Bakersfield.

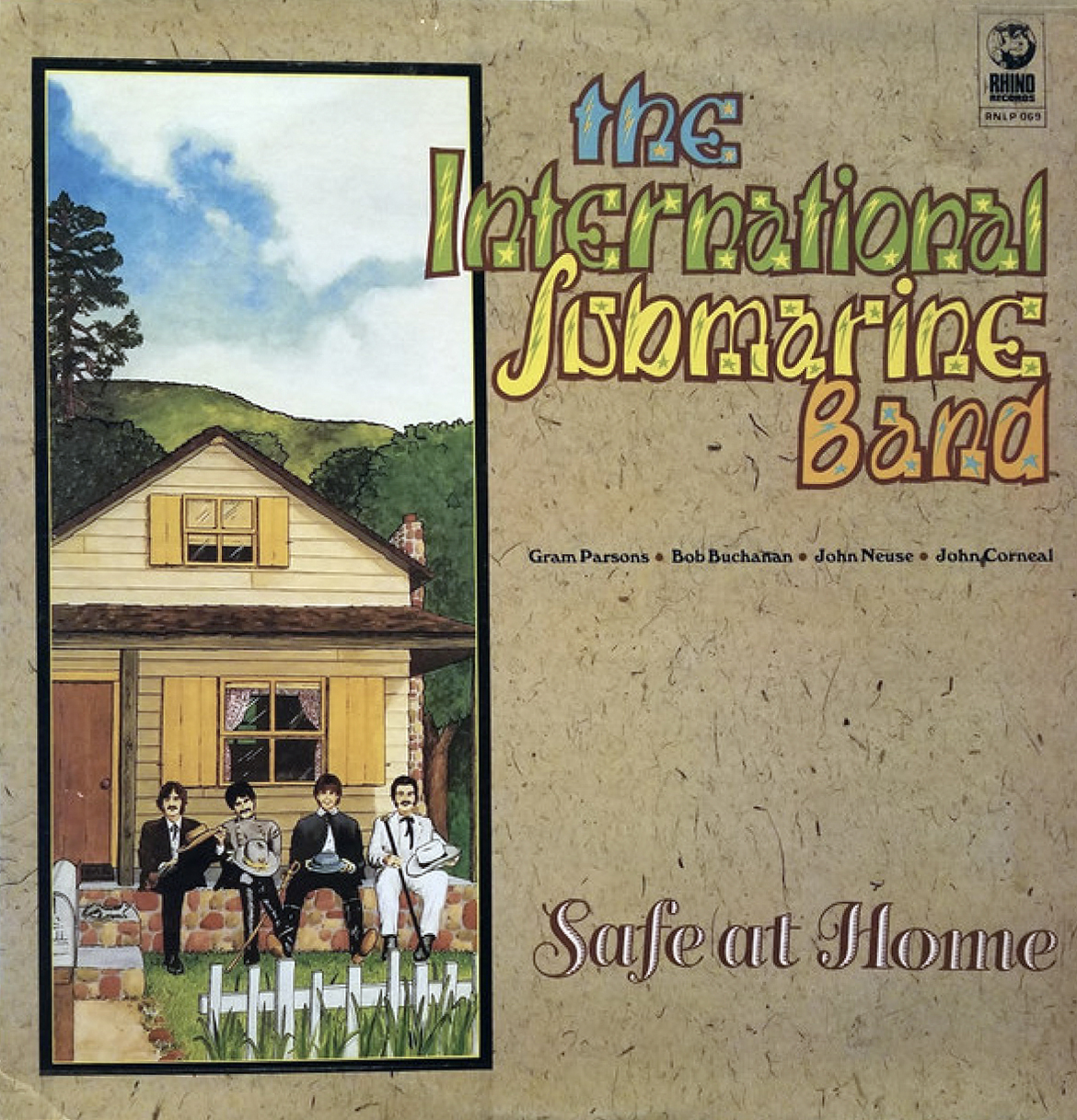

Gram Parsons & his International Submarine Band

Also, in 1967, Gram Parsons and his International Submarine Band was in Los Angeles recording a complete country album, Safe at Home. Though Parsons had joined the Byrds by the time of the album’s release, it marked the first total country album recorded by a long-haired youth-based band. Also in that year Gene Clark released his first excellent solo album after leaving the Byrds, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers. Though the album is more folk-rock than country, it is notable for boldly placing Clarence White’s country guitar licks and Doug Dillard’s banjo at the front of the mix.

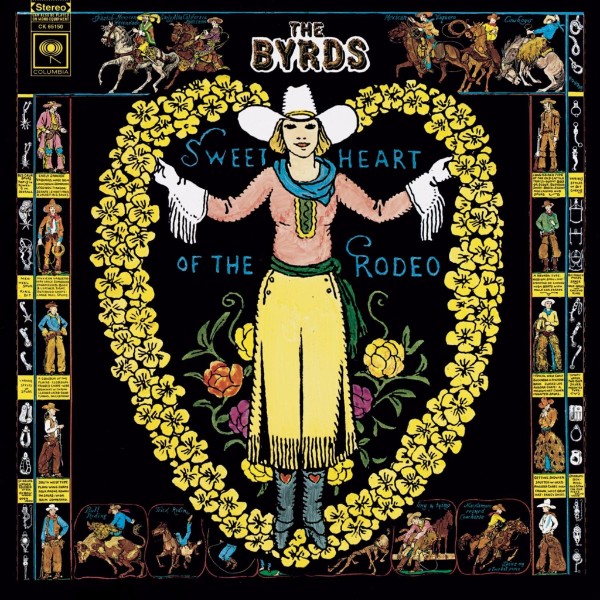

Though these Parsons and Clark albums were fine works, they got little to no popular exposure. As such, these works had minimal impact on imparting the virtues of country music to a rock ‘n’ roll audience. And though the Beatles had played rockabilly and country before, they could get away with anything. Then in 1968, the Byrds took the bold step in doing a complete country album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo. This was the first attempt by a renowned and highly respected rock band to commit a total album to country music. Though the Byrds had strong country champions in Chris Hillman and Gene Clark, it was with the exit of David Crosby and the addition of Gram Parsons that the group became a real country band.

The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo

Roger McGuinn once described Byrds’ albums as “electronic magazines,” with Sweetheart being a special edition. Certainly, the band had help from some great country musicians on Sweetheart as the credits testify; nevertheless, the album is unmistakably the Byrds. The album is a potpourri of classic country styles and themes. Optimistic gospel songs; melancholy drinking songs; and songs about outlaws, prison, and cowboys are all on Sweetheart. Styles ranged from proto-country Appalachian folk to ¾-time ballads, to upbeat 4/4 rockers, to honkytonk shuffles, to bluegrass. Though the Byrds borrowed songs from country artists like Merle Haggard and the Louvin Brothers, they also borrowed from Dylan. By doing this, the album had the ability to bridge their Baby Boomer listeners to more traditional country.

Parsons also contributed a couple of fine country songs for Sweetheart. This again pressed upon the listener that country music could be made for an under-30 audience. Ironically, Parsons believed the new album could be a vehicle for winning over the older and established country audience as well.

Sweetheart was a great traditional country sampler, while providing a promise as to the potential for a hipper form of country music. It was the Sweetheart Byrds that gave the green light to all the country rock bands that would follow.

Next month, Part 2 will explore the evolution of the country rock movement from the late ’60s to the present.

This article is a reprint from the March 2002 issue of the San Diego Troubadour, written by founding Troubadour member, the late great Lyle Duplessie. Lyle was an exceptional writer, gone way too soon. We miss him.