Featured Stories

Bob Dylan: A Complete Unknown

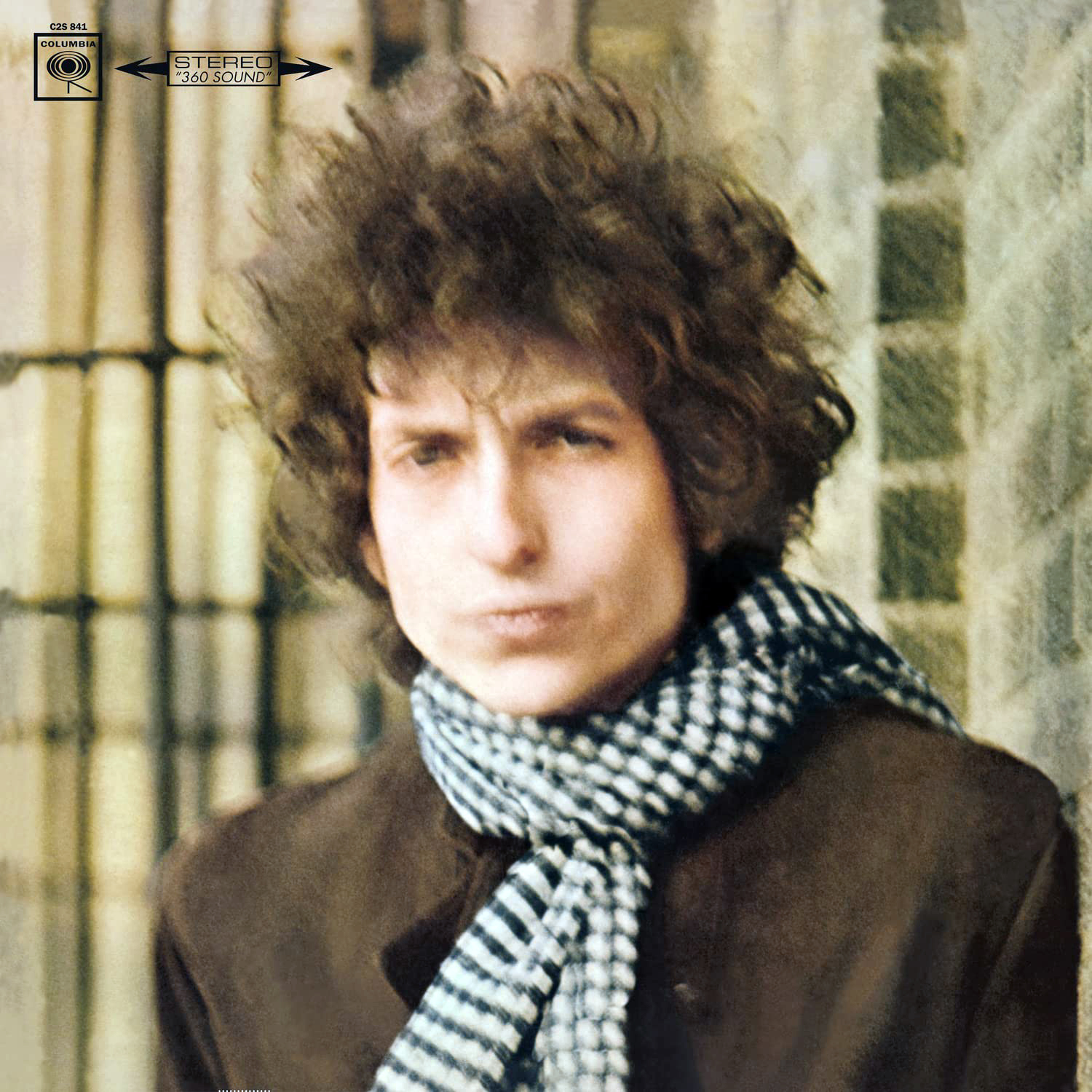

Bob Dylan

Exactly who Bob Dylan is remains a mystery to his millions of followers. It’s been estimated that over two thousand books have been written about Dylan since he emerged in the mid-sixties, a situation that gives us many versions of the who, what, and why of the former Robert Zimmerman. Coupled with the songwriter’s infamous habit of fictionalizing his biography, what we’ve had for decades are many personal Dylans. You could read him in any way that suited you. Dylan crafted a mystique by hiding the truth and fabricating what he thought was a better story. Even with the truth revealed over time, he’s remained a mystery, a man hidden in plain sight. This hasn’t prevented writers and filmmakers from creating versions of the Nobel Laureate. The variations on the known facts of Dylan’s story settle nothing, of course, and in fact compound the mystery around the man, a situation that only makes the icon more alluring.

It was reported in July of 1966 that Dylan had a motorcycle accident while riding in upstate New York. The tour was cancelled. He was a recluse for eight years after the accident, not returning to the stage until 1974. He remained creative during his radio seclusion, releasing his John Wesley Harding album in 1967, Nashville Skyline in 1969, and Self Portrait in 1970, but this wasn’t enough to stymie the musings on who Dylan was truly and what he was up to. The absence of interviews, concerts, and new paparazzi photos resulted in artistic expressions about pop stars either ascending to unreal heights of influence or who performed vanishing acts of a sort. Great Jones Street, a brilliantly etched 1973 satire by novelist Don DeLillo, tells the tale of an influential rock star named Bucky Wunderlick, who has burned out and finds himself approached, despite his seclusion, by promoters, fans, intellectuals, would-be gurus, and hucksters of all sorts, all of whom seeking approval and a blessing from the reluctant Oracle, a stream of hucksters who need to be told what to do. A figure as vast, vague, and finally overwhelming as Dylan, though, makes for rich premises on fantasies about rock musicians who reach a level of influence in society and who become political tools to nefarious ends. 1968’s Wild in the Streets, based on a Robert Thom short story and who also wrote the screenplay for the latest Dylan film, A Complete Unknown, is about an American political party that finds itself desperate to increase its power, with kingmakers seeking and getting the cooperation of an enigmatic and sullen rock star named Max Frost to convince the young fans to get involved in politics. In a sequence of events, the voting age is lowered to 14, Max Frost is elected president, and adults over the age of 30 are required to go to reëducation camps where they’re force-fed large doses of LSD.

More recently, we come to I’m Not There, a 2007 movie directed by Todd Haynes, which depicts Dylan himself—as we think we understand him—in bringing together different personae of the singer, each variation tweaked, twisted ever so, and re-contextualized in unexpected ways. The nonlinear plot reveals a series of narratives drawn from the legend and lyrics of Dylan, with different actors highlighted as the singer in one of his various personae, i.e., the doomed poet, as Woody Guthrie, rustic folksinger, and a doomed rock ‘n’ roll star. It’s an interesting project that plays around with the many personae that Dylan mythology has spawned through the decades, and the point of the movie’s divergent take on him seems to be that we’re no closer to uncovering the inner being of this quizzical figure. Take your favorite version of Dylan and enjoy it, love it, and may it add to your life in only the best ways.

Timothée Chalamet plays Bob Dylan in the new biopic A Complete Unknown.

With all the magical thinking about the meaning of Dylan, it’s a relief that director James Mangold’s biopic, A Complete Unknown, sticks with the best-known biographical arc associated with the singer. We meet him (portrayed by Timothée Chalamet), when he was first dropped off in New York and wandered into Greenwich Village, jean-clad, toting a battered guitar case. The world of ’60s Bohemia greets the man from Minnesota: coffee houses, poets, art galleries, street corner musicians, intellectuals, lifestyle avant-gardists—all real geniuses and posers alike—gathered in the few condensed New York blocks of the Village that comprised the free-thinking capital of America. And, of course, the folk music, the folk boom, the sweeping interests in traditional music forms, Civil Rights, and opposition to the Vietnam War. This was a world the young Dylan wanted to be a part of, one he’d come to dominate. It was a world he conquered and abruptly left.

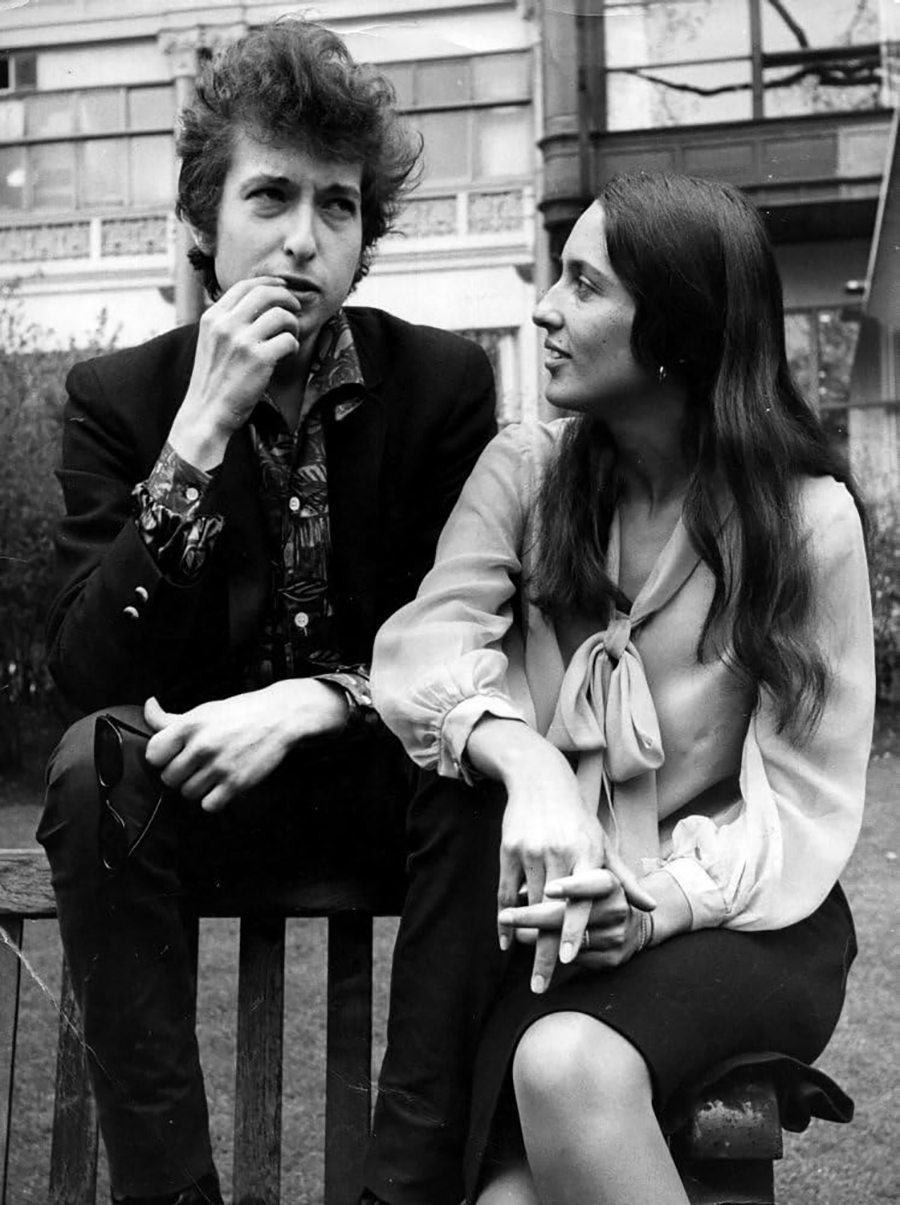

The movie is splendidly crafted, with Mangold’s direction taking us through the known events in Dylan’s early life prior to his 1966 accident, progressing from his arrival in New York through his meeting of his first girlfriend, Suze Rotolo (name changed to “Sylvie Russo” in the film); meeting Pete Seeger in folk legend Woody Guthrie’s hospital room, where the young Dylan sings the patient a song written in his honor; his early days at open mics and hootenannies, performing for benefits for civil rights and other lefty causes; meeting Joan Baez; and growing attention from the public and the media. Mangold and screenplay coauthor Jay Cocks (incidentally a former film critic for Time magazine) enliven the oft-told incidents with precisely the right amount of speculative dialogue, no speeches, no political rhetoric, and no exposition dumps.

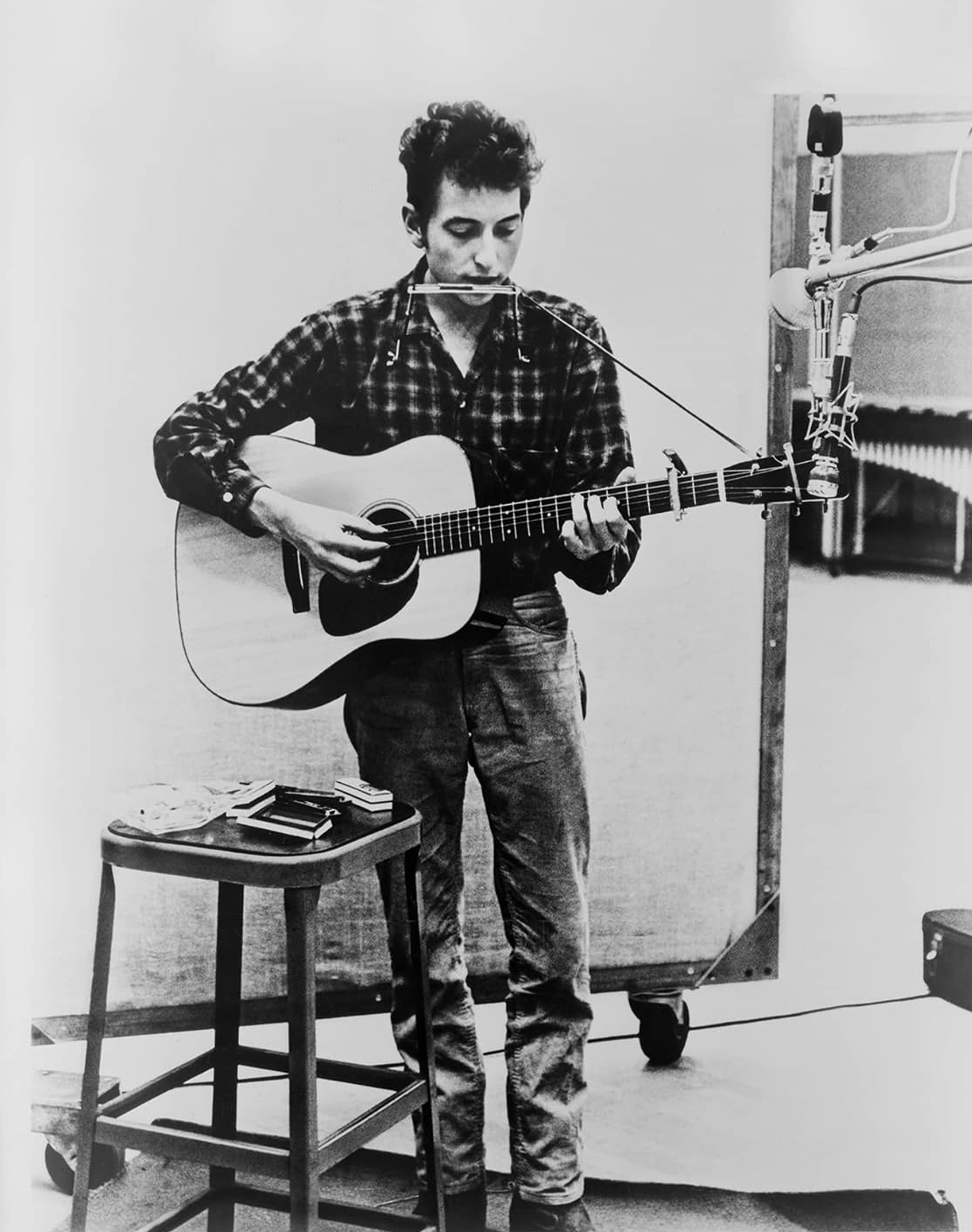

Dylan in 1965

The interactions among the singer and those who befriend him and come to love him are quirky, set in a natural rhythm of give and take. It’s no small accomplishment that the screenwriter restrains a desire to explain, hypothesize, or convert the Dylan saga into a weighty and unreal melodrama. There’s a natural, unforced progression here with telling scenes, well-known to Dylan completists, given the right emotional temperament. What might have been a segment ripe for overdramatization, such as when Al Kooper showed up for an electric Bob Dylan session for “Like a Rolling Stone,” preparing to play guitar only to be temporarily sidelined when he hears the red-hot fret master Mike Bloomfield play some snarling blues licks. Kooper knew he couldn’t compete with Bloomfield on guitar, so he insinuated himself behind an organ, insisting he had a terrific keyboard idea .Kooper had no such idea and was barely a keyboardist at the time, but when the tapes rolled, the musician’s poking and jabbing at the keys became an integral ingredient in one of the greatest rock songs. There were any number of grandstanding Hollywood clichés the filmmaker might have relied on to create this scene: loud voices, cartoonish facial expressions, and lots of rapid edits to enhance tension and drama, but Mangold maintains his sure hand. Obviously, an abbreviated rendition, there is no natural arch about the scene, only an intriguing showing of musicians and producers working their way through a problem.

A Complete Unknown doesn’t portray Dylan as a saint or would-be prophet as (maybe) some fans might have liked, and one of the issues they tackle with the icon is inconsistency with both who he is and how he treats those close to him. Well known for telling tall tales and otherwise fabulating about his upbringing and experiences prior to landing in New York, we see where the people he meets are awestruck at the apparent uniqueness of the young genius in their midst, only to have those closest to him become distressed and (perhaps) a bit disillusioned when Dylan’s accounting of himself is found wanting. He’s seen being duplicitous in his relationships with Sylvie Russo and fellow folk singer Joan Baez, an unfaithful lover and user of other people’s good graces to get ahead. Those who’d welcomed him into their world of folk music and left-wing politics witnessed the man they looked up to. By the time the film lands on the infamous Newport Folk Festival, where Dylan “goes electric,” his relationship with the traditional folk community has become tentative at best. He refuses to sing his old songs with Joan Baez when she attempts to get him to duet on “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Despite pleas from the crowd and Baez’s chiding, Dylan walks off stage. Later, as the noise from his performance with the Butterfield Blues Band creates a backstage argument, an incensed Pete Seeger attempts to take a fire axe to the speaker cords but is stopped by his wife. Dylan is booed after his three-song set but is coaxed back for an encore with only an acoustic guitar, where he sings, to rapt attention, “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue.” It’s a fact that Dylan did perform “Baby Blue” as an encore to the discontented crowd, and it works well as a subtle, cleanly presented symbol of Dylan’s leaving the folkie world, which nurtured him behind as his music became more raucous and rock ‘n’ roll and his lyrics ceased being topical and instead became surreal, Dada-esque, a landscape of existential confusion and wonder.

Dylan with Joan Baez

The casting is as perfect as one could want, with Edward Norton virtually disappearing inside his portrayal as Pete Seeger, with the entire ensemble, especially Monica Barbero as Joan Baez and Elle Fanning as Sylvie Russo (the name given the real-life Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s early love interest), inhabiting their characters with a particular reserve that makes their changing view of the Dylan character through the movie’s near two-hour length believable, credible as felt experiences. Early in the film, Baez watches Dylan in a folk club as his voice, his words, and his wise guy attitude captivate her. She’s aware that she’s witnessing something original and unique. Later, after their affair ends and his continual flaunting of his creativity, she tells him the morning following an unexpected one-night stand, “You know, you’re kind of an asshole.”

Nothing overplayed here, just a hard stare and some direct words indicating the end of something that was never going to progress to anything fulfilling. The storytelling style, the reined-in performances, and the uncluttered dialogue give the sense of the changing status of Dylan’s relationships with others. The disappointments of others in what the songwriter had become are tangible and powerful, effective without bombast or visual flash. A Complete Unknown is a finely wrought telling of a well-documented life, laying out the slightly fictionalized iteration of the tale that tells what we already know: that Dylan was an enigma in his early life and has remained an enigma ever since.