Featured Stories

A Tribute to the Doors’ Ray Manzarek

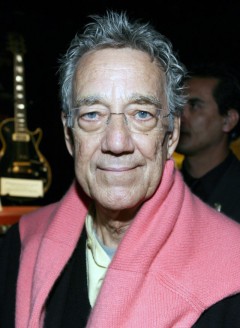

Ray Manzarek, 1939-2013

The Doors in their heyday (left to right): John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Manzarek, Jim Morrison

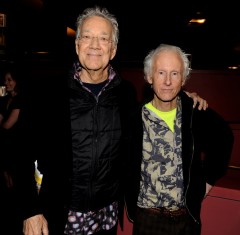

Manzarek with Robby Krieger in a recent photo.

You don’t make music for immortality, you make music for the moment, capturing the sheer joy of being alive on planet Earth… Everybody should live it that way.

–Ray Manzarek

In the summer of 1967 the Doors played the Anaheim Convention Center. I was 12 years old. I was completely transfixed by the band. Having an older musician brother, playing the Sunset Strip, signed to United Artist Records, and playing frequent live gigs made me no stranger to live performance.

I had never witnessed anything like these four guys on stage, capturing the audience with pure, inventive and passionate rock ‘n’ roll. Of course, Morrison was the center of everyone’s attention. It was hard to pull away from his near insane level of electric energy. But, sitting in the upper level allowed me the mobility to go from the side of the stage, to the back, and around to the front again. It was then the other three musicians also caught my eye. As the set progressed, it was clear, this was no ordinary band. Each musician brought something of their own to the sound. I didn’t know what to call it at the time, but what I heard Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger and John Densmore doing was adding a fusion of jazz to the psychedelic-blues proceedings. It was Manzarek who had me mesmerized throughout the show. He doubled Morrison’s vocal and seemed to be directing the music’s flow. As the concert ended, my life changed forever. I came out with an entirely new understanding of the possibilities of live musical performance. This was, in large part, due to the other three musicians on stage behind Jim Morrison and especially to the leadership of Manzarek, who died May 20, in Germany, at the age of 74 after a long battle with bile duct cancer.

Manzarek’s life was not only devoted to the music he was absorbed in, but also to its philosophical and spiritual underpinnings. As he said in a 1996 interview, the reason the Doors remained popular was because of freedom. They were, in his words the antidote to the bound and constricted times that we live in today. During the same interview, he also said the band defied categorization, which may also have been a reason for their durability. As can be witnessed through his writings and for those who knew him, Ray Manzarek’s spirituality came from his own natural compassion and love for others including so many fans and friends of the Doors. He always showed a positive nature even in the face of adversity, which gave substance to many of the ideals that formed his life and times. For Manzarek, love and peace were a part of his everyday experience, not just empty ideals. And it was also this love and compassion that helped him to discover the worth in the sometimes off-putting Jim Morrison when he first met him.

Morrison and Manzarek, both film students at UCLA during the ’60s, created music that would appeal to other UCLA film graduates, most notably Frances Ford Coppola, who famously opened his epic 1978 film, Apocalypse Now with the final track of the band’s first album, “The End.” The scene put the song and the band forever into the Zeitgeist of the Vietnam era that arguably lasted well beyond the ’70s in influence and scope. And without argument, so did the Doors.

If, as the surviving Doors have maintained to this day, they were a band of four equal parts, Manzarek’s contributions go back to his childhood in South Chicago, learning piano at seven years of age. Even though as he moved to Los Angeles to attend law school at UCLA, he was lured into film school and the eventual life-changing meeting with Jim Morrison. They met again after they had graduated, at Venice beach, a meeting that would impact American music in a way similar to the day Elvis first walked into Sun Studios in Memphis and Lennon and McCartney met in Liverpool. The band, formed in 1965, would be unlike any other in the already diverse and changing L.A. music scene. For Manzarek, the Doors would always be destined to stand out from the rest of an already outstanding class of musicians including Love, Buffalo Springfield, and the Byrds. His approach to the organ in rock performance was completely new to the form. In an effort to keep the balance among the four bandmates, he decided to forgo a bass player and instead recruited his feet for bass pedal during live shows.

While the lion’s share of material was written by Morrison and Krieger — few know today that Robby Krieger alone penned such classics as “Light My Fire,” and “Love Me Two Times” — Manzarek’s hand in arranging, especially in reference to the keyboard and the soundscape of lucid space he brought to the other members, gave them an unstoppable edge and enhanced their creative imagination beyond anything that was being produced in pop music at the time. Beyond all of this, along with Krieger and Densmore, he allowed Morrison to go unleashed in studio and performance. Unfortunately, that would lead the band down some mediocre roads in performance that would result in their near demise due to the controversial show in Florida with charges for Morrison of indecent exposure. But, without these lows, Morrison never would have hit the heights he did on their first three albums and later on Morrison Hotel and L.A. Woman. It was the support and structure provided by Manzarek that allowed Morrison to go wild and remain brilliant.

His post-Doors career confirmed his for brilliance as an artist, writer, and performer. He produced and performed on the classic 1978 debut album by the L.A. band X, extending his influence into the punk era. Even though the Doors officially broke up in 1973, they would reunite for the brilliant posthumous collaboration with Morrison on his recorded poetry album, An American Prayer. Manzarek’s other collaborations became the stuff of legend as well, including work with Phillip Glass, Beat poet Michael McClure, Iggy Pop, Echo and the Bunnymen, and an innovative spoken work-blues series with guitar great Roy Rogers, titled Ballads Before the Rain. He also notably wrote three books including his 1998 biography, Light My Fire, and two novels, The Poet in Exile (2001) and Snake Moon (2006).

In 2002, Krieger and Manzarek returned to the stage with the Doors of the 20th Century, enlisting the Cult’s Ian Astbury. In 2004, at the L.A. County Fair, with my 14-year-old son, I stood in a crowd of thousands and watched as the two musicians re-created their famous sound. On that day it seemed as if the clouds cleared and once again, “the night destroyed the day,” and the gods spoke and said, “There will be Doors.” And there they were like some cosmic miracle. It wasn’t the same band I saw that day in ’67, but it sure did beat the hell out of taking my son to see a tribute band. For the next decade they would tour as Ray and Robby, selling out venues around the world and effectively recreating that same sound I heard long ago. No other re-created band from the era would experience the same kind honor and success minus the sometimes overshadowing influence of their tragic and popular lead singer, who has been too often misconstrued as a the leader of the band.

With a summer tour coming up, Manzarek was still ready to go out on the road and keep the Doors’ music alive with Krieger and Doors’ tribute band lead singer, Wild Child’s Dave Brock. Sadly, with Manzarek’s passing, this era of his music has come to an end. The authentic sound of Doors music will no longer be heard on a live concert stage. That sound will be missed along the concert trail the world over.

But, the freedom Manzarek spoke about remains as does the myriad releases (and re-releases) that bear a full listen beyond the over-familiar songs still played on FM stations and satellite broadcasts today. The seven albums released by the band during their short productive years form the best in what we call Americana today, an impossible-to-define blend of music that is founded in the American experience.

Ray Manzarek was a key figure in breaking through the boundaries of genre. Without fear, he pursued the freedom and healing tribal spirit that music had to offer and contributed a wild, poetic, sometimes primitive celebration of American music in the midst of an age when most settled only for nostalgia over inventiveness. For me, I am still, somewhere inside that wide-eyed 12-year-old, and Ray Manzarek is still that young musician behind the keyboard with that uncontrollable lead singer, exploring the edge of his imagination and always inviting us to join him on the journey to the edge of the night.

Originally published in No Depression. Reprinted with permission.