Featured Stories

When Jazz Helped Integrate San Diego

George Nicolaidis (left) with Jeff Hamilton & Jim Plank. Photo by Holly Hofmann.

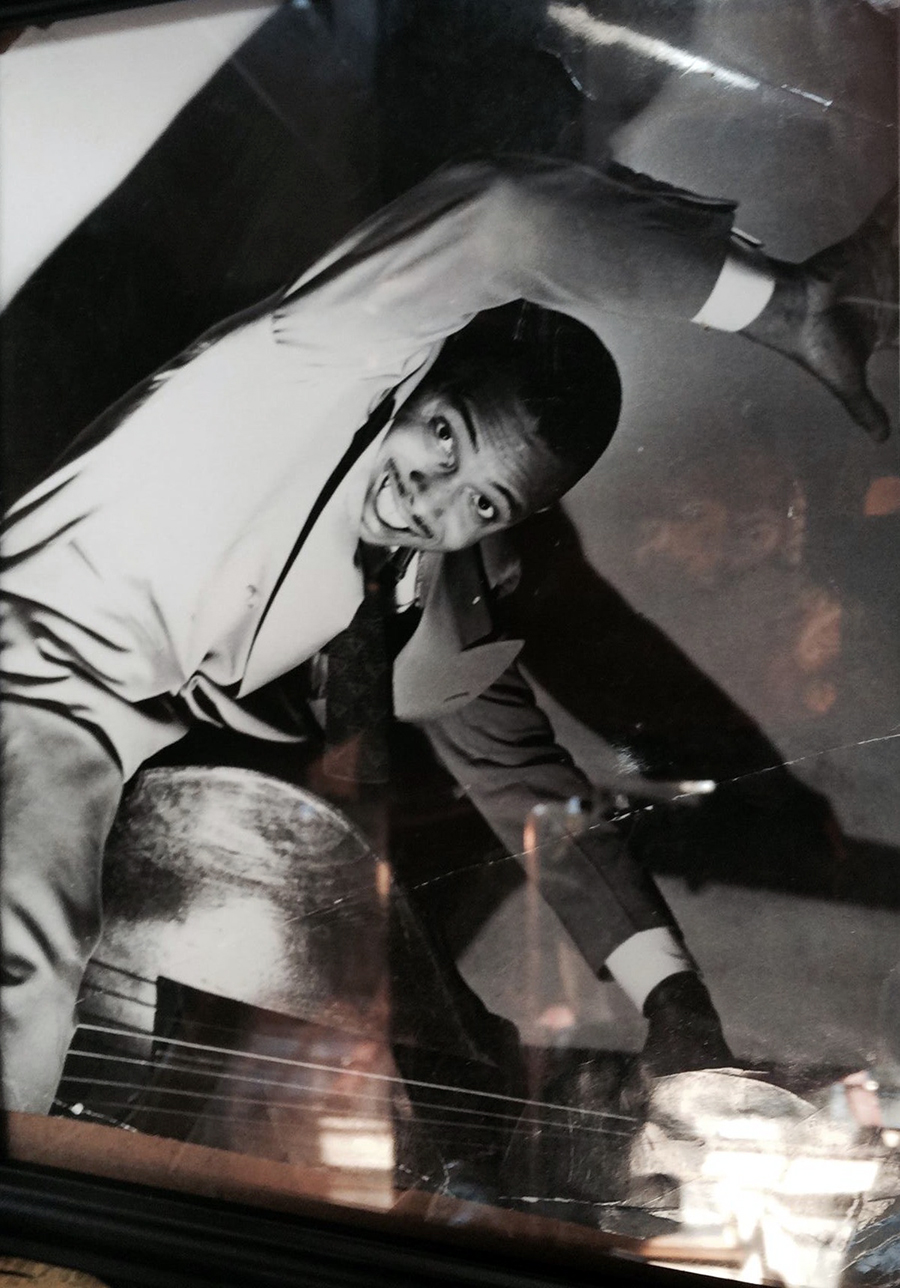

George Nicolaidis played with some of San Diego’s best jazz players in the 1950s and ’60s, frequently crossing the unstated but very real “color line” to sit in at black clubs. He lived through the slow process of desegregation and also witnessed San Diego’s explosive growth in the decades following World War II.

He sat down with San Diego Troubadour to talk about his life in music in San Diego.

My parents moved here when I was a teenager; I went to San Diego High School. I came just about then, from the New York City area, Jersey City, and upper Manhattan.

My parents moved around a lot—they were immigrants. They are from the west coast of Turkey, Anatolia on the maps. That was part of when the Ottoman Empire was in its last throes; the [Greeks] were there for years and years, going back to Alexander the Great. When my parents were kids, their families were purged out of there.

My dad was born in the 1890s. He came here in time for WWI. And they were recruiting. There was a pipeline for immigrant labor; he came through Ellis Island. There were shop stewards picking up these kids, and they became the bucket brigade for the subways. They would get paid and a place to stay.

He and his friends started working for the Stephens Institute in Hoboken as janitors. From that, they buddied up to start a place to serve food.

My mom is from the same village [in Anatolia]. She had an older sister who went to Constantinople and worked for the missionaries there. The British were there, and she became an au pair and eventually worked herself to France with the family. That was the route. She ended up coming to New York with that family and got a job at Macy’s as a seamstress. She put the first foot for that leg of the family. Then the sisters followed—my mom was younger; she had malaria and was quarantined on an island for five years.

She did the same route as the older sister, ended up going to Constantinople, and got hooked up with a family of German Jews, who were tobacco merchants.

A few years later, in New York, they had—and still had up until I was a kid—these societies of Greeks from Asia Minor, but the Asia Minorites thought themselves better because they thought the Greeks had been Balkanized by the Bulgarians and such. My folks met at a society picnic in the late 1920s.

I was born in 1937. I have one brother who is older. He’s 89, I guess; he was born in 1934.

Duke Ellington

I never had music lessons. But music was all in my environment, from the streets of the city. It was all Duke Ellington and Count Basie. It was all that kind of stuff. My dad messed around with a banjo, so there was ethnic music. The Top 40 then was Duke Ellington and Billy Eckstine. That was kind of the popular stuff, including Frank Sinatra and typical ’50s stuff.

In our household, we spoke Greek; English was a second language. My dad decided to open a storefront in a hole-in-the-wall kind of place with partners, then decided to go it alone. It was a place in Jersey City, and there was a restaurant on the corner. The timing was right because of WWII. This was right after I was born. The family business was an eight- or ten-stool restaurant that catered to the local folks. There was industry around there: the German Jews and the people who had been escaping from Europe were employed in the factories.

That was my gig. I used to go take orders. There was a hat factory, and they converted to the war effort. I’d go to these places and take orders for lunch. The school was just a couple hundred yards away; I’d come home for lunch and go get their orders for coffee and danish and go back with those deliveries. That was the family business.

My aunt, who worked at Macy’s, married and they ended up in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Then [they] heard about a place in California just like back home—with olive trees and where you could grow your own squash. So, they settled here in San Diego. They communicated with my mom and said this is just like the old country! By that time, my folks were ready to give up the restaurant; it was a grueling existence. We came here to San Diego in ’51 or ’52, around there.

I just came along for the ride. I went to San Diego High School. My brother went to San Diego State because he had already finished high school.

I was kind of the outcast there—that’s when I discovered Levi’s; everybody wore Levi’s and a t-shirt. I knew about blue suede shoes and slacks and a matching shirt. I was kind of a city slicker. The first few years were a culture shock!

We got to California, and I started hanging out with the guys, and they were talking about all this music and stuff. I was familiar with it, and they were trying to get a band together, and I had never played an instrument. I said, ‘I can do that.’ So, they said, ‘Well, come on over here.’ That just led from one thing to another, they were all trying to learn, and I was learning at the same time. We went down to the Memorial Gym. That was the whole theme then: garages and rec centers and church halls, where there were pianos. It was trial and error, listening to the records. All the music was by ear. The older guys knew some notation and stuff.

Nicolaidis said he decided to take a stab at drums as he and his new friends were teaching themselves to play.

Daniel Jackson

It was bravado, just doing it to hang out! In high school, I was in the same class with Charles Owens and Daniel Jackson. Daniel was already into it; he was sort of the guy everybody looked up to, and we were crass beginners. His older brother, Fred Jackson, along with Harold Land, Leon Petties, David Dyson, and Fro Brigham all had a working group at that time in the ’50s. Fred was 10 or 11 years older, and he was working.

What happened when we left high school was that I didn’t finish high school. I was a truant; I was leaving school early to work and was working at the car wash at 11th and C. Eventually I worked myself into a job making signs at one of the downtown department stores. I was always interested in art; that’s what I eventually studied at City College. Everybody else who worked at the car wash was indigent.

During that high school time, there were two choices: Either you went to work at Convair and you married your girlfriend, or you tried to get in the trades if you were white. The other kids would try to join the service. If you were black, you joined the service. Daniel and Charles joined the Air Force.

Charles ended up stationed at the March Air Field in Riverside and when Daniel got out, he came back for a minute then took off. He ended up with Ray Charles and Lenny McBrowne. Tilly, Lenny’s wife, was kind of managing them.

San Diego was a segregated place, musically, all through the ’50s up through the mid-’60s.

During the ’50s and ’60s Walter Fuller, who was a union official, crossed the line, which was Broadway. He was one of the few black union officials. The Club Royal was right there, the College Inn was on C Street, and they would alternate country-western stuff and the older swing bands. Club Romance was a few blocks down on Broadway. Zeke Mooney and Red Woods would play there. Adam Cato was a piano player, who played with Walter Fuller sometimes. Walter Fuller’s band was Fuller on trumpet, Gene Porter on sax, Preston Coleman was the bass player, the drummer was Leon Petties, and the piano player was Maurice Stewart. The vocalist from time to time was Lila Brown. Lila made the Evening Tribune. The vice squad was always present in these places, especially black clubs. She got busted for fraternizing with a patron at the bar.

Charles Owens got out of the service and went to Prairie View, then he went to Berklee in Boston, and from there he started hooking up with big bands. That’s how he got into Buddy Rich’s band. He ended up with Mongo Santamaria and Willie Bobo, and so did Daniel at that time. That’s how Daniel got hooked up with Willie. Then he got hooked up with Ray Charles, because David Newman got busted so they needed a tenor player and he got that job. When they found out he was using, he lost that job. He married Lenny McBrowne’s sister, and they ended up coming back to California. Then he went to L.A., and that’s when he was trying to work around L.A. to establish something.

And that’s when Cannonball Adderley was out here with a talk show! He had a TV talk show for a while! He was based in L.A. and was really kind of a mentoring and supportive figure. He would buy tunes of Daniel’s. Daniel wasn’t in good health then.

I was playing at that time. I was in the ’hood, out by Route 94. I was sort of a white sheep in a black flock. I was playing with bands here, locally. We had our high school band, and that band stayed together. And it got some notoriety as it was getting good. Ted Picou was already working in clubs, and he came on the scene and sort of mentored our band, taught us about harmonies and how to make our music more complex, more professional.

Charles Owens was in our band and a guy named Tommy Wilkins was the guitar player, who was the leader. We were the Kingsmen—Tommy Wilkins and the Kingsmen. Jimmy Wilkins was the singer, Kenneth Anderson was the baritone player, Leon Miller was the piano player. The other horn player was Ted Picou. We would augment the band when money was available. We were 18 and 19, but Teddy was already 22 or 23, so he could work in clubs. We couldn’t, but we’d go hang out outside the clubs to listen to the bands!

Walter Fuller’s brother was Gil Fuller, the arranger for Dizzy Gillespie’s big band. Walter had a hit in the earlier years—in the late ’30s and early ’40s—a tune called “Rosetta.” That was kind of a pop hit. [Fuller was singing in Earl Hines’ band.]

Joe Liggins & the Honeydrippers

We used to go around and listen to all these folks playing, and that’s how we got our music lessons. All the black musicians had second jobs, but Walter didn’t. Walter was full time. The Club Royal was six nights. Fro Brigham always kept his band, too, and kept his guys working. Hugh Parker, a trumpet player had a full-time job at the Post Office. Fro worked for the city, doing maintenance at Mission Bay. He’d work six nights a week. He always kept a band, and then he’d contract out these other jobs and put guys on them. He’d keep folks working like that.

A lot of local players never saw the light of day, so to speak, but they were just here in the ‘hood. On Imperial Avenue, there were a half-dozen clubs in the ’50s, with live music two or three nights a week. Most of the guys worked. And then the crossover white community would come down and hang out at these clubs. But the color line was Broadway. There were a few clubs on Fifth Avenue, like the Famous Door, with Eugene Watson, who was a wonderful piano player. Around the corner from there was the Monaco on E Street and Fourth Avenue. And then on Fifth Avenue between Market and Island there were three clubs: the Cobra, the Cotton Club, and across the street was the Zebra. Later on, at Fourth and Market, was the Crossroads. A lot of guys played there—Hollis Gentry and all the folks of that generation—which was a place for those guys to mature. The Douglas Hotel was on 2nd Ave. and Market; before that was the Cotton Club and before that the Harlem 400. It had three or four name changes. At 30th and Imperial was the Black and Tan, which now is a union hall. About three or four blocks up was the Ebony Hall upstairs where the infamous Big Jay McNeely came down and played in the street and the police tried to bust him.

Jazzville, 1967

At 26th and Imperial was the Paradise Club; the Elks Club had live music also. Down on 19th and Imperial, on the southwest corner, was Club 19; on 32nd and Market was the Oasis, which is still there. It’s a church now. You go up on Market Street, and that’s where Gentry’s Barber Shop was, on 40th Street, which was a community hub. Next to that was a bar that became Jazzville. James Long, a piano player who is now in Europe, and I started a jam session there on Sunday afternoons after the Chargers games. Those guys used to come and hang out. It was a place that people loved; it was long and narrow. The band was in the back, the bar on one side, and people just jammed in there. Then they expanded and bought the place next door. That’s when they started booking name acts. Dizzy came there as well as acts from L.A., big name acts.

Up on Federal and Euclid was the El Morocco. That was a jam session place, too. Then there was the Sporstman on Euclid and Logan. Charlie McNeil, an ex-Charger, owned that place. He played cornerback. In later years, David Grayson had The Safety; the music had crossed over and it was more of a fusion type that was on Imperial in the ’60s.

Lola Ward was the wife of Robert Ward, a lawyer in the black community; they bought the Trianon Ballroom at 11th and Broadway, it was upstairs. It was already established before they bought it. We’d catch Earl Bostic, B.B. King, and Benny Golson in high school. Benny Golson fronted the band for Earl Bostic. They’d play bebop at the beginning of the show, and then bring on the star for the hits. That’s how I first saw George Coleman; he was with B.B. King. They’d park the bus right there on 11th Avenue. They’d play bebop for the first hour, and then B.B. would come on and do his thing.

While San Diego was even more of a military town then that it is today, with the Naval Training Center still churning out tens of thousands of new sailors a year, Nicolaidis said that most of the dances on the local military bases were reserved for white bands.

Fro Brigham with Jesse Davis.

We worked a lot, but it was always sort of the white contractors. I worked for Tony Higgins. White players were able to get the gig on base and then would hire the black players. You could play weddings at the 32nd Street Club and North Island. Miramar was out of the zone! We had gigs sometimes over on Rosecrans at the old Naval Training Center.

There was another club over there called Club Mardi Gras, later on when the color line was expanding, which was on Scott Street right on the corner. It was down from the sportfishing place a block or two past Shelter Island. Leon Petties and Maurice Stewart had sessions there. Harold Land would come down. There was a bar upstairs where the sportfishing office was. Esquire Holmes was sort of a promoter who tried to put shows on there, but it never really worked out.

Hollis Hassel was a drummer who played with Fro. He was the first drummer with Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham down at the Sheraton.

Preston Coleman. Photo courtesy of Sue Palmer

When you go back further, those guys all used to work gigs near El Centro at a place called Winterhaven. In the late ’50s, people who were watermelon pickers and field workers would frequent the bars out there, all in a row on Main Street. Some of those musicians worked six nights a week there at Winterhaven, seasonally, whenever the demand was there. We’d also play at the Elks Lodge there in the black community.

I eventually worked with Fro and we both worked with Herman Riley, a sax player. Herman came to town from New Orleans, went into the service, mustered out, hooked up on the R&B circuit with Ivory Joe Hunter. When he married, his wife was originally from Florida but there were relatives here in San Diego, so there was sort of a connection. He ended up stranded in California and decided to come here. Herman had gone to Southern University in Louisiana, and Fro was also from there. The band teacher there recommended Herman to Fro, who was drafted and came here because of the Navy. Herman came, and he looked up Fro. That’s what Fro’s trip was… he was always sort of a liaison to hook people up with work. He hired Herman, and he was able to get a place here.

The same thing happened with a bass player who was also a connection to L.A. when Daniel was there. The bass players got out of the Marines; Victor Gaskin was from New York, but he was originally a guitar player learning to play bass. Victor eventually joined Les McCann. And drummer Robby Robinson was here, who was a Marine, also. They played around here locally in a big band at the Elks. Walter Williams, on trumpet, was in Lionel Hampton’s trumpet line with Clifford Brown and Quincy Jones! He was playing trumpet, Russell Campbell was playing trombone, Junior Foster on alto, and a guy named Kirk Bradford, who goes back to Jimmie Lunceford; he was sort of mentoring the saxophone section. That’s how the music education was!

Herman got his stuff together, his reading, how to play in a section, and Walter did the same thing. Fro Brigham at that time had stock charts—the Dizzy Gillespie/Gil Fuller stuff. Charles Owens was on sax, and Herman Riley was the other saxophone player. Victor was working as a mechanic. Herman and Leon were working in the kitchen at the hospital and Edgemoor Farm, a kind of nursing home for poor people.

Hollis Hassel would tell me stuff about how it was for him, Joe Liggins and Jimmy Liggins and the Honeydrippers. They had a hit record in the ’40s, and that was a little gig band that could get dates out of town; Harold and Hollis would also get work there.

There were lots of after-hours jam sessions and gambling places, where there would be little gigs there. There would be jam sessions in Tijuana, the Capri Club on the main strip.

Harold Land

I lit out of here in the early ’60s. I went to Minneapolis in the mid-’60s. I went to graduate school there. That was a great episode in my life, it was the most musical! I played music there from the day I arrived until I left two years later. Minneapolis was jumping! It was like Tijuana, bars right next to each other, strip joints, and there was competition for the hippest strippers. We worked with the strippers playing “Caravan” and “Night in Tunisia.” Some great bands, great musicians. I thought I was going to the end of the world and ended up working six nights a week! Paul Butterfield’s band were just getting started! Bobby Lyle was there. He was a wonderful piano player. After that, I went to Europe, that’s where I saw James Long again. By that time, he was in the service. I went to Germany, where he was stationed, and we got to hang out. He eventually came back here, and he taught school here for a while, then they decided to go back. That was a good move for him.

In the late ’60s, I ended up back here. Sorta been here ever since. By that time, the whole scene had changed; integration happened. The black community was sort of brutalized. Just dispersed. It was black-owned businesses and community before that; it was one to one.

The whole scene changed; you needed to create a spectacle; music and entertainment merged. Music as an esoteric experience kind of got thrown by the wayside, acoustic music in an interactive environment. Rock ‘n’ roll fulfilled its need. What happened to more complex music is it is seen as too intellectual. It moved out of the mainstream and wasn’t accessible anymore because the environment for it wasn’t accessible! The environment was different.

Teddy Picou did a thing with Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson for a while. Johnny Otis was a contractor himself: he had all these groups he’d put together and he’d keep these guys working. Johnny “Guitar” Watson would come to the gig early and play “I Remember April” and play all these bebop tunes with the band before he did his show. They would all intermingle; James Brown and the Flames would come down to the Douglas. It was all that crossover stuff. Teddy would do things with Johnny Otis.

San Diego at that time used to run on the 1st and the 15th, because that was the military and civil service paydays!

Carl Evans Sr. was a sax player in the Navy—there were a lot of guys in the Navy who came out of the black community. Carl Evans Sr. and I used to play gigs together. He was a connection to the military clubs. His other son, Michael, is a drummer. Ronnie Stewart, Hollis Gentry, and Nathan East were all in that generation. By that time the schools had all changed. Lincoln High was being built when I was high school. That kind of separated the community. Then they started building east of Euclid; that’s where you get Skyline, then there was white flight out of that whole area, from Valencia Park. That’s where Hollis Hassel lived as well as James Long’s family. That was going on in the ’50s. There were still covenants where blacks couldn’t buy houses. People wouldn’t sell to black families north of Market Street.

Yale Kahn had a place called the Chuck Wagon on Midway and Rosecrans in the shopping center. Michael Dean, the hypnotist, would perform there. Art Hirsch built the Roaring Twenties out in El Cajon, which was a bowling alley! John Guerin was involved out there for a minute, as were Gary LeFebvre and Joe Foss. There were clubs that opened up in bowling alleys, which were mimicking the lounges in Vegas. Those were some of the gigs that were available. There was one in National City.