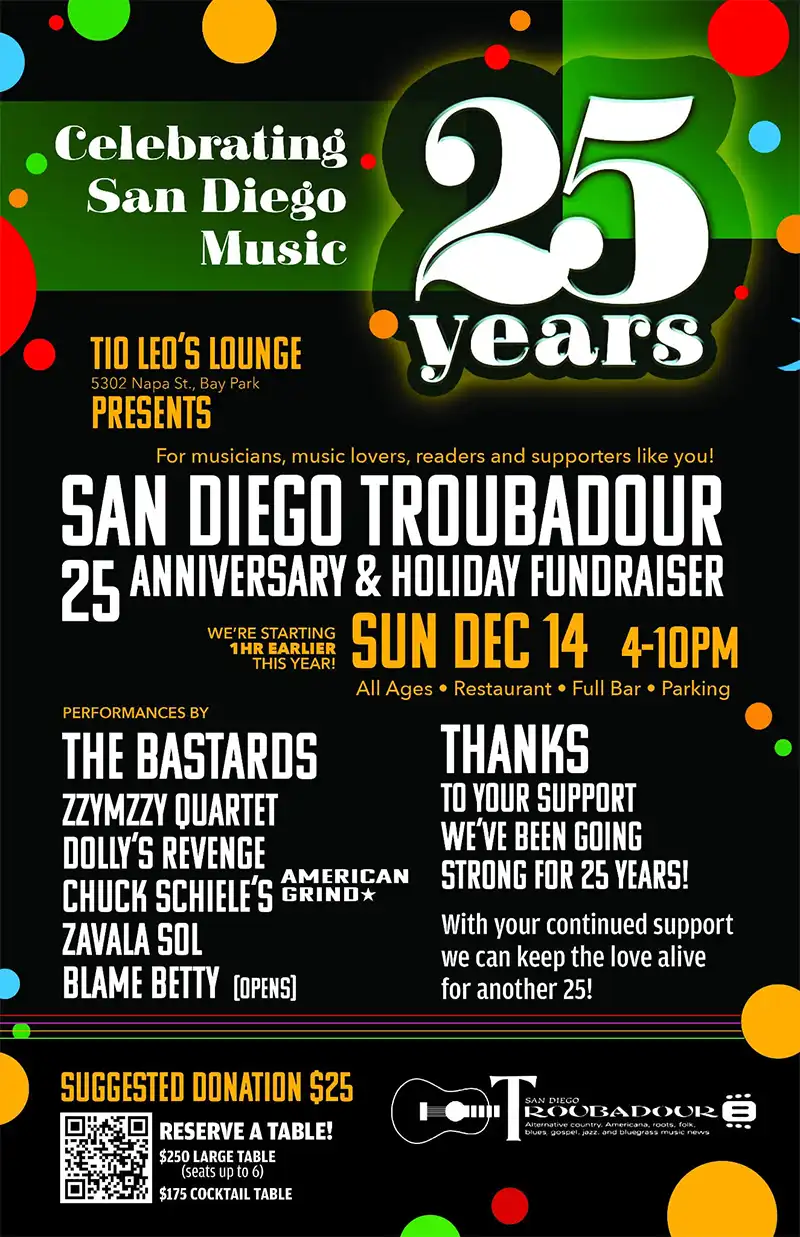

Featured Stories

In Praise of Brian Wilson (1942-2025)

Brian Wilson

Brian Wilson died on June 11. It’s not a bold statement to say he was one of the indisputably great artists of rock ‘n’ roll. Any rock pantheon that lacks his name is no pantheon at all. His work featured the most graceful and intricate melodies wedded with choir-boy vocal harmonies, a worldview that wished everyone could live the particularly American dreamscape of California. He was a man who heard sounds others couldn’t and was able to lay them out, obsessively, for audiences in a collection of brilliant music. He was an artist who changed the way millions—musicians and audiences—thought about popular music. Plainly, he was someone who cracked the code on new ideas of what was considered a good time and literally changed the world in doing so. Wilson changed how a generation heard music, and he was instrumental in changing how others created it. He was a prime mover in the “Youthquake” that would make the world we lived in more exciting, dangerous, experimental, and open-ended. This wasn’t something Brian Wilson set out to do. All he wanted was to follow his bliss and pay attention to the Muse that appeared to direct his best thinking.

What I remember about first hearing the Beach Boys’ anthem “Surfin’ USA” was that it was March 1963, I think. I was a ‘tweenager in Detroit, Michigan, and there was snow on the ground, the streets and sidewalks coated with dirty slush. Icicles still clung to houses and telephone poles. “Surfin’ USA,” a reworking of Chuck Berry’s sock hop classic “Sweet Little Sixteen” by Beach Boy leader Brian Wilson, was blasting out of a small transistor radio sitting on a kitchen lunch counter from top 40 station WJBK. The magic came through the static, I thought; it had great vocals and a killer guitar sound. But there was something more. The lyrics, mostly by Wilson, extolled the glories of catching waves with waterman lingo, with additional credit to the band’s lead singer Mike Love for a chorus amounting to call-outs of the best surf spots. It’s a tempting inventory of where the water hits the shoreline in full glory and power:

…Haggerties and Swamis (onside, outside, U.S.A.)

Pacific Palisades (inside, outside, U.S.A.)

San Onofre and Sunset (inside, outside, U.S.A.)

Redondo Beach, LA (inside, outside, U.S.A.)

All over La Jolla (inside, outside, U.S.A.)

At Waimea Bay (inside, outside)

Everybody’s gone surfin’

Surfin’ U.S.A…

A prophetic verse, in a way. To this day I don’t surf and neither did Brian Wilson. The Beach Boys’ music, specifically that of main songwriter Wilson, mustered fantasies of forever sunshine on golden beaches surrounded by beautiful girls in bikinis and guys and dolls catching a ride on longboards upon high-cresting waves that curled majestically to the sandy beach. That’s what that 11-year-old dreamed of. Wilson was ten years older, age 21, when “Surfin’ USA” was released, and though he didn’t learn to surf himself, the SoCal native learned about the culture from his younger brother Dennis, who became drummer for the sibling-dominated group. Brian Wilson became enthralled with the culture—the style, the lingo, the innocence of the easy-going ethos—and soon enough was composing paeans to the burgeoning sport.

The stories I’ve read indicate that Wilson’s toes rarely, if ever, trod a surfboard’s waxed surface. Being in a geographically critical area when white surfers brought the sport from Hawaii to the mainland, he composed a body of musical brilliance that introduced the rest of America and the world to the mystic wonder of California beach life. “Surfin’ USA” hit the charts in 1963, and nine years later my family drove across the country from Michigan to the West Coast, taking up residence in a town, name-checked in the song’s chorus: La Jolla. The legacy of our parallel paths resulted in two seismic things: the first being Brian Wilson’s avocation to capture the effervescent harmonies and tones he heard in his head onto record and have the magic embedded deeply in the Beach Boys’ singular work. The second was my eventual discovery of a world, soundtracked by the Beatles, the Stones, and Dylan, a world bigger than I imagined as a teen cloistered with a collection of 45s in my room during the harsh Midwest winters and sweltering summers. The second accomplishment was personal, yes, but it was seismic considering that the upgrade to my sense of things greater than myself occurred 62 years ago and that now that I’m edging just days away from turning 73, I remain intrigued, nearly overjoyed when good things occur. Wilson and many others were mentors of a sort, reinventing music forms, sounds, backbeats, and lyric alertness in ways that grasped a generation’s fancy.

The late jazz critic Whitney Balliet used the endearing phrase “the sound of surprise” to describe musical improvisation in its boldest and highest execution, and though Wilson was writing music using a different vocabulary, the three words present us with what the musician and composer’s body of work was: an expression of surprise, finding nuance and quirky-but-alluring side routes in melodies, baffling tone poems of unexcelled vocal harmonies, oddball middle sections, gradually intensifying wells of delicately layered sound shadings. Beyond this was the unshakable feeling of the artist himself being surprised by the music he was putting forth, the bits and pieces given to the famed collection of Los Angeles studio musicians called the Wrecking Crew, woven, stitched, and embroidered into the kind of complexity—subtle but listener-friendly—that widened the soundscape of pop music radio. One proceeds into these descriptions at the risk of reducing a great artist’s work into a slender set of categories, but it’s not presumptuous to say Wilson didn’t wholly abandon the themes that informed the Beach Boys’ initial string of hits, which were innocence, fun, live and let live, good weather, and good vibes. Back to the first verse of “Surfin’ USA,” where the singer speculates what it would be like “If everybody had an ocean”…

If everybody had an ocean (ooh)

Across the U.S.A. (ooh)

Then everybody’d be surfin’ (ooh)

Like Californ-i-a (ooh)

You’d see them wearing their baggies (ooh)

Huarache sandals too (ooh)

A bushy bushy blond hairdo (ooh)

Surfin’ U.S.A. (ooh)

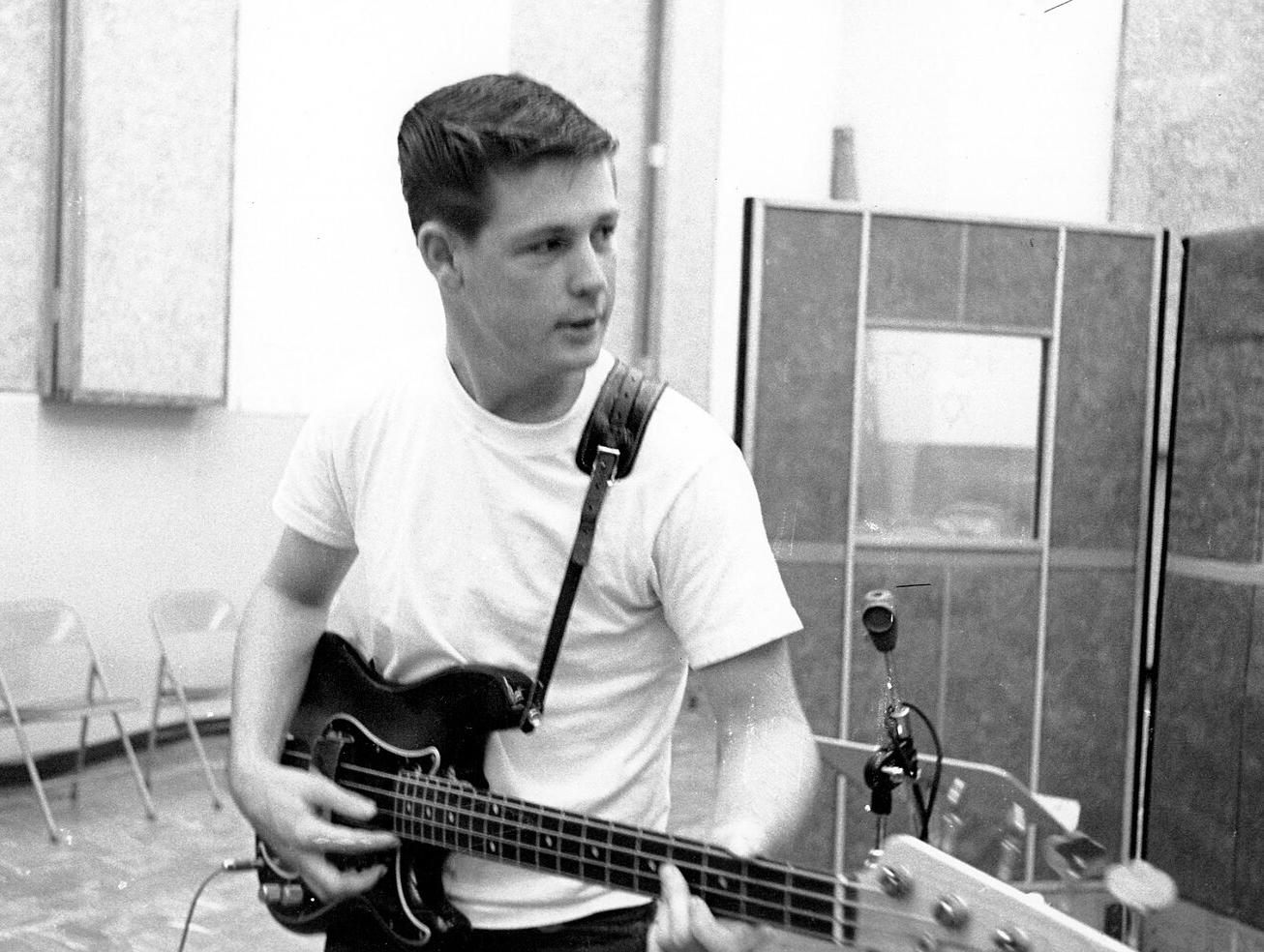

Wilson in the studio.

It seems sophomoric, but it’s worth noting that this dreamy hyperbole expressed a practical utopian spirit. It was a naïve but profound worldview the Beach Boys expressed quite a while before a generation told us that “all you need is love” or Scott McKenzie extolling his listeners to “wear flowers in your hair” if one made a pilgrimage to Haight-Ashbury. Wilson and crew hypothesized that if all of us had our very own ocean, the lot of us would focus on what’s important and get busy getting in the water and seeking a wave to become one with. This is a kind of spirituality, I think, where we return to the water from whence we came to experience the unfiltered miracle and thrill of feeling a part of the world as it dynamically moves, returning to one’s life on land again to do good work, only to “get into the water” again, to replenish the spirit and joy of feeling alive. A naïve way of going through one’s life, perhaps, and honestly, not all who surf are saints. The best of us can be reprobates and scallywags, at least briefly. But the surfing epiphanies Wilson felt early on continued through his lifetime as his music continued through different turns and emotional states. Freedom, serenity, peace, the capacity to be surprised and amazed—these were the burning fires in Wilson’s work, musically and thematically. He continued his search for the kind of feeling many might have thought was slipping out of our collective grasps, and it was wondrous for six-plus decades to follow his muse, to gather and record what he heard, adding exquisite and more intricate melodic structures and a near-Zen lyric simplicity that sought a precise and shining expression of the moment he was in. It’s well-known that Wilson had a lot of noise in his head, which crowded out the sublime melodies he heard, diagnosed with a schizophrenic disorder, subject to outbreaks of paranoia, problems made worse with the era’s defining plague of drug abuse.

Wilson & the Wild Honey Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hall in London for the premier of Smile.

We can speak at length of financial feuds within the band, bad management, eccentric antics, isolation from the world, incomplete album projects, a protracted period when he was literally taken hostage by controversial therapist Eugene Landy, who muscled his way into the songwriter’s business affairs… we could talk about it all, dissect it, speak of Wilson’s travails in several dozen ways, but doing so would put a cold sheath over this great artist’s music. The music prevailed. Wilson recovered to varying degrees, most notably with Brian Wilson Presents Smile, a 2004 recreation of the legendary Smile album, which Wilson abandoned in 1967 because he thought the project was somehow cursed. The release was a hit with fans old and new, and, buttressed by rave reviews from flabbergasted critics, the project reveals what the intended sequel to The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds album would have been like: an adventure in new sounds and textures and brilliantly crafted harmonies, ethereally crooning the poetic esoterica of lyricist Van Dyke Parks. It was an art-rock of particularly American designation, a restoration of a masterpiece to the highest ranks of greatest albums ever made.

Zen was mentioned earlier, and it’s appropriate to think briefly on Wilson’s minimalist masterwork, “Good Vibrations.” Broadly, Zen is a school of Buddhism that emphasizes achieving enlightenment through meditation, self-contemplation, and intuition rather than faith and devotion. It focuses on direct experience and perceiving things as they are. Brian Wilson, raised Presbyterian in Hawthorne, California, embraced the counterculture of the mid-’60s. Though not a practicing Buddhist, he felt the vibe of the time and ideas of free love and higher consciousness. He shifted his focus from surfing to seeking a unity of mind and senses, connecting with a greater sense of Totality. He was fascinated with the direct experience of the world, without abstraction or theory, and “Good Vibrations” was a tone poem of gliding grace, an imagist poem of being in what’s routinely called the “aha!” phenomenon, when the world in front of you is revealed as it is, free from mental clutter.

The Beach Boys in their heyday.

Wilson pursued what the American philosopher John Dewey termed “the aesthetic experience,” the state of full engagement with the world and discovering unique ways through an experience. We can be honest here and realize that the composer genius was neither intellectual nor wholly in search of divine knowledge. He was a sensualist creating sound tapestries that would ease a mind rushing with ideas odd and confusing, making an art that would return him again to an elevated tranquility. Superficially, “Good Vibrations” is simply the admission of one man to another that a woman he’s seen but barely knows gives him a positive feeling, a kinship, an attraction he doesn’t quite know what to do with but intends to explore deeper, experience deeper, come to know full well what these new “good vibrations” are. It’s a search for meaning, a meaning found outside his own inventions and in the world with another person who invites him to have a parley that is mysterious and profound. It’s the sweet seduction of the innocent, we might say, and we might think this is a naïve narrative leading to mere sexual awakening. Understandable, but we hear the words—simple, declarative statements of wonder—and we hear the voices that sing them, arranged in delicately contrasted layers, low, middle, and high ends of the vocal range rising, coasting on an ethereal stream. The effect is marvelous, one of a kind, the plain speech of the Beach Boys blended with Brian Wilson’s brilliance for symphonic impressionism on a small scale. This song is literally an orchestration, presented in short but effectively placed sequences that bring their own euphonic nuance to the simple glee of Mike Love’s lyrics. An astonishing effect, an element that makes “Good Vibrations” a masterpiece. The young man describing his need to understand what he’s feeling with no barriers is of itself unmoving, but combined with the music, it enlarges the description, sonically dramatizing what words alone struggle to get across.

Toward the end of the song, the choir-boy harmonies arise as if they were a sudden blast of brilliant sunlight burning through a dark cloud layer, revealing everything, radiating things profound and nearly unspeakable. Those voices, shifting through keys and wordlessly trilling into the fading light of sunset until the song finally, slowly goes quiet, as though to slumber until the next day arrives. This song sees nothing less than a prayer that these moments remain with us and that we might rise to a new day with open hearts and clear minds. Brian Wilson struggled for those moments, to express them in music and share them with generations that still find magic in his transcendental tunes.