Unsolicited Advice

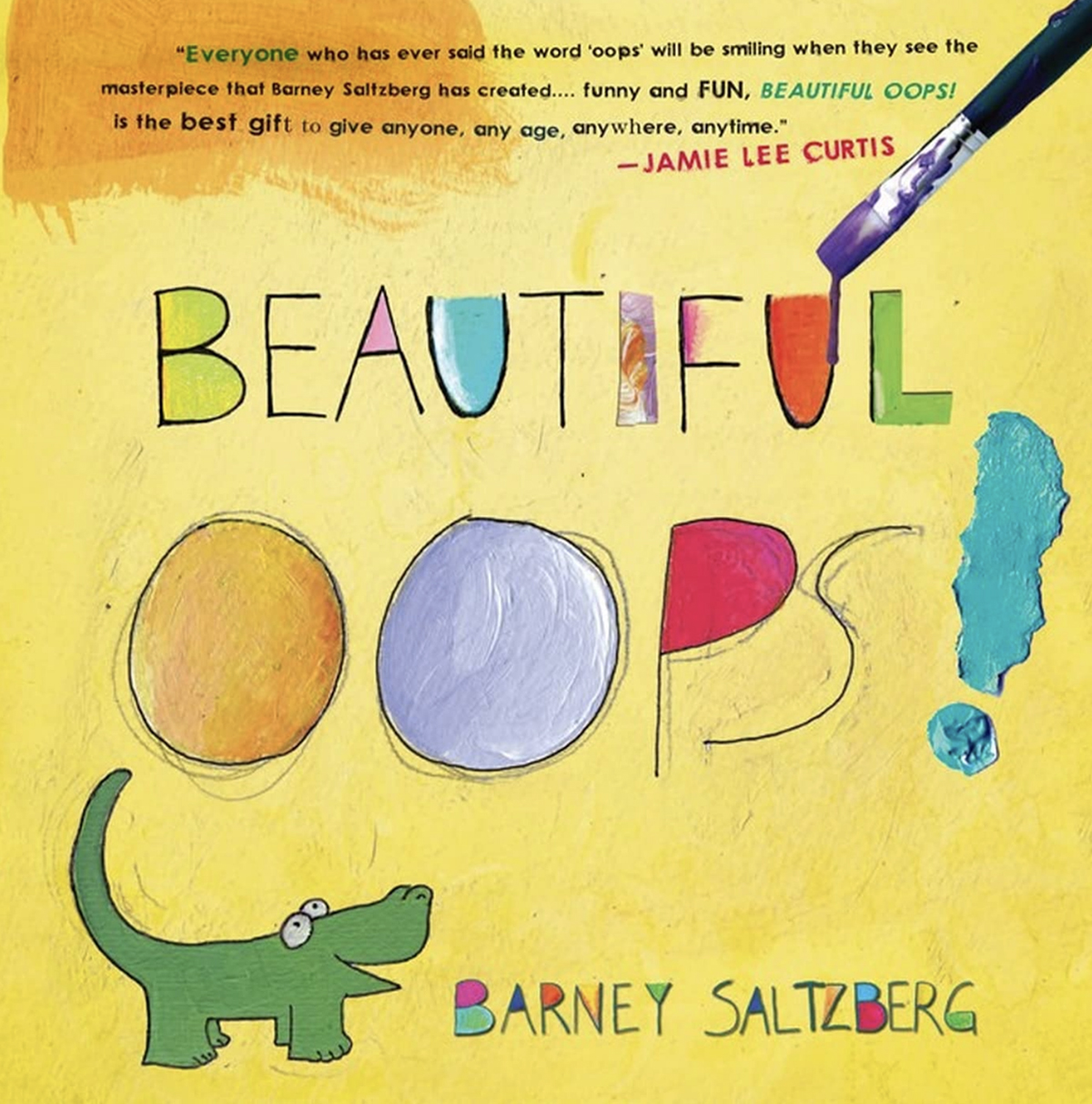

Magic Words, Part 2: Beautiful Oops

When my son was little, he came home from elementary school and started work on a painting he’d learned the technique for in art class. He was following certain procedures and templates (I don’t remember what), obviously something that had been modeled in class and excited to show off this new knowledge. Then…splip splip splip. Paint from the brush dripped onto a “finished” section of the painting, six-year-old style, basically undoing all the work he’d just done.

My brain leaped into parenting mode, preparing to help get him started on a new painting and up to speed with the least amount of turmoil and frustration.

But it was unnecessary. My son looked at it, shrugged, and said, “It’s a ‘Beautiful Oops.’” And he continued without a second thought. The finished painting was beautiful, much more interesting than the template version would have been. He was proud. Ms Y, his art teacher, by sharing that term with them, had given him and the other students a gift that would serve them throughout their lives. It turns out it was from a book she read to them one day.

Songwriters and other creative types know all about the Beautiful Oops. This the “mistake that makes the song (or painting/invention/poem/experience).” But for most of the world, a mistake is sabotage. It’s soul-crushing, momentum-ending, productivity-sapping. Today I want to encourage you to see the unexpected as an opportunity to get beyond yourself, to use the universe as a coauthor and embrace the outcome.

I have written songs for as long as I’ve done anything in my life. In fact, except for eating/sleeping/breathing/being incredibly charming, it’s the thing I’ve done the longest.

As any creative person will tell you, the “generation” stage is the most precarious. There are dual sensations of exhilaration and despondency—the former from discovering this magical buried treasure, and the latter from feeling, with certainty, that you are just not up to the task of birthing it into the world.

And then, without fail, it will happen: you’ll play the “wrong” thing—a chord you didn’t mean to play, or the wrong version of the “right” chord, or the wrong section of the song, or some Hail Mary giving-up of a hand-slam not even meant to be part of the writing process. And guess what? It’s perfect. It’s the exact thing the song needed to get over the hump of inertia and self-loathing. Even if the hand-slam itself doesn’t stay, the energy-change behind it turns out to be the crucial element that cracks open the rest of the song. Or the specific collection of notes you “arbitrarily” hit suggested the direction the song had to take from there. What are the chances?

Well, I’d argue they are 100%. The unknown and uncontrolled are as much a part of the creation process as the engineered and endeavored.

And it’s not just that it’s new—after all, every next chord and decision is new. It’s that making that specific mistake, as meaningless as it seems, was preordained to be part of the process of writing that song. Both elements—the intentional and the incidental—are equal and equally crucial.

The creative mind is open to these ideas. We’re always scanning for the next bit of input or direction. But it’s at odds with how most of us are raised. We’re brought up to get things right: the right order of the alphabet; the right way to tie your shoe; the right pronunciation of words; the right way to conduct an experiment. And these are important skills.

But at some point, we begin to conflate procedure with propriety. It’s true, certain tasks or skills have certain requirements. But we’ve imagined an inverse world where mistakes or unexpected events are failures or interruptions. I and my formerly six-year-old child and his former art teacher Ms. Y are all here to discourage this mindset. Some mistakes are mistakes. Some are Beautiful Oopses. We know about the former. We forget about the latter.

Penicillin was discovered by mistake. Sir Alexander Fleming left a petri dish of bacteria uncovered. Classic screw-up. A lab is the primary setting for right-and-wrong procedures. He got it wrong. Mold grew on the bacteria, as would be expected. But Fleming noticed it killed the bacteria—unexpected. This led to the idea of recreating this process intentionally. It turns out this was not a mistake. It was a Beautiful Oops.

The microwave oven was the result of a Beautiful Oops. So were Post-Its, Velcro, ice pops, and potato chips. So was the “I know…I know” in “Ain’t No Sunshine,” and the whistled verse in “Dock of the Bay,” and the “missing” bridge/last verse of “Wichita Lineman,” the one that ended up as a guitar solo instead because Glen Campbell didn’t know that Jimmy Webb’s song wasn’t done.

So, is that wrong turn you took on vacation that led you to the tiny slip of coastline with the best view you’ve ever seen. So, is the chain of events that led to your great love or perfect career or third child. So is your next life-affirming surprise, and the one after that.

There are no straight lines in nature. Don’t insist on them in your head, either. Some mistakes are mistakes. Some are Beautiful Oopses. Only by being open to ALL of them being Beautiful Oopses, can any of them be.

By the way, that splirp splirp on my son’s painting was not just a Beautiful Oops for him as he finished the painting. It was one for me, too, as it introduced me to a term for something crucial, which I have now used in my teaching—and —ever since. If you are a student of mine, that drop of paint on a six-year-old’s painting more than a decade ago has had an effect on your life and hopefully changed a preconception or two about how music is made and how we approach mastery, expression, intention, and enjoyment. And now it’s here in this column, too.

We all make mistakes. Whether or not we see them as referenda on our value, or surprise gifts from a complex world, is up to us.

Is there something I should offer unsolicited advice about in future columns? Shoot me a line via the contact form at joshweinstein.com and let me know.