Featured Stories

Cindy Lee Berryhill Comes Full Circle

Cindy Lee Berryhill

Cindy Lee Berryhill’s career is built on a winsome contradiction: She is a joyful exponent of the punk aesthetic that talent doesn’t matter as much as attitude, yet she has written some of the most gorgeous, hook-laden tunes to ever come out of San Diego.

But while Berryhill (who is being inducted into the San Diego Music Hall of Fame on November 8) has left a definitive mark on the local music scene, what local fans may be less aware of is the fact that she also helped shape the course of folk music in New York City back in the day. And that only came about, at least in part, because of an earlier period living in Los Angeles and being part of the punk scene there.

That is, when she wasn’t busy studying acting with Lee Strasberg.

**********************************

“I was born in Los Angeles,” she said during a recent interview. “And my dad was born in Los Angeles, too. Before that our family was from Michigan and before that, Ireland.

“My parents moved us every three or four years, so I didn’t have any long-term friends. We moved to Central and then Northern California, and my dad applied for a job in Vista in the early ’70s. We lived in Vista for three or four years, and then we moved to Ramona.”

Berryhill was just entering seventh grade when they moved to Vista and moved to Ramona ahead of her junior year of high school.

“There’s a reason I’ve lived in this apartment for 31 years: I love this feeling of stability.”

Soon after she graduated from Ramona High, she found herself in show business … in Poway.

“I was in an amateur vaudeville group. It wasn’t your classic ‘kid tries out for community theater thing,’ it was a group of waiters and waitresses and people who worked at a Mexican restaurant, and then a rodeo queen, and me, who just got out of high school. We’re all these different ages, and we were all looking for something, and we found this Mexican restaurant that had a stage in the back. We became this little troupe. We were called the Dynamic Duck; it was a dumb name.

“Most of us came with no experience at all—no education in acting—and here we are making up our own skits and making up our own songs. That’s all we lived and breathed for about two years.”

Berryhill said, though, that that experience of performing at this little theater four nights a week gave her the confidence to be on a stage in front of a room full of strangers, which has sustained her all these years as a singer.

After that troupe ended, Berryhill found herself cast as Emily in a community theater production of Our Town.

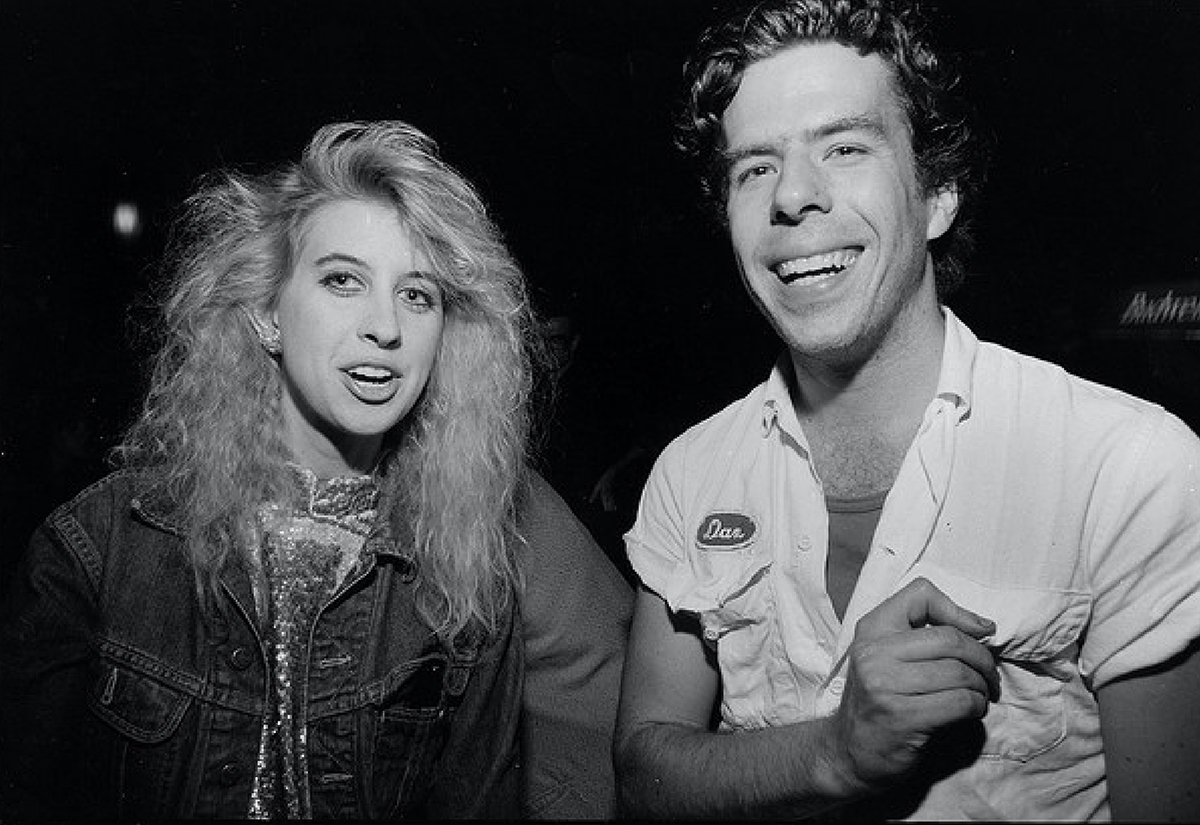

The Dynammic Duck, 1977. Julie Edens, David Ruderman, Berryhill.

“I had a good experience with that, and I decided maybe I wanted to be an actor instead of a rock star. I wanted to be the new version of what a diva was. Little did I know it was being invented at that time and was called punk rock!

“I had a friend from the vaudeville group who moved to Los Angeles, and I went up and visited him. He was caretaker of a mansion in Bel Air, and I stayed at his place and explored the city. I did a little acting workshop, and in it, this guy was so natural, I was like, ‘How do you say your lines while waving a Coke around?’

“He turned me onto method acting. He told me I needed to go to Lee Strasberg, and that’s what I did. I was 19.

“My first job was working as a singing waiter in Hollywood. One day, I waited on the Ramones. I didn’t know who they were—I still hadn’t figured out what punk rock was. They all had leather jackets on, and I’m like, ‘Are you a band?’ They pointed to their jackets, which said ‘the Ramones’ on the back.

“Within a month I went to a show, went to some more shows, got into punk rock in Los Angeles. It was kind of ironic, because punk was also happening in San Diego, but I found out about it in Los Angeles. I’m going to X, going to see Black Flag, hanging out at the Black Flag Church in Hermosa Beach, which is where The Decline of Western Civilization was later filmed.

“I had a band called the Stoopids.” Berryhill said their music was what would now be called “pop punk” today. The band came together through newspaper ads. “There was a paper in town called The Recycler. You’d put an ad in there, or you’d call about somebody’s else’s ad. I found this guitar player, who was like 22, and his girlfriend who was like 45, and she managed us.

“Then we fell apart into a million pieces. Just when we were on the advent of playing our first gig. I came back home to Ramona after essentially having a breakdown. My mental and emotional state was not in a good place.”

On the Mend in San Diego

“It took several years” for Berryhill to recover from her breakdown, she said.

“My first outings after all that was discovering Dance of the Universe, with Peter Sprague. I’d go out to those shows and I was in such bad shape I’d put my name and phone number in my pocket because I was afraid I’d forget who I was. I went to their shows, and it was inspiring. I started working on my guitar playing more.

Berryhill with Mojo Nixon. Photo by Harold Gee.

“Little by little I started to get out more. I had some friends I was playing music with. I had an older friend, who would have me play at his steakhouse gigs. There were these gigs where people would play acoustic guitar in front of the bar. I’d sometimes back him up on bass.”

She was also keeping her hand in live theater as well, via Don Victor’s improv group, where she was active in 1981. “Whoopi Goldberg was in this group, but I just missed her.”

In 1983, she was part of an acoustic duo called The Neophytes, and they got airplay on 91X with a song titled “How to Write a Hit Song.”

Berryhill also cited Rick Saxton as an important part of her development as a musician.

“For many years, he ran the open mic at Drowsy Maggie’s. It was on University Avenue, and it was THE kind of folk venue in the city of San Diego for quite a while.”

It was at an otherwise nondescript night at Drowsy Maggie’s that Berryhill came up with her sound.

“I remember watching some guys up there playing, and thinking, ‘Folk is so boring—I came out of punk rock.’ Something clicked in me: ‘Don’t play so many fancy chords and write simpler lyrics.’ I was reading Bound for Glory by Woody Guthrie, and I wrote this song, ‘Damn, I Wish I Was a Man.’ It had three chords, and it said something that women kind of felt, that they weren’t taken as seriously as their male co-workers.”

Back on the Road—and First Success

The next year, in 1985, a nice sized tax refund from the IRS led her to quit her job at Western Audio recording studio and purchase a one-month Greyhound bus pass. Inspired by Guthrie’s autobiography, she decided to see as much of the United States as possible.

My goal was to find the cool, artistic underbelly of each city. When I got to New York City, I wanted to see where Dylan had played.

“My goal was to find the cool, artistic underbelly of each city. When I got to New York City, I wanted to see where Dylan had played. Then I found my brethren, and we became the anti-folk—just because we had bad attitudes and were getting kicked out of the folk clubs. I say ‘bad attitudes’ because we had a lot of energy and didn’t take ourselves seriously. We had more of a sense of a humor, were more self-conscious than the mainstream, established folk musicians in town.

“For the people on the anti-folk scene, the important figures were Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Woody. The Beat writers were really important to us. I was reading Kerouac on the bus. Later I read Ginsberg. I kind of felt like we were going back and forth across the country like the Beats were. I wanted to get that feeling of what is America, and can we say something about that in song?”

But before she got to that point, she had to score her first show in the Big Apple.

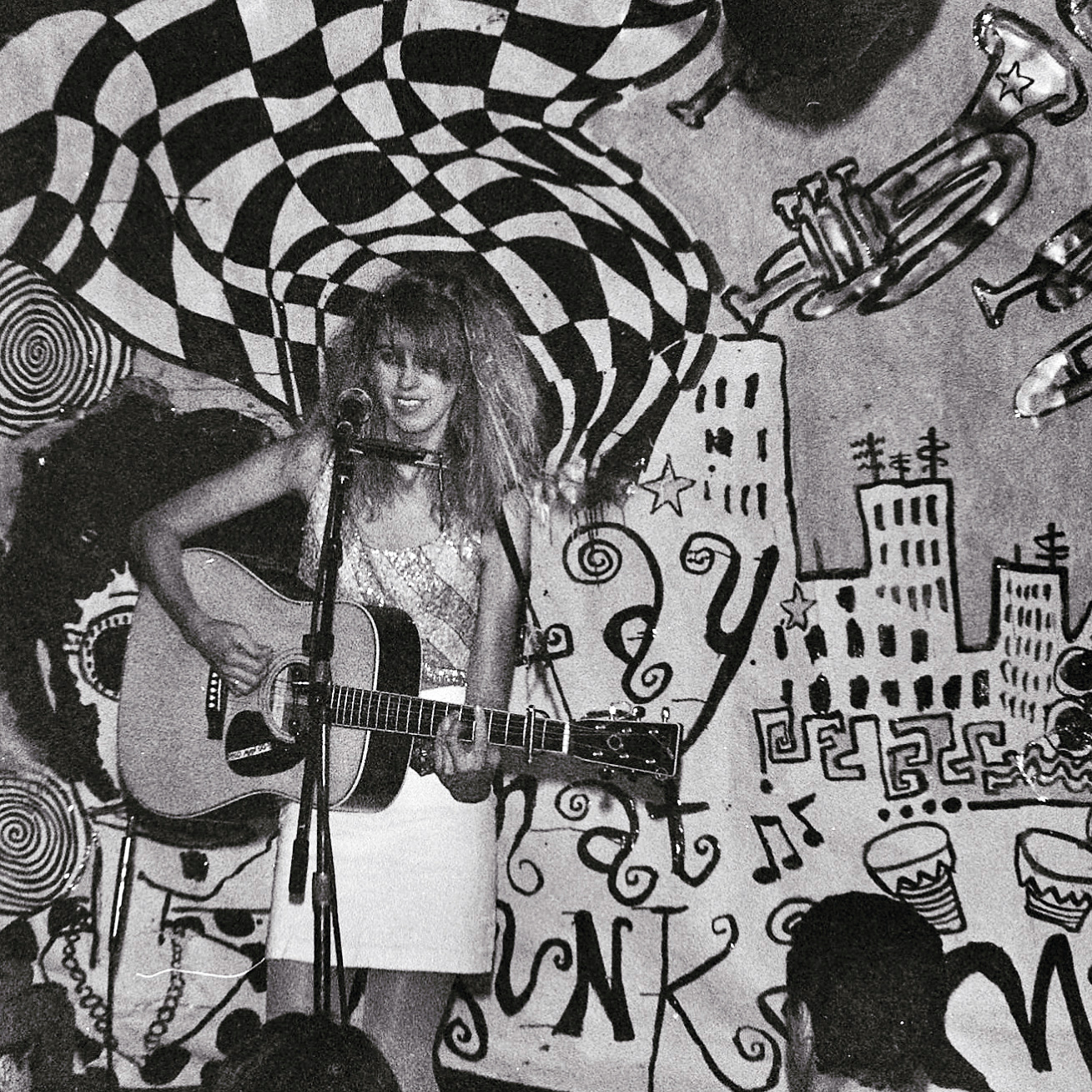

Berryhill performing at the Pyramid Club in NYC, 1985.

“Iggy Pop was at my first gig in New York City at the Pyramid Club in 1985. It was transvestite go-go dancer night, and I was on the bill!”

In the 2023 book, This Must Be the Place: Music, Community and Vanished Spaces in New York City, Jesse Rifkin devotes a whole chapter to the “anti-folk” scene that was more or less led by the singularly named Lach. According to the book, it was Berryhill herself who came up with the moniker “anti-folk,” and her getting signed to Rhino Records opened the door for fellow anti-folk singer Beck to get his record deal.

In Berryhill’s telling, it was all very organic—just a group of like-minded musicians coalescing around a couple clubs, playing their songs and finding an audience.

From 1985 to ’87, she split her time between New York City and San Diego, all the while taking side trips to Los Angeles to work on her debut, Who’s Gonna Save the World?

The release of the album, which included standout songs like the title track “Damn, I Wish I Was a Man” and “Whatever Works” led to a year-long tour “mostly headlining small venues around the country. Then I toured with Billy Bragg, the Smithereens, and X.”

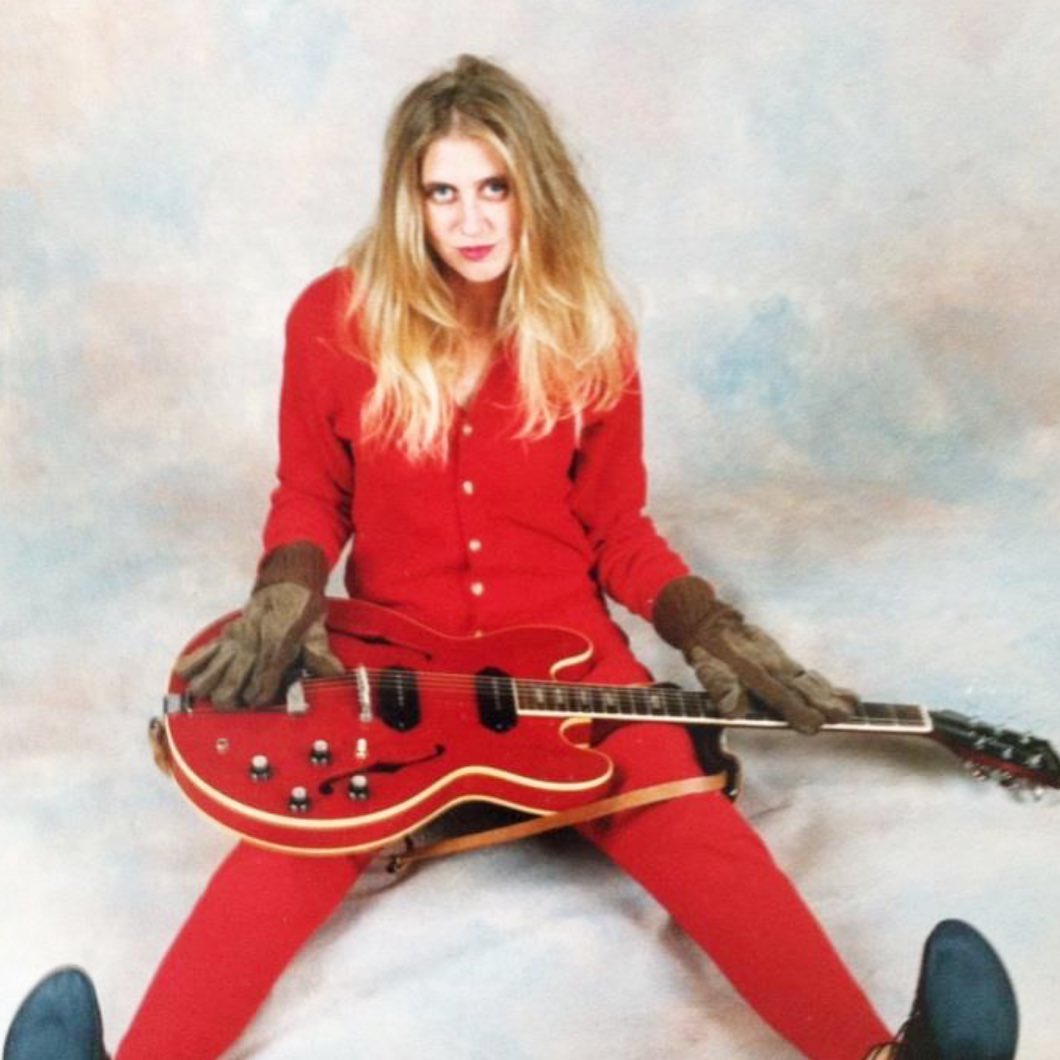

Berryhill in 1994

During this time, she also met Lenny Kaye, guitarist for the Patti Smith Group, at a benefit show for the writers of The Village Voice. “We hit it off vibe-wise right away. We made my second record, Naked Movie Star. My San Diego musicians had dropped out a year earlier and were doing other things in their lives, so this was mostly New York musicians.”

While on tour in Ireland and the United Kingdom with Irish singer Christy Moore, Berryhill had her song “Baby (Should I Have the Baby?),” which was banned by the BBC—and shortly after that, she was kicked off the tour.

Back in the States, she toured again with the Smithereens as well as the Indigo Girls and Peter Buck.

Home to Stay

Cindy Lee Berryhill and Paul Williams, 1998.

It was while on a blind date with someone else at a Bob Dylan show in Los Angeles in 1992 that Berryhill met pioneering rock journalist Paul Williams, who had founded Crawdaddy! before Rolling Stone was a thing. Soon, she and Williams were a couple.

During this time, she also recorded her third album, Garage Orchestra, released in 1994. She was working on her fourth album, Straight Outta Marysville, when Paul was in a bicycle accident and suffered a traumatic brain injury in 1995.

He seemingly recovered, and good times followed—with 1996 seeing Straight Outta Marysville released, their wedding the next year, and the arrival of their son in 2001.

Unknown to them at the time, he was suffering ongoing brain damage from the accident. As dementia began to set in, Berryhill coped the best way she knew how: she recorded the album, Beloved Stranger, about what her family was going through.

In March 2013, Paul passed away from the effects of the injures from that 1995 accident. She is now conservator of his estate—and, more important, his legacy.

Despite his towering role in rock journalism, treating the then new form as seriously as jazz and classical critics treated their subjects, Berryhill said Williams never really got his due—not even as one of the leading authorities on Dylan’s career. “He was always on small, independent publishers and, if he was fortunate, he’d get a couple thousand dollars of advance. His last Dylan book did pretty well. In our whole time together, from 1992 to 2013, there was one time he a got a check for $30,000 and I remember contacting the publishing house and asking, ‘Can you check and make sure that’s right?’ That meant we could pay our health insurance for a year!

“I did get his archive placed three years ago at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Paul was originally from Boston, so that makes sense. They’re doing a great job taking care of it there. Somebody recently bought the film rights to Paul’s book Only Apparently Real, which is conversations with Philip K. Dick. It was nice that someone was interested in one of his books.

“Every so often I get a check for $150 for one of his books. He set them up on a print on-demand service. You can buy his books through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or any of the big bookstores.”

Looking Ahead

Her most recent album, The Adventurist, came out in 2017, but Berryhill said she’s moving forward with the next recording.

“I have a few songs that have come up in the last few years—it hasn’t been a full song cycle, but I have so many songs that haven’t made it onto albums, so it was time for them to be properly recorded.”

Berryhill headlining at McCabes in April of this year. With John Kruth, Willie Aron, Stephen Kalinich, Jeff Greenstein, Paulina Porizkova.

Berryhill explained that her song-writing process is episodic. “It starts with inspiration. It’s also a thing where I have to sort of have some kind of notepad around me. Something will come come and I have to write it down. I write in song cycles—it’s like a farmer tending the earth. Sometimes it doesn’t give forth. I have to let that land go fallow for a while, and then a few years later songs are just popping up all over the place, and that becomes an album.

“Renata Bratt, we connected after she was at UCSD, has been up in Santa Cruz for the last 20 years. So she’s a part of this. Willie Aron, from the L.A. scene, was in a band called the Balancing Act, and he has played with almost everybody: Peter Case, Leonard Cohen, etc. And the other guy is John Kruth, from New York City, who can play almost any instrument you can think of. The three of us did a couple of shows together in Venice after COVID, and we just really had a nice connection. So in the last year, we’ve done some shows together, and I’m like, ‘Damn, this is a great vibe.’

“Now we’re going to go into the studio the day after the election. Right now, I’m just going into the studio for two days. I’m paying for it myself, and then I’m hoping to do a fundraiser so I can afford for us to do more stuff. I’m trying to figure out how I want to go with that.

“We’re also playing in San Diego November 3 at a curated house concert series called Palo Verde House Concerts, hosted by Michael Rennie.”

Berryhill said that people assume musicians make money off touring; she said while that may be true for the big-name acts, it’s more of a struggle for most musicians she knows, .

“Playing my songs is fabulous—but honestly, playing my songs is like going on vacation where I’m going to spend money and have a good time.”

Cindy Lee with her son, Alexander.

So, for the last 20 years, she’s taught music full-time. “I needed to find a way to make a living! I teach four days a week, and I’m my own boss and it works out really well. I teach guitar, songwriting, and ukelele. I have students who started with me in second or third grade, and now they’re in college and stay in touch; that’s really nice.”

In addition to working on the new album, and a full teaching schedule, Berryhill is also working on her first novel. “It’s a fictionalized account of my time on the Los Angeles punk rock scene and hanging out at the Black Flag Church, while at the same time going to Lee Strasberg’s school. I’ve been writing for a couple years now. I passed 300 pages, and I’m winding it down—all the bad stuff is happening now! [laughs] People are dying and falling apart.

“It’s been a joy to write, and I really have a good time writing. I’m also part of a writer’s workshop, and I get some laughs and people like what they’re hearing. I also have a couple friends who are well-known writers, and they’ve offered to give it a read.

“It was one of the darkest times of my life. I didn’t know if I’d ever get out, and when I did, I thought I’d never go back. But now, looking back and fictionalizing it has been great. You can see humor even in your darkest hours.”

******************************

Cindy Lee Berryhill at Palo Verde House Concerts on Sunday, November 3, Rolando neighborhood, 3pm. RSVP: michaelbookstalent@gmail.com / 619-871-7400

Berryhill will also be honored at the San Diego Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Friday, November 8, 7pm, located at Vision: A Center for Spiritual Living, 4780 Mission Gorge Place, Ste. H.