Featured Stories

The Elegant Touch of Mike Wofford

Whenever I go back to my hometown of Cincinnati and look up my friend, pianist Steve Schmidt, he inevitably asks me, “What’s the name of that great piano player in San Diego?”

After I mentally scroll through the region’s roster of distinguished keyboard artists, I inevitably reply, “Oh, are you talking about Mike Wofford?”

“Yeah, that’s the cat. Wonderful player,” he would respond. And that’s saying a lot in a town that has had numerous great pianists over the years, including ECM artist and multiple Grammy award nominee Fred Hersch.

Born and bred in San Diego and a graduate of Point Loma High School, Wofford described himself in a 1980 interview as a largely self-taught player, which is highly unusual among pianists.

Wofford was recently laid to rest last month at the age of 87. He will be missed. Music journalist, the late Robert Bush, wrote a comprehensive article on the life and career of Wofford in a 2023 edition of the San Diego Troubadour. (Michael J. Williams)

Mike Wofford. Photo by Zach Karabashliev.

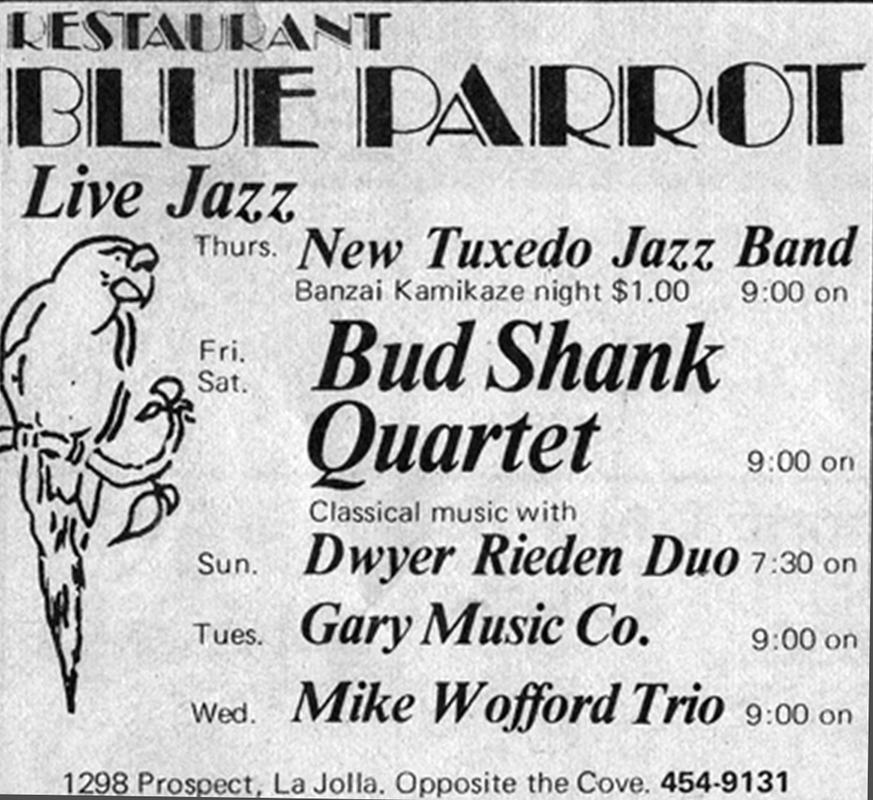

Mike Wofford’s curriculum vitae reads like a who’s who of modern West Coast jazz, dating back to the late 1950s and continuing to this day. I’m a student of jazz history, and virtually every significant player I’ve ever read about has some connection to him personally. Names like Shorty Rogers (trumpet), Shelly Manne (drums), Howard Rumsey (bass), Chet Baker (trumpet), Stan Getz (saxophone), Art Pepper (saxophone), and Gary Peacock (bass) represent the tip of the iceberg.

He grew up in San Diego, mostly self-taught, and he honed his skills around town with local heavyweights like Daniel Jackson, Gary Lefebvre, Don Sleet, and John Guerin. He matriculated often to L.A. for live gigs, and he penetrated the studio system in the 1960s through an association with Oliver Nelson, working on TV film scoring, and pop-music sessions with artists like the Jackson Five, Cher, and John Lennon, to name but a few.

Wofford in 1988, with Bob Magnusson & Jim Plank. Photo by Michael Oletta.

He’s led a whole independent career in terms of working with vocalists, and once again his pedigree is unassailable: in 1979 and 1983, he toured the world with Sarah Vaughan as conductor and pianist, a position he also held with Ella Fitzgerald from 1989 to 1993. Before all of that, he toured with June Christy.

And it wasn’t just the West Coast jazz cats who have benefited from the master touch of Mr. Wofford. Saxophonists like Sonny Stitt, Phil Woods, James Moody, and Lee Konitz all hired him, as did vibraphonist Gary Burton and drummer Matt Wilson.

He’s performed or recorded with Quincy Jones, John Clayton, Jeff Hamilton, and Ray Brown. He’s also worked with several icons from the avant-garde including saxophonists Oliver Lake and Vinny Golia.

I write all of this with the appropriate sense of awe such a list should engender—but also to relate that Mike never comes off as the icon he clearly is. He’s one of the most grounded and low-key people I’ve ever met and also one of the most intelligent and funny cats I’ve ever hung out with.

Above all, he’s got that master’s touch whenever he sits down at the acoustic piano. He can make me melt just in the way that he voices a chord and how he shifts from that chord to the next—it’s as close to magic—or at least alchemy—that one is likely to experience in this mortal coil.

Speaking with someone of such depth is always a profound opportunity, and I’ve also been fortunate enough to gather some short testimonials from musicians whom he admires.

Mike Wofford is not only a gem of a pianist but also a consummate human being. The beautiful music that comes from his heart and mind, through his hands, is always soulful and real. His immaculate touch, his sound and his wide range of styles are all intrinsically his own, but of course you can hear the influence of other great pianists in his playing. One of the things I really love about Mike’s aesthetic is his ability to navigate most any style of jazz. Just when you think you’ve heard it all, he’ll surprise you! That goes for his compositional style as well—each song he writes has its own “gravity” that pulls you in, from beginning to end. Looking back at his work with Shelly Manne, his own trio, and so many other luminaries, I get a sense that Mike has (and will) always be searching for something to pull from the piano. His Strawberry Wine album is a perfect example of his style and range. Highly recommended!

JOSH NELSON, pianist, composer

Mike was still in grammar school when music entered his consciousness. “I was always interested in classical music before I knew about jazz, but my mother had some early jazz acetates, and I was really fascinated by them—especially [cornetist] Bix Beiderbecke. I thought Bix was incredible and I still do. Later, I discovered some great live jazz on the radio. It was strictly radio in those days. I heard the great Art Tatum on a program called Piano Playhouse on Saturday morning and also Teddy Wilson and other heavy players of the time. My mother wanted me to pick up the piano, so she rented one for our living room. She had been a professional singer before she got married.” Mike was about six when he started playing, and soon he was taking lessons at a local music store. “Bill Franks was his name; he was a wonderful guy. He was a Teddy Wilson fan. Instead of the usual classical training and scales (which most kids hate), he taught by breaking down popular songs of the day and figuring out what the chord changes were. He was very patient, and he always encouraged me. I would try to figure out “Body and Soul,” and he would make suggestions to help me get it right. That was about the extent of my formal piano lessons, but I’ll always remember Bill Franks as being the one who really got me inside piano music.”

San Diego had a pretty fertile music scene in the late 1950s, and Mike soon found himself jamming with (future drum superstar) John Guerin, (trumpeter) Don Sleet, and (tenor saxophone giant) Daniel Jackson. The young San Diego crew would frequently head north to Los Angeles. “The proximity between the cities was so small, by the time I could legally drive we’d head up there, primarily to the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. Even though we were underage they’d let us in, we’d drink Cokes or something. They had all-day sessions on Sunday, and we’d be there just taking it all in.”

After a few years, record producer Albert Marx took notice of Mike and signed his trio with John Guerin on drums and bassist John Doling to Epic Records for Wofford’s debut album Strawberry Wine back in 1964. Marx would go on to found Discovery Records. Almost 60 years later, Wofford is circumspect about the record. “I listen to it every once in a while. The thing that surprises me is I sounded better than I thought I did. It’s not world class or anything, but it’s better than I remember.”

Ella Fitzgerald

Sarah Vaughan

One of the true tests of a piano player lies in the way they accompany a vocalist, and when it comes down to that metric, Wofford is very good indeed. It wasn’t by accident that some of the world’s most acclaimed singers chose him as their accompanist. “I don’t remember exactly, but someone in L.A. knew that Sarah was looking for a new pianist, and this person recommended me. I got a phone call from her, and I drove up to Hollywood where she was living and met up with her. We seemed to hit it off really well, and I ended up working with her for a couple of years, both on tour and back in L.A.” Scoring a gig with Sarah Vaughan represents a high degree of serendipity, but when Ella Fitzgerald came calling later, Wofford moved into another level that cannot be reduced to good fortune, more like the ultimate example of meritocracy. “Norman Granz, the concert entrepreneur, was handling her, and he called me to ask if I’d be interested in working with her, so I hopped into my car and drove up to L.A. She had a beautiful house in Hollywood, and we hit it off right away. She was very easy to work with. She never really complained or got upset about anything. She was very even tempered as was Sarah. People who are that great typically tend to be the kindest and most sensitive. The ones that yell at you and make you feel bad aren’t necessarily the most talented. I should also include June Christy in that pantheon of great singers. I worked with her for a year and a half back in the early 1960s, and she was just marvelous.”

I had to ask what makes for a great accompanist, since Mike would certainly have the answer. “I think the primary formula is ‘less is more.’ When in doubt, play less. A lot of times the accompanist gets a little carried away and plays way more than is necessary. For the most part, especially as I gained experience, I tried to eliminate as much stuff behind a singer and just concentrate on helping them rather than showing off or trying to play everything I ever knew. Accompanying is primarily being first sensitive to the material. It’s very important to understand the music and the lyrics as well.”

Mike Wofford is most certainly a towering musical figure to anyone who hears him at the piano, on record or in person. I first met Mike back in 2003 at the inaugural UCSD Jazz Camp and I have been in awe of his musicianship ever since. To hear him at the piano is to hear a musician with a deep sense of integrity and sincerity for each note that is played. Also, having shared the stage with Mike as a piano duo, it has been an immense thrill to exchange musical ideas with such a master musician in front of an audience. He is truly a pianist and composer of the highest order.

JOSHUA WHITE, pianist, composer

I was surprised to learn that Wofford does not necessarily practice obsessively. “The only time I really do it is if I’m trying to sort out a particular piece of music. That’s when I’ll sit down to make sure that I’m playing and learning it correctly, but otherwise I don’t get up in the morning and think ‘oh boy, I can’t wait to practice.’ I’ve just never been that way. I’m not bragging about that, I’m sure I should have practiced more than I have, but at this point in life, I just do the best I can with what I have.”

I interviewed Wofford a few years back for my podcast about the iconic Miles Davis album Kind of Blue, which featured the late pianist Bill Evans on four of the five compositions. This interview represented a chance to follow up on his ideas on Evans.

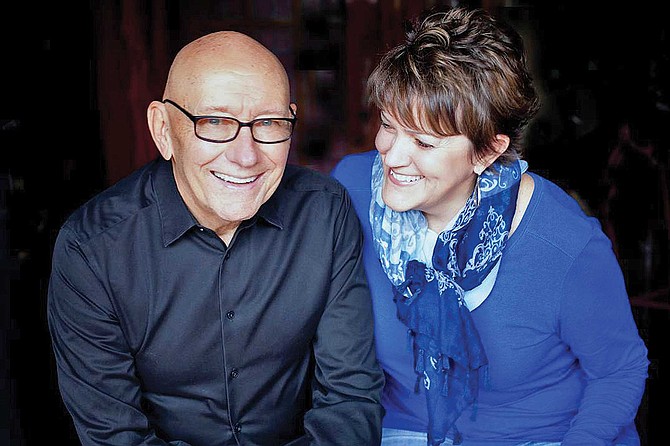

Wofford with his wife, flutist Holly Hofmann.

“I actually knew Bill slightly before he passed. I didn’t get to know him well, but I did spend a little time around him, and he was a wonderful, wonderful person. And of course, he was a remarkable pianist. He had his own thing, which is really important. I mean, look at Art Tatum or Errol Garner—and you could go on and on—they all had their own thing. Bill brought a whole new sound of jazz piano to the forefront. When his first records came out, everyone fell in love with his playing. He was remarkable and it was so fresh; it was very unusual. And it had his trademark all over it from day one, and I very quicky got it. I realized I could understand his playing immediately if I happened to turn on the radio—I knew it was him in just a few notes. So that’s a pretty remarkable thing. Not everyone can say that about their playing—that it’s personal and unusual and instantly recognizable. He was an excellent pianist. I remember being around him at a friend’s house in L.A. where there was a piano. He sat down and played some Rachmaninoff, I think, or one of the heavy piano composers. He was classically trained but his jazz playing and popular playing had no stiffness at all. It was very fluent, and it knocked everybody out. I think every piano player in the United States was trying to sound like Bill Evans at one time. You almost couldn’t help but try to imitate him. And then I quickly learned that’s not the way to go. I mean, it’s good to learn from anyone, but you don’t want to just be aping somebody’s playing, you know?”

Another monster musician that Wofford played with in the 1960s L.A. scene was the bassist Gary Peacock. “I just loved Gary. He was a wonderful fellow and a marvelous bassist. I think I met him just before he joined the Bill Evans Trio, and we did some playing around L.A. He already had tremendous credentials. He played with a lot of great players before Bill Evans. He was a fantastic soloist and very knowledgeable about harmony. He was everything you could want from a bass player in a jazz setting. I really enjoyed working with him and we even did some recording together.”

Back in the 1960s, Mike got hooked up with the vibrant L.A. studio scene, and he eventually worked with television and movie soundtracks with a slew of pop-music artists. What did he work on? How about M.A.S.H.? Or a little movie called The Godfather? Remember The Merv Griffin Show? Or You’ve Got Mail? He also played on a ton of record dates with people like Joan Baez, the Jackson Five, and John Lennon. “I was just a sideman. When the phone would ring, I would show up. I got a lot of work through [mega-arranger and saxophonist] Oliver Nelson. He called me and we did a lot of recording together.” I asked Mike if he had any memories of some of those pop-music dates. “The phone would ring. I don’t remember a lot of the circumstances of why they called me, but I did end up working with Cher when I was backing her in a band on her TV show. Later on, I did other things on that CBS show. She was a wonderful singer, wonderfully gifted and very, very shy. I never had much interaction with her, but she was really talented. Working with John Lennon is kind of a distant memory as far as the details. But I really enjoyed working with him. This was several years after the Beatles (1975) broke up, so he was strictly working as a single. I was on a couple of things with him, and he was great, really super to work with.”

Wofford today. Photo by Michael Oletta.

Another mark of a well-rounded pianist is the ability to play solo, and it turns out that Mike nearly set a record in that regard. For many years, he played at the University Club a swanky gig located at the top floor of Symphony Hall. “That was a wonderful job. It paid really well, and it was very close to home. I just enjoyed every minute of it. I can honestly say, and I still can’t quite believe it looking back, that that gig lasted 18 years. But it just flew by, it seems. I started out working there with a trio, but shortly thereafter, it became a solo piano gig. I think that was the second-longest running gig I know of next to Bobby Short’s NYC engagement at the Café Carlyle, which went for 35 years.”

Currently, Mike has started a new solo residency at the Manhattan Room at the Empress Hotel in La Jolla, which has been happening for a few months. For many years, Mike Wofford and his wife, [flutist and impresaria] Holly Hofmann, have been one of San Diego’s ultimate “power couples” on the arts scene. “Well, she’s been just wonderful for me, of course our musical connection has been tremendous, and that’s a really big part of our life and relationship. We’ve had a wonderful time working together in all sorts of circumstances. She’s an amazing entrepreneur as far as putting things together, making things happen, getting things organized for a music series. She’s known worldwide now as a flutist, but she’s also a really good businesswoman and she’s created a lot of wonderful situations for us to play together.”

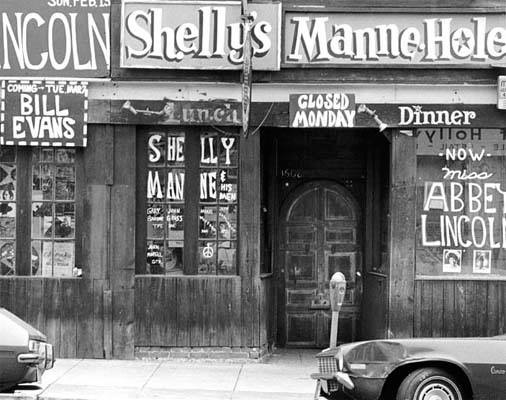

I just love playing with Mike. He can pull his sound back into some hidden recesses, and he brings the history of the music with him in every note that he plays. You have to be on the top of your game to really make cognizant music with him. He has a depth of emotional knowledge and experience that comes from his presence on the planet and what he has experienced in life. I first saw him playing with Shelly Manne at the Manne Hole when I visited California in 1971. Shelly was into more freeform music, based on what Miles was doing or had done. Mike was on fire in the keyboard role, playing more Fender Rhodes than acoustic piano. When he first played with Bert Turetzky, Mike brought all of this experimentation forward into a different context; I was floored by how open he was. Then he asked to do some duo playing and I was in heaven. I could place the sound into an amazing bedding of harmonic clouds or run off on some linear trip without ever having to worry about being supported. Just glorious playing with him. Mike is a very underrated pianist especially in the history and lineage of the jazz tradition, overlooked I think because of his association with the West Coast.

VINNY GOLIA, composer, multi-instrumentalist

Shelly’s Manne Hole back in the day.

I’ve always been curious as to how Wofford, a guy with all of the mainstream credibility anyone could ever want has been able to keep his ears so remarkably open. Very few cats who played with Stan Getz or Chet Baker have been so enthusiastic about the music of Ornette Coleman, for instance. “I don’t have any clear-cut explanation for some of the widely different situations I’ve explored. At the time I probably didn’t even realize I was doing it. I remember when Ornette Coleman came on the scene it was a huge controversy in the jazz world. I mean he just turned things around completely with his first recordings and appearances with his own band. And also, Cecil Taylor. I always really admired what Cecil was doing, but a lot of musicians couldn’t stand him. They really couldn’t hear what he was doing. I thought his approach to jazz piano was absolutely unique, and I thought it was wonderful. I got what Cecil and Ornette were doing right from the beginning. I had their earliest recordings and I loved what they were into; it was so different and vital. I kind of brushed elbows with Ornette at Shelly’s Manne Hole once or twice when he was playing there, and I was also working on the off nights. So, I was around him a little bit. I wish I’d had the opportunity for a real conversation. But at least I was in the same room, and I really loved his stuff.”

To close out our interview, I asked Mike how he felt about the future of this music we call jazz. “It goes through a lot of changes. Some for the better and some for the worse. Change is normal, that’s normal in any process. People are going to try different things and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. I just try to keep my ears open to anything that is substantial and has value. The only time I’m disappointed is if something is poorly performed. But I still keep an open mind and listen to young players and the older players as well. It’s a real journey, I think, for everyone. If you’re serious about the music, you want to stay open for everything. I remember when Cecil Taylor first hit the scene some musicians that I knew just hated it. But I loved it immediately. People thought there was something wrong with me, but I think you should stay open and be ready to learn from everybody.”

What does Mike bring to the music that is so special? His generosity: he always provides that and an uplifting spirit. He always provides rhythmic energy. He always provides harmonic richness. As a pianist he provides a history of the piano in jazz, from Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Bud Powell, and Thelonious Monk forward. He has a very personal sound, no matter what piano is being played. His knowledge of the standards of both Jazz and the Great American Songbook is vast and his sensitivity with a vocalist is well known.

JIM PLANK, drummer, percussionist

In closing, the opportunity to speak with someone so inherently connected with jazz history is a profound honor. I could speak with Mike for days because every answer he provides makes me think of another three questions to ask (at least.) He’s so incredibly humble for a man of such stellar contributions to the artform. Talking with him is always a cause for celebration.