CD Reviews

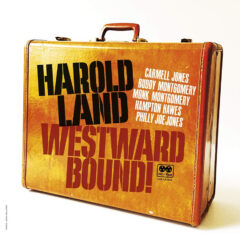

HAROLD LAND: Westward Bound!

San Diego County’s three greatest exports may be Ted Williams, Harold Land, and avocados.

While most folks are familiar with the baseball Hall of Famer who crafted greatness with the Boston Red Sox, the equally gifted tenor saxophonist, Land too often is overlooked, even here in his hometown.

Land was born in Houston, but his family moved to San Diego when he was six years old.

By high school, he was already gigging with Fro Brigham’s band—and when trumpeter Brigham managed to land an L.A. recording date with Savoy Records in 1949, he put the 21-year-old Land’s name down as leader. Five years later, Land was playing in the legendary Clifford Brown-Max Roach Quintet.

He only stayed a year and a half before he came back to take care of his pregnant wife. When he left, he was replaced by a then-unknown Sonny Rollins, who turned that gig into widespread fame.

Land moved his base of operations from San Diego to L.A. in ’56—and never did move back to town. But he had a nice career, leading a variety of outfits as well as gigging and recording with folks like Wes Montgomery, Thelonious Monk, Bud Shank, and Red Mitchell. He passed away in 2001 in Los Angeles.

But staying on the West Coast likely cost him the kind of recognition his fat tone and technical brilliance would have earned him in New York—he never did become as well-known as Rollins did after replacing him.

A set of long-forgotten live recordings made at The Penthouse nightclub in Seattle from 1962 to ’65 has now been released by Reel to Real Records, and while the recording quality is noticeably less than studio, the playing here is exuberant and confident, a portrait of an artist in his creative prime.

The first three tracks are from December 1962, with Land fronting a quintet that includes Carmell Jones on trumpet, Buddy Montgomery on piano, Monk Montgomery on bass, and drummer Jimmy Lovelace. Having two-thirds of the Montgomery Brothers (only guitarist Wes is not present) in the rhythm section provides this set a loose, swinging familiarity. The 24-minute set doesn’t include any terribly well-known songs—a search of Land’s discography shows this is the only known recording of him performing his own composition, “Vendetta,” a fast-paced bop romp with Land blowing through the theme and then vamping off it before handing it over to Jones.

“Beepdurple” is from Jones’ pen, although he wouldn’t record it under his own name for three more years on his Jay Hawk Talk LP. A play on the title of the 1938 hit “Deep Purple” by Peter DeRose, “Beepdurple” is a mid-tempo piece that opens with Jones and Land on a dual lead with Lovelace driving them along. Land takes the second extended solo, riffing of what Jones did, both in absolutely gorgeous tone.

The 1962 set concludes with a medley of “Happily Dancing” and “Deep Harmonies Falling,” both written by Land—and both apparently recorded for the first time here. The opener is a pleasant if not terribly memorable melody but gets a nice dual-lead treatment by Land and Jones. Buddy Montgomery gets a lengthy solo toward the end, showcasing his percussive yet flowing style on piano.

The second set was recorded on September 17, 1964, in a quartet setting. It comprises just two tracks, but clocks in at about 23 minutes. Here, Hampton Hawes is on piano and Mel Lee on drums—Monk Montgomery remains on bass.

The band opens with a relaxed take of the Rodgers & Hart ballad “My Romance,” written for the 1935 musical Jumbo. Hawes kicks it off with a sparkling intro, accompanied only by Montgomery before Land and Lee join in. As the song progresses, the tempo gradually increases, until the band has turned the sentimental love song into an up-tempo bop number: And then, on a switch, Hawes slows it back down with an absolutely delightful lead passage, again accompanied by Montgomery for a bit until Lee joins back in. Montgomery follows with his own remarkably spry solo on his double bass, before Land and Lee trade solos until a rousing close.

Another previously unreleased Hawes original, “Triplin’ the Groove,” finishes this 1964 set. An aggressive opening by Land is followed by his own extended solo before Hawes just about steals the show with an absolutely inspired reworking of the theme. Montgomery provides another soulful solo on bass.

The final four tracks are from August 5, 1965, with Land and Montgomery joined by John Houston on piano and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Here they open with the chestnut “Autumn Leaves,” Houston comping the harmony on the low end of the piano before Land jumps in on the well-known theme. His tone is fat and rich, his playing nimble and sure-footed. Houston’s solo is linear, frequently citing the melodic motif without ever getting too far from it. Montgomery’s bass solo is as wondrous as the ones heard on the previous sessions 12 and 19 months earlier.

Houston opens the Anthony Newley-Leslie Bricusse song “Who Can I Turn To?” (which had only been written a year before, but was climbing the charts via Tony Bennett’s recording when this session was captured) in a slow, ballad mode. Land takes over the lead but keeps the tempo pretty near where Bennett had laid it out in his hit version.

The quartet gets back into a hard bop vein on Philly Joe Jones’ “Beau-Ty,” and Jones takes an early ownership stake with a powerful, driving rhythm that at times overpowers Land and Houston. The closing tune, Dizzy Gillespie’s “Blue ‘n’ Boogie,” opens with a stellar drum solo by Jones. Land then jumps in alongside Jones on a shared lead, with Houston and Montgomery comping behind. Land then steps back and lets Montgomery take a bowed solo on his double bass, while Land blows bass lines on his tenor sax. Jones then strides back to the sonic foreground on drums again before the band offers a quick outro.

The packaging is top-notch. A 24-page booklet includes a lengthy biograhy by Michael Cuscuna, detailed session info, background interviews with Sonny Rollins and Joe Lovano, and an essay from Eric Reed about the pianists heard here.

By covering a three-year stretch, with three different lineups, this collection captures a representative snapshot of Land’s playing during that time span. The results show that while Land’s fame may have been fleeting, the caliber of his playing was still on the rise.