SUE'S SPOTLIGHT: Women in Blues and Jazz

Women in Blues and Jazz: Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Mary Osbourne, Barbara Lynn

This month marks the second year of my engagement as a columnist for the San Diego Troubadour! I have been grateful to share just some of the stories of outstanding women in jazz and blues, and I look forward to this next year. Since I am a piano player, and women have traditionally been encouraged to at least play that instrument, many of the women I’ve written about, were excellent piano players. In this issue, I am exploring some of jazz and blues’ excellent female guitar players.

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE, 1915-1973

My whole career has been one long Sister Rosetta Tharpe impersonation. — Chuck Berry

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was “the Mt. Rushmore of the Architects of Rock ‘n’ Roll” — Beverley Knight, queen of British soul music, actress who portrayed Rosetta in 2025, in the play called Marie and Rosetta.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Rosetta’s dazzling guitar playing, which featured a finger-picking style unusual at the time, influenced Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Tina Turner, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Etta James, Bonnie Raitt, Ruth Brown, and more. She was among the first of the recording artists to use heavy distortion on her electric guitar, opening the way to the rise of electric blues. Her 1945 hit, “Strange Things Happening,” a humorous jab at religious hypocrisy, may well be the first rock ‘n’ roll song. Hear her play it in the video, accompanied by Sammy Price, Decca Records’ house boogie woogie piano player.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe started her career at the age of six with her mother, Mrs. Katie Atkins Nubin, who was an evangelist and musician in the Church of God in Christ. In the 1920s, her mother moved the family from Arkansas to Chicago, continuing their work in the church. Eventually, they became traveling musicians on the church circuit. Here, Rosetta was quickly spotted as unusual, gifted, and special. To Pentecostals, a gift was something to be used and used well, which meant the way the Lord intended. Eventually, she became the first great recording star of gospel music, incorporating Delta blues, New Orleans jazz, and gospel music into what would become her signature sound. People began attending her church, just to hear her play. Although her distinctive voice and unconventional style attracted fans, it was still the mid ’30s. Female guitarists were rare, and even more so was a musician who pursued both religious and secular themes, a fact that alarmed the gospel community. Rosetta attempted to inhabit an in-between place where the worlds of religion and popular music intersect. That takes courage and lots of chutzpah, which she had plenty of. When she was at the top of her game, no one could touch her charisma or jaw dropping talent.

In 1938, Rosetta recorded four gospel tunes with Decca, which were overnight hits on the Harlem Hit Parade. The next year found her invited to play at the Cotton Club with the Lucky Millinder Orchestra. Millinder was a respected band leader and had a talent for shaping a group of talented musicians into a smooth-playing swing band, a much under-appreciated talent. She was hired to be the featured female singer, which led to more high-profile gigs, at the Savoy Ballroom, Cafe Society, John Hammond’s Carnegie Hall concerts, and the Apollo Theatre. Needless to say, the church was very upset with her playing and recording secular music, like “Tall Skinny Papa” and “4 or 5 Times,” playing guitar with jazz and blues musicians and scantily dressed dancers. After two years with Millinder, she quit to pursue a solo career. She decided to go back to her gospel roots. Eventually, she teamed up with piano player and gospel singer Marie Knight.

Rosetta was uncomfortable out of her gospel roots and wanted more control over her material choices. She heard Marie Knight singing with Mahalia Jackson, in 1946, and offered her a job right there. They became a popular act, working, touring, and recording for about five years, then, off and on in the ’50s. “Up Above My Head,” recorded in 1947, became Marie and Rosetta’s signature song. They had wonderful chemistry on stage, with Marie’s alto complementing Rosetta’s soprano voice, playing off each other. It was sometime in the early years of their collaboration that word began to get around the gospel scene—that they were more than “just friends.” Although Rosetta sang about the wages of sinful living, she pursued relationships, primarily with men (three marriages), but occasionally with women, including Marie Knight. She wore pants before they were the norm for women and swore like a sailor. A female gospel singer, playing guitar in a spangled evening dress, was unique in the early ’50s and probably still is. Even when playing her gospel repertoire, she stuck out as a loud woman with a big personality. The gospel professionals tended to look the other way, if one didn’t flaunt it too much. No one wanted to ruin another person’s career and livelihood. Marie experienced a horrible tragedy in 1950, when a fire killed her two children and mother. It ended their duo and relationship as lovers, but they remained good friends until Rosetta died. In 2016, a play celebrating their musical relationship, Marie and Rosetta, was first performed in New York City. It has been performed around several cities in the U.S. (including San Diego, at the Cygnet Theatre) and continues to be performed in England, scheduled for February 2026, with British actress and soul singer Beverly Knight.

In 1950, Sister Rosetta Tharpe staged the biggest concert of her life: her wedding and third marriage to Russell Morrison. It took place in Griffith Stadium in Washington D.C., with at least 25,000 people in attendance. Rosetta, in a white dress at a cost that rivalled that of a car in those days, became the first female stadium rocker! Several acts joined her, including Marie Knight, and her mother, Katie Bell Nubin. The idea of combining her wedding with a performance appealed to Rosetta’s sense of entertaining. She recognized life itself as something of a performance, where the fun lay as much in breaking the rules as adhering to them. She outsold the Washington Senators, in their own stadium. It was called the world’s greatest spiritual concert.

Rosetta’s career continued and got a big boost from the post-World War II blues revival in Europe. Young white males were beginning to take the rock ‘n’ roll audiences away from the scene Rosetta was in, so the timing was perfect. She was welcomed with open arms and began to acquire fans like Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, Brian Jones, and Ginger Baker. Although her career slowed in the ’60s, she was still sharing bills and performing with most big stars—of different genres—including Red Foley, a country and gospel singer. She began to feel poorly in 1970 and died of a stroke, brought on by diabetes, in 1973, at the age of 58. She had essentially been on the road practically her whole life.

Although she was a household name in the ’30s-’40s, she was forgotten for the most part until the last few years, but she is being honored by many tributes in the 1990s and 2000s. Her pioneering has finally been recognized. She was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 2017. She was a musician and a flamboyant black rocker before rock ‘n’ roll, who broke every categorical norm with her style. And, as a black, queer loving divorcee, managed to live her life to the fullest, despite restrictions from her religious community and the racism and misogyny of the time.

MARY OSBORNE, 1921-1992

Mary Osbourne in the 1940s.

Jazz guitar pioneer Mary Osborne was the only female jazz guitarist to make an impact on jazz in the 1940s and ’50s according to Jim Carlton in Vintage Guitar Magazine, 2011. Although Mary herself said, “There’s nothing unusual about women being musicians. In the ’40s, when I came to NYC, Billie Rogers played trumpet in Woody Herman’s band, and Dardanelle and I were just musicians. Nobody ever wrote about a girl guitar player. I got my jobs because I played and sang.”

Mary Osborne was from a musical family in North Dakota. The 10th of 11 children; everyone in the family played, and her father’s barber shop was the meeting place for the town’s musicians. Mary began with the ukulele at four, then went on to play piano, violin, and banjo. At nine, she started playing guitar. By the time she was a teenager, she had her own radio show, also played bass, and first heard Charlie Christian play the electric guitar. Mary became a student of Christian’s, who was known as the first jazz musician to popularize the electric guitar. He is probably best known for his stint with Benny Goodman. After meeting him, she immediately went out and bought an electric guitar and had a friend build her an amp. Occasionally, Christian allowed her to sit in with his band, instructing her as they went along. She was developing her jazz chops.

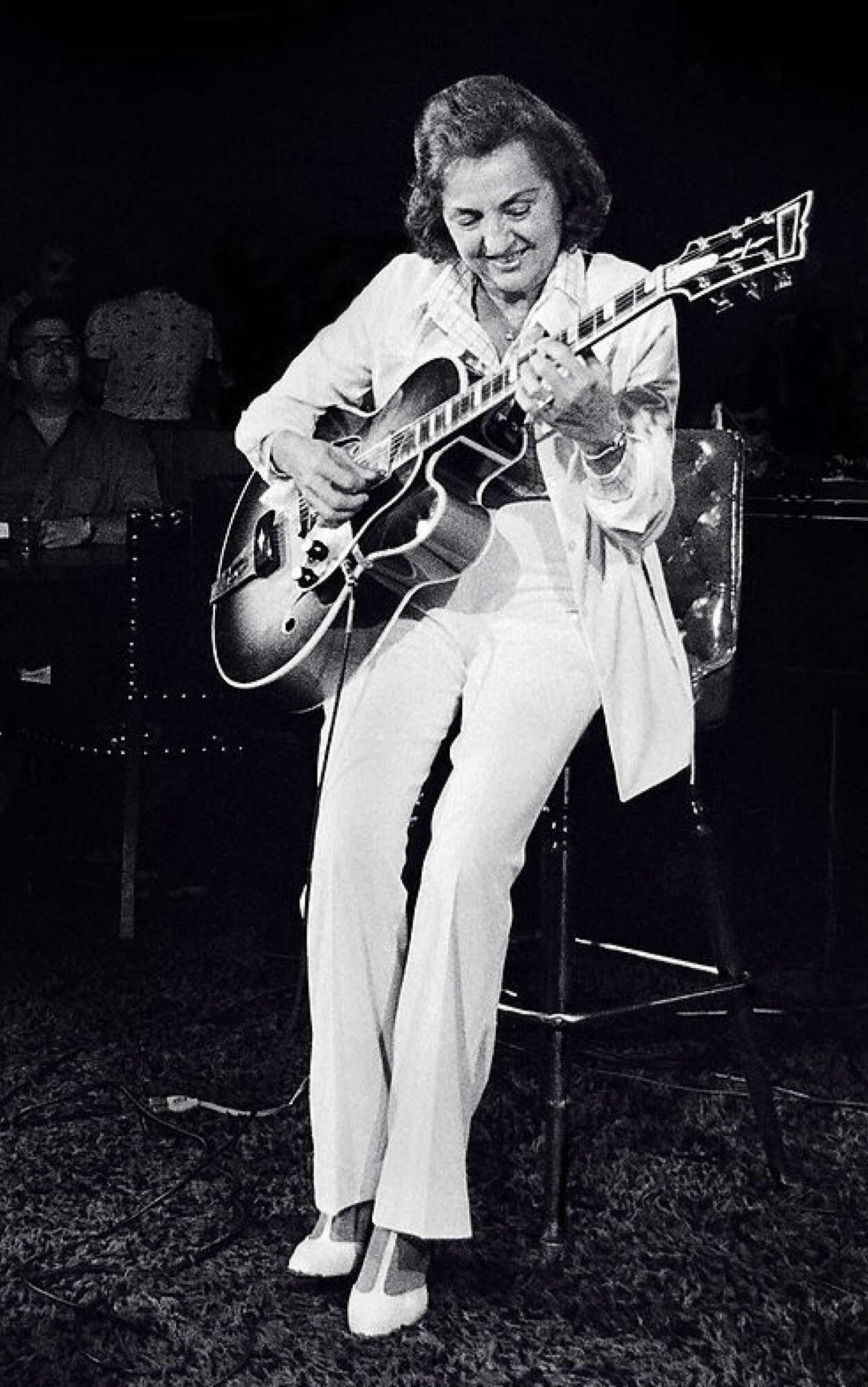

Osbourne in her later years.

In 1940, she married trumpet player Joe Scaffidi and moved to New York City. She began sitting in, in jazz jam sessions on 52nd Street, and playing with some of the biggest names in jazz, including Dizzy Gillespie, Stuff Smith, Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins, and Thelonious Monk. In 1941, she toured with jazz violin pioneer, Joe Venuti. Venuti’s previous guitar partner had been Eddie Lang, known as one of the first major jazz guitar soloists.

I first became aware of her on an album, led by Marion McPartland, called Now’s the Time. Marion had put together an all-woman ensemble, including Osborne on guitar, Lynn Milano on bass, Vi Redd on alto sax, Dorothy Dodgion on drums, and Marion on piano. Mary also performed in the first Kansas City Women’s Jazz Festival in 1978, among others. She recorded with Mary Lou Williams, the Beryl Booker Trio, Mercer Ellington, Ethel Waters, and R&B star Wynonie Harris, among others. In 1968, she and her husband moved to Bakersfield and founded the Osborne Guitar Company. She continued to teach and play locally in the Los Angeles area, and lived in Bakersfield until her death in 1992, of chronic leukemia. She was a formidable and swinging guitar player until then.

BARBARA LYNN 1942-Present

Barbara Lynn

Barbara Lynn, known as the “Empress of Gulf Coast Soul,” was known for her left handed electric guitar playing, soulful singing, and songwriting. Her 1962 hit, “You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” is probably her best-known hit, but others were also recorded by Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin (“You’ll Lose a Good Thing”), Freddy Fender, and the Rolling Stones (“Oh Baby We Got a Good Thing Going.”)

Lynn was born and grew up in Beaumont, Texas, right on the Texas-Louisiana border. She was inspired by Elvis Presley, Brenda Lee, and blues artists Guitar Slim and Jimmy Reed. She began performing in local clubs in Texas, and soon got a recording contract with Jamie Records in New Orleans. Max Rebennack (aka Dr. John) was a session player on her first recording of “You’ll Lose a Good Thing.” That song was number one on the U.S. Billboard R&B chart in 1962.

To support the single, she went on tour with Sam Cooke, Al Green, Carla Thomas, Ike and Tina Turner, Jackie Wilson, and Stevie Wonder. She appeared twice on American Bandstand, and several times at the Apollo Theatre in Manhattan.

At that time, she was definitely an anomaly. It was rare for any woman to be an electric guitar player (left-handed even more rare), with a distinctive contralto voice, who wrote her own material. She eventually signed with Atlantic Records but became frustrated with their lack of promotion. She married and had three children, then retired for the next 20 years. In the ’80s, she came out of retirement, did several European tours, and, in 1984, toured Japan. She was honored with a Pioneer Award, in 1999, by the Rhythm & Blues Foundation and played the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. She appeared in the R&B documentary I Am the Blues, and was the recipient of the National Heritage Fellowship, awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts, the U.S. government’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. Called the “Black Elvis,” she is a vastly underrated artist from the fertile Gulf Coast area. Her credentials are amazing and were established before she was even 23 years old. She continues to be active and recently celebrated her 84th birthday.

Sue Palmer has been a San Diego musician and resident her whole life. She has received numerous San Diego music awards as well as an award for Best Self-Produced CD from the International Blues Challenge in Memphis. She was inducted into the San Diego Music Hall of Fame, has recorded 30 podcasts, and hosted her online radio show for three years on the local jazz and blues radio station, KSDS Jazz88.3.