Cover Story

Mark C. Jackson Has a Story (or 3) to Tell

“A little water on a cold day to wash your hands with is a good thing.” —Zebadiah Creed

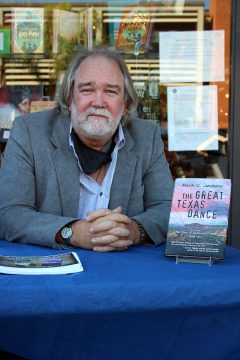

On a beautiful Halloween Saturday, my good friend Mark C. Jackson came to my home for lunch and a conversation. There would be a lot to talk about. Award-winning novelist, singer-songwriter, musician, composer, podcaster, raconteur, and bandmate, a conversation with Mark is an adventure that spans several centuries. From his historical fiction novels set in the 1800s to his early to mid-’90s collaboration with Peter Bolland, to the Mark Jackson Band, and to his recent podcasts in the Legends of the Old West series about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which include his original composition of the theme music, his ideas, stories, and songs reach out to readers and listeners from times past, present, and future. They say that old dogs can’t learn new tricks but that surely isn’t the case where Mark is concerned. Case in point: his writing for the podcast. There is nothing more representative of the 21st century than online presentation of content.

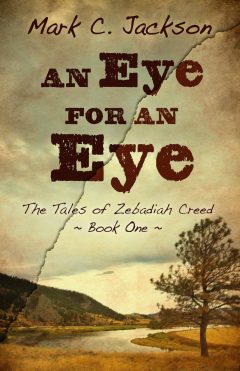

Writers have to have a voice whether it’s their own or one that they adopt by way of a character. Certainly, one of the strongest voices in Mark’s head is that of Zebadiah Creed, the protagonist in his novels An Eye for an Eye and The Great Texas Dance as well as the third book in the trilogy, the still-in-progress Blue Rivers of Heaven. Zeb’s quotes are interspersed within this story so that the reader can hear from the man directly. But Zeb isn’t the only voice in Mark’s head. As he’s mostly known as a songwriter, his personal voice is strong and resonant. I decided to begin by asking Mark how he started writing, recognizing that there are many different types of writing: songwriting, novel writing, podcasting, journaling. How does he adapt to the differing demands of each medium?

He started as a songwriter over 30 years ago, writing his first song in 1978 when he was still in the Navy. That song was called “What the Hell Am I Doing Here?” which, surprisingly, was a country song about “floating around in the middle of the ocean.” That was the first of many songs between then and 2011, which has yielded three Mark Jackson Band CDs: 2002’s Vigilante Road, 2005’s Love May Take the Long Road Home, and 2009’s A Real Charmed Life, which had production assistance from Grammy-winning producer Alan Sanderson. Mark has been nominated by the San Diego Music Awards seven times but has yet to win, which he jokingly says makes him the “Susan Lucci” of the SD Music awards.

“Nothin’ I say today means much, for soon I’ll be dead and the world spins on.” —Zebadiah Creed

It was music that brought me together with Mark C. Jackson. The Mark Jackson Trio had been recurring guests on a residency gig I had at Rebecca’s Coffee House in South Park and I sat in with his trio on four occasions between 2011 and 2014. Even with no rehearsal, Mark’s songs laid under my fingers quite well yet were challenging enough that they really required close listening to play them correctly. Mark’s songs have a way of drawing you in a little deeper each time you hear them, and this was certainly the case for me at every opportunity to play with him. Perhaps it was inevitable that we would eventually be playing together again…

Mark Jackson Band, Rock Valley House Concert, 2009.

One evening while practicing guitar, I started playing a song that was strange and yet familiar, soon realizing that it was Mark’s song “Lost Time on the Old Highway.” That song, working its way into my consciousness, was to me a sign that I should get in touch with him. Mark was glad that I called but he explained that he was in the middle of writing his second novel and really had no time to play music. He asked me to give him a call in a few months as he hoped to be finished by then. “A few months…” ended up being more than a year, but in early 2019 he came to my house “just to jam” and see what it sounded like. We fell right in with each other and with the songs that afternoon and agreed to get together again very soon.

“It ain’t hard to figure out how deep to go with only three inches of soil.” —Zebadiah Creed

Our next meeting was more focused and productive. Part of my study was to really listen to the lyrics of the songs. Mark’s lyrics are indeed special and intriguing, easily conjuring up visual stories in the listener’s mind. During our interview for this story, I told him that when I listen to “Lost Time on the Old Highway” I envision a lonesome two-lane highway somewhere in a desert where one might come upon an oasis of sorts, where there is a gas station, a store, a restaurant, and maybe a post office. There are two guys sitting at a table having coffee and talking as the sun sets over the distant mountains. Mark said that was exactly what he was intending to happen when he wrote that song. In fact, he said it was always his intent to create those sorts of “mind pictures” with his lyrics. He certainly succeeds quite regularly. That lyrical prowess certainly foreshadowed his success as an author.

“I suppose all of us have an itch we just can’t get at.” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark decided that we needed to gig as soon as possible. What had started as an idea for the two of us to play some coffeehouse duo gigs immediately became much more than that. He said that we should invite David Morgan to play steel guitar with us, an idea that quickly expanded to adding Jason Postelnek on bass and then David Wilke on drums, all alumni of the Mark Jackson Band and familiar with his songs. Within a day of that second meeting, Mark had set up two gigs for us. We had one rehearsal with David Morgan and Jason and played our first gig a week later where I met Wilke for the first time. With only one rehearsal as a band and playing with the drummer for the first time on the actual gig, it could have been a disaster, but everyone just fell into the songs like no time had passed. We played three more gigs, getting better and tighter each time. Then COVID hit and postponed everything. We haven’t played in a year.

“Ya hear that? It’s the mountains crackin’. Not in two, mind you, just a little every now an’ then. Ya gotta listen, and when you hear it, feel it, ya realize, that’s your soul crackin’.” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark’s first foray into writing outside of songwriting was inspired by a vivid dream he had while in his 20s. Remembering that dream after many years inspired him to write a 600-word short story called “The Hanging,” where we are first introduced to the character Zebadiah Creed. Or perhaps that’s where Zeb revealed himself to Mark. In our conversation, Mark told me that in that dream he was Zebadiah Creed who came upon the scene of a woman who was hanged by her husband for her infidelity with his brother. That short story was followed by a 5,000-word story, tentatively called “Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans.” In 2010 he started writing some poetry—some of which was published—and in 2011 he took a class in flash fiction with the San Diego Writers, Ink, which offers writing classes and workshops and sponsors writing events. (The definition of flash fiction is to write compositions of 1,000 words or fewer). He was then 23,000 words into “Zebadiah Goes to Texas” when he met Chet Cunningham in 2012, the man who would become his writing mentor and friend. Mark told me that Chet loved “The Hanging,” hated “Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans,” and is fairly certain that he never read “Zebadiah Goes to Texas.” But based on his impression of “The Hanging,” Chet invited Mark to join the oldest writers group in the city, The San Diego Professional Writers Group, which Chet had founded in the ’60s. Advised to “just show up and listen…” and appropriately terrified—these people were real writers after all—Mark attended his first meeting. Heeding that advice, he was able to suss out how the meeting worked so he was as least a little prepared when, two weeks later, it would be his turn to read for the group. It was at that second meeting when Mark read “The Hanging” for the group to critique. Listening to the others reading chapters from their latest books, he again wondered if he really belonged there. When it was his turn, he nervously read his piece. Each member had something different to say and he anxiously scribbled down their comments. Mark told me that he still has the copies with everyone’s handwritten comments on them. The group praised his work, so he was invited back for the next meeting in two weeks. The experience left him thinking he might actually have some potential as a writer. How true that intuition was as the nascent story “Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans” became his first novel, An Eye for an Eye.

“Ya know how to write a book? You sit down with pen an’ paper and write it.” —Zebadiah Creed

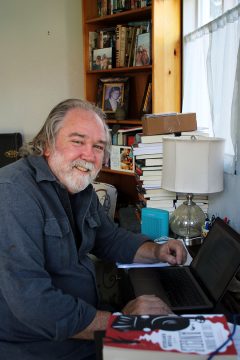

When you decide to write historical fiction, it better ring true. I asked Mark about how he goes about researching for the books. True to a modern-day approach he told me that Google is a wonderful tool. If he wants to know, for instance, how duels were staged in 1835 in New Orleans, he just Googles it and everything you want to know is right there for the reading. That information provides the factual component to the story. The artistry come in how those facts are woven into the fictional narrative and molded to fit the characters in the story. I had asked, “Do you imagine the story from beginning to end or do you start and let it develop?” He said that he just writes and lets it happen, usually not knowing what is going to happen until he writes it. Sometimes, it is the research itself that can drive the story. The ending of An Eye for an Eye was somewhat unknown until Mark did some research into a pirate named Jean Lafitte. A random story, speculating that Lafitte hadn’t died off the coast of Veracruz in the wreck of one of his pirate ships but rather had survived and made his way to St. Louis to live the remainder of his life in relative anonymity, gave birth to a character named “Frenchy,” who would play a pivotal role in the telling of the story. That then informed the plotline for the second and third books. I’d planned to ask if he used the technique of writing the ending first and working backward, but that was obviously not the way he approaches it. But there’s more than just “letting the story tell itself.” He shared a story about a scathing critique he received from Chet Cunningham regarding the “Zebadiah Goes to New Orleans” story. Mark had written the expository of Zeb’s backstory from Zeb’s point of view and thought it was enough that it was told by Zeb to another character in the story. Chet insisted that Mark had to take Zeb back to the origin and tell the story as he would have lived it, not just as a conversation. The other members of the Writers Group all agreed, so that’s what he did. It was a lesson well learned; if you’re going to tell a story, you have to tell all of the story, not just mention parts of it from the point of view of a character. Do the work and allow readers to experience things for themselves in the context of the story. In doing that work, Mark found that the story opens up and, in effect, begins to tell itself as much to him as it would to the reader. It was in writing the backstory that he found—or invented—the character of Frenchy who then inspired him to do the previously mentioned research into Jean Lafitte and enable him to fill out the character into something, or someone, who is believable and adds depth and direction to the story.

“I don’t need no one to stand up and lie for me, I can do that just fine myself.” —Zebadiah Creed

One of the more difficult things when creating a story arc—as Mark has done with the Zebadiah Creed trilogy—is keeping track of the story. As he writes, he has to constantly reference previous chapters, or even previous books, to make sure that everything remains consistent and that that loose ends get tied up, or as he puts it, “remembering what I made up….” He cites The Writer magazine and Writer’s Digest as two sources that were instrumental in his learning to write. That and his participation in the Professional Writers Group taught him what he needed to know to be successful. I mentioned that he had very obviously learned and internalized those lessons. “I’m an award-winning author,” he replied. That’s a fact. And listening to and heeding the advice of professional writers has made him such. That’s the easy part. If nobody likes something he wrote, it probably isn’t very good. He went on to say that the tricky part is when they disagree over the same piece. Someone would say, “That’s terrible,” and someone else would say, “That was the best part.” Then he really has to decide what works for him and the story being told. Does it work as-is or is there a better way of saying it? He’s reached a point now where those decisions are clearer and easier to make but still, he listens to their input. In the end he knows it’s his story and he needs to own what he’s written.

“I never have been good at owning things, why start now?” —Zebadiah Creed

I was curious about how he creates characters for his books, and I wondered how much of himself is in his characters. Mark said, “Well, I’m pretty much Zeb,” which he had alluded to earlier when he was recounting the dream that inspired “The Hanging.” He said that Zeb is a character whom he’d like to think he could be if he had been alive in 1835. He believes that he would certainly be that flawed individual who watched the Lakota murder his parents and was then taken in as a slave with his brother, eventually becoming a warrior by enduring the Sun Dance. The time in which Zeb lived was a violent and lawless time where justice and lives were brokered and decided by the highest bidder. Yet Zeb is able to retain his sense of morality and code of justice in his own way. He further said that he had to think—or live—as he imagined Zeb would, since the books are written in first-person narrative. The only way that he knows how to the maintain that reality is to speak as Zeb the best way he can. One of the things I really wanted to know was if he used other people—real people he knows or knew—as inspiration for his characters? Mark told me that he really only used two people as characters, one of whom was a guy he worked with. This real person-inspired character appears in the last third of An Eye for an Eye and reappears in the third book. He is a “Freedman,” an African-American or Black man who had been freed from slavery, a description that prompted a digression in our conversation relating to race. Mark said that that wouldn’t have been the terminology used in 1835 and that Zeb didn’t speak that way, but he did use that very term we are all thinking about in the book when it was character appropriate. Neither he nor his publishers believe in censorship when something is necessary to tell the story. I mentioned that Mark Twain used that term when he wrote Huckleberry Finn. Mark interjected—and we agreed—that Twain did that to bring fullness and reality to the character of Jim and also to point out the inherent racism of the times in which he lived. It was absolutely Twain’s intent to shame white people for their behavior and while he is too modest to put himself into a comparison with Twain, I believe that Mark uses the term for the same reason in his novels.

“Fate don’t mean nothing ‘til you see it first-hand.” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark continued to tell me about that real person from his life who inspired the Freedman, a young fellow he once worked with named Olgens Pierre. That was an OMG moment where Mark realized that that was who this character was. He went home that night envisioning a fully formed, suave black Freedman and the character became real to him. In the 1830’s New Orleans was a potpourri of ethnicity, with Creole, French, Spanish, some Americans, Freedmen, and slaves all enmeshed in a turbulent and colorful society. He went back to work two days later and asked Olgens permission to use his name for a character in the book he was writing. Receiving permission, Mark asked him, “How did you get the name Olgens Pierre?” He replied, “Well, my parents are from New Orleans….” Then it gets weirder. Olgens went on to say that his parents were from Haiti, the location of the first—and only—successful slave revolt in all of the West Indies. They eventually kicked the French out and created their own country, their own Republic, consisting almost entirely of former slaves. With the character now completely clear to him, Mark went on to have Olgens Pierre play an integral part in the ending of An Eye for an Eye and the character is reintroduced in the third and upcoming book Blue Rivers of Heaven.

“There’s a whole world in a tear.” —Zebadiah Creed

Following that revelation, I asked Mark if the writing sometimes gets too personal and, if so, how does he deal with it? He told me that indeed it does. One time he was writing a scene where a character named Billy Frieze, an Englishman whom Zeb doesn’t entirely trust but needs to know in order to navigate the underworld society, has something tragic happen to him. Mark said that after writing that scene he was in tears. He said it was so intense and so real because he had lived with Billy for so much of the book that it was very, very hard to write that scene. He went on to say that it’s not every day he writes something like that. He often gets excited while writing a scene, but it is only when he has finished that he knows the truth of the story and that is when it becomes real to him. Only then can he react emotionally to what he has written. Mark said (and I think this is good advice for all creative people regardless of the medium), “We talk about the Muse and how it flows through us. And I don’t know if it’s some subconscious or super-conscious state, but I just know it’s working for me and I’m not going to screw it up. I’m not going to dampen my emotions or my connectedness to that flow just because they might embarrass me.”

“How can anything be more important as lovin’ somebody?” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark’s inspiration to write was formed much earlier than even his joining and participating in writing classes and discussion groups. He recalled a time when he was five years old, watching his grandmother Fayette create a poem from nothing but her imagination. When she finally finished, she read it aloud, and the words came alive. He didn’t understand it at the time, but he was fascinated with the rhythm and rhyme, with the structure of the language, and the beauty of the words. She sent the poem to the Daily Oklahoman to be published. A few weeks later, there in the arts section next to the crossword puzzle, was his grandmother’s poem with her name, Fayette Glass, written below. “Everyone can read it now,” said his mother, Judith Ann Jackson, who would prove equally as inspiring to him.

“Whenever I start thinkin’ I’m absolutely right, someone always comes and proves me wrong. For that, my friends, I am truly grateful.” —Zebadiah Creed

During our interview, Mark shared a story about a conversation he had with his mother. He was about a third of the way through the writing of An Eye for an Eye when he happened to call his mother and she asked him, “What are you doing?” He said, “I’m writing.” “Well, what are you writing?” So, he read her the chapter he was working on at the time. She told him that was good but there are some things in there that don’t work. He asked what and why, and she told him in detail what needed to be changed. He recollected a scene from the story set in Frenchy’s Emporium with a pit and two wolverines. There was a man—who had been accused of hitting one of Frenchy’s girls—in the pit with one wolverine and trying to stay alive under attack from this vicious animal. Zeb is witness to this form of western justice and it’s all new to him. The victim in the pit survives by killing the wolverine, then a second wolverine is released into the pit. Zeb thinks this is just too much, believing that since the man survived the first wolverine he deserves to live. Zebadiah pulls his long knife, jumps down into the pit, and kills the second wolverine. That’s how the scene reads in the finished book. But it wasn’t how Mark originally wrote it. When he finished reading her that scene, she said, “Honey, Zebadiah has to jump down into that pit and kill that wolverine and save that man’s life.” Mark knew then that he had a writing partner. He dedicated the first book to his mom, and she has been a constant partner for the better part of two and a half books. Even as recently as the day before our interview, Mark was on the phone with his mother and, once again, she came up with a plot suggestion that made the chapter work. Mark believes oftentimes that she knows Zeb better than he does, but that’s because she knows her son.

“No one’s more important than a bird’s song.” —Zebadiah Creed

Circling back to his music, I asked Mark how writing historical fiction compares and differs from writing song lyrics? “Well, the length for one,” he answered. “The first book was 58,000 words. The second was 83,000 and I’m 40,000 words into the third one.” He is also working on some science fiction short stories that will most likely be published in journals of some kind. There is a specific structure to both storytelling and songwriting, but the biggest difference is that songwriting requires brevity. Songwriters must have the ability to use very concise language, roughly 50 to 60 words—with a repeating chorus—to tell a story and engage an audience that usually has a very short attention span. Every word, every syllable must count. He has been able to take that discipline and become a successful songwriter, and subsequently expand that discipline into becoming a writer.

“Used to be a thin, young man. Never dreamed I’d be a fat, old man.” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark first entered the San Diego music scene in a duo with former Troubadour columnist Peter Bolland. To add diversion and bring some history into the conversation, we called Peter to talk to him about how he and Mark came into San Diego’s music scene. They first met when Mark was a student in one of Peter’s philosophy classes. An after-class discussion and a shared love of Neil Young evolved into playing together and writing together. They played many of the local coffeehouses—places like Java Joe’s, Mikey’s, and Papa Dave’s Coffeehouse in Chula Vista—which were the venues for acoustic music and became the genesis for many of the singer-songwriters that evolved from that scene. Peter credits Mark for encouraging him and for them to keep performing and push forward to develop their writing and performing skills. The realization that the audiences were actually applauding for a song that they had wrote proved to be intoxicating and launched them into recording their first—and only—Jackson~Bolland cassette from 1996: LIVE at: A Better World Galleria. They reminisced about all of the gigs they played together and both agreed that the high point of their association was opening for Arlo Guthrie. They eventually went on to pursue separate but parallel paths where they established their own bands and recorded their own albums. One thing Peter mentioned, which Mark and I had discussed, was how important it is to get to the point when writing a song. “Stripping out everything out that doesn’t need to be there” is how he put it. And Peter mentioned how Mark transferred that skill into writing novels, which has definitely made him a better writer.

“These white men of religious pomp and power will go the way of the wind and die, leavin’ us to a calm, sunny afternoon.” —Zebadiah Creed

I asked Mark what else about his creative process is important for him to share? He said it requires a certain amount of discipline. The first two books were written at night and on weekends while he still had a day job. Being a member of his writers group helped him by having someone to answer to in order to get things done. Committing to a deadline—“putting a stake in the ground” is how he put it—is also a way that keeps himself engaged and makes him finish his writing projects. As he approached retirement from the day job, he rearranged his life to make room for writing and changed his daily schedule to facilitate the process of writing. He said that he doesn’t really consider himself retired, but rather he transitioned to being a full-time writer. He is also a judge for the prestigious Spur Awards in conjunction with the Western Writers of America.

“The only thing I can trust to let me know I’m alive is my breathin’.” —Zebadiah Creed

Mark’s most recent published writing has been for the podcast Legends of the Old West series. The four episodes in the series that Mark wrote are about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, available on Apple Podcasts. The installments are titled Butch & Sundance Ep. 1 | “From Cowboys to Outlaws,” Butch & Sundance Ep. 2 | “Rustlers and Robbers,” Butch & Sundance Ep. 3 | “The Wild Bunch,” Butch & Sundance Ep. 4 | “Bolivia.” In addition to writing the episodes, he and David Morgan wrote and recorded the theme music that plays during the credits. Be sure to visit Mark’s website https://markcjacksonwriter.com/ and have a listen to his newly released song “Cowgirl’s Lament,” written by Mark along with David Morgan, Pamela Haan, and Chris Enss, who sings the song. I didn’t realize that it had been nearly a year since we’d played live until Mark mentioned it. We’re hoping to be able to get together when our schedules permit and I am certainly looking forward to the time when we can once again play Mark’s songs for people again.

LINKS

Live interview with Charlie Loach and Mark Jackson:

https://www.reverbnation.com/markjacksonband

https://markcjacksonwriter.com/

https://www.facebook.com/Writermarkcjackson/

http://www.sandiegowriters.org/

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/butch-sundance-ep-4-bolivia/id1362910749?i=1000499144245