Unsolicited Advice

It Was a Horse (It Was a Mule)

I initially thought of calling this monthly column “A New Yorker in California.” There are multiple differences in communication style between the country’s two farthest edges, and they are exactly and comically at odds with each other. This often makes each coast feel like a foreign land to folks from the other. There are many columns’ worth of content around this cultural mixed marriage.

The biggest difference, perhaps, is in how each demographic, to quote A Few Good Men, “handles the truth.”

I often hear something along the lines of, “I am asking you because I know you will tell me the truth,” from my California friends. They perhaps mean it as a personality trait, and it might well be. But to me it is also a holdover from my New York upbringing.

There is a sociological difference in how each coast handles “tough truths.” On the West Coast, people are brought up to protect a person from potentially hurtful feedback. So after, say, a tough game, you might say, “That was a really tough situation, I don’t know if anyone could have done any different. You should be proud of yourself.”

On the East Coast, we are brought up to fully embrace the “fact” but separate it from the person as a means of taking away its potential to hurt us. So, after that same tough game, we might say something closer to, “Yeah, this wasn’t your best day. But you’ll get them next time.”

East Coasters reading the West Coast example probably winced a bit, just as West Coasters reading the East Coast example likely did.

This goes deeper than mere communication style. On the East Coast, we are socialized to believe that the direct approach is a sign of respect, and that, conversely, if you have a tough game (or make a mistake, or trip while walking into a room, etc.), and no one mentions it, it is because they just don’t regard you highly enough or like you well enough to bother being honest about it. I mean, we all saw what we saw, so why isn’t anyone saying anything?

On the flip side, West Coasters would find it rude or disrespectful to tell someone who just had a bad game (or made a mistake, or tripped walking into a room) that it was definitely noticed by all who watched. I mean, we all saw what we saw, so why would anyone need to say anything?

And never the twain shall meet.

(Well, actually, they do meet, in a way, in the middle of the country. The devastatingly effective “bless your heart” manages to perfectly thread the needle between “Yeah…no” and, “…But it’s sweet that you think so.” But that’s a different column.)

That last point is the one I want to talk with you about this month. Because it is significant that the same language or action that one person might think of as respectful, could be heard as specifically disrespectful by another. In fact, it is the root of almost all human misunderstanding, beyond the context of any East/West dis war.

Even something as simple as a Trader Joe’s check-out person asking what we are doing today might hit an East Coaster’s ears as an almost insulting boundary violation and a West Coaster’s ears as a laudable means of connection. And both sets of ears are correct, in the context of their owners’ own “truth.”

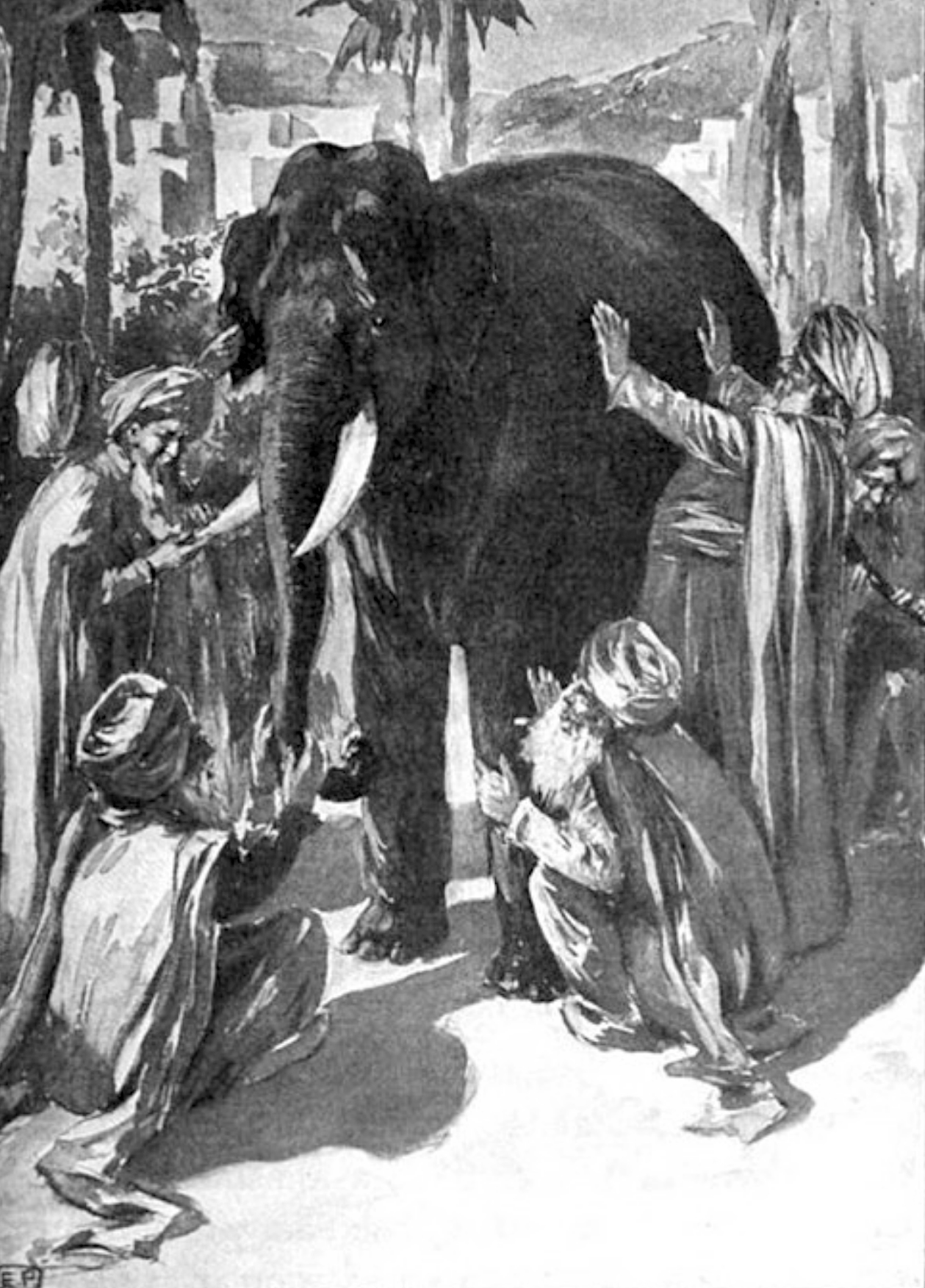

I have always been fascinated by the malleable definition of “truth.” In every instance, truth is accompanied by an unstated asterisk that says “as I experience it.” The Buddhist parable of the blind men and the elephant explored this concept as far back as 500 BCE. The parable goes roughly like this (I am quoting the below from E. Bruce Goldstein [2010]. Encyclopedia of Perception. SAGE Publications. p. 492, which I found via everyone’s favorite crowd-sourced online dictionary):

A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: “We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable.” So, they sought it out, and when they found it, they groped about it. The first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said, “This being is like a thick snake,” For another one whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg, said, the elephant is a pillar like a tree trunk. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, “is a wall.” Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth, and like a spear. In some versions, the blind men then discover their disagreements, suspect the others to be not telling the truth, and come to blows.

Even more central to this concept is the opening scene of the musical Fiddler on the Roof, which tells of an argument that has been brewing for apparently decades over whether an animal sold by one villager to another was a horse or a mule. Half the town says horse, the other half says mule. The dispute continues to their present-day. And of course it’s the same animal. So how can half the people be “right” and half “wrong”? And which half is which?

Well, neither and both. In a time and place when polarization has become not just standard, but almost celebrated, it can be tempting to dismiss another person’s truth as delusion. And yet I can’t tell you how often I’ve discovered, in retrospect, that a disagreement hinged on a single word that meant something positive to one person, and something negative to the other. That is, an honest dispute over language, rather than bad intentions or disingenuity. Yet we often experience it as the latter.

What I want to propose to you this month is two fold. In any interpersonal interaction where hackles are raised,

- Consider believing. If the person spoke Lithuanian and you spoke English, you would have to take their word for it about how their language worked and what something might mean. Try that “in English” as well. Play what philosophers sometimes call the “believer’s game” and view the disconnect as a matter of language, not of intention. Language in this sense can mean delivery style as well. Be curious and interrogate the rift. Presume you are two people (or sides) of equally ingenuous truths and try to figure out how the same issue could be legitimately seen as a “horse” by one and a “mule” by the other. Maybe even temporarily abandon your insistence on the horse and try on some arguments in favor of the mule.

Remember that your truth is as arbitrary as the other person’s; you might as well check out how the other half lives before walling off that portion of the city forever.

And…

- Try speaking the other’s language now and then. Just try it on. In my NY/CA example at the beginning of the column, maybe this means an East Coaster remembering that the West Coast receiver of your comments will hear directness as an aggressive personal critique and finding a “true” way to talk around the “flaw” itself in the language of the listener. And flip side, maybe it means a West Coaster offering the East Coast recipient of your feedback, something more direct than you would normally deploy, lest your avoidance be heard as dismissiveness. The old “honest answer to an honest question” routine.

The result may not be perfect. It won’t be comfortable. But neither is arguing. And at least this way there is a chance for what starts in conflict to end in concord.

Even if it was obviously a horse.