Featured Stories

Did Spotify Kill the Radio Star? Ask Joel Rafael.

Radio’s dead, right?

Joel Rafael in his studio.

You remember radio—that AM/FM thing with the tuning knob you’d fiddle with to get a signal? Maybe it was the clock radio beside your bed lulling you to sleep with the schmaltzy request-and-dedication show. Maybe it was the car radio on that three-hour stretch through Nevada when you hoped Casey Kasem would announce the number one song of the week before being swallowed in static. Maybe it was the stereo in your living room where you’d dash across the room and bash your shin on the coffee table so you could press “record” and “play” simultaneously on the cassette deck. Wherever you heard it, radio was king, and we were its loyal subjects.

But now that we have 24/7 on-demand access to nearly every song ever recorded, why would we relinquish that control? When an algorithm can predict with terrifying accuracy the kind of genre, song, artist, and instrumentation most pleasing to my ear, why would I trust some unknown schmo to curate my listening experience? Can’t me and Spotify handle the job?

To find the answers to these questions, I went to local folk icon Joel Rafael. Rafael, if you’re not familiar, has been writing, singing, and touring for over 50 years. He’s a torchbearer of the genre, with a particular bent toward preserving the music of Woody Guthrie through playing his songs, performing at the annual Guthrie Festival, and even co-writing songs with Woody using the lyrics Guthrie’s daughter entrusted to him. He’s also a founding member of the Java Joe’s crowd, a clan of scruffy misfits who performed regularly at the legendary Poway coffee shop in the 1990s.

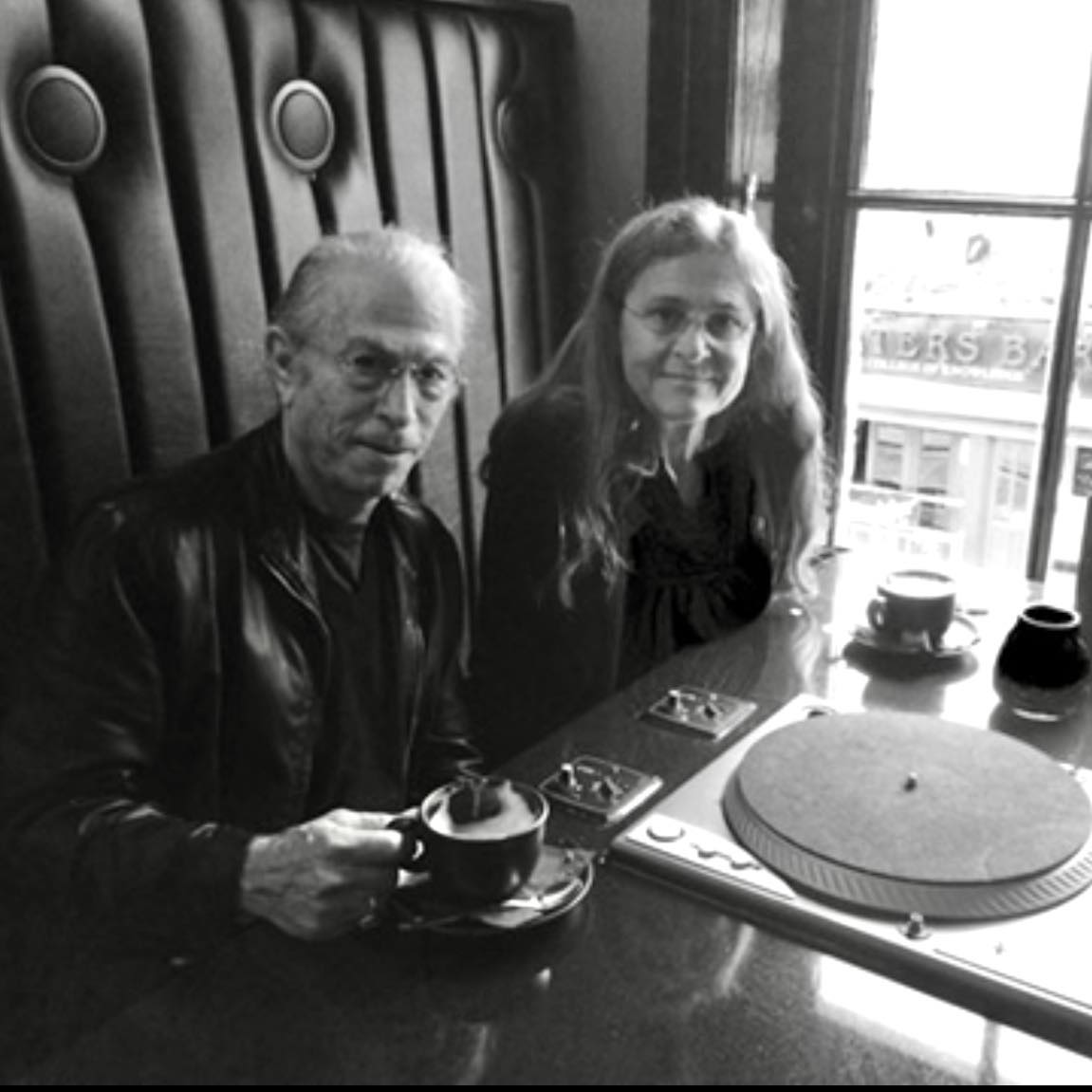

Rafael is the closest thing we have to a folk oracle—from dropping wisdom on the rules of recording to doing a spot-on impression of Pete Seeger during an encounter over a parking space. But what you may not know (I didn’t) is that Rafael and his wife Lauren have also produced a weekly folk radio show for the last 14 years, which airs six times a week on local and national stations.

“I’ve always loved radio. Like from the time I was a kid,” Rafael remembers. His fascination began with one of those aforementioned clock radios by his bedside and was later stoked by a friend who attended a private school in Claremont with a small radio station. “We’d go up there, and one person would be on the radio talking and the rest of us would be out in the car listening to it because the transmitter literally only went out to the parking lot.”

But Rafael had less success with stations that transmitted beyond their parking lots. “When I became a performing artist, one of the goals was to be on the radio, but it wasn’t an easy thing to do. I applied for an FCC license, and I went around to all these different radio stations and tried to get a job, any job at all. And it was such a locked-in community, I just couldn’t penetrate it.”

Enter KKOS, a Carlsbad station with DJs who got to know the Java Joe’s crowd. Rafael and his band put out their first CD in 1994, and KKOS began playing several of its tracks. Rafael recounts that clouds-parting, heavens-beaming, angels-singing moment: “you’d be driving along, just going to the grocery store or something, and all of a sudden your song would come on. It was pretty cool,” he admits with a grin. Every breathing musician would regard that as an understatement.

Breaking the radio barrier gave Rafael some national visibility, which led to more touring and interviews for comparable stations across the country. Around the time when satellite radio was coming into prominence, Rafael was even invited to guest host a one-hour folk program on Sirius XM. He had a blast, then he brought a disc of the recording home and tucked it away for a few years.

Fast forward to 2007, when numerous wildfires ravaged San Diego County, including land near the Pala Band of Mission Indians southeast of Temecula. With the short-term goal of creating an emergency alert network and the long-term goal of promoting their culture, the Pala Band created Rez Radio, the first indigenous-owned radio station in Southern California. Though Rafael “wasn’t even really hungry to be on the radio anymore,” the program manager was looking for shows to fill its time slots and Rafael thought, “well, maybe I should go down there and talk to the guy.” That conversation led to Rockin’ the Rez, Rafael’s program of 14 years that has produced a whopping 449 episodes. As part of the Pacifica network of public and community radio stations, it now appears six times a week on Rez Radio, Folk Music Notebook, Radio Free Nashville, and a few other Pacifica stations.

Rafael with his wife, Lauren

Rafael describes the program as a labor of love—it has to be since no one gets paid. It begins with his wife Lauren picking the songs from their shared collection, including a “good mix of contemporary and traditional stuff of people you’ve heard of and people that you haven’t heard of.” Once she compiles a CD, “we listen to it together and decide if it all kind of works,” sometimes changing the playlist order or swapping one song out for another. While the selections need not be political, Rafael explains, “we want songs that count and have something to say.”

Once the songs are finalized, Rafael loads them into his software and records his commentary, always announcing the artist and title but frequently adding stories and anecdotes if one of the musicians is a friend or “somebody I’ve met along the road.” Songs by Jimmy LaFave, Danny O’Keefe, and Eliza Gilkyson make frequent appearances, and he’s interviewed Arlo Guthrie twice. He appreciates the occasional e-mail from listeners complimenting the show or asking to repeat the name of an artist they enjoyed. “It really is heartwarming that people are out there listening.”

As these details reflect, Rafael regards radio as more than electromagnetic waves traveling through space. “There’s a history to radio that’s long and deep and comprehensive and sort of magical in its own story,” Rafael muses. “We live in a corporate world, and it’s becoming more dangerous all the time. But now the common people are starting to feel the effects of it on a daily basis because of our administration. So, radio could easily become way more important again because it’s attuned to the resistance of some of the stuff that’s going on and is vitally important for information.” In other words, the revolution may not be televised, but it might be on your stereo.

Rafael reminds me of some of the reasons I miss radio. The happy surprise of being exposed to something new and captivating that I didn’t choose. The discipline of bringing myself to listen to a program at the time it’s broadcasting, rather than summoning it on demand. The connection to an unknown person in a small windowless studio miles away with who unexpectedly says or plays something familiar or relatable. It might even be worth a little static and bruised shins sometimes.