Featured Stories

California Young Guns: The Birth of Country Rock, Part 2

This is the second of a two-part series, exploring the history of California country rock. In Part One, its link to the Bakersfield country tradition was explored. In addition, the circumstances that led to the Byrds’ landmark album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, were traced. This part will explore the evolution of the movement from the late ‘60s to the present.

PART 2

Screenshot

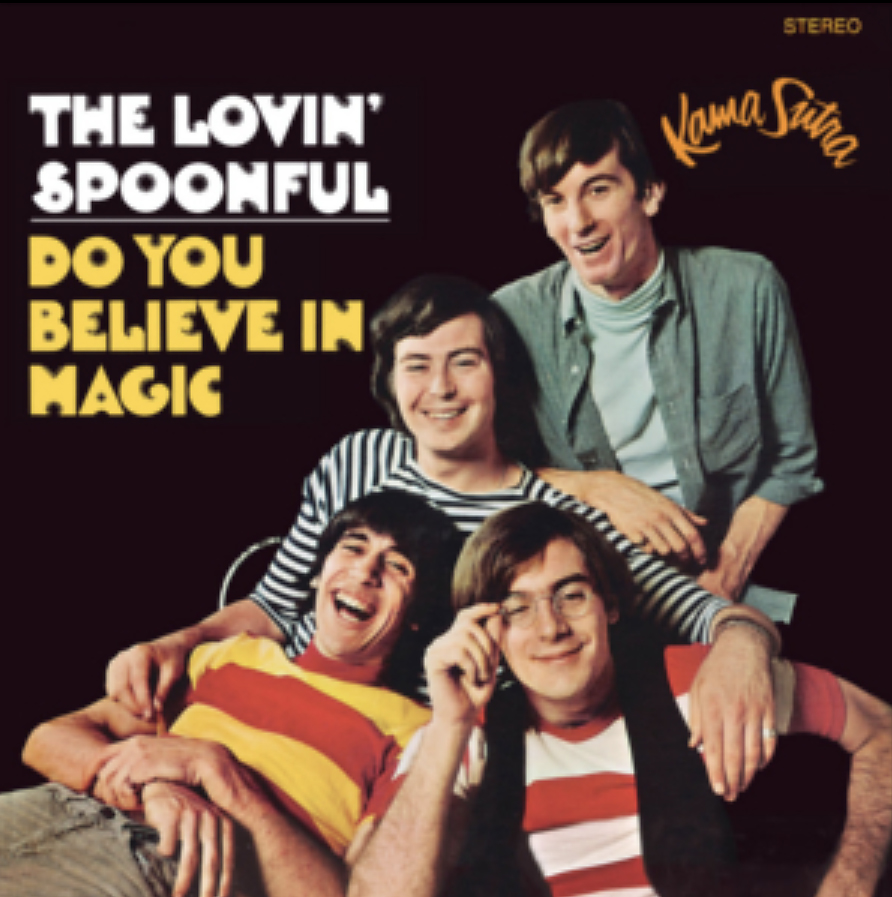

By 1968, American rock was undergoing critical changes. In the midst of all the psychedelic hoopla, Dylan’s widely acclaimed John Wesley Harding was released. This return to his folk troubadour role foretold the death of psychedelia. The Lovin’ Spoonful, Mamas and Papas, and Buffalo Springfield, all vanguard groups, would break up. Gram Parsons—soon to be followed by Chris Hillman—would leave the Sweetheart-era Byrds, while McGuinn would soldier on with a completely new line up. 1968 would also be the year that the term “country rock” was coined and along with this new L.A.-centered movement, a plethora of groups would form or reformulate.

In the same way that today’s alternative country bands have vast differences with musical interpretation, approach, and delivery, country-rock bands during its infancy period—1968-1969—were very different as well. The music of that time provides a still-useful template for identifying the genre’s sound. In November 1968, Doug Dillard and Gene Clark, late of the Dillards and Byrds respectively, released their debut album, The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard and Clark. Much has been said about the modern “new grass” sound, but Dillard and Clark were arguably the first to reinterpret classic bluegrass to produce a treasure trove of new bluegrass songs. On the other hand, the Dillards left their pure bluegrass base with the release of Wheatstraw Suite in December 1968. This innovative album merged the band’s bluegrass virtuosity and flawless vocals with electric rock instrumentation, orchestration, and country picking. Though both albums are quite different, their music has held up as examples of country rock at its best.

Soon after leaving the Byrds, Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons would partner up again to form the Flying Burrito Brothers. In the winter of 1968, they would release their first and greatest album, The Gilded Palace of Sin. With its blend of country and R&B, the album was a vehicle for Parsons’ version of “cosmic American music.” Songs on the album ran the gamut from sassy, up-tempo country rock to emotive R&B interpretations, to songs of heartbreak and disappointment, to social-political commentary. Of the album’s 11 songs, its nine originals were brilliant and often possessed insight built on the pain of experience.

Soon after the release of the Burritos’ debut album, Poco released its first. With the disintegration of the Buffalo Springfield, Richie Furay and Jim Messina would pursue their vision of country music with rock sensibilities. Their album, Pickin’ Up the Pieces, was perky and optimistic as contrasted to the seriousness of the Burritos. Indeed, both bands had distinct views of this new music. While Poco viewed the Burritos as more traditional country, the Burritos saw Poco as too whimsical.

The re-formed Byrds were also busy in 1969. With ace bluegrass and country picker Clarence White, the band released two new albums that year. The first, Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde, did not attempt to blend country and rock together into its songs; rather, the album consisted of separate rock, country, folk, and even blues numbers. But the album’s highlight was the Roger McGuinn/Gram Parsons-penned country-rock gem “Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man.” This young-gun classic lampooned Ralph Emery, Nashville’s premier disc jockey of the day. Emery had used his radio show to attack the Sweetheart-era Byrds as “hippie interlopers” prior to their guest appearance on the Grand Ole Opry. The Ballad of Easy Rider, released late in the year, provided a much better integration of country and rock styles into its song selection. This album is considered by many Byrds watchers as one of the group’s best vinyl efforts.

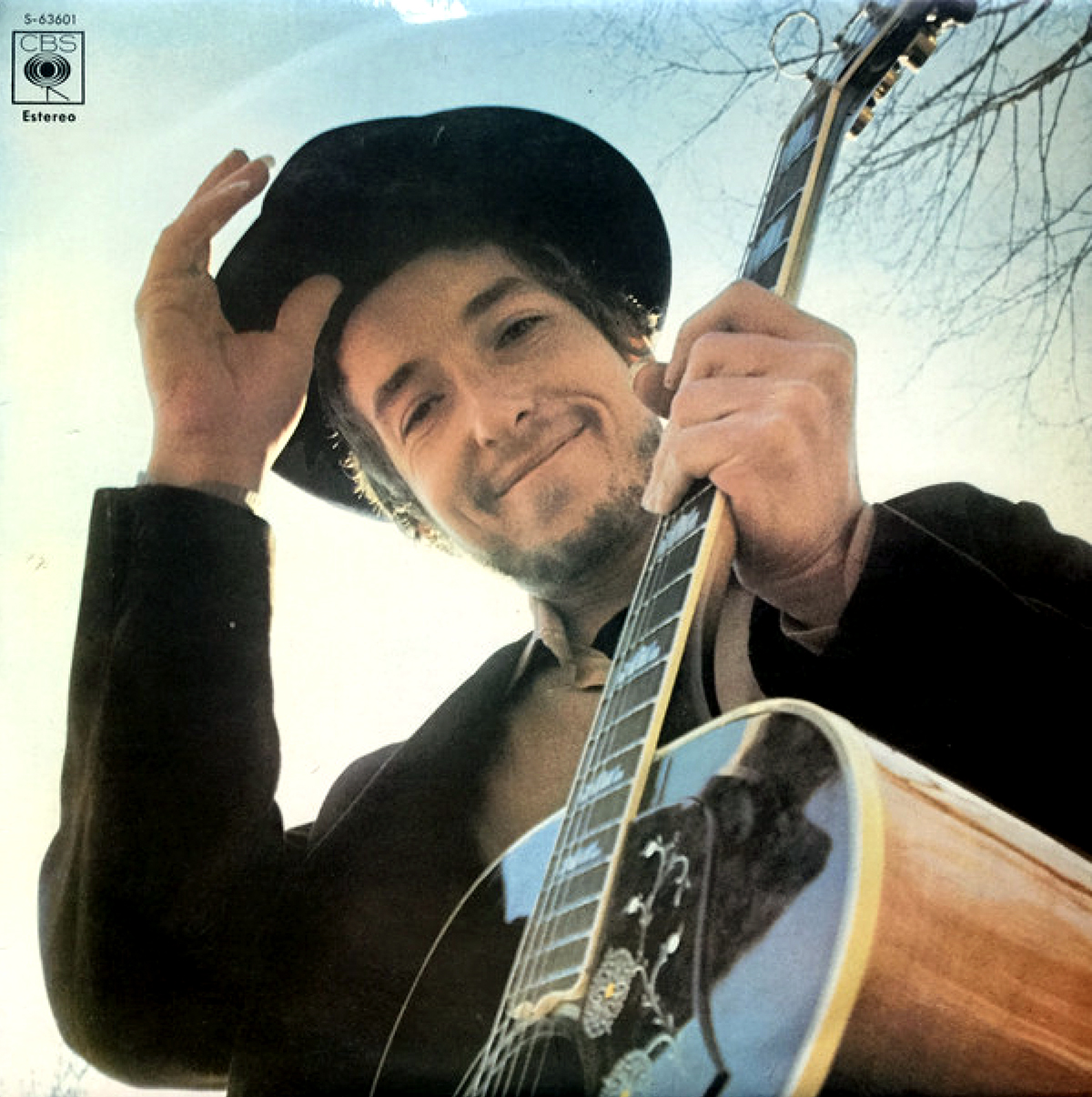

Dylan’s Nashville Skyline

During this nascent period of country rock, other young-gun artists and outfits would flesh out the new movement. By the end of 1969, quality works were put out by former teen idol Rick Nelson, ex-Monkee Mike Nesmith, Hearts and Flowers with former San Diegan Larry Murray, and transplanted Canadians Ian and Sylvia Tyson. And seemingly, though in a tacit way, Dylan appeared to give his blessing to the movement with the release of Nashville Skyline. Ironically, Dylan, voice of radical change and restless youth, worked well in Nashville and even won the admiration of country icon Johnny Cash. On the album Cash sings a duet with Dylan on “Girl from the North Country.” Later Dylan would guest on Cash’s popular television show.

But by 1971, the country rock movement began to hit snags. First, the music could never overcome the stigma that it was too country for rock and too rock for country. This resulted in little to no radio play on either format. Though Nashville Skyline was a successful Dylan effort, its popularity did not trickle down to the California bands. In efforts to appeal more to young audiences, Poco and the Byrds resorted to long-winded rave-ups that aped the excesses of rock. Though these jams may have been of interest in live shows, they only took up valuable space on vinyl. In the midst of these doldrums, partnerships and group cohesiveness began to dissolve. Gene Clark split from Dillard and Clark. John York was squeezed out of the Byrds. Gram Parsons’ demons, addictions, and erratic behaviors alienated him from his bandmates and he was sacked. Jim Messina left Poco to form Loggins and Messina. The fate of country rock looked bleak. The movement appeared to be floundering, but actually it was on the verge of its greatest period.

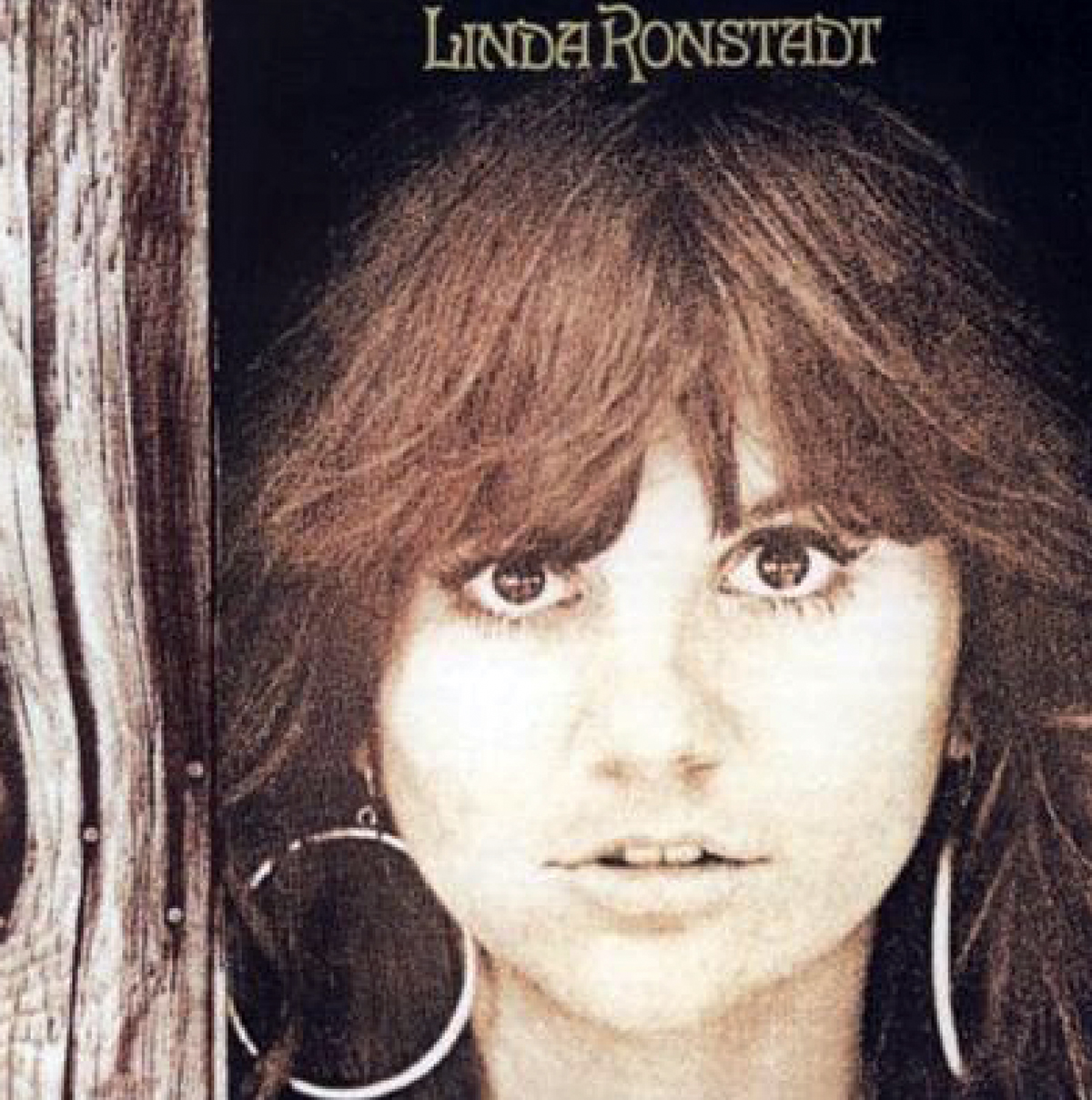

Linda Ronstadt’s first album

By January 1972, Linda Ronstadt was touring in support of her new album, simply titled Linda Ronstadt. Going solo in 1968, her early efforts were a mixture of folk, pop, and some memorable country rock, such as her classic rendition of “Silver Threads and Golden Needles.” Though never a songwriter, Ronstadt was a master of interpretation and delivery. In classic country-rock fashion, she included songs on her new album as diverse as such country standards as “I Fall to Pieces” and “Crazy Arms” to songs by long-haired firebrand Neil Young and relative newcomer Jackson Browne. This album launched Ronstadt into country rock stardom.

In 1968, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band left its jug band beginnings and reinvented itself as an innovative and formidable country rock outfit. With the 1968 release of Uncle Charlie and His Dog Teddy, the band took its place among the country-rock elite. In 1972 the group would release its landmark album Will the Circle Be Unbroken. Though Dylan connected himself to many in the Nashville establishment with Nashville Skyline, the Dirt Band closed the considerable gap between Nashville and the music of West Coast young guns with this new work. The album featured such hallowed country luminaries as Roy Acuff, Earl Scruggs, and Mother Maybelle Carter as well as many others. The album was embraced by young back-to-the-country commune dwellers as well as fans of the Grand Ole Opry. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band continues to be recognized for its musical excellence and longevity.

Just prior to the dissolution of the Chris Hillman-led Flying Burrito Brothers, Hillman and certain other band members happened upon a pretty, young girl singer, pouring out her heart to a sparse and disinterested audience in a Washington D.C. coffeehouse. The young singer was Emmylou Harris. Hillman connected her with Gram Parsons. Harris became Parson’s harmony singer and junior partner on his two legendary solo albums GP (1972) and the posthumous Grievous Angel (1974). Following Parsons’ death in 1973, Harris forged her own long-lasting and prestigious career, using Parson’s template for country rock.

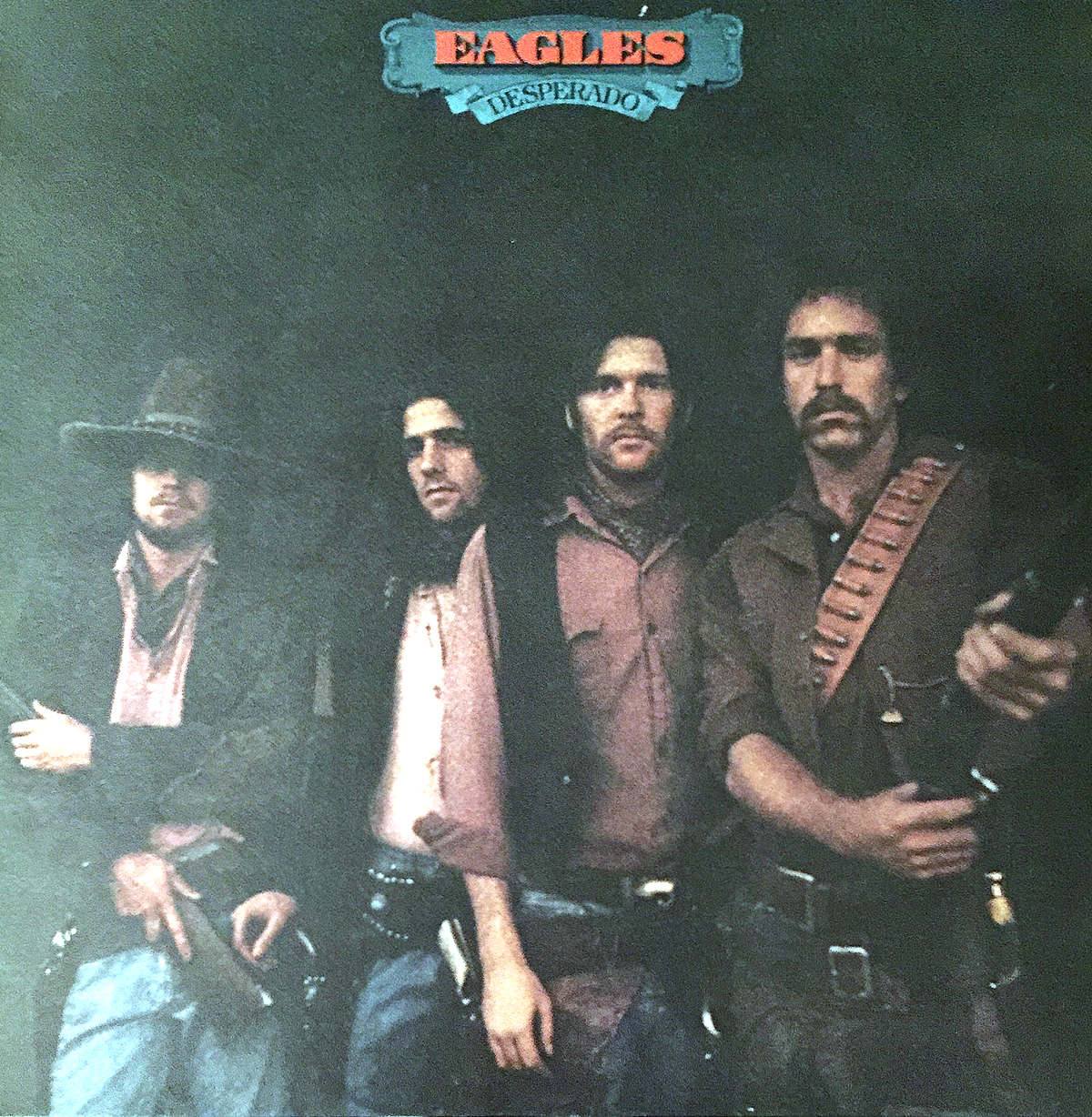

The Eagles’ classic album, Desperado

In 1972 the Eagles began their huge career with their debut album, Eagles. The original four brought together their considerable talents as players, singers, and tunesmiths and a wealth of experience with folk, rock, country, and bluegrass. Both Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner participated in the first country rock onslaught. Leadon was a member of Hearts and Flowers, a Dillard and Clark expedition player, and a Flying Burrito Brother. Meisner was a charter member of Poco and served in Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band. Don Henley came to California via Texas as drummer and singer for Shiloh, a southern-fried country-rock band. Glenn Frey served tenure with J.D. Souther in Longbranch Pennywhistle, an easy-listening soft-rock duo with country influence. The original Eagles comprised Linda Ronstadt’s crack back-up band at one point.The Eagles learned from the mistakes of their country-rock predecessors. To avoid the tag of being too rock for country and too country for rock, there would be no pedal steel guitar in the lineup. Leadon would approximate that sound with his string-bender “Tele.” With country-rock jewels like “Take It Easy” and “Peaceful Easy Feeling,” it was easy to peg the band as country rock, but the music on Eagles was a mix of various styles. Their eclectic blend appealed to a listening public that wanted more punch than that offered by the many mellow singer-songwriter acts of the day, while it also appealed to fans who felt alienated by the pretentious overstatement that much of rock had become.

When Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner departed, the Eagles lost much of its country-rock flavor. But country rock pushed ahead. Rodney Crowell and Ricky Skaggs emerged from Emmylou’s shadow to become young-gun legends themselves. The early ’80s saw the advent of “cow punk” outfits like the Long Ryders, Lone Justice, and Jason and the Scorchers. Dwight Yoakam had roots in that scene as well. From ’86 to ’90, country rock, California style, finally gained popular radio exposure. Though many of these groups and artists were not California based per se, their music was strongly influenced by the California country-rock sound. Highway 101, Rosanne Cash, Southern Pacific, Foster and Lloyd, Bailey and the Boys, and of course Chris Hillman’s Desert Rose Band were a few of the bands that represented this sound. Steve Earle, the ultimate rebel rocker, also hit the airwaves during this time.

By 1990, a counterfeit “country rock” began to replace the real McCoy. Many simply turned off their radios and abandoned this commercialized nonsense to the boot-scooting masses. The descent of country radio continues to this day. “Hunks,” “babes,” and the “show” now drive the bus, while quality and integrity take the back seat. Still, a parallel universe of great country music exists, sometimes referred to as “alternative country.” Whatever it’s called doesn’t really matter. Indeed, many of the genre’s pioneers hated the term “country rock” from the get go, due to its limitations in describing the content and format of the music. Perhaps it is better described the attitude and musical interpretation of the players. Today’s alternative country/country rock might have a classic western swing beat, a jazzy flare, a blue-collar Bakersfield edge, a Gen X angst, or a greasy rockabilly feel. Still, in all those incarnations, the legacy of California’s young guns rides on.

This article is a reprint from the March 2002 issue of the San Diego Troubadour, written by founding Troubadour member, the late great Lyle Duplessie. Lyle was an exceptional writer, gone way too soon. We miss him.