Featured Stories

Aly Rowell Is an American Dream

Aly Rowell

Mission Bay is the kind of place that tricks you into believing in peace. The water is calm, kids are biking in circles, the trees are making a half-hearted effort at shade. But the day I sit down with Aly Rowell on a bench overlooking the bay, the world is anything but calm. It’s less than 24 hours after the murder of Charlie Kirk. Everything feels tilted, like the sunlight itself is on edge.

The weight of the world is still sitting between us, thick and stubborn, the kind of heaviness that makes you want to scream into the sky. Or at least throw your phone across the room. Today, it feels almost absurd to even think about music. We acknowledge it. We are dizzy and maybe a little afraid of the implications. And yet, I lean in, grinning a little at the tension. “Okay,” I say, “if your life had a soundtrack right now, which three songs would be on it?” It’s silly, sure, but it works. Somehow, in a world that feels so fractured, asking someone what scores their life is the fastest way to get to the heart of who they really are. Aly laughs, her smile taking over her whole face, and just like that, we’re off, walking from the heaviness into something personal, human, alive.

“The Brilliance,” she answers immediately. “I grew up in the church world. So, they are kind of like Christian-adjacent. They wrote this song called “Facebook” and one thing I keep thinking about a lot lately is trying to figure out what’s real. There’s a line in the song that goes The man assumes that what he’s got/That what he’s got is called the truth/But can we ever know truth?/How can we ever know, when we assume?’ That is a theme in my life lately. This is a song that is hitting hard right now.”

She pauses only long enough to breathe, then keeps going.

“A song that will always be important for me is ‘Helplessness Blues’ by Robin Pecknold (Fleet Foxes.) I was raised up believing I was somehow unique, like a snowflake distinct among snowflakes, unique in each way it can be. But now after some thinking I say I’d rather be a functioning cog in some great machinery, serving something beyond me. I remember listening to that in high school, just thinking about my individual self and who I wanted to be. I grew up in an immigrant family in Orange County, so that’s a song that’s always been a bedrock for me.”

She laughs and shakes her head. “Also, a fun song I’ve been listening to lately is by an artist named Matt Maltese. He wrote this song called “Wedding Singer.” It’s a guy who wishes he could have a relationship but he’s just kind of an awful person. That’s kind of the range of what I listen to. I’m having an existential crisis at any given moment.”

Existential crises. The American Dream. The false promises of corporate America. It’s all sitting in the space between us, as casual as the breeze coming off the bay.

Aly & friends at Songwriter Sanctuary. Photo by Liz Abbott.

I ask her what lesson from her immigrant family still shows up in her music. She doesn’t hesitate. “My parents are very principled. They are not sell-outs. They are very ‘I believe what I believe.’ They’re convicted and not going to waiver on it. I think I am very much that person, too. When I believe something, I rarely retract. I make an effort to be very consistent in the person I am. We have had very interesting conversations, especially lately, where they have differing opinions than I do, but not waivering is something I for sure learned from them.”

There’s something beautiful about her defiance. She is integrity-driven without being rigid, convicted without being closed off. Aly doesn’t romanticize her own past. When I ask her about the songs she wrote when she was younger, she explodes into laughter.

“Oh, man. My parents do not come from a creative/music background. So, I grew up listening to bad Christian music, ’60s and ’70s rock and Mozart. It was an interesting combination.”

Here’s where it all collides. The math of Mozart, the manipulative chord progressions of Christian worship, and the messy honesty of folk songwriting. The science of how to stir a congregation. Psychologists call it musical emotional priming. Filter that through the ears of a “brown girl growing up in white spaces.” Add the prose of her journals and the unique experience of her Filipina immigrant household, and you’ve got Aly Rowell.

“I love people-watching and taking everything in and watching the crazy things people do, so when I look back at the songwriter I was when I was young, I just sit back and say, ‘Oh you silly girl.’ In my more lucid moments I’m like, ‘She really didn’t know anything!’”

She’s laughing again, her whole face lighting up. I can’t help but laugh too. I remember my own silly girl.

“How could she have known anything?” Aly asks, eyes sharp and alive. “There was no one there to tell her any better.”

And then the universe decides to make its own contribution to the conversation: a few loud and insistent June bugs come barreling toward us. Suddenly we’re running through the park, screaming and laughing, swatting at the air. We collapse under a tree in a clearing that seems safe enough.

We’re still laughing when I ask her about prose.

“When does a story demand to be a song instead of a poem?”

Aly sits with this question for a while. My eyes sometimes dart around to check for June bugs. “I think in the past up until my early 20s. I would just write prose. At that point for sure, I didn’t have anyone showing me how to make them into songs. I write a lot for myself. I journal and I just write. I pick from my journaling what I want to share. I think right now in my current form, a lot of what I write just happens to be songwriting. Especially existential stuff. It fits my niche as a songwriter. What is truth? If it hits the existential theme, then I know it’s a song.”

I start to ask if she’s building an album or a collection, but the universe interrupts again. One more uninvited June Bug sends our arms flailing. An acorn drops from a tree and smacks me on the head. Aly and I both lose it, laughing. What is happening?

The acorn’s unexpected strike had us both distracted once again, but it was time to pivot from flying projectiles to the music she was quietly crafting.

“My last album was reflecting on my twenties. I don’t know if it’s a conscious effort, but the record I’m writing now is about my family and generational trauma, and all my songs are sort of fitting into that niche. But all my songs sort of fit into a “why are we here?” category and processing that. It is an interesting thing. I wish I had this record when I was growing up.”

The more she spoke about her current record, the more obvious it became that this album was one part therapy, one part reparation. A hand-out to the silly girl who had dreams the world hadn’t made space for just yet.

Growing up in an immigrant family, Aly navigated a world where logic and stability often outweighed creativity. Her parents fostered her interests in art and music, but only within the structured confines of a church context. “If you like to sing you should do it in church. If you like art in any way, you should do it within a church context. And that’s not wrong, just to me it was an incomplete picture,” she explains. The unspoken expectation was clear: pursue a conventional path.

It wasn’t until after a job loss and encouragement from her husband that Aly felt ready to speak plainly about her ambitions. One conversation with her mother became a turning point. “‘Oh, so you’re not working a real job right now?’” her mom asked, trying to innocently piece together what Aly was doing with her life. The question stung, but it forced clarity. Three days later, they drove to Orange County for a conversation Aly had carefully prepared. She broke down, her parents alarmed at the emotional weight of what they assumed was bad news. But Aly finally said what had never been voiced: “‘I am a sensitive artist; this is who I am. I want to write forever, and I don’t give a shit about corporate America.’”

Her parents’ reaction was an unexpected revelation. “They told me they loved me and wanted to support me. It was game-changing for me.” Aly had just come out to her parents-as a creative. We giggle at the comparison, but the weight and fear of possible excommunication rings true. Now she could confidently step into her own American Dream.

“It’s so true! They had this vision that, okay, you’re going to go to college, get married, have kids, work your job, and live in suburbia.”

She pauses, and then almost whispers, “Right, but even as a kid I was like, ‘Can I not?’ I would have dreams as a child of living in New York City and writing a book or playing in an underground coffee shop. I never dreamt of corporate America. But they took it very well.”

The emotional gravity of her coming-out story brought us back to her new record. The record she was building was a tribute to her family, a reckoning with generational trauma and a reflection on what it means to grow up between cultures.

Her first EP leaned indie rock heavy, but this new record she describes as “orchestral, guitar, voices, strings.”

“I think I’m writing it for the brown girl who lives in a white context with people that she loves in this context, a beautiful community. But also, she feels different. And she watches her mom and women in her family engage in challenges and struggle and drama. I hope that if there’s any sort of resonance with people that it’s a niche experience set to nine songs.”

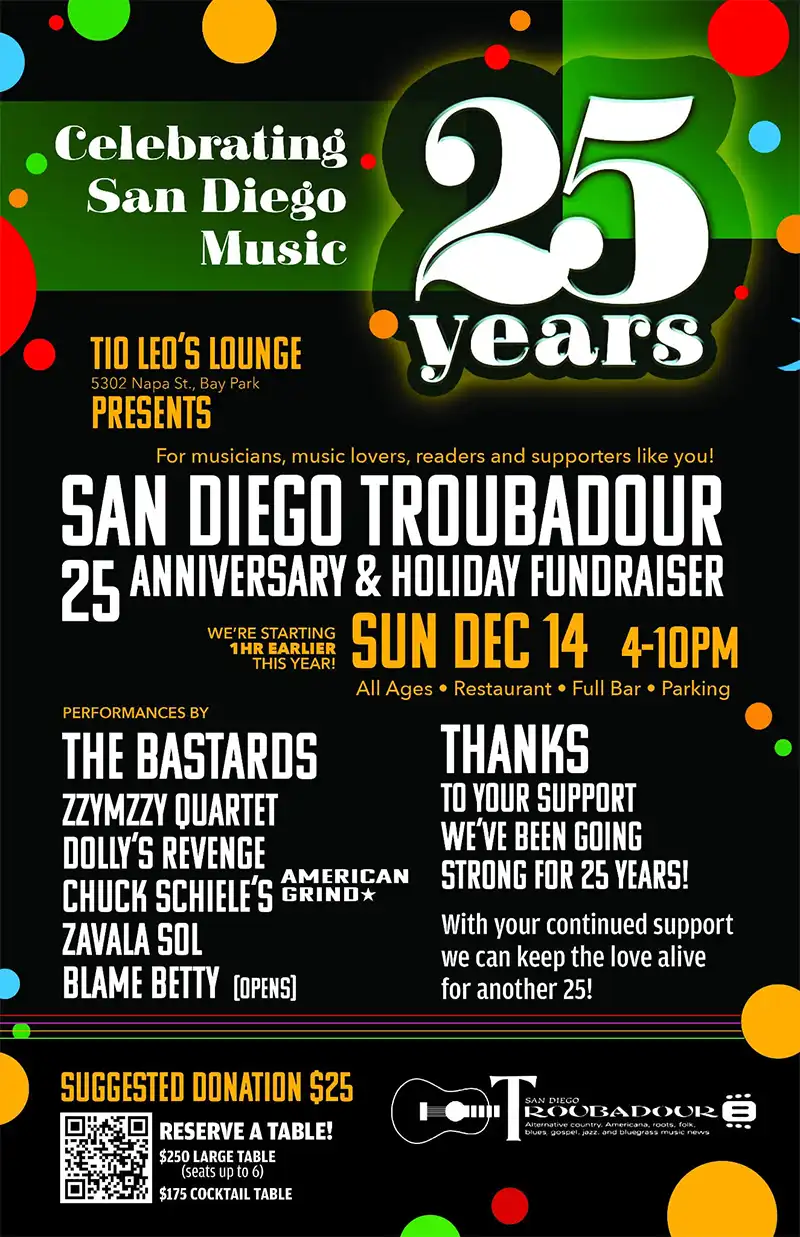

At the Casbah. Photo by Liz Abbott.

I can’t help but notice the care in her words. She’s building a bridge. Laying the bricks to connect the person she was and the community she inhabits now. “Yes,” she says, like she read my mind. “There’s a lot of great music out. But I turned to Nate [her husband] and said, ‘Everything is a vibe and a playlist. It’s everywhere in culture. Like Pinterest aesthetics. Everything is ‘everything-core.’ I think that has its place, but I think people are hungry for albums again.”

I find myself lamenting the death of the album experience, the way music is swiped and scrolled and consumed like fast food. How my 16-year-old son will never know the agony of waiting months or years for an album, waiting in line, finally getting it and the sacred ritual of locking yourself in a room and closing your eyes and diving into a full album. And Aly is enthusiastically agreeing with me.

In this moment, we feel like if people could just experience art the way we used to again, we could change the world. A thought that feels especially poignant considering the weight of everything when the divide in culture seems so raw. I turn to Aly, curious how her renewed faith informs her songwriting in a world that often feels so fractured.

“I think what I really do appreciate about certain corners of Christianity is there’s a part that’s very cerebral. There’s always been this existential thing for me. What is my given purpose? What is the afterlife? I struggled as a child with concepts of the rapture and things like that. I was legit worried I was going to be left behind. Long walks thinking about humanity and the reason we are all here. It’s kind of all I write about.”

There’s a literal honesty in the way she names the rapture and the childhood terror of missing an apocalypse that everyone else seems to be prepared for. It’s not melodrama: it’s the small, private obsessions/trauma that become art. That’s her scaffolding. The music keeps asking the same question. Why are we here? She repeats it so often that the repetition becomes a method.

Beyond songwriting, she’s working on a speculative novel about age and generational differences, and she pours her energy into nonprofit work that lifts others up through The Table Art Society. I love that about her. She runs cohorts, guides conversations using the Artists Way curriculum, and hosts events that mix musicians, poets, writers, and even tattoo artists. Pretty much anyone creating something worth noticing. Watching her talk about it, you can tell that it is personal and not just charity or resume-building. She’s giving other artists the support she wishes she’d had growing up, carving out a community where creativity, honesty, and conversation get to coexist without judgment.

But what grounds her? Her drive is there. Her ambition is there. Her passion is so clear. Her music is absolutely worthy of mega stardom. How does she not let it carry her away?

What grounds Aly is love. Her husband, her friends, her community. “Art is a byproduct of living. Hopefully, art is a symptom and a product of you living your life. Life should be the objective. At the end of your life, are you going to be hugging your Grammy? I would much rather have my community and genuinely support other artists. Let’s not lose our humanity in the process.”

When I ask what she hopes people will say about her 20 years from now, she doesn’t hesitate. “Not only is she talented, but she’s generous with her resources and she’s generous with who she is as a person.”

By the time we leave Mission Bay, I believe her. Aly Rowell is not chasing the American Dream. She’s rewriting it.