Featured Stories

The Mystic as Activist (or Vice Versa): Bruce Cockburn Is Still Looking for the Lions

Bruce Cockburn in 2018. Photo by Craig Silberman.

Bruce Cockburn is the guy who wondered where the lions were. Then he asked for a rocket launcher. That was almost 40 years ago. He’s done a great deal since then, but those two songs—as different as a cheery hello and a punch in the face—still define him for many. If you’ve followed Cockburn’s career more closely, you know that his personae as the bemused, inward-dwelling mystic and the angry transnational activist exist on an artistic spectrum where one informs the other. Among the singer-songwriters of his generation, Cockburn is an artist who slips between borders, avoids close affiliations, and keeps himself free to blend into another scene. He has always been more than the sum of his sometimes-clashing personae, making him seem both open-hearted and elusive at once.

A brief overview: Born in Ottawa, Ontario, Cockburn spent an apprenticeship with various Canadian rock bands before going solo and releasing his eponymous debut album in 1970. A string of mostly vocal/acoustic guitar-centered releases followed, with jazzier embellishments added by the mid-1970s. Mostly overlooked in the U.S. during this time, he suddenly broke through with the whimsical, Jamaican-accented Top 30 single “Wondering Where the Lions Are,” taken from his excellent 1979 LP Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. Critics made note of Cockburn’s Christian faith, though its impact on his songs was usually indirect. Rather than continue to release albums as a typical “sensitive singer-songwriter,” he made a hard left turn into political commentary in the early ’80s. Outrage at First World militarism and corporate greed spawned tunes like “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” “Lovers in a Dangerous Time,” and “Fascist Architecture.” Though he added synthesizers and other MTV-era touches, Cockburn remained an acoustic folkie at heart—his fluent and often dazzling guitar playing was always a highlight of his work. In the 1990s, he brought together his spiritual reflections and social justice concerns on a series of memorable albums, with Nothing but a Burning Light and The Charity of Night particularly standing out. Subsequent projects have found Cockburn adept at everything from spoken-word passages to evocative instrumentals, all bound together with a cool yet committed intelligence that seemed at once worldly wise and deeply humane.

Cockburn’s latest album, O Sun O Moon, is very much in his tradition of thoughtful commentary, spiritual yearning, and slightly rueful self-reflection. At 78 years old, the artist is working within his limits—arthritis has forced him to find new chords and otherwise modify his still-masterful guitar playing. If time has brought him physical challenges, it hasn’t narrowed his perspective or caused him to flinch in the face of mortality. “You’re limping like a three-legged canine/Backbone creaking like a cheap shoe,” he sings with droll languor as he considers the afterlife in “When You Arrive.” “To Keep the World We Know” (a collaboration with Inuit singer-songwriter Susan Aglukark) is a warning against imminent disaster very much in the tradition of Cockburn’s earlier protest pieces. The dominant mood here, though, is one of acceptance, redemption, and transcendent love. He finds a way to embrace “the pastor preaching shades of hate” and “the self-inflating head of state” in “Orders” without closing his eyes to their failings—or his own. He looks toward an ultimate interweaving of humanity’s clashing colors: “We’re all threads upon the loom/When the spirit walks in the room…”

One of the most interesting things about Cockburn is how his perspective about life and the role of artist changed as he grew older. As he tells it, the breakup of his first marriage and touring beyond North America forced him to mature out of folkie insularity and open his eyes to the harsher realities of the world. “On the very earliest albums I really sound like a kid from the’60s,” he told me in a recent phone interview. “I hear it in my voice as much as anything. I was inwardly focused then; I paid attention to the spiritual stuff, which seemed appropriate and still does, but I didn’t really understand people at all. I’ve come to understand a lot more about that as time has gone on, and I can hear the difference in the songs.”

Cockburn in 1970.

As he ventured out of his shell, Cockburn began to see himself as a kind of musical correspondent, reporting from scenes of conflict and suffering and bearing witness with a minimum of preachiness. A trip to Central America under the sponsorship of the charity Oxfam in the early ’80s particularly opened his eyes. Calling what he wrote “documentary poetics” rather than protest songs, he filled albums like Stealing Fire (1984) and World of Wonders (1986) with reportage from Chile, Germany, Italy, the Caribbean, and other locales. Through it all, he tried to be accurate rather than strident about the injustices he saw—a stance even harder to maintain today thanks to the stark political divisions of the moment.

“I think the challenge is to find a non-polarized point of view from which to view it all,” he says. “That point of view is available to everybody, but it can be a little tricky to get there, because we all feel the emotional impact of the stuff that’s around us. It requires a certain intellectual rigor—if your own spirit doesn’t get you through, then your brain has to do so. I think it shows up in some of the new songs, like ‘Orders,’ which comments on the current goings-on from a position of not judging or at least not confronting in a hostile way. Hopefully, a lot of people are going to be doing that, because otherwise, we’re in a lot of trouble, even more than we’re in now.”

There are some pieces of musical reportage that Cockburn would file differently today. “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” was composed after he toured a Guatemalan refuge camp in Mexico. Its lyrics were written from the viewpoint of a displaced victim of government terrorism—but listeners have sometimes taken it as a personal statement by the artist. “That song has been greatly misunderstood by many people,” he says. “It’s the kind of song I would only write once—it came out of sharing the time and space with people whose life experience is totally different from mine. I would be very hesitant to risk being misunderstood that way again. I didn’t write it to incite people to shoot Guatemalan soldiers. It was more of a cry of horror at how easy it is to get into that mindset. With that mindset all over the place right now, everybody knows how easy it is and they don’t need me to help them.”

(In 2009, Cockburn performed “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” in Afghanistan, where his brother John was stationed with Canadian troops. The commanding officer presented Bruce with a rocket launcher, which he chose not to keep.)

Bruce Cockburn on Austin City Limits.

Cockburn’s particular take on Christian faith has likewise caused some confusion over the decades. His beliefs always had a mystical tinge that emphasized spiritual joy rather than sectarian dogma. When his music became better known in the U.S., he made his contempt for right-wing Moral Majority preachers like Jerry Falwell clear. Always open to insights gleaned from other faiths, he gradually drifted away from church attendance. Though spiritual references never disappeared from his songwriting, O Sun O Moon reflects a renewed interest in Christian worship with fellow believers.

After moving from Ontario to Northern California with his wife and young daughter in 2009, Cockburn began attending the San Francisco Lighthouse, a non-denominational Protestant church whose inclusive message resonated with his own outlook: “I hadn’t gone to church in decades, but I was led to this church and to a renewed focus on the spiritual realm. It partly has to do with age—the approach of that horizon is something you can’t ignore.”

Intimations of mortality are found throughout O Sun O Moon, offered with a mixture of awe, acceptance, and wry humor. Particularly haunting along these lines is “Colin Went Down to the Water,” a hymn-like tune inspired by a tragic incident: “It’s about a friend of mine. We’d made plans to get together in Maui. I phoned him when I arrived—it was Wednesday, and we were going to meet for a drink the next Monday. On Saturday, I got a call from a mutual acquaintance. He told me that Colin had drowned in a scuba diving accident. I went back and listened to a voicemail he’d left me: ‘Hello, Bruce, this is Colin. Welcome to heaven!’ He wasn’t a close friend, but he was a good guy and hearing that was strange and moving.”

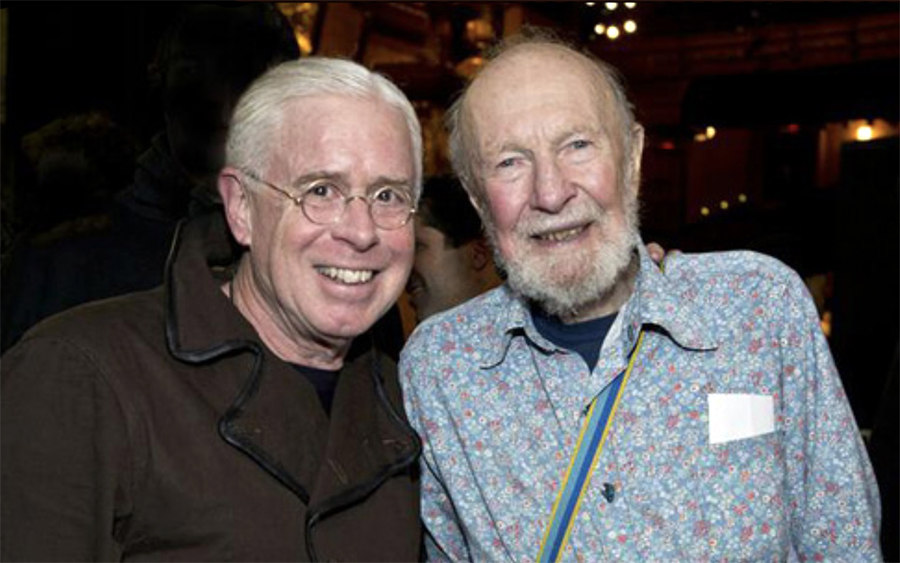

Cockburn with Pete Seeger, 2012.

Cockburn embraces his status as a musical elder with grace and a definite ocular twinkle. These days, he sports a long snowy-white patriarchal beard worthy of Father Time (or David Letterman). At a June 2023 solo acoustic concert in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, he came on stage with the aid of two canes and remained seated during his set. As fans shouted out requests, he explained that there were certain songs his arthritis kept him from playing, “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” among them. That noted, Cockburn more than acquitted himself on guitar during a set that featured tunes from his earliest albums as well as his most recent work. Switching from six- and 12-string guitars to dulcimer and dobro, he moved easily among the eras and phases of his complex and sometimes paradoxical career. Reaching back to one of his earliest LPs, he sang “Everywhere I go, the blues got the world by the balls,” lyrics that seemed accurate when he first recorded them in 1973 and are probably even more so today.

If not closure, Cockburn seemed to be finding unity in the disparate phases of a half-century’s worth of music-making, looking forward and glancing back simultaneously. When we spoke, I asked him if there was something he might say to the Bruce Cockburn of 1970. “Don’t be so fearful,” he quickly replied. “I would say that a lot of the stuff you think is really important doesn’t matter that much.” This led to advice for beginner artists: “Keep your integrity. You can entertain people and be truthful. You can say, ‘I’m going to write a song that rhymes with whatever so I can have a hit’ and that might work, but it won’t work for you for long.”

Bruce Cockburn has made his unique blend of heavenly aspirations and gritty poetic reportage work rather well for over 50 years. Between the lions and the rocket launchers and beyond, he has covered a lot of ground as well as considerable inner space. He remains a traveler between worlds and a messenger who speaks multiple spiritual languages. “With songwriting and performing, there’s that leap where you hope you’re giving people something that suits them,” he says. “I’ve been doing it long enough that you’d think I would have got it by now. But you never quite get it. There’s always something to learn.”

Bruce Cockburn will be performing at McCabe’s Guitar Shop, 3101 Pico Blvd., Santa Monica on November 17, 2023.