Cover Story

Joshua White Embraces a Radical Openness

Engaging in conversation with piano colossus Joshua White is somewhat akin to experiencing one of his live performances. There will be a natural, if unpredictable arc, it will behoove and reward the witness to pay close attention at all points. It can careen from one topic to the next, but it will highlight a unifying mosaic of intellectual curiosity, profound understanding of tradition, and an exhilarating sense of freedom. Like most opportunities in life–it is helpful to jettison your expectations and embrace the moment.

One of the qualities I cherish most in an improvising musician (Mr. White avoids the term “jazz,”) is audacity–that sense of disbelief that can make the listener laugh out loud, marveling over a defiance of expectation. All of the great pioneers of the African—American musical tradition exemplified this attribute. I don’t know what else to call it besides genius, and Joshua exudes that quality at every turn.

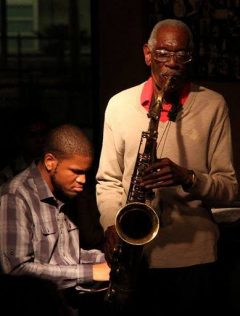

I’ve been following his career very closely for the past eight years since I first caught him playing in a ground-breaking quintet organized by the contrabass giant Mark Dresser in 2010. Even at the age of 24, White was already transcending the standard piano virtuoso paradigm–his ideas literally exploded off his fingertips and into the ether, and yet he never seemed preoccupied by technique.

Great music is shaped by superhuman listening and White is capable of listening at the absolute highest level. This is also manifested in conversation where he can seemingly answer a question before it is asked, an unnerving talent that nearly had me convinced he had stolen an advance peek at my notebook.

Since that evening eight years ago, my personal appreciation for his musicianship has grown exponentially. I recognized that here was a real opportunity to bear witness to a genuine phenomenon in the making. Over the years, I’ve made it a point to catch as many Joshua White performances as possible. He’s one of the few cats you could see three or four times in a given week and still come away with a sense of surprise.

It didn’t take long until I came to the realization that he is my favorite pianist. To place that statement into proper context, let me just say this: I spent many years enthralled by McCoy Tyner. After McCoy, Keith Jarrett was my man, and after Keith, Cecil Taylor.

And now it is Joshua.

Part of my enthusiasm is no doubt due to his amazing versatility. Joshua can conjure images that range from the powerful dissonant clusters of Mr. Taylor to the unbridled swing component of Bud Powell. He will go from a rollicking dissertation on stride piano straight into a rapturous distillation of the Baptist church, and he might do all of these things over the course of one solo. I’ve never heard anyone do that with such authority and I’ve been immersed in this music for more than 40 years.

How he got here…

Joshua was born in Los Angeles (Compton, to be exact) to Richard and Eleanor White, from Kingston, Jamaica and Charleston, South Carolina, respectively. “My family moved to San Diego when I was six or seven, right around 1990,” White remembers. “My dad’s job transferred from Los Angeles to San Ysidro, and they subsequently found a house in El Cajon.”

Growing up as a black kid in a predominantly white neighborhood posed a few challenges. “When you’re young you try to make friends and to be accepted, but it’s hard not to notice that there are only two other African—American kids at school and that you have interests that deviate from those of your classmates.”

In other words, the “welcome mat” had a few tattered corners and frayed edges. “We were actually turned away when my parents tried to register me in elementary school, because the administration didn’t believe that we lived in the district. They had to bring in paperwork and bills to prove we weren’t trying to scam the system.”

His parents always sought to provide him with a more culturally diverse upbringing. “They made a conscious effort to expose me to other influences, which is why I also grew up attending the Baptist Church in Encanto. They wanted to make sure I had a more balanced and well-rounded experience.”

Even discovering that institution involved some trial and error, according to White. “I think my folks found the church by just driving around on a Sunday morning until they saw a car full of black people who looked like they might be going! There was no internet back then, no Google, so they just followed this car.”

The church was one thing, but school was another. “On the playground, you might hear things like ‘nigger,’ and this one kid used to harass me with questions like ‘why are you black?’ The fact that he framed it as a question puzzled me at the time. I just thought of myself as a human being, but all of sudden my skin color meant that I was different to my classmates. Not who I was as a person–just the color of my skin.”

Always surrounded by music…

“Around the same time, I was developing musically,” says White. “And I had access to something other students didn’t have, which made it easier to ignore the lack of acceptance.”

He does not remember a time in his life where music didn’t play a huge role. “I’ve always been immersed in music. Back when we still lived in Compton I remember being surrounded by tapes and music videos by people like Queen Latifah and Miki Howard. And I grew up in the church. My mom was taking me to choir rehearsals even before I was born, I can’t help but believe that seeped in. Plus my dad had a love for music–he was a deejay back in his day with a large reggae collection. My folks listened to every choir you could think of, so that’s all a part of my experience.”

Once the youngster came to San Diego, that musical connection deepened when he discovered the family piano. “My mom and my sister had both been taking lessons and they noticed I had an interest so they took me to the Music School in El Cajon, where I subsequently met my first and, really, only piano teacher, Jennifer Martin. I took lessons from her every week for about ten years. She was classically trained, so that is what we studied, but at the same time, growing up in the black church, I got heavily involved in that music. I would sit in the first row and watch Sister Barbara Conley play every week. So all of those experiences–the formal training and the listening to people in the church had an influence on who I became musically.”

The roots of Joshua’s deep listening and communication skills can be traced back to those formative years. “In gospel music you are trying to convey a feeling, so you have to watch and observe to understand how to do that. You develop as an improviser in that context. By the 5th or 6th grade, I was playing for all the choirs every Sunday. I was carrying around a big bag of sheet music to learn the tunes until I gradually developed my ear to figure things out. Sometimes I would bring pieces from the church into my classical teacher and she would show me how to analyze things from that standpoint, and how there were similarities between gospel music and Beethoven, for instance.”

Slowly but surely music was becoming the driving force in the young man’s life. “I really lucked out with that teacher, she saw that I had a real interest and she gave freely of her time. When I broke my little finger playing flag football in middle school, I couldn’t play the piano for a while, so we worked on college-level theory breaking down Bach fugues to see how they were constructed while I recovered.”

And it wasn’t just the piano upon which White’s musicality manifested itself. “When I was in high school, I was a part of the music program. I played flute and piccolo and I also played written music in the stage band. At the same time I was doing classical competitions on the piano and I became section leader of the flutes in the marching and concert bands. I even became drum major in the All State and District Honor bands. When I was still in high school, I was playing in the Grossmont and San Diego State Symphony Orchestras.”

“Joshua is a true original thinker. A gem. He does things his own way, digs deep, and cares intensely for the music and its future. When something fascinates him, he will investigate to the greatest possibility, whether it’s an author, a composer, or anything else. In his music you can hear his sensitivity, his power, his generosity, his virtuosity.” –Nicole Mitchell, flute

Jazz came knocking…

In 2003 as high school was winding down, White was primed for a new musical challenge, and he found one in La Jolla. “I looking for an interesting program after I graduated and UCSD was just starting their Jazz Camp, so I went there the first year they opened. I met everyone on the faculty–(trumpeter) Wadada Leo Smith was there, (pianist) Mike Wofford, (flutist) Holly Hofmann, (bassist) Rob Thorsen, (trumpeter) Gilbert Castellanos, (drummers) Gerry Hemingway and Jeff Hamilton, and (pianists) Eric Reed and Anthony Davis. All of the cats you know?”

It is worth noting that White has played professionally with almost every one of this stellar cast of mentors in the intervening years, both as a sideman and leader. Even though, or perhaps especially because, he had no background in the idiom, and could have been intimidated, an important die was cast that first summer that resonates to this day.

“That singular experience opened me up–because I was coming in there fresh–I didn’t have an understanding of Miles or Coltrane or any of that. But I’m naturally a sponge–put me in any environment and I’m going to listen and absorb everything. It was a whole new world for me and I liked it enough to come back three years in a row. It opened up a creative voice in me that I had never really explored before. The first two years I attended playing both flute and piano, but by the third year, I decided to concentrate on the piano. My creative voice really derives from the piano, that’s what comes most naturally to me–it’s the most direct mode of expression for me.”

So, has he ever missed playing the instrument? “Every once in a while, I’ll think about going to a pawn shop and picking up a flute, just to be in that environment again, maybe to play some chamber music–or play some orchestral parts to be immersed in that experience.”

“Joshua White is a phenomenal pianist! As an improviser he has the ability to articulate and creatively respond to anything he hears and feels in real time. Even though he can access the whole history of the music through his breadth as a pianist and his unerring ear for sound, including pitch, harmony and rhythm, they are in service to an original artistic impulse to abstract and create meaningful new musical narratives.” –Mark Dresser, bass

Becoming Joshua White

“After Jazz Camp, I did get a scholarship on flute, mind you, to attend Long Beach State, but I ended up going to Grossmont College where I met (trumpeter and instructor) Derek Cannon. He would encourage me to check out recordings and I took that advice very seriously. I would say that my biggest musical influence was Tower Records. I didn’t just check all these records out–I would listen to them incessantly and I would memorize every aspect of those records. That was my form of study. I didn’t listen to anything else. One thing led to another. I’d find a Miles Davis record, look at the personnel, and try to check out every record that they played on. I became obsessive. To this day, you can play me a record and I could tell you who it is, who is on it, when and where it was recorded.”

That obsessive devotion to detail led White into memorizing hundreds of pieces from the Great American Songbook. “In that way, I learned as many tunes as I possibly could, and I placed my emphasis on memorizing them as opposed to reading them. Then I started going out everywhere just to listen to the cats playing, like Gilbert Castellanos, and any tune he played that I didn’t know was a tune I needed to learn in case I was ever called upon to play it. Or, for instance, I would go hear Charles McPherson and he would call ‘But Beautiful,’ a gorgeous ballad, quite frequently. I thought to myself I should know that in case I get the chance to play with him. And lo and behold, I played with him later and he called that tune.”

His method for learning standards has evolved over the years. “Now I learn vocal tunes by listening a lot to Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Nat “King” Cole, and Blossom Dearie. I learn the lyrics, which automatically gives me the melody, and if I know the melody, I know where it lies within the chord structure and I know where the bass notes are. If I know all of that, I have a pretty good grasp of the form, so even if I’ve never played the tune, if someone calls it… I know that tune. If I can hear it in my head, I know it.”

Of course, not all music is achieved so effortlessly. “A humbling experience is when I get a new piece from Mark Dresser,” confesses White. “He lets me find my way, because some of that music is hard. Now, I see everything through the lens of improviser, even my own music. What’s on the page is just a guide, I tell the people in my bands to play whatever notes they feel they need to play to deliver the message.”

In 2015, White got the opportunity to play with East Coast saxophonist Greg Osby, whose music he had admired for years. “I already knew what tunes he wanted to play. Even though I had never written them out, they were already in my brain. I had been listening to that music for years, so it was like I had been there before. Seeing the charts was almost unnecessary.”

Breaking out with Rudresh Mahanthappa

New York-based reed man Rudresh Mahanthappa was on top of the jazz world in 2015, winning three different categories in the Downbeat Magazine Critics Poll Awards, including Best Album for his record Bird Calls; Best Alto Saxophone, and Rising Star Composer.

His visage graced the cover of all the jazz magazines and when he realized he needed a pianist to fill the chair of Matt Mitchell, who originally played on Bird Calls for a tour of Europe, he took a chance and decided to hire White without having actually heard him play, based on strong recommendations from among others, Mark Dresser.

“It was a wonderful experience,” says White. “And it was definitely an honor that he contacted me for that tour, especially since we had never met. He hadn’t heard me perform, so he was certainly taking a chance. It was such an opportunity and we had some fantastic performances.”

Once again, White’s ability to adapt and perform under pressure proved invaluable. “Even though I was new to the band, and the music was quite challenging, I feel that is where I can thrive the most. At our first gig, I was meeting cats I never met, playing music I’d never played, performing in a country I’d never seen, in a major festival in Serbia. I had the choice to go all the way in, or lay back, and I chose to go all the way in!”

“It wasn’t like it was some little gig. It was the Belgrade Jazz Festival and there were hundreds of people in the concert hall. We had never heard him play. But he showed up and kicked ass, no doubt about it. The audience was stunned, like ‘who-is-this-guy?’ To be honest, we were thinking the same thing, I think it was a different experience for him to play with a band that did 20 gigs in a row. We did two tours and I’d love to work with him again.” –Rudresh Mahanthappa, saxophone

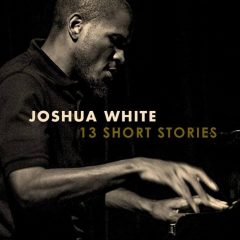

13 Short Stories

Last October, White released his debut album on the independent Spanish record label Fresh Sound New Talent, a wide-ranging epic that alternates solo piano tracks with a hand-picked quartet featuring saxophonist Josh Johnson, bassist Dean Hulett, and drummer Jonathan Pinson. The music flows from the volcanic to the pensive and serves as a wonderful introduction to his music for the hitherto uninitiated.

Like many of the milestones in White’s career, (including a stunning second-place finish in the 2011 Thelonious Monk piano competition in Washington D.C., where he met then-President Obama) he remains low-key about this latest achievement. “Personally, I don’t feel any differently, because really, it’s just a snapshot of what we did on a particular day. But it does mean something to other people, the fact that I have a record out. To me, it’s just another aspect of being in the music business. What I value most is the learning experience. I want to become better informed for the future. That will impact who I am as a person and how I develop as an artist.”

He already has a vision of the follow-up. “I was just in contact with the record label about recording a new album that is still in the planning stages. Also I have a duo project with the great bassist Marshall Hawkins, which should be coming out this year. I’m still looking and experimenting with what it is I want to express next.”

“Joshua’s musicianship is totally off the chart. He has astonishing technical fluency on his instrument, and he can hear and respond to incredibly complex pitch and rhythm information in real time. But what I really love about playing with Joshua is that he isn’t focused on dazzling you with his skills, but instead uses them to seek deeper kinds of interactivity, expression and invention. He always surprises me in the moment of performance with his imaginative choices–I never know what’s coming next, but somehow it always makes sense and opens up a new possibility within the music.” –Michael Dessen, trombone

The art of the solo piano concert

For many years, some of the most exciting moments of every Joshua White concert occur when the band stands down and he commences to redefine the conceptual geography of solo piano. Oftentimes, he deconstructs a well-known standard–stripping it bare and reorganizing its vital information in a Cubist fashion–rendering the familiar into utter abstraction before allowing strains to reformulate back into a tune that attentive listeners can follow.

He’s done that before with Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” and John Coltrane’s “Lonnie’s Lament,” and it’s common to discover people in the audience who felt transformed by the experience.

This year, White has been gravitating more often to the solo concert aesthetic with a series of performances held at Dizzy’s in Pacific Beach, ostensibly celebrating the music of notable performers like Mary Lou Williams, Mark Dresser, Geri Allen, and Herbie Hancock.

“Although I love playing in the context of groups, I find that even in the best situations, there is always a limitation to what you can reach creatively,” the pianist revealed. “Because of the democratic aspect of playing in an ensemble, I can’t always follow any direction that comes to mind. So I’m excited about pursuing more solo opportunities and developing that platform.”

But don’t come in hopes of hearing a typical “tribute” concert. “I’m using other composers like Williams or Dresser as a jumping-off point to explore their music as a vehicle for self-expression. But I’m trying to draw my own portrait of these people through my research of their music. I want to share how I think and how I interpret by using the concept of a familiar melody that doesn’t belong to me.

Sometimes being a prism for all that shines around you sonically has its own price tag, and that can be quite brutal. Lately, White has intentionally avoided listening to music because it has reached a point where it has become pervasive. “Earlier, when we were talking about listening incessantly and really absorbing everything–it has occurred to me that at some point that might turn into a negative. After a while, even if I haven’t heard someone or something… I already know where they’re going. I don’t want to put this on anybody else, because it’s my issue, but I became frustrated with the whole idea of form, the idea of melody, the idea of harmony. My frustration is with myself, so I thought that maybe I should concentrate more on solo playing until I can develop at my own time in my own space. What if I want to play just half of a melody–or just chords–or just one note? Playing solo allows me the opportunity to work those things out.”

The importance of literature as inspiration

White has always been a voracious reader. He carries books with him everywhere and often seems to be reading a half-dozen at a time. His quest for knowledge in a slew of different disciplines is not easily quenched, and it has a direct effect on his playing.

“In place of music, literature has been my focus. Music got to be too technical, so for me to be creative, I had to seek inspiration from somewhere else, and that somewhere has been the world of literature, which allows me to approach music from a different creative angle. Without that, hearing music becomes an almost robotic, automatic type of thing.

“Ultimately as an improviser, it’s great to have technical facility and all of that, but you have to remember that you are in pursuit of an idea. That’s what all the practice is all about: to express an idea. So the larger question is where do these ideas come from? How do you cultivate them? I need input to force my mind to visualize creatively, and I believe that is what literature has done for me, whether it is from the driest scientific text to fiction, poetry, philosophy, biography or whatever, I believe that reading necessitates a high capacity to visualize.”

When White gets a break at Gilbert Castellanos’s weekly jam session, he often retreats to a quiet corner to catch up on a few books. Don’t be surprised if he doesn’t notice you, however. “When I’m reading, I can block out anything. I read constantly when I’m at the gym, and nothing bothers me or breaks my concentration–not noise or music or people talking. I’m able to tune everything out and really work on thinking and formulating questions about what I’m reading and that’s how I stay engaged.”

Final thoughts…

I had to ask White if he could imagine pursuing a different profession other than music, perhaps a career in academia, given his protean interests. “Is there something else I could do for money that would keep me fulfilled? If I’m being honest with myself, I’d have to say the answer is no. But I do find the pursuit of intellectual enrichment and education and the struggle for balance between music and the engagement of the world of ideas is fulfilling and as long as I have that in whatever I do, I’ll be able to survive. I’ll be able to manage. Music is an incredibly difficult way of making a living–so if I can maintain that balance within myself, I’ll be okay.”

Chick Corea once characterized the avant-garde as folks who had “painted themselves into a corner.” I wondered if he had ever gotten so “far out” that he could not find his way back? “There’s always a way out of any situation,” he answered. “You are only limited by your imagination, but truth be told, I don’t want to be in a situation where I already know the way out. I want to be in a difficult situation. I want to have a challenge, because it puts demands on my creativity–because there’s always a solution–if you are in a space to see that. I try to paint myself into a corner, because there is no corner! The corner only exists in your head, and I always try to see beyond that limitation.”