Bay Area pianist and composer Todd Cochran has roamed far afield in his five-decade career, from writing cinematic scores to producing R&B artists, playing everything from progressive rock to New Age. While his studies were in classical music, he began his professional career in jazz, playing in a quintet with Bobby Hutcherson and former San Diegan Harold Land in 1971. Later in the decade, he played with the likes of Herbie Hancock and Julian Priester.

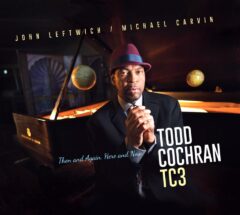

His latest release, Then and Again, Here and Now, finds him back in a jazz setting, fronting a trio with San Diego County product John Leftwich on bass and Michael Carvin on drums.

From the opening double bass lines of the first track, “Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise,” it’s clear that Cochran views this as an ensemble outing. While it’s Cochran’s name on the album, and his piano is center stage, both Leftwich and Carvin also receive plentiful opportunities to solo throughout the 15 tracks found here. And when not soloing, their playing is never passive, but weaves into Cochran’s lead.

Leftwich is featured in two short (minute and a half) solo “interstitials” of his own composition. On these pieces, Leftwich reminds a bit of Rob Wasserman’s classic 1983 solo-bass outing in tackling melodic leads with a highly syncopated approach, somehow playing melody and rhythm all at the same time, sacrificing neither.

Leftwich, who grew up in Del Mar and was part of Peter Sprague’s Dance of the Universe ensemble in the 1970s, is hardly the first San Diego product Cochran has collaborated with. In the early ’70s, Cochran composed and arranged Bobby Hutcherson’s highly regarded Head On album, which featured tenorman Harold Land.

This set is mostly a straight-ahead, although the trio does veer into a classical vein when they tackle a Bach prelude. But on “April in Paris,” Cochran leads the trio through a reading that is intense in its emotionality as it is relaxed in its time signature. In taking this approach to a well-known chestnut of a song, they manage to rediscover new sides and colors to it. Yes, it’s the same song Basie made a flag-waving chart-topper—but it’s something entirely different as well.

While Cochran contributes the title track and co-wrote “Verselet for the Duke,” the rest of the songs are covers, mostly well-known (“I Got Rhythm,” “Don’t Get Around Much Any More,” “Bemsha Swing”), while others are forgotten gems, like Bobby Hutcherson’s “Little B’s Poem” or Dave Brubeck’s “The Duke.”

Throughout, the combination of Cochran’s distinctive piano and Leftwich’s signature bass lines provide a new illumination for even the standards. It’s like seeing a photograph of a famous actress lit from a different angle, bringing out textures and contours previously unnoticed.

Cochran’s approach to the keys here is wholly mainstream jazz—you’d never guess he spent years recording for Windham Hill or toured with Carl Palmer. Listening to this album, it doesn’t seem he has a dominant hand – his left-hand’s bass lines are as distinct and prominent as what his right hand is doing in the higher registers.

Leftwich is a prodigously literate bass player—able to tease the melody while providing both harmony and aiding Carvin in providing the rhythmic foundation. Even when not soloing, he seems to always be improvising—always introducing some interesting thread into his playing.

Carvin is equally imaginative—he’ll drop out of the mix for a few bars, then come back in so organically it takes you a second to realize he wasn’t playing earlier, and it’s as if he never stepped back. Utterly seamless.

It all comes together in a beguiling cover of Thelonious Monk’s “Bemsha Swing,” a song so idiosyncratic that sometimes it seems only Monk’s many versions really make sense of it.

While many artists avoid comparisons to Monk and try to reinvent the song, Cochran, Leftwich, and Carvin come at it straight from the Monk playbook: Syncopated, stuttering. Cochran opens it comping quietly, then Leftwich starts noodling bent notes on bass shortly before Carvin starts in. Cochran then starts in on broken scales and block chords, before tinkling out an extrapolation of the theme. About two-thirds of the way through, Leftwich breaks out his bow, and first echoes Cochran’s reading, then takes it into further orbit, with Cochran backing him on piano.

One can listen to this version of “Bemsha Swing” a dozen times or more and hear something new every single time—it’s that good.

The interplay is of a similarly inspired level on nearly every track, jazz fans can only hope that this trio returns to the recording studio before too long. It would seem a most productive and rewarding combination of talents and personalities.