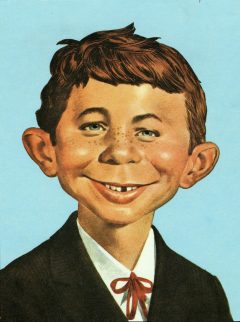

Mad magazine mascot, Alfred E. Neuman.

I remember the time when I was with my family on one of our regular Saturday morning shopping sprees at Kroger, enjoying the air-conditioned consumerism among the long lanes of plastic and plenty.

Standing in the checkout aisle, my older brother grabbed a magazine and implored my parents to splurge on the 30 cents for the publication. On the way home my brother unusually and generously allowed me to glance at his new treasure.

On the cover was a redheaded kid. His hair, haphazardly clipped, went this way and that. His ears flew out from his head, and his eyes were too far apart and pleasantly sleepy. And there was the grin with the lost tooth. It all spelled stupid, yet somehow in my nine-year-old mind I still got it that this kid, Alfred E. Neuman, was also clued in. In school, he would have been grouped in with the slow learners. All the teachers and parents would have thought him a zero, but he would have also been the kid who knew how to get the illegal firecrackers and knew where his father hid his Playboy magazines.

From that very first issue of Mad, I fell in love with the silliness, absurdity, and surrealism of Don Martin. His characters, self-assured and clueless, endured Martin’s broad slapstick. And there was the rococo slapstick of Spy vs. Spy. Spoofs of TV shows like Star Trek and movies such as True Grit mocked fame, entertainment, and all the overused tropes of Hollywood. It took me a few issues, but I finally noticed and treasured the marginal humor, the cartoons, and gags that were stuck between illustrations and at the pages’ edges that sometimes proved to be the best stuff in the magazine.

But Mad gave me more than just silliness and laughs. Mad magazine was mildly subversive, and it gave me one of the greatest intellectual gifts that anyone can achieve in this world: cynicism. Until then my experience with comics had been confined to the highly bifurcated moral order of DC Comics, where the muscles and upstanding manhood of Superman and Batman dealt Truth, Justice, and the American Way on the degenerate criminality of Lex Lothar, the Joker and the Riddler.

It can be easy to dismiss the moral clarity of DC as being just kid stuff. But I found the same certitude in my parents’ magazines. In the pages of Life magazine Kennedy was a hero, the U.S.A. had fought the fascists and Nazis and was now fighting the communists in Viet-Nam, and all of the astronauts were faultless American Heroes.

Mad magazine made fun of astronauts. Mad showed me that teachers, politicians, movie stars, and even astronauts were faulted, that the powerful, famous, and influential were not really what they had portrayed themselves to be. Even the motivations of your most beloved heroes were often cover-ups for laziness, vanity, and greed. And everybody is stupid, at least from time to time.

The Bible taught me that the race is not always to the swift nor the battle to the mighty. Don Martin’s floppy-footed fools taught me that the list of losers can also include experts and authorities, as well as the smart and sophisticated. Neither of the sharp-nosed spies was the good guy nor the bad guy. Either one could have had a U.S. or U.S.S.R. insignia. Their antagonism, as well as their bond, were generated by their mutual guile. The insight wasn’t deep, but it was brazen and funny.

Advertising was dropped from Mad in 1957 (a practice held until 2001), which gave it the freedom to ridicule the ads found in the pages of other magazines, the ones that were respected publications. Through its ridicule, Mad’s message was clear. People will lie to you just to make a dollar.

By the time I made it to high school, I had tired of the sameness of Mad’s humor. I graduated to reading National Lampoon, where the jokes were even edgier. Mad might poke fun at Ted Kennedy; National Lampoon made jokes about Chappaquiddick. Also the adolescent finger pointing was tempered in National Lampoon. If Mad taught me that those in authority were faulted, National Lampoon taught me that among the vain, shortsighted, greedy, and superficial, I could include myself.

Mad recently announced that it will stop publishing new material and only print up archival material with new covers. All that satire and silliness is now kaput. Perhaps Mad’s relevance passed away a long time ago. Recently, when Trump compared Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg to Alfred E. Neuman, the cherubic 37-year-old confessed that he had to google Neuman to find out what sort of insult Trump was hurling his way.

It would be facile to blame the demise of Mad to the era of Trump; after all, how can you make a joke about a president who is a joke? How can you ridicule that which is already ridiculous? It might also be easy to complain that Mad is a victim of the political correctness police, that nowadays you can’t make a joke without offending a lot of people. But Mad has succumbed to the same forces that have ended other print publications, mostly television, and, more recently, the distraction of the internet and texts.

Rather than bemoan its demise, I’m celebrating Mad’s longevity. When Mad first hit the news racks in 1952, comics and magazines were plentiful and widely read. Then came I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners. Collier’s magazine stopped publishing in 1957. Look magazine ended publication in 1971, and Life stopped being a weekly in 1972. Mad’s wry offspring, The Onion, stopped print publication in 2013, distributing its satire solely online for the last six years.

If I am to bemoan anything in this passing, it is that others who passed through adolescence and read Mad have forgotten or never benefitted from the Mad worldview, that they are unable to admit that they are manipulated by Madison Avenue into chasing after high tech tchotchkes and overpriced vacation cruises; that they are unable or unwilling to consider that their heroes—Clinton, Trump, Bernie, Beto, the list is long—are at least halfway as faulted as their critics claim them to be, and they never understood that Alfred E. Neuman smirked at authority, but he was also smirking at the rest of us, too.