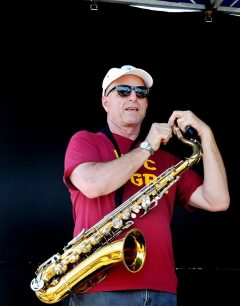

Dave Good

I never set out to become a music teacher. In fact, it all came about quite by accident, and as the result of calamity.

I’d gotten to know the owner of a small family-owned music shop in my new hometown of La Mesa. I’d purchased a second-hand alto saxophone on the cheap, and I didn’t want to blast my neighbors with bad noise, so I rented one of their rehearsal rooms during the off-hours for the purpose of getting my chops back. This was five years ago and up to that point, I hadn’t played any sax at all for years.

I started on alto sax during the 1960s as a fifth grader at Henry Clay Elementary school. My parents scraped together enough coin to rent a Conn saxophone from Ozzie’s Music on El Cajon Blvd. The horn came with three free lessons. I don’t remember what the old doofus with the tenor sax taught me, but I do remember that he was an old doofus with a tenor sax.

By sixth grade, I was in a surf rock band. We called ourselves the Wipeouts. The principal introduced us as the White Belts. We played exactly one song–“Wipeout” by the Surfaris–at one show only. It was the school’s annual talent performance. I sported a crew cut and board shorts and white socks. Our drummer rocked a blue sparkle kit. Our guitar player had one of those gaudy Japanese sunbursts from Radio Shack. The audience went wild.

By high school I was playing in bands with classmates Carl Evans Jr., Hollis Gentry lll, Nathan East, Doug Robinson, Mel Goot, Casper Glenn, Skipper Ragsdale, Gunnar Biggs, Steve Christie, and more. While the rest of the student body was either into folk music or big amplifier rock, we’d quietly discovered jazz, soul, and funk. Eddie Harris and Les McCann and Cannonball Adderley were our heroes.

Fast forward to 1980: I was playing saxes in a funk band with bassist Michael Kennedy. We backed a trio of artists who represented a new kind of music: they called it rap back then. The Sugar Hill Gang had just released “Rapper’s Delight” and it went big, so we jumped on that bandwagon hard and recorded our own rap hit song at Seacoast Studios and Circle Sound Recorders. I shopped the record to every major label in Los Angeles. Personally. I was told that rap was a fad, that the whole thing was one big one-hit wonder. Personally. I went back home and I gave away all of my horns in a royal fit of anger.

I was 27. I figured it was time to earn a living.

Time passed. I didn’t pick up a horn until one day several years later when my mom’s gardener found a perfectly good C-Melody saxophone put out on the curb for trash pickup. It was about a hundred years old, but it played. And I blew that horn for about a year and allowed that music to re-connect me to my past. I had no idea at all how much I regretted walking away from music, which had been my life for the first 27 years pretty much, but so be it.

That’s when I got serious and bought the alto sax and started shedding during the off hours at McCrea Music in the La Mesa Village. It came back fast. First Daniel Jackson and, later, Joe Marillo accepted me as a student. We worked and we gigged together for a few years.

One day at the music store, I learned that the sax instructor at McCrea’s had had a stroke. He was in the hospital and expected to make a full recovery. In the meanwhile, Mr. McCrea asked would I cover lessons and take over the man’s students. I was scared and I didn’t think I could do the job, but I said yes.

A week later, the sax teacher passed away. And that’s when I became a full-time music teacher. And now, I was that old saxophone doofus at the music store, albeit to a new generation of kids who in turn might look back and remember me as such one day. Kind of a humbling thought, yes?

I have since learned some very important things: one, it’s never too late to pick up an instrument and make music. If you are considering getting back to playing, or starting on a new instrument, just do it. You will be glad you did. Music enlarges one’s life in ways unimaginable to those who do not play.

If you are considering learning to play an instrument, you need a one-on-one music teacher. Don’t try to go it alone by watching tutorials on YouTube. There’s a wealth of free information posted there each and every minute, but as the bassist Ron Carter says, you need a teacher to help you find all the notes.

I learned that so many beginners think there’s no hope for them because of a mysterious thing called talent. They think that they don’t have talent. They can’t imagine that John Coltrane or David Sanborn were once beginners and that they, too, sucked at first. It’s true. In our culture and we tend to admire our favorite performers and make them seem bigger than life. That’s a classic error. The bigger the star, the harder they’ve worked to get there and continue to work to stay there. That’s the difference. Work, not talent.

Teaching music seems to be limited to such things as perfecting tone and technique. But beneath the surface, learning to play music has more to do with self-esteem and things like hand-eye coordination, team building, and mental acuity. Studies show that learning to play a musical instrument actually makes you smarter.

And these are the intrinsic qualities that we as music teachers need to identify and challenge and reward. I keep this in mind every time I’m invited to step into a smelly old band room on a high school campus somewhere and lead a woodwind clinic or a sax improvisation workshop or host an introduction to jazz. This is where things happen.

Dave Good writes about pop culture, plays jazz and blues tenor sax in the Dave Good Trio, and teaches saxophone and clarinet lessons at Sam Ash Music in College Grove.