Raider of the Lost Arts

The Police, Part Two

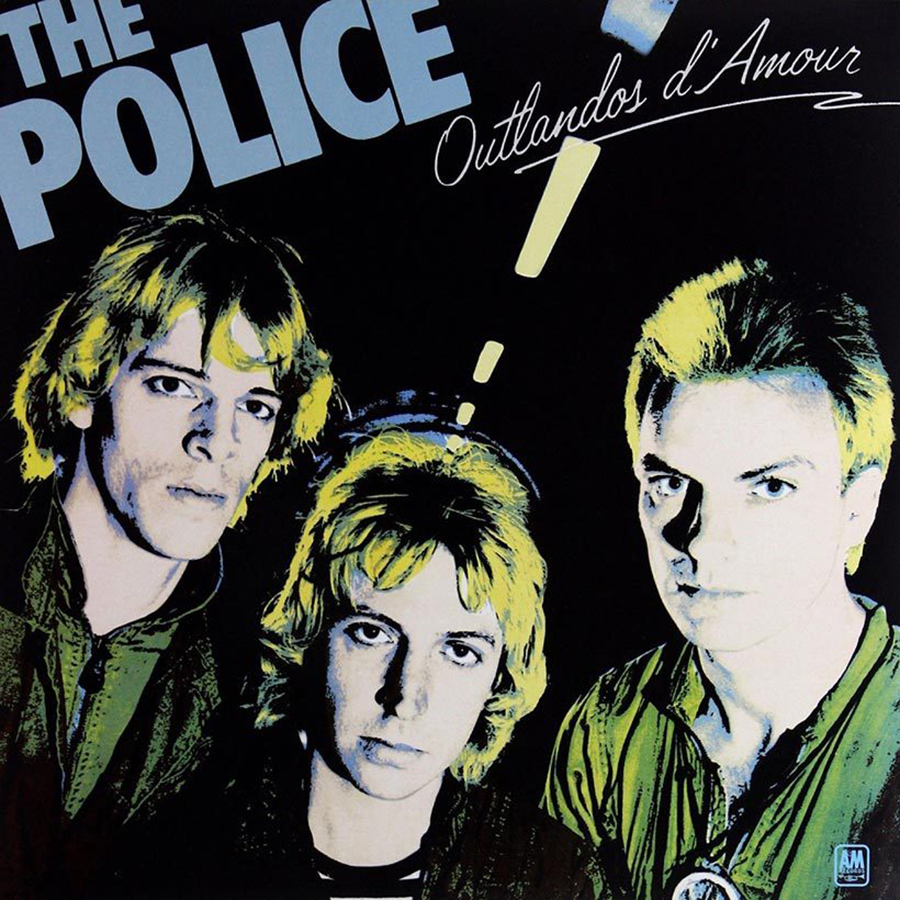

Outlandos d’Amour is deceptive at first blush. The listener is initially assaulted in the debut album’s leadoff track–“Next to You”–by an uptempo barrage of rapid-fire Copeland snare flams and brutal tom work congruent with the prevailing punk ethos (though still technically over the heads of most of the scene’s drummers), and an aggressively sung verse from Sting. The lyrics are the first element to give them away; they’re centered on the author’s lovesick desperation for a distant paramour (or perhaps they’re a pre-diaspora love letter to brass-ring London?), not Thatcher-era oppression, classic-rock-dinosaur rejection (though the eventually hypocritical “Peanuts” addresses the subject a few tracks later), or generation gap maintenance (“Born in the Fifties” is arguably more “Us” than “Them”). This and other Outlandos songs are Beatles-esque in the sense that the Liverpudlian outfit’s early lyrics were an implicit attempt to seduce young listeners into buying their records, and The Police would have fallen flat on their faces had Sting looked anything like his punk peers (if they can even be called that).

All bets are off once the chorus arrives, though. For a start, Summers’ guitar part, mostly line-toeing, muted eighth-note downstrokes in the verses, shifts to broad-swath power chords paired with open strings that shimmer in upper harmonic, space-filling contrast to the maniacally chugging rhythm section (one wonders why Summers ever abandoned the easier album parts and tried to keep right-hand rhythmic pace with the coke-tempoed Copeland at the live shows). And Sting is suddenly accompanied by several clones singing close, rich vocal harmonies, a punk-alienating overdub practice he would not only carry out through the rest of the album, but throughout the rest of the band’s catalog as well. Andy’s solo, also a punk-defying anomaly, is played with a slide on an open-tuned guitar over a temporary key change from E to G Mixolydian, ramping up the tension release with its archaically bluesy, borderline countrified hoedown feel. Finally, the track commits the cardinal sin of fading out, the halfhearted ruse of proletariat rebellion all but entirely abandoned.

“So Lonely” reveals the first semblance of ingeniously modified reggae. In addition to filling melodic space between the verses’ vocals, Summers’ guitar like-mindedly accents the offbeats but doesn’t omit the surrounding eighth notes as is common to the genre. On the verses, Copeland puts the kick and cross-stick-replacing full snare hits back on 1 and 3, and 2 and 4 respectively, and does his tastily nuanced, soon-to-be trademark hi-hat work over the top (Peter Gabriel would eventually tap him for that kit piece alone on at least one solo album track), which punches up the beat into more of a lurching hip-hop groove. The choruses engage the double-time afterburners, with wide-swath whole-note chords by Summers and Sting’s three-part harmonies (in the early days, when Copeland and Summers would join in on those live, especially on this song’s pre-choruses, it was a record-emulating treat). Summers’s guitar solo (“Another solo?!?!” you can almost hear the indignant punters shouting…sorry, but another fade-out as well) is off-the-beaten-path pentatonic, and occurs after an upward modulation from C to D major, a dramatic top 40 device the majority of London’s punk bands also wouldn’t be caught dead attempting, much less have any foreknowledge of (though The Ramones had been hip to it). In addition, Sting shows off his absurdly high, precise, and inimitable vocal range throughout, but especially on the post-solo breakdown vamp, which feels so rhapsodic and joyous as to transmogrify the song’s title into an ironic exaltation.

“Hole in my Life” comes the closest to overt jazz, with a like-minded swinging eighth rhythm and Summers’ college chord stabs on the downbeats offset by a cleverly syncopated toms-on-2 and snare-on-4 groove by Copeland. Sting has been quoted as saying something to the effect that the bass note determines the tonality of the chord played over it; he proves it somewhat true in his creation of tasty inversions and “slash” variations–chords with a non-root note in the bass–in many songs, including the chorus of “Hole in my Life,” which, coupled with doubled and harmonized vocals, Sting’s legato octave bassline, Copeland’s symphonic crashes, and Summers’ splendiferous strums, gives this and other Outlandos songs a cinematically orchestrated, greater-than-the-sum-of-its-three-parts grandeur. And the lyric for this track (notwithstanding “So Lonely”) actually expresses the author’s dark state of mind unrelated to heartbreak, the kind of inconsolable isolation that would go on to conspicuously inform songs like “Message in a Bottle” and “King of Pain.”

Below is a video of a stellar performance of “Hole in my Life” in the middle of the band’s live appearance on the German TV show Beat Club in 1978; especially noteworthy is Sting’s “Fixing a Hole” McCartney quote at 16:19, his show of solidarity in “So Lonely” at 1:42 (“Welcome to this three-man show!”), and the genuinely corroborative, early-days smile he gets from Stewart at the top of “Born in the Fifties” (8:53):

Though the Copeland-penned first single–“Fallout”–got left by the wayside, punk holdover “Truth Hits Everybody” managed to pass muster. Featuring one of Sting’s more vague but nevertheless interesting lyrics (heartbreak-induced suicide? Reckoning with an all but ended relationship? Facing the music some other way? It’s tough to tell), the song is zhushed up by one hell of a chorus hook and some off-the-beaten-path chord choices and voicings from Summers. Sting’s poetic wordplay and imagery are about as far from punk’s mandated furor as a lyric can get:

Sleep lay behind me like a broken ocean

Strange waking dreams before my eyes unfold

You lay there sleeping like an open doorway

I stepped outside myself and felt so cold

Take a look at my new toy

It’ll blow your head in two, oh boy

Truth hits everybody

Truth hits everyone

“Be My Girl / Sally” and “Masoko Tanga” initiate trends for non-Sting contributions and the kind of ad hoc “killer filler” tracks they had to cobble together because they so often found themselves short on material in the studio. Summers humorously interjects in the middle of what is essentially a jam on one line of Sting lyrics and one chord progression on “Be My Girl / Sally” with a droll, Yorkshire-accented narration about a romance with a mail-order blow-up doll. Meanwhile, a piano–probably played by a bored and / or impatient Sting–restlessly and atonally plinks away in the background. “Masoko Tanga” is essentially a reggae-tinged mid-tempo jam with incoherent toasting vocals from Sting and staid playing from the band that still manages to sound vital (Sting’s overdubbed bass fills–and to a lesser, more shock-valued extent, a random yelp from Summers at 1:17–help to break up any perceived monotony).

Regatta de Blanc, the exact opposite of a sophomore slump, finds the band at its early apogee, completely unified in their professional and musical drive, not yet entirely at each other’s throats, coming off the high of their first US tours with an abundance of fresh ideas and synergistic purpose. A&M asked for a new album to capitalize on the recently generated buzz, and The Police were more than willing to oblige, but they spurned the label’s recommendations to use a “better” studio and co-producer / engineer in favor of sticking with the working formula that was already in place with Nigel Gray at Surrey Sound. Oddly enough–or not, if one considers the fact that Gray had been busy honing his skills with other clients in the interim–this second album, recorded and released only a year later, sounds noticeably better than Outlandos d’Amour, which had more of a muted, low-fi punk feel paired with inferior reverb (though to the band’s well-earned credit they still managed to shine right through).

Sting’s immediate goal was to outdo “Roxanne,” and he did just that with the leadoff track, “Message in a Bottle.” Copeland’s introductory flams smack of “Next to You” album-christening frenzy, but that’s where the familiarity ends; Summers co-instigates with an unusual, Sting-composed, offbeat-accenting, harmonized 9th chord riff over Stewart’s initial hits, and a lurching groove kicks in under the first verse, which finds Sting on a novelty-laden fretless electric bass (Jaco Pastorius was already well on his way to revolutionizing technique and tone with his de-fretted Fender Jazz), which he would utilize on much of this and successive albums, and for years after in the live milieus. The chorus gives way to the first sign of reggae, with Copeland’s four-on-the-floor hybridization (arguably his oft-aped invention) and Sting’s syncopated bassline underscoring wide-swath jazz chording by Summers.

The lyric is neither love- nor rebellion-related, but a lonely man’s cry for help (“Rescue me before I fall into despair”). But Sting puts his soon-to-be trademark twist in at the end, disarming the off-putting potential for self-absorption with massively relatable, personal-to-universal flare: “Walked out this morning / Don’t believe what I saw / A hundred billion bottles washed up on the shore / Seems I’m not alone at being alone / Hundred billion castaways looking for a home.” (Easter egg: if you crank up the volume during the album version’s long fade-out, you can hear Sting sing “Sending out an S. O. BLUE” at the very end of the long string of “Sending out an S. O. S.”)

The title track is an outgrowth of the first-tour experimentations the band had conducted with the bridge and final verse sections of “Can’t Stand Losing You,” with a wordless–or at least simplistic (“Yo,” a soon-to-be-trademark vocal affectation for Sting, along with the preceding “CHA!”)–melody which, coupled with the crescendoing music, gives the piece an infectiously anthemic feel. Copeland makes the groove lurch compellingly in the first section with two kicks on the 2nd, snare hits on the 4th beat only, and lots of tasty accents on the ride cymbal bell. The drop-in to the B minor section at the end of the vocal buildup is absolutely epic in its cathartic rock release.

“It’s Alright for You” feels like a potboiler punk leftover (with a self-referencing slide solo from Summers à la “Next to You,” but also a complementary single-note line over the outro) with unfocused lyrics compared to “Bring on the Night,” the second classic track of the album. Sting’s VI VII i verse bassline, chunked out with the plectrum he would later detrimentally abandon, underscores the ingenious guitar part: an elegantly fingerpicked arpeggio pattern pairing roving sixths with the open first string (E4). The choruses probably come as close to flat-out reggae they would ever dare, with the exception of Sting’s unrelenting, loping bassline and Copeland’s occasional accenting cymbal crashes on 2 and 4.

Sting’s poetically philosophical lyric speaks to his preferred time of day, when everything good–Police shows, nightlife, romance, sex–typically happens in a touring band’s life (George Benson’s “Give Me the Night” would wax similarly a year later). Already a standout track backed by Copeland’s rudimentary one-drop kick drum placement and offbeat-accented hi-hat part, Sting’s octave-doubled vocals add the kind of subtle production touch for which the band haven’t been sufficiently recognized. The minimalistic, borderline erratic guitar soloing from Summers, similar to that on “Message in a Bottle” and “No Time This Time,” feels like a cheeky, passive-aggressive reaction to the no-solo mandate foisted on him by punk and surreptitiously championed by Sting as a way for the frontman to hog the spotlight.

The Bo Diddley-ish “Deathwish” takes another stab at the self-destruction obsession Sting had already and would later explore in greater depth on several Ghost in the Machine tracks. The lyrics reflect a stepping-outside-oneself shock at his self-accused taking-chances-not-risks behavior (“Deathwish in the fading light / Headlight burning through the night / Never thought I’d see the day / Playing with my life this way”) and the signature wry cheek à la Mercutio’s “Ask for me tomorrow and you shall find me a grave man” that balanced out his gravitas: “The day I take a bend too fast / Judgment that could be my last / I’ll be wiped right off the slate / Don’t wait up ‘cause I’ll be late / I’ll be late” (see what he [and Mercutio] did there with “late” [and “grave”] as a homonym?). Musically, Sting self-plagiarizes and upwardly transposes the intro bass riff from “Can’t Stand Losing You” for the between-verse rave-ups, pushing it up a whole step over Copeland’s manic double-time skinning and under Summers’ space-leaving natural harmonics.

There are some genres in which it is all too easy for a practitioner to get lost and pigeonholed; this is especially true of Jamaican-sourced ska and reggae. The emphasis on the offbeat is an instantly recognizable sound that can become a quagmire from which any appropriator might find it difficult to extricate themselves and their work. One can’t think of reggae, for example, without musing on Bob Marley (who approved of The Police’s appropriation); it is his blessing and curse that the two have become synonymous. But the main difference that separates Marley from other reggae artists who have become lost in the trope maze are the strong underlying works. One could deactivate the reggae feel of any of his classics, put it through a different genre filter, and it would still be just as impactful (Big Mountain’s cover of Peter Frampton’s “Baby I Love Your Way” and The English Beat’s reading of Smokey Robinson’s “Tears of a Clown” illustrate this in reverse). Nevertheless, some songs can benefit from the feel on a symbiotic, deoxyribonucleic level without getting lost in it.

It’s a difficult balance to attain and maintain, but the classic “Walking on the Moon” does so with clever, stereotype-mutating aplomb. The Police never went full reggae; in fact, they were always somewhere between reggae and ska in their use of the characteristic devices, with rock ‘n’ roll and jazz never too far away, and usually with only one or two members’ parts immersed in the idiom. Summers’ two guitar figures tip their hats but don’t bend the knee, with one track being an Echoplex-stretched, shimmering D minor 11th chord that hits on the “and” of 1 in the first measure of Sting’s jazz-inflected two-measure bass theme, holding until the next strike (that pace naturally doubles on the choruses), and the other does the expected offbeats in an understated, inverted-upper-harmony-triad way. Copeland’s part goes from offbeat-accenting kick drum with cross-sticking on 2 and 4 in the verse to four-on-the-floor kick in the choruses, with occasional, rapid cross-stick / hi-hat flourishes augmented by dub-congruent delay that had become a Copeland calling card from “Can’t Stand Losing You” on.

Sting’s high-sung lyric, with its “Giant Steps” allusion to the John Coltrane album of the same name, is another indirect reference to being in love (or perhaps a wary yet heady recognition of his newfound “Shoot the moon” success?), comparing it to the space-age sensation of freedom from gravity. His bass line, a melodic motif in and of itself, underpins everything, even and especially with the space it leaves. And you can feel him call-and-response goading the listener–and can already imagine the crowds echoing–his chants of “Yo’” and “Keep it up” at the end.

“On Any Other Day” is the first of three cuts Copeland was allowed to put on the album due to the usual dearth of Sting material, and hardly the best of the lot; lines like the spoken opening disclaimer, “The other ones are complete bullshit [does he mean Sting and Andy??] / You want something corny? You got it” and the bigoted “My fine young son has turned out gay” have not aged well, if indeed they were ever young. But the song maintains the sonic status quo as far as their trademark killer filler goes, with its blending of punk, rock, and reggae devices, and the band manages to spruce it up with Sting’s harmonizing backing vocal throughout, his acrobatically melodic bassline, Copeland’s usual genre-blending drum frippery and lurching groove, and Summers’ overlapping overdubs.

“The Bed’s Too Big Without You” ramps the proceedings back up with another undeniable chestnut. Sting’s bassline, a motivic melody in itself, leaves the rarified space of reggae, but coupled with Copeland’s hybridized drum part–a unique combination of like-minded one-drop kick drum paired with an unusual Lebanese-inspired 16th-note snare pattern accenting the offbeat of each measure–it creates the kind of brilliantly constructed and compelling groove heretofore unheard of in pop music (Easter egg: amazingly enough, Copeland’s drum parts were usually cooked-up-on-the-spot first takes, and sometimes errors were made, and were kept in; check out the kick drum flub at 2:48). Summers’ guitar chords, mostly minor sevenths, chunk away above and beyond reggae’s confines like an additional percussion instrument, accenting in tandem with Copeland, then dropping out entirely for the shaker “solo” interlude, which is minimalistic genius.

The lyrics pine for an absent lover, but again in a refreshingly indirect way. Additionally, and in a distinctive twist, they actually cop to the singer’s full culpability for his own solitary condition (“All I made was one mistake / Now the bed’s too big without you”), something about which you can’t find many other singers of the day–or any day–being honest. The melancholy feel and plaintive reverb go so far as to almost exculpate the singer from his adultery and win the listener over to his side, as though the punishment of agonizing solitude was disproportionate to the crime. It’s an impressive feat in itself, and one of many surprises Sting would ultimately deliver and become widely known for.

This song became one hell of an improvisational playground–not to mention a mat for dirty fighting–at the live shows; in an effort to trip up his drummer, who typically instigated the song with his part, Sting would often shout the introductory four-count for his and Summers’ triplet-accented entrance on the offbeat instead of the implied downbeat, a spike strip he would throw out for the high-speed-chasing Copeland on the freeway of other songs as well. After the squabbling rhythm section got that out of their system, the second chorus would hurdle over the cliff of a brief pause, and the exploratory fun would begin, with everyone hanging back more often than not, variations on the bass theme and vocal improv from Sting, peak-and-valley Mitch-Mitchell-isms from Copeland, and Summers switching on the Echoplex for eerie, echoing-to-the-beat upper harmony swells and runs.

“Contact” goes a little further than “On any Other Day” to help Copeland hold his ground as a contributing songwriter. His drum part during the half-time verses groove heavily thanks to the offbeat-accented working of every juicy part of his ride cymbal, and the relentless double-time interludes glisten with melodically complex, complementary Summers overdubs (with no guitar whatsoever during the verses!) and Sting’s single-note fretless bass drones doubled by a rhythmically filter-sweeping synth part. It feels like The Police’s quirky, minimalistic heralding of keyboard-driven new wave.

The lyric lacks substantial definition or heft, but manages to dovetail with Sting’s go-to romantic themes, including the self-doubt that often comes during the early dating phase of a relationship: “I’ve got a lump in my throat / About the note you wrote / I’d come on over / But I haven’t got a raincoat / Have we got contact / You and me? / Have we got touchdown / Can’t we be?”

The same can be said–except with more clarity and focus of intent–for the subsequent “Does Everyone Stare,” arguably the best Copeland song to make it onto a Police record. His piano part, a brilliant bit of multi-voiced, upper harmonic genius in itself, was originally written to fulfill a homework obligation for a composition class during a stint at a stateside college. It starts with Copeland sotto-voce mumbling the first verse over piano and bass, then the unplanned but perfectly timed production touch of a scratchy old recording of an operatic tenor singing a line from an aria swelling up emotionally and then out, apparently a crossed-wires-as-antenna fluke from Copeland’s home-recorded demo. Then the effectively minimal half-time drums fade in under the first line of lyrics. Sting works his usual lead and harmonizing vocal magic on his bandmate’s song, a service he would be progressively less inclined to provide to either Copeland or the here noticeably AWOL Summers as they moved forward. (Easter egg: the purposefully [?] janked bass note and chord at 1:02.)

Copeland endears himself to the listener with relatable lines like “I change my clothes ten times before I take you on a date / I get the heebie-jeebies and my panic makes me late / I break into a cold sweat reaching for the phone / I let it ring twice before I chicken out and decide you’re not at home,” “I’m gonna write you a sonnet / But I don’t know where to start / I’m so used to laughing / At the things in my heart,” and the quirky “I never noticed the size of my feet / Till I kicked you in the shins.”

Copeland’s fire continues to blaze on “No Time This Time,” even if only to feature his maniacally fast yet precise punk-on-crack drumming. The intro and end fills alone are worth the price of admission, but the way they complement Sting’s high-shouted lyric about the progressively increasing busyness and resulting stress of their hectic lives, told with personal-to-universal flare via succinct descriptions of quotidian scenarios, is onomatopoetic perfection: “No time for a quick kiss at the railway station / Just time for a suitcase, sandwich, and a morning paper / Only time for time tables and transportation / No time to think, no time to dare.”