Raider of the Lost Arts

The Police, Part 4

The Police was a band that exploded onstage and imploded in the studio.

––Stewart Copeland (via YouTube interview)

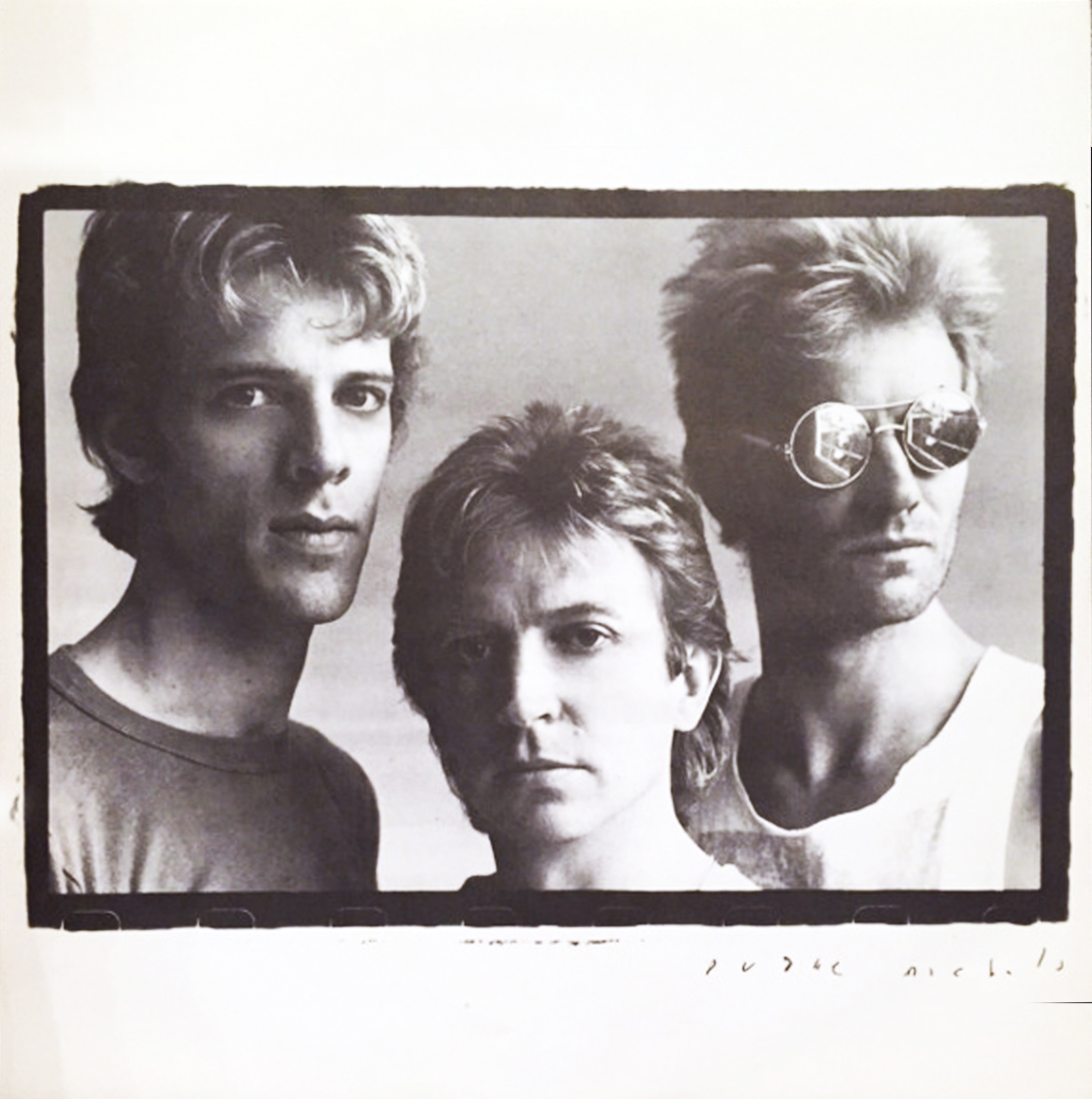

The Police

AIR Studios Montserrat must have provided a good enough experience––and Hugh Padgham a sufficient collaborative result––to inspire the band’s return with him to record what would end up being their fifth and final studio album in December of 1982. However, one would think that with the intense friction threatening the structural integrity of the entire enterprise from within, and with the trio incapable of ameliorating the wounds or even maintaining the brittle détente, the band would blame and subsequently choose to change their surroundings instead of returning to the acrimonious scene of previous ego crimes. But since The Police were such a volatile creative force, it follows–and experience shows–that they knew to leave well enough alone and stay loyal to a proven studio paradigm as a stable, isolated port in the chaotic music industry storm, and to rely on a familiar anchor in the tumultuous sea of mutual hostility (the band–and A&M–were probably too lazy to investigate other options anyway). Besides, they had enjoyed enough success with Ghost in the Machine––though not enough to precipitate their dissolution—to sustain group cohesion on the corroborative Montserrat isle long enough to reach the pop music summit.

Andy Summers paints a poignant portrait of the band’s emotional state in his excellent 2006 memoir, One Train Later:

[Chapter 25] It seems as though Sting is at the North Pole, I am at the South Pole, and Stewart is in the tropics. We are the emotional opposites of when we recorded Outlandos. Arriving to record another album suddenly wipes the glass clear and we stare at one another as if in assessment. In the shocking calm of the studio, without the blanket of touring, the need to make it to the next gig. The mud drops to the bottom of the glass and we eye each other like strangers.

We’ve changed. Sting, after a year of celebrity highlights––his high-profile court case against Virgin [to rectify the aforementioned publishing share disparity], his movie appearance in Brimstone and Treacle [he would film his scenes for David Lynch’s Dune the following year] and endless appearances in the press––is now someone else. It changes you, how could it not? The inevitable corrosion is eating its way through the tenuous threads that have held us together so far. But whatever monster lies beneath the surface goes unremarked.

We strap on the band persona; we still have a goal, still have fire, still have desire, still want a number one record in the United States. We begin tentatively at first, mostly listening to the new batch of songs that Sting has conjured up… As usual, there is some good material but it needs the Police signature, needs to be toughened, and we get to work.

[Chapter 19] I have wondered ever since we completed Regatta de Blanc how long Sting would play this game, because it doesn’t seem natural to him. He is not a team player, doesn’t really want to share credit, and makes comments in the press to that effect, as if foreshadowing the ultimate event. I understand, and it feels like a small interior abrasion that is quiescent at the moment but may one day become a wound that will hold the residual pain of being deserted by someone you love. In the classic distortion that always happens with bands, we might already be reaching the point where we think we don’t need one another, can go it alone, pull apart like the Beatles. It seems that each one of us really would like to run the whole show or be out on his own. Stewart, brash and outspoken, bulldozes his way through things, Copeland-style, but achieves his goals. If left to our own devices, Sting and I would probably get too subtle, too esoteric; Stewart counters all that and gives things a fuck-you rock-and-roll edge.

[Chapter 25] In the studio the tension is so high that you can hear it twanging like an out-of-tune piano. As a group we seem to swing between high emotional intensity and sophomoric fraternity with frightening ease, almost like a group version of bipolar disorder. The best result is that when “it” happens, we can play with an empathy that is hard to imagine achieving with other people. But making albums is a brutal affair: you are forced to stand down, moodily let go of an idea, play someone else’s idea, watch all your cherished licks go out of the window––often accompanied by boos and jeers. It’s painful because none of us likes being told what to do or being controlled in any way. In truth, we are like children locked in a house with big shiny machines and a handful of explosives. But from the pain comes the growth––and that, we tell ourselves or one another after having just trashed some musical effort, is what it is all about.

Synchronicity, The Police’s final album.

Hugh Padgham unwittingly reinforced The Police’s in-progress disintegration by setting them up in three different rooms to record their parts––with Sting appropriately situated in the control room––in order to attain the otherwise strived-for studio ideal of “perfect separation.” The irony, though, is that this sequestration may have also been Padgham’s only recourse in terms of mitigating the malaise, at least while the tape was rolling. At one point, Summers recalls the tension becoming so unbearable that it stopped the band in its tracks, rendering them totally unable to continue, almost putting an end to everything right then and there on that island. Summers was subsequently sent off to seek the wisdom and guidance of renowned studio owner George Martin, who told them via Andy to simply buck up and get on with it (not dissimilar to the encouragement he gave to the Beatles for Abbey Road), which they somehow managed to do, as if Martin had waved his hand and dispelled the bad juju like some kind of music business wizard (or as Summers himself stated, like Obi-Wan Kenobi). They reconvened with a revived interpersonal courtesy to finish the album, which by then they must have all at least subliminally realized would–and needed to–be their last.

Again, Sting had done his homework, with some songs demoed and many new books read, including Carl Jung’s autobiography and the volume bearing the same name, which expounds on the concept of synchronicity––aka coincidence––that would inspire the album’s appellation and two of its songs’ lyrical concentration (Arthur Koestler––and specifically his 1972 book The Roots of Coincidence––again figures prominently as well). Jungian psychology became a shared interest with Summers, who had actually undergone that therapy and now related his experiences––and also recommended another song-inspiring book: Paul Bowles’s The Sheltering Sky, the story-within-the-story of which inspired “Tea in the Sahara”–to the band’s premier songwriter.

“Synchronicity I,” as it did for the supporting tour’s shows, kicks off the proceedings with fast-paced brio. An uptempo percussion loop (courtesy of an Oberheim DSX sequencer) in triple meter and C Dorian modality, provided by Sting and not Copeland as one might assume, is joined by the latter’s ride cymbal bell accenting various offbeats (mostly the third of four sixteenth notes) in a shimmering flurry before dropping into a rhythm that would signify the last echo of punk in The Police’s music, now blending with the album––and classic-rock-radio-dominating dentist-office fusion Sting would subsequently pursue as a solo artist. Summers plucks and strums away on a 12-string electric guitar for the first and only time while Sting chunks out unwavering sixteenth notes on the tonic with his bass as he sings about as poetically as anyone ever could (though he seems to be the only one to have made the attempt thus far!) about the butterfly effect and the collective unconscious:

With one breath

With one flow

You will know

Synchronicity

A star-fall

A phone call

It joins all

Synchronicity

A connecting principle

Linked to the invisible

Almost imperceptible

Something inexpressible

Science insusceptible

Logic so inflexible

Causally connectible

Nothing is invincible

If we share this nightmare

We can dream

Spiritus mundi

If you act as you think

The missing link

Synchronicity

We know you

They know me

Extrasensory

Synchronicity

It’s so deep, it’s so wide

Your inside

Synchronicity

Effect without a cause

Sub-atomic laws

Scientific pause

Synchronicity

Another sequenced percussion loop presides over the following “Walking in Your Footsteps,” where Sting directly, ingeniously addresses our dinosaur predecessors in recognition of the mounting possibility of our own mass extinction. The main difference with mankind, of course, is that we will most likely bring it upon ourselves, whether ironically through the excessive burning of fossil fuels––the physical remains of the very subject to which he sings––or through the mutually assured destruction of nuclear conflict. In the early eighties, the escalating cold war still held sway through that paranoiac fear, and it manifested in many of the contemporary bands’ lyrics, including these:

Fifty million years ago

You walked upon the planet so

Lord of all that you could see

Just a little bit like me

Walking in your footsteps

Hey Mr. Dinosaur

You really couldn’t ask for more

You were God’s favorite creature

But you didn’t have a future

Walking in your footsteps

Hey mighty brontosaurus

Don’t you have a lesson for us

You thought your rule would always last

There were no lessons in your past

You were built three stories high

They say you would not hurt a fly

If we explode the atom bomb

Would they say that we were dumb?

We’re walking in your footsteps

They say the meek shall inherit the earth

Sting sings the first two verses down in the middle C area and jumps up an octave from the long last verse on, an exciting dynamic shift over Copeland’s stick-click-augmented but otherwise static backing track that gives the cut a likeminded primordial, tribal world music feel (reinforced by Sting’s pan pipes and Summers’s overdriven volume swells of vibe-abetting chords and notes).

The following verse was one of two that ended up being cut from the final version to conserve vinyl space but found its way into the live rendition:

They say it’s our distinction

To laugh at our extinction

But you really have to think hard

When you’re walking in your graveyard

Fifty million years ago

They walked upon the planet so

They live in a museum

It’s the only place you’ll see ‘em

It’s difficult to sing of the Judeo-Christian God without coming off as either overly pious or atheistically dismissive, but Sting manages an agnostic balance of sentiments on Synchronicity’s third track, the OMG-preempting, simultaneously beseeching and admonishing “O My God,” where he confronts a more familiar deity’s hypocrisies while at once wishing He were closer, more evident:

Everyone I know is lonely

With God so far away

And my heart belongs to no one

So now sometimes I pray

Take the space between us

And fill it up some way

Take this space between us

And fill it up, fill it up

Oh my God you take the biscuit

Treating me this way

Expecting me to treat you well

No matter what you say

I cannot turn the other cheek

It’s black and bruised and torn

I’ve been waiting

Since the day that I was born

Fat man in his garden

Thin man at his gate

My God you must be sleeping

Wake up–it’s much too late

Sting’s voice, a quirky and distinctive instrument in itself, helped set The Police apart even more. Possessed of a high range and reedy timbre, which was actually quite similar to the alto saxophone he fetishized, his voice cut through the minimalistic yet busy band mix and couldn’t help but draw attention to the unconventional words he sang, not to mention the frontman himself. His Saxon roots had him gravelly and hoarse down in the lower reaches, but clear and piercing up high, where he spent much of his time. In this light, key modulations––and genre modifications––for many of the songs on the 2007- 2008 reunion tour, though perhaps disappointing to the purists, were a prudent necessity, and actually took strategic advantage of his aged and worn voice’s augmented low end.

It’s virtually impossible to continue singing as he did in The Police, and the same holds true for any other male singer regularly residing in those rarified rafters, but Sting sounded in peak shape on the reunion tour, and even managed to show off some new tricks in the process (somewhere along the line he had learned breath support and sustain; listen to that tour’s half-step-lowered version of “Walking on the Moon,” whether on Certifiable or YouTube, where he hits the line, “Walking back from your house” out of the park on a nightly basis with an average hold of at least 10 seconds at G#4 on the indicated word), though he never really did come around to vibrato.

On “O My God,” you can hear the gruffness of seven years of relentless recording and touring having taken their toll on his vocal cords, with Sting sounding ragged and short of breath in a way that actually fits the song (the same could be said, though to a lesser extent, regarding “album closer” “Murder by Numbers”). It was a rare show on any of the tours when he wasn’t suffering from some degree of laryngitis, so it’s an awe-inspiring surprise that he could even hit the high notes this late in the game, let alone in 2007-2008.

Sting’s chorused fretless bass themes––which are on the verge of being too loud in the mix, as Copeland’s kick drum tended to be––float atop Copeland’s seamlessly phase-shifting drums as he glides from section to section and disparate part to part in restrained service of the song, that is until the F# minor wind-down at the end, when everything goes off the rails. Summers floods the upper frequency soundscape with volume-faded, harrowing washes of sound (the Roland guitar synthesizer and some other unidentified instrument, probably slide or keyboard) while Copeland lead-foots the percussion throttle and Sting wails away like John Coltrane’s understudy until the bass fades and it’s just the sax and drums slugging it out for a moment. Finally, the saxophone finds itself alone, just like its wielder would a year or two later, and the restrained plaintiveness of the heavily reverbed melody that closes “O My God” is such a sudden, heartrending shock to the system that one can only sit in reflective, stunned silence until the next track begins.

If one of the functions––and perhaps the very definition––of art is to provoke a strong positive or negative reaction or emotion, and perhaps evince some degree of attraction or repulsion (or both), then Andy Summers succeeded in spades with his allotted Synchronicity contribution: the fan-polarizing “Mother.” The only familiar aspect of the song is its traditional blues structure embodied by the verses’ I IV I V I chord change and repeated lyrics, which has been ground down to a marbled pulp through the sausage maker of a 7/8 meter and an arpeggiated pattern employing a descending line which begins with a flatted ninth. These clever tweaks create the right tritone tension to provide sufficiently deranged, exotic context for Sting’s eastern-inflected oboe melodies and Copeland’s pagan, four-on-the-floor percussion and violent china crash accents. And that’s just for starters; Summers, who had garnered Sting’s amused ear but not his cooperation in the vocal booth, goes utterly Oedipal in the lyric and sings with the kind of manic abandon reserved for long-term amphetamine addicts and sanitarium residents.

Copeland’s contribution is once again lumped in following Andy’s in the form of “Miss Gradenko,” lyrically an enigmatic espionage thriller with a fantastic fingerpicked arpeggio guitar part reminiscent of “Bring on the Night” (one wonders which of the three wrote this wonderful pattern, since “Bring on the Night” was Sting’s, and this is Stewart’s, who chose guitar over keyboard this time and whose skills on this instrument were not up to the task. Perhaps this is Andy’s reading of what Stewart’s original piano part might’ve been?), and some killer grooving from the rhythm section (Copeland’s off-kilter fills back into the verses are perfectly timed and played, and Sting’s galloping bass on the latter verse sections––and his acrobatic line on the choruses––are harmonically and rhythmically compelling).

The next two tracks, the most commercially successful of the album, offer up a master class in contrasting approaches to pop songwriting.

At the end of side one, though deserving of pole position, “Synchronicity II” takes us on an incredible journey, showing us the underlying concept whereas “Synchronicity I” just tells us of it (again, no one else before or since has made the attempt to even tell us). It’s an ingenious lyric that mixes the archetypes of a terrestrial day and the quotidian dynamics of the stereotypical modern family with the almost believable myth of Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster (which, as the best horror and sci-fi directors know to do, is only indirectly referenced in the lyric), which had been steadily growing in notoriety, thanks to contemporary TV shows like That’s Incredible and Ripley’s Believe It or Not. Sting also manages to subtly weave in anti-industrial and environmentalist sentiments, meta-references “Roxanne” with “Cheap tarts in a red light street,” linguistically tips his hat with the very Scottish pronunciation of “alone” in the line, “Daddy grips the wheel and stares alone into the distance,” and perfectly encapsulates each gender’s timeless struggles with our grating modern realities. He ties the male protagonist’s steadily mounting yet stoic desperation in with the monster’s movements as the young Gordon looks on and narrates:

Another suburban family morning

Grandmother screaming at the wall

We have to shout above the din of our Rice Krispies

We can’t hear anything at all

Mother chants her litany of boredom and frustration

But we all know her suicides are fake

Daddy only stares into the distance

There’s only so much more that he can take

Many miles away, something crawls from the slime

At the bottom of a dark Scottish lake

Another industrial ugly morning

The factory belches filth into the sky

He walks unhindered through the picket lines today

He doesn’t think to wonder why

The secretaries pout and preen like

Cheap tarts in a red light street

But all he ever thinks to do is watch

And every single meeting with his so-called superior

Is a humiliating kick in the crotch

Many miles away, something crawls to the surface

Of a dark Scottish loch

Another working day has ended

Only the rush hour hell to face

Packed like lemmings into shiny metal boxes

Contestants in a suicidal race

Daddy grips the wheel and stares alone into the distance

He knows that something somewhere has to break

He sees the family home now, looming in his headlights

The pain upstairs that makes his eyeballs ache

Many miles away, there’s a shadow on the door

Of a cottage on the shore of a dark Scottish lake

The backing tracks, individually brilliant and synergistically paired with the lyric as a whole, are cinematic despite their minimalism. At the track’s onset is a dramatic Lydian synth melody, and Andy’s guitar feedback dropping in from supersonic heights, the result of a studio trick involving the manual manipulation of the tape speed while recording. Then Summers counts everyone in with three A3s that numerically connect it with “Synchronicity I”’s triple meter. The F#m7-based intro features another anthemic vocal-chant from Sting over his aggressively bowed upright-bass emphasis on the root. The single-note guitar and bass lines of the early verses intertwine in the A Mixolydian modality, reinforcing the frenetic but innocuous outward tension of each corresponding scenario presented in the lyric. Summers and Copeland open up on the verses’ second section, emphasizing the subjects’ inner tension with held A, D/A, B7/A, and back to D/A strums and restless ride work respectively. Sting’s bass again pedals on the tension-extending part–this time on D–while Summers does two of each note in a Dm7 and G7/D arpeggio, adding a complementary countermelody to increase the harmonic coverage. That section ends with a fitting crash accent on E following the words “take,” “crotch,” and “ache.” Finally, to emphasize the switch of focus to the ominous creature, the continuo modulates to A minor, tracing down to the alternating V and VI chords of the Phrygian modality, which grants the familiar half-step tension native to Spanish and flamenco music, and sees this masterpiece out as it fades.

Perhaps it’s the ear fatigue talking (in 2019, BMI acknowledged this side 2 leadoff track as being its most played in radio history, thusly accounting for a substantial percentage of Sting’s annual publishing revenue), but there’s really nothing that distinctive about The Police’s best-known song, “Every Breath You Take.” The assertion that there is a subtle but unmistakable stalker twist to the lyric comes off like a retrofitted afterthought, and the only element that makes it sound anything like a Police song is Andy’s brilliant but palm-muted signature arpeggio guitar melody that he apparently did in one take after receiving Sting’s sadistic encouragement to go in and make it his own. Copeland is deprived of his beloved hi-hat and ride cymbal flourishes and is forced to make do with passive-aggressively hitting his snare drum about as hard as he ever possibly could or did, the probable result of him and Sting arguing for hours over where the kick drum should reside. A piano and a cheesy synth pad add schmaltzy gloss across the top frequencies, and the chord changes––and even some of the vocal hooks (and lyrical themes?) ––are merely variations on one of the even by then criminally overused “Fifties progressions” (I vi IV V), which adds to the overall dumbed-down, appeal-to-the-lowest-common-denominator pop oversell. In other words, if there were ever to be an obvious sell-out track singled out in The Police’s oeuvre, with selling out defined as an artist or band significantly modifying and / or simplifying its sound in quest of commercial success, “Every Breath You Take” would be the one. Considering how adventurous most of the other Synchronicity tracks are, this song sticks out like an anomalous sore thumb in its milquetoast conformity. (In a current-news twist, Sean “P Diddy” Combs will now be hard-pressed to pay the astronomical monthly fee for his 1997 sampling of this song in “I’ll Be Missing You,” considering his latest legal troubles and all but impending incarceration.)

Summers had suggested they put all the “upbeat” songs on side 1 and the mellower content on side 2, which Sting ordained, and the rest of the album–all but one completely Sumner-penned––adheres to that mandate. Even “King of Pain”’s choruses are relatively sedate compared to anything on side 1, with Sting singing the lion’s share of the song in his lower register (he briefly hits B4 in the end vamp, as high as he would let himself get here…past Sting might have taken umbrage, present Sting is laying the track for his singular, soporific jazz-pop future). Again, his perfect vocal hooks give him carte blanche to sing any words he damn well pleases over the music without affecting the hit potential (one could rightly dub this the “Sting principle”), but the lyric, which is indirectly self-referential (he even speaks of his soul in the third person), portrays a visceral parade of heartrending imagery by which the singer and listener are both deeply affected (this is probably the only way Sting could allow himself to be vulnerable: if he knew he was making millions of listeners feel exposed too):

There’s a little black spot on the sun today

It’s the same old thing as yesterday

There’s a black hat caught in a high tree top

There’s a flag pole rag and the wind won’t stop

I have stood here before inside the pouring rain

With the world turning circles running ‘round my brain

I guess I’m always hoping that you’ll end this reign

But it’s my destiny to be the king of pain

There’s a fossil that’s trapped in a high cliff wall

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a dead salmon frozen in a waterfall

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a blue whale beached by a springtide’s ebb

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a butterfly trapped in a spider’s web

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a king on a throne with his eyes torn out

There’s a blind man looking for a shadow of doubt

There’s a rich man sleeping in a golden bed

There’s a skeleton choking on a crust of bread

There’s a red fox torn by a huntsman’s pack

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a black-winged gull with a broken back

(That’s my soul up there)

There’s a little black spot on the sun today

It’s the same old thing as yesterday

I’ll always be king of pain

Copeland comes back to life here, with a crafty snare hit on the post-intro “and” of four that inaugurates a nice second verse groove comprised of an offbeat kick pattern a la “Man in a Suitcase” and some signature hi-hat work. He also plays a texture-augmenting marimba line over the stripped down intro (an effective use of dynamics that didn’t happen until the mixing phase; apparently the initial version featured the full band playing all the way through), adding more new instruments to his CV. Summers, as he does through most of side 2, contributes minimalistic but wildly effective guitar textures here, with haunting high note bends over the intro that help the evocative lyrical imagery hit home even harder, then he plays his version of the vocal melody a well-placed octave above to cover a wider Hertz range for the drum-accompanied verses, and finally brings out the big chord guns on the choruses. Who knows whose directive Summers followed for the solo, but’s a shame he only stuck to his verse melody (though at least he got to stomp on the overdrive pedal), and that he was only allowed one pass through (he was thankfully allowed to repeat it live on that tour), though to whomever’s credit it fits the song perfectly. The bridge provides a nice break from the overtime-earning verse hooks, with Sting’s bass dropping way down, Andy’s rhythm track chunking out sixteenths on an F9/A chord, and his lead overdub picking out a nice melody comprised of artificial harmonics, executed 12 frets higher with the index and ring finger of the right hand, a technique few if any other guitarists were using, but Summers himself had occasionally employed since the first album.

“Wrapped Around Your Finger” is the most obvious representation of The Police’s ebbing reggae immersion on the album, on account of Summers’s periodic, dub-echoing A minor triad stabs from up high on the neck, and Copeland’s smooth yacht-rock groove, which is a more tranquil version of “Regatta De Blanc”’s, but with kick drum hits on the “and” of 2, and then 3, and a cross-stick snare hit on 4. It’s about as unusual for pop as a drummer could get, but even more effective. Sting again draws at once languidly soothing and edgy tones––and Jaco-esque natural harmonics––out of a fretless electric bass, but here, and for the only time, he has modified the accordatura, dropping the low E string a whole step down so he can reach the briny depths of D1 just as the choruses end.

Another brilliant lyric prevails, riding the coattails of another perfect set of hooks. Sting’s poetic genius lies in the fact that he is an expert at making the personal universal, and vice versa. Even as he is expressing the very depths of his then troubled soul (many of this album’s songs couldn’t help but address his recent transferal of marital affections and related tribulations, including this one), he never puffs his chest out with blatant egotistical assertions, but instead turns the tables with his trademark twists, and he is never self-referential enough to be off-putting. If any aspect of his lyrics is thus, it is his “pretentious” use of what is often unfamiliar vocabulary and literary references to the layman listener, again not referring to himself at all but to borrowed source material:

You consider me the young apprentice

Caught between the Scylla and Charybdis

Hypnotized by you if I should linger

Staring at the ring around your finger

I have only come here seeking knowledge

Things they would not teach me of in college

I can see the destiny you sold

Turn into a shining band of gold

I’ll be wrapped around your finger

Mephistopheles is not your name

I know what you’re up to just the same

I will listen hard to your tuition

You will see it come to its fruition

Devil and the deep blue sea behind me|

Vanish in the air, you’ll never find me|

I will turn your face to alabaster

When you find your servant is your master

Oh, you’ll be wrapped around my finger

The band’s long-standing, self-declared MO of “less is more” reaches its apogee on the astoundingly atmospheric “Tea in the Sahara,” which takes the textural bent of “Shadows in the Rain” to the next level of minimalistic subtlety. Only this time around, there was no relinquishing of any of Sting’s natural impulses, with the swinging jazz eighth and dominating bass figure and groove both foregone conclusions in the deep continuüm of this rich musical storytelling. A listener gets the sense that this song would sound just as complete if it were only the bass and vocal––i.e., Sting’s parts––on the recording; that’s how indispensable he made himself on this and every other Police track, and how crucial it was that his bandmates––or he himself?––found their proper places within the already self-sufficient soundscape he provided. They managed to do just that, with Copeland putting his verse kick hits on the lagging “and” of 2 (!), lining up perfectly with the last note of Sting’s bass phrases (a seemingly counterintuitive placement until one tries to imagine relocating it to any other beat), and Summers delicately volume-swelling in lush, attack-free chords in random places over the verse, and ethereally steady on the choruses, with such a soft, shimmering melodic touch as to seem aurally diaphanous, like windswept grains of sand catching the sunlight. And Sting, not satisfied with mapping out and owning the whole piece on bass and vocals, fills various remaining spaces with hauntingly reverbed, plaintive oboe keening (which he somehow manages to make sound like an exotic, middle-eastern equivalent), just in case one didn’t feel enough pathos from the music and lyrics alone:

My sisters and I

Have one wish before we die

And it may sound strange

As if our minds are deranged

Please don’t ask us why

Beneath the sheltering sky

We have this strange obsession

You have the means in your possession

Tea in the Sahara with you

The young man agreed

He would satisfy their need

So they danced for his pleasure

With a joy you could not measure

They would wait for him here

The same place every year

Beneath the sheltering sky

Across the desert he would fly

Tea in the Sahara with you

The sky turned to black

Would he ever come back?

They would climb a high dune

They would pray to the moon

But he’d never return

So the sisters would burn

As their eyes searched the land

With their cups still full of sand

The story told in this lyric is as fantastic as it is lachrymose. What a heartrending ending to what starts out as a wonderful tale, with Sting empathically projecting himself into one of the sisters’ first-person shoes, then disappearing into third person for the subsequent verses. There’s no Hollywood ending here, only the English Patient-like denouement rife with the indifferently inhospitable Saharan desert’s void-like symbolism and the female protagonists being fatally let down by the male counterparts they unjustifiably trusted. The dark turn of events at the end––the Sting surprise in this particular lyric––plunges the heretofore glinting story dagger into the listener’s left chest, then twists it around with the perfect musical accompaniment, and ends with the wistful sound of Sting’s falsetto’d G#4 on “you” fading out like wind over a distant dune.

It wouldn’t be such a travesty that the original vinyl pressing ends here if one wasn’t aware of the existence of “Murder ny Numbers” on the cassette version; “Tea in the Sahara” puts an otherwise fitting bow on Synchronicity as the final track, but just knowing that another Police classic is out there, and actually provides an even better ending to the album (and to the band itself), constitutes a cruel and unusual deprivation.

One of many incredible aspects about this other final cut is that it is an improvised first take, recorded just as Sting’s pre-existing lyric was expediently combined with Summers’s swinging, jazz-redolent chord changes. In that light, it’s easy to get awed and simultaneously confused by Copeland’s introductory groove–a crazy blues shuffle/reggae hybrid with the kick familiarly falling on 2 and 4 but hemiola (three beats symmetrically superimposed over two) cross-sticking on the snare––(not to mention all the killer fills he does later) until Sting comes in and sets things straight with the vocal, which chooses the macabre subject of mass murder as its focus:

Once that you’ve decided on a killing

First you make a stone of your heart

And if you find that your hands are sill willing

Then you can turn a murder into art

There really isn’t any need for bloodshed

You just do it with a little more finesse

If you can slip a tablet into someone’s coffee

Then it avoids an awful lot of mess

‘Cause it’s murder by numbers

One, two, three

It’s as easy to learn

As your ABC’s

Now if you have a taste for this experience

If you’re flushed with your very first success

Then you can try a twosome or a threesome

And find your conscience bothers you much less

Because murder is like anything you take to

It’s a habit-forming need for more and more

You can bump off every member of your family

And anybody else you find a bore

Now you can join the ranks of the illustrious

In history’s great dark hall of fame

All our greatest killers were industrious

At least the ones that we all know by name

But you can reach the top of your profession

If you become the leader of the land

For murder is the sport of the elected

And you don’t need to lift a finger of your hand

Sting seems to be writing from personal experience here, which is a shocking notion unless one analogously relates it to the “killing” he has made in his pop music career, starting with the few punters at their early London shows and building all the way up to this point where The Police were arguably the biggest band in the world, or at least big enough to consider getting out of the game before the law of diminishing returns exacted its inevitable punishment of entropy on the band’s unraveling synergy.

Ironically, or aptly depending on one’s perspective, The Police find themselves back where they started on “Murder by Numbers,” stripped down to the original power trio orchestration, no added synthesizer, saxophone, solos, or overdubbed vocal frills, just the well-orchestrated and reverbed band pushing the individual and group envelopes on a superlative underlying work. And though there are some common elements with their first-album selves––Copeland still feels compelled to give jazz (and ergo his bandmates) the middle finger, for instance––there’s no denying both the personal and musical maturation, and the physical, emotional, and creative mileage accrual belied by this recording, and the evidence of their impending dissolution in the form of their roadies’ cheekily desultory and anticlimactic piss-take applause from the control room after the shambolic end flourish.

**************

In contrast to their punk contemporaries, though interestingly enough like a few of their new wave cohorts, Sting, Stewart, and Andy were all on the older side of the typical pop star spectrum when they began their upward slog, and even more aged by the time they achieved their fame (Summers turned 40 while recording Synchronicity). They had developed proficiency on their instruments and as accessibly innovative songwriters, and had accrued real-life experiences and mind-expanding self- and externally-sourced pedagogy that would inform the universal appeal of their imaginative work. And while many of their fellow artists thought only of their own struggles to escape poverty in their fame chasing, Sting and Andy were already fathers during or just after that first US tour respectively, with families depending on them for financial and emotional support (Stewart would later join his two cohorts in fatherhood between the penultimate and final albums). It’s one thing to let oneself down, but disappointing one’s dependent family lends an other-oriented urgency––and the non-compromising gumption––to fulfilling one’s professional ambitions.

Many of today’s pop stars are separated from reality and groomed from their all too early youths to fill a superficial, highly sexualized image, with talent development, proper education, and the capturing of relatable but still poignant normal life experiences taking a back seat to brand management and highest-possible-trajectory career development. Whereas Sting imaginatively rhapsodized about he and his fellow female cohorts waiting at great personal risk to drink tea in the desert with you, the new brand of pop star––predominantly female––blather the exhausted social-media-fueled, self-aggrandizing litany of love, heartbreak, and empowerment tropes (are our kids even reading books anymore?). Whatever else the lyrics might pertain to, they more often than not reveal a lack of real life experiences and education in their focus on baser concerns, pandering to today’s burgeoning, internet-addled, shallow sheeple masses.

Not to say that any of this is necessary a bad thing––it is what it is. But for those of us who dearly miss the timeless sophistication of earlier eras and are dog tired of being blamed and shamed for our current pop artists’ failure to produce anything sufficiently stimulating, having to resort to digging through the infinite ocean of content that now deluges us online to locate even ersatz facsimiles of erstwhile greatness, it is incredibly vexing. Discerning listeners have now become time travelers of sorts, having to mostly reach backwards––or crate-dig deep into the ever-rich but obscure underground––to find music of sufficient merit. Even still, the new pop music that almost measures up seems to lack something fundamental–perhaps sufficient conviction and depth–though one can’t blame them, considering the terrible shape the virtually nonexistent music industry is in, and the concomitant impossibility of more than a scant few artists being able to make a living within it.

Put any Police record on the turntable––perhaps the 40th anniversary edition of Synchronicity that was recently released––and it still sounds fresh, relatably sophisticated, and exciting. Even the most filler of their tracks have a distinctiveness and inventive vitality that transcends eras and limitations of genre, and makes today’s pop music feel insouciantly self-involved, heartless, base, and formulaically robotic by comparison (no ProTools, Autotune, click tracks, or rhythmic quantization here––just reel-to-reel tape and good human ears and meter). In a time of crisis like this, when our entertainments have been whittled down to escapist, perfection-straightjacketed opiates to appease the head-in-the-sand masses, this solitary pursuit has almost become an act of rebellion, just like The Police rebelled against whatever limitations they faced in their heyday striving, knowing without a doubt that what they left behind would somehow transcend themselves and affect pop culture for the better.

Simeon Flick is an award-winning music journalist and a decades-long contributor to the San Diego Troubadour, as well as a San Diego Music Award-nominated singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, classical guitarist (he holds a Bachelor of Music in Classical Guitar Performance degree from the University of Redlands), and home studio owner and operator. He lives in La Mesa with his wife Allison and their two cats, Louis Winthorpe III and Billy Ray Valentine, Capricorn.