Yesterday And Today

Summer in the City: Looking Back on the Lovin’ Spoonful

I love my baby by the lovin’ spoonful.

—“The Coffee Blues” by Mississippi John Hurt

It’s subjectively peculiar, not to mention a tad bit reassuring, how certain recordings manage to retain an aura of timelessness. Sonic paintings mysteriously devoid of a date stamp, even when the sentiments and emotions on display are over a half-century out of chronological step with the here and now. And boy howdy!—regardless of your personal memories—history has amply demonstrated how the period of 1965–67 was an insanely spectacular confluence of energies. It was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, after all.

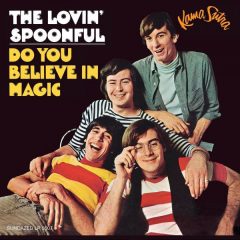

And, because popular music always reflects the culture of its time, within certain sectors of society (young, affluent, middle-class), 1965 projected a supremely sunny optimism, particularly on your local Top 40 station. And nowhere was this more apparent than in the Good Time Music of the Lovin’ Spoonful, and their jubilant salvo in August of ’65 “Do You Believe in Magic.” (Why doesn’t that title have a question mark?) It’s essentially a two-minute adrenaline-rush about the thrill of discovering how great it is to be alive—where dancing becomes a metaphor for grooving together with someone you dig down to the very soles of their shoes. It was a hell of a calling card to the general public, and after the single peaked at #9 on the Billboard Hot 100, it became the title track to their debut long-player in November.

Fifty-five years after its initial release, Do You Believe in Magic still holds together as a compelling collection of tunes from a quartet who had known one another barely a year. From the onset, the single most crucial element to the sound of the Lovin’ Spoonful is the songwriting and vocalizing of multi-instrumentalist John Sebastian. He revolutionized the use of the autoharp in popular music, and for his harmonica playing alone he deserves to be recognized as one of its premiere practitioners, right up there with Stevie Wonder, Sonny Terry, Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Norman Buffalo, Magic Dick, or anyone else you care to name. Sebastian’s jug band dustbowl musical roots were in perfect harmony with the Greenwich Village, passing-the-basket, folk music scene of the early ‘60s (he did, in fact, play bass on Bob Dylan’s electric breakout LP Bringing It All Back Home). It was in this emerging milieu that Sebastian bonded with guitarist Zal Yanovsky, fresh from a stint with Cass Elliot and Denny Doherty in the short-lived Mugwumps (see the Mamas & Papas “Creeque Alley” for the self-mythologizing backstory). Yanovsky projected a goofy irreverence that carried over to the way he phrased his licks. But he was never a showboater, and his playing always skillfully supported the song. His mastery of Chet Atkins, and the dirty blues licks of Chicago’s Chess Records, made him a natural exclamation point to Sebastian’s infectious melodies and playful earnestness. Yanovsky is the key ingredient as to why the Spoonful is an actual group, as opposed to a Sebastian solo project.

But just as vital to the collaboration is the rock ‘n’ roll bar band rhythm section of bassist Steve Boone and drummer/vocalist Joe Butler. Butler provides superb vocal backing to the Spoonful’s overall sound, but when he takes center stage to sing the occasional lead, the results can range from spotty (“You Baby”) to superb (“Full Measure”). However, I usually find myself eager to get back to one of Sebastian’s understated masterpieces.

The release schedule that was demanded of them by their label Kama Sutra was typical of the era—in other words, absolutely brutal. From the business side of the music industry, you’ve got to strike while the gold records are smoking hot. And over a period of twelve unbelievable months, that’s exactly what the Spoonful did, releasing four (that’s right, FOUR) LPs: Do You Believe In Magic, Daydream, the highly underrated soundtrack to the Woody Allen goof What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, and Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful. During that same period, they also notched up seven consecutive top ten singles, including a two-week stay at Number One in August of ’66 with the sublime perfection of “Summer in the City.”

By all indications the summer of ’66 should have been a time of celebration for the Spoonful, but after Boone and Yanovsky were arrested for possession of marijuana, the pair opted to finger their source in return for clemency (and to avoid deportation back to Canada for Yanovsky). When the news of their “treachery” as finks hit the streets, the group’s popularity plummeted amongst the guardians of hip.

But before it all went south the group distinguished themselves with a slew of hits, holding their own quite admirably in a world dominated by songs from the Brill Building, the British Invasion, the surf of Southern California, Motown, and the folk protest movement. They continued on their assent across their sophomore LP Daydream (released only four months after their debut), and the tricky exercise of coming up with compelling mood music for the spy movie spoof What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

After the superb Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful was released in November of ’66, the group tackled another soundtrack project in May of ’67 for Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now, before Yanovsky flew the coop in pursuit of a short-lived solo career (he released one LP in ’68: Alive and Well in Argentina). The talented yet miscast Jerry Yester of Association fame attempted to fill the breach on the Everything Playing LP, but the Spoonful’s magical dynamic was shattered, and by June of ’68 Sebastian departed for a high-profile solo career at Reprise Records. One last Spoonful LP (Revelation: Revolution ‘69) featuring Butler as lead vocalist, is a rather half-baked affair, offering complete justification of why lawsuits are initiated to protect the memory and integrity of a group’s body of work against charlatans cashing in on a successful brand (see also: the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, etc.).

Perhaps the most beautiful thing about Sundazed’s current reissue program of the first three Spoonful LPs (in glorious mono) is that the political brouhaha surrounding the group no longer needs to muddy the water when evaluating the quality of their work. The original quartet possessed an ethereal ‘X’ factor that refuses to date their best work. And for anyone who bought the stereo remasters that Buddha/BMG released on CD in 2003—you are highly encouraged to purchase these discs, particularly devotees of vinyl. Because, as awesome as stereo can be, it is an indisputable fact that most recordings before 1968–70 sound better in mono. And Sundazed has done a stellar job on remastering these essential LPs. Now, if they’d only get around to What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

And by the way, for the trainspotters out there, the lyrics to “Nashville Cats” are one of the few times that Sebastian got it factually wrong: “And the record man said every one was a yellow Sun record from Nashville.”

Sam Phillips’ classic record label was, of course, based out of Memphis. Pick it Zally.

Postscript: The original Lovin’ Spoonful did reunite in 1980 to perform “Do You Believe in Magic” for the Paul Simon film One Trick Pony. Zal Yanovsky eventually started his own restaurant in Toronto called Chez Piggy, with an adjacent bakery Pan Chancho. I was blessed with witnessing the very last reunion of the original quartet on March 6, 2000, when the Spoonful performed at their induction into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in New York at the Waldorf-Astoria. Nearly three years later, Yanovsky died of a heart attack. John Sebastian is still very active as a solo performer. And Joe Butler, Steve Boone, and Jerry Yester still perform occasionally under the moniker of “The Lovin’ Spoonful.”

From Ugly Things #40, Fall/Winter, 2015

On October 19, 1984, I had the opportunity to interview John Sebastian backstage at the Beverly Theatre in Los Angeles, California, where he was currently touring with Arlo Guthrie and David Bromberg. Sebastian was added to the bill to replace the late Steve Goodman (author of “City of New Orleans”), who had died a month before on September 20th at the age of 36 from leukemia. I ran into Sebastian backstage after his performance, introduced myself, and asked him if he would be willing to sit and talk for a bit on the record. To my astonishment he said yes, and twenty minutes later I walked out with my What’s Shakin’ LP autographed and a cassette of our encounter. Until now, this interview has remained unpublished.

Jon Kanis: So, how did you end up on this tour?

John Sebastian: Well, it came as a phone call. David [Bromberg] and I have worked frequently together. Arlo and I seem to meet up at every folk festival, but this was the first situation where I’ve gotten to play with them on a steady basis.

Have you ever gotten together and played more than one or two gigs with them before?

No, this is the first time.

This is your second night of the tour?

That’s right.

How did the first night go down in Arizona?

Very nicely.

Was it the same set you played this evening?

Basically, yes. All three of us are complete feel-it-as-it-comes kind of performers.

You improvise the set as it goes along?

That’s right.

I’ve noticed an absence of vinyl from you in the past few years.

God, it’s excruciating, isn’t it?

It’s quite excruciating for the fans who would like to hear from you time to time, and nobody’s giving you a chance to record.

Yeah, it is frustrating. But I think that the tide is turning a little bit now because I got a call from a man by the name of Ron Goldstein who used to run Island Records, and before that he was with Warner Bros. He is interested in putting together a label. And the audience that he’s after is the Baby Boomers—our contemporaries, or my contemporaries more than yours. And he came to me with several different ideas, including an album with various artists, with each one getting two cuts per person.

You mean like a What’s Shakin’ album?

Sort of like a What’s Shakin’ album. He had a lot of ideas, and then he came back and said “The best idea is that I make an album of you.” I said “Great!” So it looks like some time in the new year [1985] there may be a record out on Blue Highway. [Tar Beach was eventually released in 1992 on Shanachie Records.]

So they’ll front for the studio fees and hopefully give you some promotion?

Wouldn’t it be nice?

It would. Nothing is guaranteed these days, and if they don’t see the potential they’re not going to put any money behind it. But I feel that getting your name back out in front of people my age and younger is important. For me, the music from 1965 to ’67, the music that was on the radio then, there is nothing today that compares with that period of time.

It was a good period. I disagree with you to a certain extent. I’m excited by a lot of the things I hear. I think that the proportion of good music hasn’t changed that much. The industry has swollen incredibly, so that even though the percentages might be the same, the amount of bad stuff and the amount of good stuff has also swollen. I just think there are some marvelous things being done nowadays. Thomas Dolby is doing such interesting things with little chips and I like all this stuff that Sting is writing and Men at Work…

Do you think that some of the techno-pop artists are writing for more of a “sound” as opposed to writing good songs?

I think that there’s always room in pop music for a record that’s a good “sound,” and not necessarily a good song. I think that that hasn’t changed. I think that the Spoonful capitalized on that aspect as much as anybody.

That seems contradictory—it’s my observation that what came first with your sound was the meat of the song. I mean, “Coconut Grove—there is nothing to that production except a guitar and a vocal and another guitar underlining it. THAT sells the song, you don’t have some trendy-sounding synthesizer, and you don’t have a bunch of synth-pop drums. It’s the song that sells it. It’s an honest message.

Sure.

I just see a lack of good, honest songs in the market today, as opposed to sounds.

“Missing You.”

Well, I love John Waite.

It’s a good song.

It’s a great song. I, for one, think the Babys were one of the best bands to come out of the late ’70s. But very few people seem to agree with me, based on the amount of albums they sold.

Yeah, well I think there are good bands around. Like I say, it’s the proportion. There’s so much music nowadays. You really have to leaf through a lot of junk to get to anything worthwhile.

Well, I certainly agree with you on that. I’d like to hear a little bit about the background of the What’s Shakin’ album. Why did you record those four songs for Elektra [“Good Time Music,” “Almost Grown,” “Don’t Bank on It Baby,” and “Searchin”] and then move on to Kama Sutra Records?

Okay, it’s very simple. What happened was I had been a sideman for Elektra Records for four years by the time the Spoonful began. Paul Rothchild, who was a producer there and later produced the Doors, was sort of a moving force in putting together albums, concepts, and people. He made great combinations—get a good accompanist for a good singer who might not be a great guitar player and weave them together. I think that he was the connection to [Elektra president] Jac Holzman, who I eventually got to know myself. But Jac came to the Spoonful at a certain point and said “Look, you guys are going to be really good, in about nine months. So, here’s what I want to do. I’ll give you some studio experience. You go into the studio. I don’t want your ‘A’ tunes. Just give me four tunes of ‘cool stuff,’ but not your ‘A’ stuff. And I won’t release it. I’ll tell you right now what I’m going to do. I’m going to hold it. When the Spoonful has any degree of success, I’m going to put that album out. And, in return, I will buy amplifiers, which you guys need right now.” [laughs] It was true. And we were very glad at his candor, because he was very up front about exactly what he wanted to do. And we were flattered that somebody else believed in us at a time when no record company in New York would touch us.

Where did you come up with “Good Time Music?” It sounds rather pro-American, and rather anti-British Invasion.

Well, it wasn’t that it was anti-British. It was just that I saw so many American acts floundering for an idea at that point in time. Look, I love the Beatles. And I thought, “These guys are killing. They’re doing damage over here.” And there isn’t any reason why a hybrid American music can’t be equally exciting. Because what they were bringing over was an English-inflected American hybrid already. So, rather than try to wear Beatle haircuts and affect a Liverpudlian drawl to make records, why don’t we capitalize on our strong suit? And that’s where the song came from.

You introduced tonight’s set with the song “Welcome Back” which pushed your commercial stock up at a time when you hadn’t been heard on the radio for a while. You mentioned that it provided you with the funds to buy your house.

That was nice. It came at a moment when I think I couldn’t have gotten anybody to put any elaborate bets on me. [laughs] But it was very gratifying, and it brought in a younger audience than hadn’t been connected to me up to that point. Unfortunately, there really wasn’t much support at that time for the albums I was making. I made an album with the “Welcome Back” single on it, but it really is a secret album.

Well, it’s no secret to me, I love it. But it’s odd that you used the Stone Warblers for just the title cut and then all the studio musicians for the rest of the album.

Well, no, the Stone Warblers were the vocal group, and they sang on four or five numbers along with the fabulous Blintzes, who are credited on that album, too.

So why didn’t Warner Bros./Reprise Records do more to promote the album? They had a number one song and the single was one of the top songs of 1976?

That’s right, it was the second biggest record of the year. You’d have to ask somebody at the label, I couldn’t understand it. They were ready to let me go before that single, and I was very pleased with the fact that they were willing to say “Okay, this is not what’s fashionable right now. Alice Cooper is happening.” I said “Fine, let me go to a small company that would be really excited about having me.”And within the week of that conversation I had been working on this TV show theme and somebody over at Warner Bros. heard it and they went “Oh, wait a minute! We changed our minds. We think you’re marvelous.” [laughs] But I really don’t want to stress this in any interview, because the fact remains this is the business. And I know that it’s the business. I mean, it was frustrating, but I didn’t spend any time pouting about it. I wanted to aggressively get on to the next step, and it was too bad that the one that I had to take was so unproductive.

Well it definitely got your name out there again after the troubles you had with MGM releasing your live album unexpectedly…

Yeah, yeah.

And the Cheapo Cheapo album. The “She’s a Lady” single was pretty much the last surge you had on the charts up until the “Welcome Back” record and television show brought your name back into the public consciousness. So it had to be helpful in that sense.

Yes. But let’s go onto what I’m doing nowadays. Because over the last few years I’ve been doing about a hundred concerts a year, staying good and lean. And I’ve been doing some movie soundtracks. It was funny, because out of three movies that I did only one actually came out. and that was on television—the sequel to The Jerk that came out last spring [The Jerk, Too]. But the most fun that I’ve been having over the last few years has been with an animation firm called Nelvana. We did five or six of their productions.

Weren’t you advising them on the movements and how to shape guitar chords with the cartoon characters hands?

Yeah! You must have read a press release. Yes, that was a lot of fun. The earlier ones I really could work as a sort of musical director with them and get a lot going. After that, they started getting a lot of accounts from big toy conglomerates. And now I am the voice and composer for the last two Strawberry Shortcake cartoons, and the most recent Care Bears movie that’s coming out I imagine around Christmas. And I managed to use NRBQ, my favorite East Coast rock ‘n’ roll band.

They were playing behind you on a few dates back in ’82.

That’s right, in fact they’ve been playing with me frequently. In about a week I’m going to a jazz festival in Berlin to play with them.

I would love to see you play with them, especially on the Spoonful songs that you say need more “punch.”

Yes, the tunes that really need a band I’m so glad to be able to play somewhere. Because it’s funny, I have been an artist who has toured and survived not being able to play a lot of tunes that I wanted to because I really couldn’t support carrying a band.

Before we conclude I wanted to ask you about the Spoonful getting together for the One Trick Pony project and how the heck that came about? And why haven’t you gotten together with Zal and Steve and Joe and done a real reunion?

Okay. On a real basis, if you are going to join a band you’re going to be in the entertainment business. You have to be ready to do that. And Zally in particular has a very different life now. He owns and runs a beautiful restaurant in Ontario called Chez Piggy. It’s wonderful. Joe works in New York City, mostly as a foreman for these high-rent carpentry projects. Steven plays quite frequently, and in fact he and I still do concerts together. But on a real basis, you have to commit to a year or so of this kind of work, and I don’t see that the other guys really want to do that. And I don’t want to impose on their lives that much to say “Oh, you have to.” They wouldn’t pay any attention to me if I did. [laughs] I mean, thank God, I’ve got good friends. And the way the call came on One Trick Pony—we had been getting these offers, millions of bucks, and we’ll go out and charge a 25-dollar door and just gouge the shit out of them. And I just thought “Oh, this sounds so tawdry somehow.” And then Paul Simon called and said “Look, I need some guys who were a group way back when who look good and can still speak their own name and stand on a stage and you guys are elected.” I called up Zally and said “Look, here’s an offer: we play four or five tunes for Paul Simon’s movie and we get about three hundred dollars a day each.” Zally says “Hey, this sounds like us!” And so we did it.

Simple as that?

Uh huh.

Didn’t you have something like an hour’s worth of concert footage from that?

Yes, but they weren’t filming and they weren’t taping. They had a 24-track studio there and they didn’t turn the tape recorders on.

Oh, you’re kidding? They only recorded “Do You Believe In Magic?”

Yeah.

That’s it? Out of a whole hour long set?

Ten songs.

Well, that’s a missed opportunity, for sure. I know you need to get going, John. Thank you so much for your time.

Nice to meet you. Take care.

Besides performing over 1,000 gigs over the past 25 years, Jon Kanis is an award-winning author and Grammy-nominated producer who has contributed numerous cover stories and feature articles to the San Diego Troubadour since 2012. His interview with John Sebastian and critique of the Lovin’ Spoonful will appear in Volume Two of Encyclopedia Walking: Pop Culture & the Alchemy of Rock ‘n’ Roll, available in November 2020. For more information, email at jkanis@rocketmail.com.