Cover Story

Scribe of the Tribe: The Ballad of Paul Williams

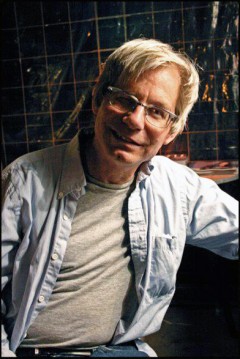

Paul Williams, 1948-2013. Photo by Dan Chusid.

Copy of Crawdaddy! from the late 1960s

Williams in the NYC Crawdaddy! office, 1967. Photo by David Hartwell.

Williams (bottom right) sitting next to Timothy Leary at the famous Bed-In with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 1969

Williams in New York City, 1973. Photo from the collection of Sachiko Kenanobu.

Williams, right, with Raymond Mungo, left, and Kurt Vonnegut, 1972

Paul Williams and Cindy Lee Berryhill, 1997

Cindy Lee, Paul, and Alexander, 2012. Photo by Denise Sullivan.

“Each man creates himself. Do not be afraid to love. The only sin is self-hatred. It is the act of self-negation. Words contain no awareness. They can only trigger awareness. It does no good to try to impress a man with some thought he can’t relate to. But if you can make him realize the obvious that might change his life.”

[from Das Energi by Paul Williams]

“Don’t ask me nothin’ about nothin’

I just might tell you the truth.”

[from “Outlaw Blues” by Bob Dylan]

In the mythic psyche of the vast American landscape known as the Wild West there are few things as celebrated as the archetype of the pioneer: staunch individualists who take risks where others fear to tread. The Hero With a Thousand Faces who often opens up new vistas of perception for the benefit and preparation of others. As revolutionary trailblazers basking in the adventure of the unknown, pioneers possess a vision of how to transform the world into something grander than what has come before. When we celebrate the innovations of the pioneer we simultaneously promote the evolution of the race by allowing our most progressive ideas to prevail. And call it being educated if you like (or simply being aware) but for any sort of evolution to occur a sense of our back story is crucial — because how can we know where we are going if we don’t understand where we’ve been? History is our moral compass (Joseph Campbell tagged it the Power of Myth) and it is through these stories that we know ourselves as a people.

Thankfully, every tribe throughout the ages has a learned wanderer who goes out into the world and reports his findings back to the village and for the past 20 years San Diego played host to one of the twentieth centuries’ most pioneering scribes: Mister Paul Steven Williams (who passed away on March 27, 2013 due to complications sustained from a traumatic head injury in 1995). As the author and editor of over 30 books covering a range of topics, from science fiction fandom to the underground rock and roll counterculture, Williams was also passionate about progressive politics and expressed his spiritual observations through the “practical philosophy” of his cosmic blank verse. He is considered by many to be the father of rock journalism with the creation of Crawdaddy! magazine, the first American publication to write about rock and roll as a serious art form (predating the similar enterprise of Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone by 18 months). As a 17-year-old freshman at Swarthmore College, Williams was an atypical wunderkind who was inspired by the grassroots broadsides being published for the science fiction and folk music communities and he took it upon himself to fire the first shot in declaring the good news that innovations in rock music had reached a new plateau. And he wanted to tell the world about it.

Williams: “The first issue of Crawdaddy! [The Magazine of Rock] was printed on Sunday, January 30, 1966, in a basement in Brooklyn, New York, on the mimeograph belonging to and operated by Ted White. I wrote everything in that first issue myself. The cover featured a quote from a new British group, the Fortunes, talking to a London music paper after returning from their first U.S. tour: ‘There is no musical paper scene out there like there is in England. The trades are strictly for the business side of music and the only things left are the fan magazines that mostly do the ‘what color sock my idol wears’ bit.’

“My vision of the magazine [was to provide a forum] where young people could share with each other the powerful, life-changing experiences that we were having listening to new music in the mid-1960s. Since I didn’t have a way to get my new magazine into the hands of thousands of young music lovers immediately, my short-term focus was to get the attention of the radio station and record company people to whom I planned to mail complimentary copies of the first issue. In truth, I really was interested in whether a record would be a “hit” or not and if that was something I could predict or influence. I had been fascinated by Top 40 artists since I was 10 years old, impatiently bicycling to the record store every week on the day the local radio station’s new Top 40 handout sheet would be available. (Where’s ‘Charlie Brown’ by the Coasters this week?)

“We printed 500 copies of that first issue. The first copies were mailed from New York (five cents apiece for first-class mail then) on Monday before I hitchhiked back to Swarthmore, carrying the rest of the magazines, many of which I soon mailed to music business names from Billboard magazine’s annual directory. The total budget for the first issue, including postage, mimeograph stencils, paper, ink, 15-cent subway fares, peanut butter sandwiches, and the one album I bought and reviewed (Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence) was less than 40 dollars.

“The most noteworthy response to the new magazine came later in the week when Paul Simon called me at the freshman dormitory to say that my review was the first “intelligent” thing that had been written about their music. Perhaps he also gently corrected my false idea that Garfunkel was the guitar player of the duo (I’d figured he had to be, since Simon wrote the songs and sang the leads). I was invited to meet them on my next trip to New York. They introduced me to their manager and brought me along to a concert and a radio interview.”

Beware means be aware.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 19, 1948 it seemed inevitable that Williams would come to the West Coast as he later claimed to have “California in his blood. My dad [Robert] is from Palo Alto. He met my Brooklyn mom [Janet] at Los Alamos, working on the atomic bomb [i.e., the Manhattan Project].” Small wonder that with a nuclear physicist for a father it would be natural for Williams to become passionate about the ideas contained in the literary realm of science fiction. Not to mention the explosive fissions occurring in the world of rock and roll.

Williams: “The reason why I started Crawdaddy! is because it had never been done before. I was 17 and heavily influenced and inspired by the two scenes that I’d hung out in during my teen years: science fiction fandom and the Cambridge, Massachusetts folk music thing. Science fiction fans are readers who get involved in a conversation with each other and soon become more interested in the conversation than in the SF stories that brought them together in the first place. They [we] invented the word fanzine. I used to publish a science fiction fanzine when I was 14 and 15, so I knew that the freedom of the press belongs to anyone who owns a typewriter and can cut a stencil and has access to a mimeograph.

“I read an article by Jim Warren about how to become a magazine publisher. He got across to me the idea that what you needed was to find an audience that had a keen interest in something that was not yet being covered in a professional magazine and go forth and fill the niche.

“So I discovered girls and Dave Van Ronk and Howlin’ Wolf and didn’t publish any fanzines for awhile. I heard Skip James perform at Club 47. Then the Rolling Stones converted me to rock and roll and I was off to my freshman year in college and I started thinking that if there were folk music magazines, why not a rock and roll magazine? I thought I’d call it Crawdaddy! after the club in London where the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds got their start.”

After publishing a few issues of Crawdaddy! Williams dropped out of college, moved to the Philadelphia suburbs, went back to Boston for awhile and eventually landed in Greenwich Village. Williams: “Within a month of arriving in New York, Crawdaddy! was written up in Howard Smith’s “Scene” column in the Village Voice and the next thing I knew I was at a meeting of Interesting People and Richard Alpert (aka Ram Dass) was telling us about the Human Be-In that had just been held in San Francisco and we were there to talk about bringing it out east. Four of us of like mind detached ourselves from the rest of the conversation and went ahead and organized the first New York Be-In for Easter Sunday, 1967 in Central Park. It was really great. We believed in no agenda, no explanation, no entertainment — just let people show up. And they did. It was the first time that I saw really serious energy surfacing.

“There was a sense that something was happening and it just seemed to feed on itself. I saw the Doors at Ondine in New York and Buffalo Springfield at the Whisky before their first album came out and the Airplane and the Dead and Janis at the psychedelic ballrooms in San Francisco. I first smoked dope with a guy from a group called the Lost in Cambridge in September of ’66 but I didn’t get off and didn’t try it again until I was interviewing Brian Wilson in his meditation tent in his living room in Bel Air a couple of days before Christmas that same year.” During that visit to Los Angeles Williams wrote about the tracks that Wilson was currently working on, being one of the first people to hear the songs that he and Van Dyke Parks had created under the working title of Dumb Angel, later to be called SMiLE. When Wilson shelved the entire project the myth around SMiLE grew to immense proportions, in part by Williams’ excitations about the material in the pages of Crawdaddy! No one knew at the time that it would be another four decades before those legendary tracks would be officially released.

By the end of 1968, after three years of publishing Crawdaddy! (where the readership jumped from its initial 500 copies per issue to a staggering 25,000) Williams decided to walk away from the enterprise — and say goodbye to NYC. “I just wanted to go on to the next thing,” he said, “which turned out to be a cabin in the woods in Mendocino.”

After handing the reigns of the magazine off to some friends Williams was still interested in doing freelance assignments. In early 1969 Jann Wenner asked him to interview Timothy Leary for Rolling Stone. One thing led to another and the next thing he knew he was a charter member for a day in the Plastic Ono Band, clapping and singing along on their debut single “Give Peace a Chance.”

Williams: “Tim and I got to know each other a little and after a few months he said he was going to run for governor of California and would I like to be his campaign manager? I held the post for about ten days. We found out that John Lennon and Yoko Ono were planning to do a bed-in for peace in Montreal, so of course we had to go to Montreal.

“We had a fabulous visit. Tim explained his gubernatorial platform (something about a marijuana tax) and said that he and his wife Rosemary were really running together as a couple and that he/they tremendously admired John and Yoko’s revolutionary expression of coupleness and their campaign slogan was “Come Together, Join the Party!” And would John please consider writing a campaign song?

“The next day [June 1, 1969] John and Yoko got us and the Hare Krishnas and Tommy Smothers together in a small hotel room converted into a recording studio [Room 1742 at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel] and we all sang “Give Peace A Chance.” You can see me swaying and clapping in the video, which was shot more or less over my shoulder. Then it was time to go.”

Participating in the energy flow is the only satisfaction there is in life.

Eventually, a greatest hits anthology of PW’s early Crawdaddy! work was compiled under the cover of Outlaw Blues: A Book of Rock Music in 1969. It was the first in a long line of tomes. If it seemed like Williams had dropped out of conventional social circles by 1970 it was because he had, as reflected in the publication of 1972’s Time Between. “The theme of the book is transition,” writes Williams. “The sense of being caught between the old world and the new. I wrote it in a burst of energy between December 27, 1969 and February 19, 1970. It starts by describing the goings-on around me (mostly sex and LSD, enthusiasm and conflict) in the commune I was then living at in Mendocino, northern California. It continues through a disjointed cross-country rap on [Robert A. Heinlin’s] Stranger in a Strange Land, Charlie Manson, Mick Jagger, breaking free of the old world, love between men, moving to Canada — and settles into a visit and series of adventures in another commune, the Total Loss Farm in Vermont. The book ends with the author’s awareness of and suggested cure for his own schizophrenia [combined with final comments on the messiah myth, another recurring theme].” It’s somehow telling that Williams refers to himself in the third person as comment on his “schizophrenia.” If Time Between chronicles the period of Williams having a breakdown, his next book, Das Energi, would prove to be the breakthrough of his publishing career.

When your space is clear the whole universe functions at its best.

Williams: “When I was living on an island commune in Canada in 1970, I found myself writing this strange book called Das Energi, a few lines a day, feeling very guilty because I should have been working in the garden or otherwise making myself useful. Das Energi was turned down by lots of publishers and finally Elektra Records decided to put it out, their first and only book, in 1973. It turned into a word-of-mouth bestseller and it’s been through 23 printings in the United States and has sold at least as many copies as all my other books together.”

Despite the feel-good/new-age vibes present in Das Energi, Remember Your Essence, and his other works of philosophy, Williams could also be quite confrontational with his prose (he did, after all, participate in the march on the Pentagon in 1967). Hardly a doe-eyed flower child, he retained a righteous indignation throughout his life about the social imbalances inherent in the political status quo. He was frequently insistent that “the People” get off of their complacent, apathetic asses and correct the injustices of the world. In 1995 he railed in print against the “American bankers and stockbrokers [and their political and media puppets] and the sucker game they’re running. I want to talk about it except I honestly feel that no one wants to hear it, which is depressing. Why are we nostalgic for a time when people tried to find out the truth and do something about what was going on, but we resist following the same course now, this decade, this present moment? We’re moral idiots and it’s going to cost us.”

The 1970s found Williams’ book projects moving further away from the world of rock and roll and more in alignment with his spiritual and political interests. Before the seventies were over he wrote five more chronicles of his emerging consciousness: Pushing Upward (1973), Apple Bay or Life on the Planet (1976), Right to Pass and Other True Stories (1977), Coming (1977), and Heart of Gold (written 1978, published 1991). In 1979 he merged his philosophical explorations with his love for music in Dylan — What Happened?, where he pondered the implications of Bob Dylan’s then-recent conversion to born-again Christianity.

A prolific run of titles continued into the ’80s with The Book of Houses (1980) (co-authored with Robert Cole), The International Bill of Human Rights and Common Sense (1982), Waking Up Together (1984), Remember Your Essence (1987), and The Map or Rediscovering Rock and Roll (A Journey) (1988). The Map is perhaps the most significant of these titles because it documented Williams’ return into the world of music after a 15-year lack of interest.

The Map reads like the journal of someone who fell out of love with their first girlfriend and then 15 years after breaking up with her discovered after a long Homeric odyssey that not only were you still in love with her but now brazened by Life (experiences that took him from the ages of 25 to 40) he actually loves her even more. Such was the muse of music for Williams and it was this rekindled affection that inspired him to undertake the deepest project of his career, his three-volume series of Bob Dylan’s recorded output chronicled in Performing Artist.

Performing Artist is in many ways the crowning achievement of Williams career. It is certainly the most sustained meditation that he undertook in all of his writing projects. In Performing Artist Williams becomes the virtual fly on the wall and all he has to base his perceptions upon are the same tapes that any other Dylan collector might possess. But somehow he conveys to the reader startling insights into Dylan’s process, insisting that not only is Bob Dylan rightly considered the William Shakespeare of our time as a writer, but also that his abilities as a performer are of an equal caliber.

If a picture is worth a thousand words then these sound paintings that Williams draws from are a museum’s worth of impressions to build a cathedral in your consciousness, raising your awareness to unforeseen heights. This is what the best writers and artists do through their word and picture symbols. Bob Dylan is a master at it. And Paul Williams is a master at chronicling the process of the master at work.

Volume One of Bob Dylan: Performing Artist covered the years of 1960 through 1973 and was published in 1990. Volume Two, covering the middle years of 1974 through 1986, quickly followed in 1992. In 1993 Williams undertook the impossible task of personally choosing his favorite rock and roll singles of all time and writing a brief essay about each record. The result was the wonderfully eclectic offering Rock and Roll: The 100 Best Singles, including a forward by his future wife-to-be Cindy Lee Berryhill.

Energy flows through all things; it rests in none of them.

In addition to the spiritual philosophy of Das Energi and all of his work regarding how rock and roll music made his heart sing and spirit soar, there is, of course, the long shadow cast across Williams’ entire career by his first true love: science fiction. As a teenager he was entranced by the work of writer Theodore Sturgeon and would later serve as the authoritative last word on Sturgeon’s work by editing, compiling, and commenting in The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon. As Sturgeon’s literary overseer it was a function that Williams would also undertake for another of science fiction’s most acclaimed writers: Philip K. Dick.

Williams became aware of Dick’s writing in 1967 after being turned on by fellow enthusiast Art Spiegelman. “Phil and I met at a science fiction convention in 1968 and were close friends until his death in 1982, the same year that Blade Runner came out based on his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? In 1975 Williams wrote a profile on Dick for Rolling Stone magazine, eventually expanding the manuscript in 1986 to book length for Only Apparently Real: The World of Philip K. Dick, a fantastic document that shows how the two writers related to each other as friends. It offers up a rich background on Dick’s career and focuses on the multiple theories as to why Dick’s San Rafael, California house was burglarized on November 17, 1971 [take your pick: it was either the extreme right or the extreme left — the local police — rival neighbor gangs or the Black Panthers or…]. The two writers enjoyed an easy dialog with each and the affection between them is palpable. When Dick died on March 2, 1982 Williams became Dick’s literary executor, getting several previously unpublished manuscripts placed with printers and editing and publishing a newsletter for The Phllip K. Dick Society.

The ringing of the mindfulness bell.

If it’s true that writers require large amounts of solitude to perform and perfect their craft then, conversely, there are also the social dictates of business meetings, interviews, and travel that require being out in the world. Williams found a stable foundation for this dichotomy of demands in the three-act scenario of his marriages, where he performed the classic roles of husband, father, provider, and friend. In 1972 he married Sachiko Kanenobu, a Japanese singer-songwriter with whom he raised two sons, Taiyo and Kenta (causing him to relocate for a second time to New York City). In the 1980s he moved to Glen Ellen, California and married artist Donna Nassar (a chiropractor/healer by profession), where Williams served as stepfather to her two children Eric and Isabelle (and also served for ten years as a volunteer fire fighter). Sometime in 1992 he fell in love with singer-songwriter-musician Cindy Lee Berryhill, which led to his relocation to Encinitas in 1993. After the two wed in July of 1997, their union produced a son Alexander Berryhill-Williams in 2001.

His relocation to Southern California coincided with the decision to revive the Crawdaddy! imprint as Williams once again began self-publishing a quarterly newsletter in the winter of 1993, in many ways picking up where he left off in 1968. The newsletter was a success and introduced Williams’ writing to a new generation of music fans who weren’t around for the first incarnation. Everything was flowing in his personal and professional career until Saturday, April 15, 1995 — when everything came to an abrupt halt.

Cindy Lee Berryhill: “It was tax day. Because he was riding his bicycle to the post office to drop off the taxes and he was on his way back and there’s this treacherous hill that you go down and if you want to get up the other one you go down the first one fast. So he was going too fast and he didn’t have a helmet on.

“At that time Garage Orchestra was out [Berryhill’s fourth album from 1994]. I’d been touring for that album and was just starting to put together some songs for the next one and when Paul’s accident happened it kind of exploded whatever I was gonna do. I became a caregiver for like three months. But he did remarkably well and had a miraculous recovery. And because he was such a genius already, losing a few brain cells didn’t seem to alter things too much. In fact, a mere three months or so after his accident he had a book tour to do in Europe and I accompanied him on the book tour and actually played a few songs on his tour: I was his opening act sometimes. It was that kind of thing. He was mostly talking about Bob Dylan.

“My focus was really on him that year and then I recorded the next album Straight Outta Marysville. A song like “Unknown Master Painter,” I wrote that in the couple of weeks of Paul’s return from the hospital and I had this overwhelming feeling at the time of wanting to get in the car and drive east as far and fast as I could and just escape. But I’m not that kind of person, so I’m not going to do that. But I wrote the song and it was a way for me to escape.”

Williams did indeed manage to make a miraculous recovery, as evidenced by the remarkable output of projects that he completed during the last half of the ’90s. In addition to continuing with the responsibilities of writing and publishing Crawdaddy! he also published seven more titles between 1995 and 2004: Fear of Truth (Energi Inscriptions) (1995), Bob Dylan: Watching the River Flow (1996), Neil Young: Love to Burn (1997), Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys — How Deep Is the Ocean (1997), How to Become Fabulously Wealthy at Home in 30 Minutes (1999), The Twentieth Century’s Greatest Hits (2000), and Bob Dylan: Performing Artist Volume Three: Mind Out of Time, 1987-2000 (2004).

However, by 2009 Williams was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, the early onset caused by his accident. Berryhill documents the tragic, grueling process of watching her husband drift away in stages on Beloved Stranger, the name of her blog site and the title of her extremely riveting sixth album from 2007. Berryhill eventually created a website (paulwilliams.com) to promote awareness of her husband’s work and to solicit financial assistance for the enormous medical bills.

A retrospective curated by Johan Kugelberg titled Paul Williams: A Science Fiction and Rock and Roll Trufan at the Boo-Horray gallery in New York City was held on March 24th just three days before Williams left his body, giving up the ghost of a compromised vehicle that his tremendous spirit had housed for over six decades.

Berryhill: “Johan proposed the idea three weeks before it happened. He wanted it to happen quickly and for it to be a celebration of Paul and his work. At that point Paul had started hospice, so it was a thoughtful thing to do.

“I was able to share with Paul over the phone how beautiful his show was. There were so many writers that were there and everyone was saying that they couldn’t believe how much that he’d written… and that was only a fraction of his stuff. The other news I had for Paul was that two very impressive libraries were interested in taking his books and papers, thanks to Johan.

“When you read an essay that he wrote about a song he said these things that you were thinking and that you felt about the music but you could never articulate it the way that he could. As a musician you just thought, ‘I gotta write something that good! I gotta write a song as good as that.’ Because he could actually come up with the words to talk about ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ and I’d think that if I could say it that’s exactly what I’d say. He was like the perfect listener for us musicians. He really listened. And as somebody who got to live with him if I tried out a new song on him he was very much as he was as a writer. He either really liked it: “That’s powerful!” or he wouldn’t say anything. [laughs] Or he would say, ‘I haven’t listened to it enough to know. I don’t know if I have an opinion about it.’”

Sort of from the If You Don’t Have Anything Nice to Say school?

“Yeah, definitely. He said to me, ‘Why would I waste my time?’ It needed to be music or a piece of writing that really talks to him.

“But you know, ultimately, what he writes about is transcendence.”

A memorial (Celebration of Life for Paul Williams) was conducted at Pilgrim United Church of Christ in Carlsbad on April 7. A second memorial took place in San Francisco on April 13.

Engaging in a Form of Prayer: Remembering Paul Williams

It has been an incredible whirlwind these past few weeks, meditating on Paul Williams’s life and legacy. I am humbled by the task of writing his story and am left feeling such a range of emotions: giddy one minute, sad the next. But when I pause and take a deep breath what I mostly feel about the guy is triumphant about what he managed to create in his short time on this planet. Another emotion that I could add to my palate is frustration, because shy of a 10,000 page multi-volume compendium there is just no way to portray the full range of his literary gifts.

I believe that Paul thought this trip was largely about communication — in order to create communion. One of the thoughts that he committed to paper, and made an example of his life, was that: “The only way to enjoy the show, to enjoy life, is to be a participant. Perhaps it’s the people who think they’re spectators who spread the idea that all pleasure must be paid for. Don’t pay for anything — life is free.” Not exactly what you would call the thinking of a free-market capitalist…

Part of the beauty of Paul’s words are that they offer a window into a period of personal and collective history as well as a glimpse into the timeless possibilities. His words are an evocation and an invitation of how to see, think, and BE, suggesting that if you’re willing to take action and responsibility for your personal vision that you can change yourself and, by doing so, subsequently change the world. The best art is inspirational and suggests that by being bold and courageous you can do anything. So, (I can hear Paul saying) get cracking, kid!

I also believe in the law of magnetism, which perhaps accounts for how I found myself on June 9, 1986 on Jerry Weddle’s couch in University Heights talking about the great, lost Beach Boys album SMiLE with Paul. I came prepared to our get together by bringing a bootleg copy of SMiLE on cassette (unbeknownst to me he hadn’t heard the material since 1966). In appreciation for the tape he whipped out a copy of Dylan — What Happened? — signed it and handed it to me. I was only 21 but already an appreciator of Paul’s work and felt that his writing regarding the mysterious power and spiritual sway of rock and roll is as substantive and significant as the very sounds that inspired him to write in the first place. You could look Paul in the eye and know that you had a confidante who held a paradigm-shifting secret that he was dying to share with the world. He was endowed with a compassionate fervor that wanted to hip everyone to the awareness that music could expand your consciousness and had the power to heal your soul and affirm the beauty of existence. In his essay on the Rolling Stones single “The Last Time” he makes it clear that music wasn’t just a pastime or background noise, that it was no less than Existence Itself: “We’re talking holy noise here, sacred writ,” adding that a great 45-rpm record could contain “sex and death and humor and an attitude and a great beat and guitar piano vocal orchestral rock and roll music to die for.” Jeez, no wonder I loved the guy…

The day I met Paul I happened to have an extra ticket for the inaugural San Diego date of a 41-city North American tour by Bob Dylan, who was touring at the time with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Paul had an extra ticket for a show in Berkeley a few days later so we swapped. I had never seen Bob Dylan before and when the week was over I experienced four spectacular shows with Paul in San Diego, Berkeley, and Costa Mesa. Over the next decade I would see Dylan another 30 times and the frequent post-concert ritual would find many of us sharing notes about which songs were played and how well the evening came off. Most times I witnessed Paul in what seemed to be a state of ecstasy after seeing Dylan play and over time I came to share his conviction that beyond his obvious genius as a writer that Bob Dylan was also one of the greatest singers in the history of popular music.

Paul was a spiritual brother in every sense of the word. While it was music, music, music that brought us together I also learned a great deal about Zen philosophy, astrology, and the Book of Changes, the I Ching from him. He was the first person I ever saw throw a hexagram when grappling with the uncertainty about how to handle a particular problem. He was an old-school hippie, a wise magician, a science-fiction geek with nerd glasses and he knew how to use words as a divination tool. You heard music differently after Paul’s sensibilities had zig-zagged through your skull; astonishing pictures could emerge from the previously unconnected dots that his prose drew together, turning your mirror maze of a mind into a cultural playground as profound as the discovery of fire or the invention of the wheel.

Once in awhile I would get a postcard from Paul when he was out in the world traveling. One card dated March 13, 1995, sent from Prague reads: “Totally in love with this city — five days not enough! Wallet stolen but I don’t care — Dylan reinventing self by putting down his guitar — he always surprises! Love, Paul”

Thinking about his passion always makes me smile and it was a privilege to witness his process. I have a slew of happy memories from when he was immersed in the writing and research of The Map or Rock and Roll: The 100 Best Singles. I couldn’t help but being just a little bit pleased by being listed in the acknowledgements for helping him out with the Bob Dylan: Performing Artist series. There were other cool times as well having “postage parties” where we mailed out issues of Crawdaddy! to the subscribers in ’93, ’94, and ’95 — listening to records or cassettes, swapping stories, arguing over the relative merits of this LP or that artist and always while passing around the peace pipe.

We were hanging out together in July of ’88 when we heard the news that Nico had died from a freak bike accident in Ibiza. Paul got extremely upset by the news and slammed his fists into his knees crying out “No! No!” and fired off a few choice expletives to express his anger and sadness. Well, that visceral response was exactly how I felt when I received the news around Paul’s own bicycle accident in April 1995 and after visiting him in the hospital a couple of weeks later with Cindy Lee I was stunned by how quickly things can change on a dime. I am grateful for the generosity of Paul’s spirit and that I was privileged to bear witness to all the beautiful energy that he poured into the world. He is definitely missed and yet his ideas will be perpetually with us and I look forward to meeting up again in the next lifetime. Thanks for making a difference man.

– Jon Kanis